- Visit the Imagineering Graveyard

- Now Sailing: "Skipper Stories" - Tales from the Jungle Cruise

- Coming Soon: The biography of Disney animator Jack Hannah

- Coming Soon: A Haunted Mansion anthology

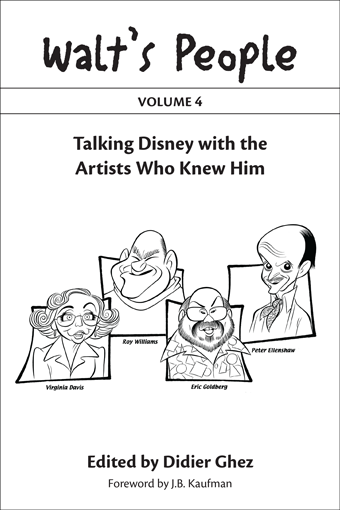

Walt's People: Volume 4

Talking Disney with the Artists Who Knew Him

by Didier Ghez | Release Date: September 12, 2015 | Availability: Print, Kindle

Disney History from the Source

The Walt's People series is an oral history of all things Disney, as told by the artists, animators, designers, engineers, and executives who made it happen, from the 1920s through the present.

Walt's People: Volume 4 features appearances by Virgina Davis McGhee, Dick Huemer, Joe Grant, Peter Ellenshaw, John Hench, Marc Davis, Lou Debney, Stan Green, Leo Salkin, Dale Oliver, Dick Moores, Roger Armstrong, Roy Williams, Brian Sibley, Ted Berman, Floyd Norman, and Eric Goldberg.

Among the hundreds of stories in this volume:

- DICK HUEMER shares highlights from his five decades as an animator, as well as in-depth remembrances of working with Walt and many of Disney's top animators and storymen.

- PETER ELLENSHAW draws the dots of his Disney career as an Academy Award-winning artist and matte painter for 34 Disney films.

- ROY WILLIAMS looks back on his life spent at Disney, including the time he mistook Walt for a traffic boy, and how that incident led to their long friendship.

- JOE GRANT pulls no punches, and spares no feelings, in a wide-ranging post-mortem of his many years with Disney.

The entertaining, informative stories in every volume of Walt's People will please both Disney scholars and eager fans alike.

Table of Contents

Foreword

Introduction

Virginia Davis McGhee by Russell Merritt and J.B. Kaufman

Dick Huemer by Grim Natwick

Dick Huemer by Joe Adamson

Dick Huemer by Brian Sibley

Dick Huemer: Huemeresque

Joe Grant by Michael Barrier

Peter Ellenshaw by Jim Korkis

John Hench by Armand Eisen

Marc Davis by Armand Eisen

Lou Debney by Dave Smith

Stan Green by Charles Solomon

Leo Salkin by Charles Solomon

Dale Oliver by Christian Renaut

Dick Moores by Alberto Becattini

Roger Armstrong by Alberto Becattini

Roy Williams by Don Peri

Brian Sibley by Didier Ghez

Ted Berman by Christian Renaut

Floyd Norman (columns)

Floyd Norman by Celbi Vagner Pegoraro

Eric Goldberg by Christian Ziebarth

Further Reading

About the Authors

Foreword

History is a tricky business. From the vantage point of a later time, we seek to understand the continuity of past events so that we can understand their significance. That distance in time is critical: if we’re lucky, it affords us a clearer perspective on the meaning of historical events—without utterly obscuring the events themselves.

Some kinds of history are more elusive than others, and Disney history is particularly difficult to pin down. The Walt Disney Studio, under Walt Disney, was an artistic miracle: There was an explosion of creative talent such as few of us living today have ever seen or ever will see. In these early years of the 21st century when our popular culture has been so radically dumbed down, the achievements of the Disney studio seem doubly remarkable. Thankfully, the artistic legacy of this exceptional man and the equally exceptional array of talent he assembled was captured on film and has been preserved. But along with that legacy, we have the responsibility of preserving the history behind Walt Disney’s achievements—a history crowded with events, inspiration, technological innovation, and circumstance, not to mention a host of artistic egos which were yoked together but occasionally at odds with one another. How can we possibly organize all the remnants of that turbulent time into a continuity that makes sense and that captures the lasting significance of Walt Disney and his work?

Interviews with Disney veterans are an indispensable tool in that process. In the eyewitness accounts of the artists who worked on the films, Disney history comes alive, sometimes with electric clarity. As Michael Barrier has written in an earlier volume in this series, most of the Disney artists knew they were participating in something significant, and the day-to-day events of their working lives were burned into their memories. Those recollections come spilling out again with vivid freshness in their interviews, sometimes recorded many decades after the fact.

Paradoxically, the very immediacy that makes Disney interviews so precious can also work against them. Walt Disney employed a wildly diverse group of artists over the years, and no two of them remembered the same events in quite the same way. Some of them, in the intervening decades, recast their memories in a more self-serving light or nursed grudges that awaited only a listening ear. Others were born raconteurs who would never allow historical fact to stand in the way of a good anecdote. Disney interviews, like any interviews, must be handled with care; they can provide penetrating insights if the reader takes into account the interviewee’s quirks, disposition, and circumstances. This is the genius of Didier Ghez’s series of anthologies: each interview in these pages, precious though it is, is only one facet. It’s in the accretion of those facets that we really begin to understand the Disney phenomenon. If one Ward Kimball interview is a good thing, two Kimball interviews back-to-back, as in Volume 2, are surely even better, and the balancing influences of Frank Thomas and Eric Larson in the same volume make them better still. In the cumulative memory of these shared experiences, we gain a fuller understanding of the Disney studio during its peak years.

At the heart of the studio, of course, was Walt Disney himself. In my own experience—and I’m sure most of the interviewers represented in these volumes can tell a similar story—I’ve spoken with former Disney artists who loved Walt with an undying devotion, others who despised him with an equal passion, and still others who occupied any number of gradations in between. (And it’s worth noting that even his most venomous detractors, in unguarded moments, admitted a grudging admiration for him.) From this varied combination of accounts has emerged a three-dimensional portrait of a human being, subject to normal human virtues and flaws, but ultimately an extraordinary man who accomplished extraordinary things. The Walt’s People series offers us a similar revelation. In these pages, a vital piece of our cultural history comes to life, and we come away with a fuller understanding of Walt, Walt’s people, and the indelible art they created together.

Introduction

I like to write Walt’s People introductions while traveling, be it on business or on vacation. This time I am on vacation, on the small Greek island of Amorgos. What makes this a special occasion, though, is that this trip marks an important break in my life: After having worked 10 years for The Walt Disney Company, I have decided to move to Warner Bros. No worries, though. I will carry on with Walt’s People during my free time; this project was never linked to my professional life. It was and remains a “labor of love”.

The move to Warner, however, becomes meaningful when it makes me seriously think about launching a new book series, in parallel to Walt’s People, called Bugs’ Buddies (my thanks to Steve Schneider for suggesting this title), which would focus on Warner animation artists. Will I find an editor for this project as passionate about Warner animation as I am about Disney? Or will I end up launching this project myself someday? We will see.

What is certain is that this project is also long overdue and would serve as a crucial complement to Walt’s People. We already saw in past volumes that understanding the creative life of Disney artists like Grim Natwick, Friz Freleng, or Frank Tashlin is close to impossible without taking into account their experiences at other studios. In addition, the links between Warner’s animation history and Disney are many and are often fascinating, from the creation of what would become the Warner animation studio by Walt’s pre-Mickey Mouse artists, Rudy Ising and Hugh Harman, to the brief stint of Chuck Jones at Disney in 1953, and through the various references to Disney within Warner cartoons, like the caricature of Ward Kimball in Hiawatha’s Rabbit Hunt (1941).

Once again, time will tell if I manage to find an enthusiastic editor for Bugs’ Buddies. Regardless of what happens, however, the momentum is there, as more and more serious animation historians have recently caught a surprising new wind. Something extremely exciting is going on. CartoonBrew’s editor Jerry Beck summed it up:

There is a quiet revolution happening in the animation community, and it’s all thanks to the internet. With the explosion of blogs in the past year, a wide range of difficult-to-find historical material is becoming publicly available for the first time. The availability of this material, which includes artwork, documents, films, and analysis, doesn’t only benefit historians; it also benefits artists in all parts of the world, who now have open access to examples of quality animation.

A few years ago Michael Barrier, the godfather of animation history and my main influence when starting Walt’s People, launched his blog; just over a year ago Clay Kaytis started Animation Podcast, a site solely dedicated to great interviews with animation artists; a few months ago, Animation Blast’s editor, Amid Amidi, created Cartoon Modern, a blog that complements his book of the same title and offers extremely in-depth insights into the lives of many key animation artists, quite a few of whom worked for Disney.

And then things went wild! Animator Jenny Lerew posted more amazing Freddy Moore artwork (from the collection of James Walker) than I had seen in years (and that screams to be collected in book form), along with rare “animator drafts” that give an idea of which animator worked on which scene within Disney shorts and features. Danish director Hans Perk, from A. Film, released many more of those “animator drafts”, and animation historian Mark Mayerson used them to analyze the shorts and features in an unprecedented way and shed fascinating new light on the work of many of Walt’s people. In other words, the more information released, the more people decide to release new information, leading to fresh understanding and knowledge. Of course, this also allowed us to identify new sources of unpublished interviews with Disney artists that will soon appear in Walt’s People: Freddy Moore’s assistant Ken O’Brien by Jenny Lerew, Art Stevens by Pete Docter…

The “quiet revolution” that we see happening on the web brings me to a similar process experienced by Walt’s People. Many key Disney historians have recently given me the authorization to publish their work, as they see this as a way to protect material that was at risk of being lost or irrevocably damaged—some interviews were even preserved in reel-to-reel format! In this volume, Charles Solomon, author of one of my favorite books on Disney animation, The Disney That Never Was, is one of the new key historians joining the Walt’s People team.

Another new participant is Joe Adamson. His oral history with Dick Huemer is the keystone of this volume. I had admired this interview for years after having read excerpts of it in Funnyworld and had always dreamed of releasing a Disney-related uncut version in Walt’s People.

Of course, focusing on Huemer’s career would not have been complete without tackling in-depth the career of his creative alter-ego, Joe Grant. Who better than Michael Barrier to draw interesting and surprising answers from such a notoriously tough interviewee? The Huemer focus also allows us to welcome the third of Walt’s People’s new contributors, Brian Sibley, who appears in this volume as both interviewer and interviewee.

There are many more exciting features in this volume, including a surprising new look at the career of Peter Ellenshaw; the seminal interview with Roy Williams by Don Peri (another important new member of the Walt’s People team), who shows us who the Big Mooseketeer really was; another foray into the world of Disney comics with Dick Moores and Roger Armstrong, thanks to comics expert Alberto Becattini; the second part of Celbi Pegoraro’s interview with Floyd Norman; an interview with Eric Goldberg; and a look at the abandoned project Mary Poppins Comes Back.

My own favorite from a historical point of view, however, is Dave Smith’s chat with Lou Debney, as it gives us a first glimpse at the Disney studio during WWII, a subject that we will explore in much more detail in Walt’s People: Volume 5.

Not enough scope yet for one single volume? So before surrounding ourselves, once again, with Walt’s people, let’s meet Walt’s first star…

Didier Ghez

Didier Ghez has conducted Disney research since he was a teenager in the mid-1980s. His articles about the Disney parks, Disney animation, and vintage international Disneyana, as well as his many interviews with Disney artists, have appeared in Animation Journal, Animation Magazine, Disney Twenty-Three, Persistence of Vision, StoryboarD, and Tomart’s Disneyana Update. He is the co-author of Disneyland Paris: From Sketch to Reality, runs the Disney History blog, the Disney Books Network, and serves as managing editor of the Walt’s People book series.

A Chat with Didier Ghez

If you have a question for Didier that you would like to see answered here, please get in touch and let us know what's on your mind.

About The Walt's People Series

How did you get the idea for the Walt's People series?

GHEZ: The Walt’s People project was born out of an email conversation I conducted with Disney historian Jim Korkis in 2004. The Disney history magazine Persistence of Vision had not been published for years, The “E” Ticket magazine’s future was uncertain, and, of course, the grandfather of them all, Funnyworld, had passed away 20 years ago. As a result, access to serious Disney history was becoming harder that it had ever been.

The most frustrating part of this situation was that both Jim and I knew huge amounts of amazing material was sleeping in the cabinets of serious Disney historians, unavailable to others because no one would publish it. Some would surface from time to time in a book released by Disney Editions, some in a fanzine or on a website, but this seemed to happen less and less often. And what did surface was only the tip of the iceberg: Paul F. Anderson alone conducted more than 250 interviews over the years with Disney artists, most of whom are no longer with us today.

Jim had conceived the idea of a book originally called Talking Disney that would collect his best interviews with Disney artists. He suggested this to several publishers, but they all turned him down. They thought the potential market too small.

Jim’s idea, however, awakened long forgotten dreams, dreams that I had of becoming a publisher of Disney history books. By doing some research on the web I realized that new "print-on-demand" technology now allowed these dreams to become reality. This is how the project started.

Twelve volumes of Walt's People later, I decided to switch from print-on-demand to an established publisher, Theme Park Press, and am happy to say that Theme Park Press will soon re-release the earlier volumes, removing the few typos that they contain and improving the overall layout of the series.

How do you locate and acquire the interviews and articles?

To locate them, I usually check carefully the footnotes as well as the acknowledgments in other Disney history books, then get in touch with their authors. Also, I stay in touch with a network of Disney historians and researchers, and so I become aware of newly found documents, such as lost autobiographies, correspondence with Disney artists, and so forth, as soon as they've been discovered.

Were any of them difficult to obtain? Anecdotes about the process?

Yes, some interviews and autobiographical documents are extremely difficult to obtain. Many are only available on tapes and have to be transcribed (thanks to a network of volunteers without whom Walt’s People would not exist), which is a long and painstaking process. Some, like the seminal interview with Disney comic artist Paul Murry, took me years to obtain because even person who had originally conducted the interview could not find the tapes. But I am patient and persistent, and if there is a way to get the interview, I will try to get it, even if it takes years to do so.

One funny anecdote involves the autobiography of the Head of Disney’s Character Merchandising from the '40s to the '70s, O.B. Johnston. Nobody knew that his autobiography existed until I found a reference to an article Johnston had written for a Japanese magazine. The article was in Japanese. I managed to get a copy (which I could not read, of course) but by following the thread, I realized that it was an extract from Johnston’s autobiography, which had been written in English and was preserved by UCLA as part of the Walter Lantz Collection. (Later in his career Johnston had worked with Woody Woodpecker’s creator.) Unfortunately, UCLA did not allow anyone to make copies of the manuscript. By posting a note on the Disney History blog a few weeks later, I was lucky enough to be contacted by a friend of Johnston's family, who lives in England and who had a copy of the manuscript. This document will be included in a book, Roy's People, that will focus on the people who worked for Walt's brother Roy.

How many more volumes do you foresee?

That is a tough question. The more volumes I release, the more I find outstanding interviews that should be made public, not to mention the interviews that I and a few others continue to conduct on an ongoing basis. I will need at least another 15 to 17 volumes to get most of the interviews in print.

About Disney's Grand Tour

You say that you've worked on this book for 25 years. Why so long?

DIDIER: The research took me close to 25 years. The actual writing took two-and-a-half years.

The official history of Disney in Europe seemed to start after World War II. We all knew about the various Disney magazines which existed in the Old World in the '30s, and we knew about the highly-prized, pre-World War II collectibles. That was about it. The rest of the story was not even sketchy: it remained a complete mystery. For a Disney historian born and raised in Paris this was highly unsatisfactory. I wanted to understand much more: How did it all start? Who were the men and women who helped establish and grow Disney's presence in Europe? How many were they? Were there any talented artists among them? And so forth.

I managed to chip away at the brick wall, by learning about the existence of Disney's first representative in Europe, William Banks Levy; by learning the name George Kamen; and by piecing together the story of some of the early Disney licensees. This was still highly unsatisfactory. We had never seen a photo of Bill Levy, there was little that we knew about George Kamen's career, and the overall picture simply was not there.

Then, in July 2011, Diane Disney Miller, Walt Disney's daughter, asked me a seemingly simple question: "Do you know if any photos were taken during the 'League of Nations' event that my father attended during his trip to Paris in 1935?" And the solution to the great Disney European mystery started to unravel. This "simple" question from Diane proved to be anything but. It also allowed me to focus on an event, Walt's visit to Europe in 1935, which gave me the key to the mysteries I had been investigating for twenty-three years. Remarkably, in just two years most of the answers were found.

Will Disney's Grand Tour interest casual Disney fans?

DIDIER: Yes, I believe that casual readers, not just Disney historians, will find it a fun read. The book is heavily illustrated. We travel with Walt and his family. We see what they see and enjoy what they enjoy. And the book is full of quotes from the people who were there: Roy and Edna Disney, of course, but also many of the celebrities and interesting individuals that the Disneys met during the trip. And on top of all of this, there is the historical detective work, that I believe is quite fun: the mysteries explored in the book unravel step by step, and it is often like reading a historical novel mixed with a detective story, although the book is strict non-fiction.

Walt bought hundreds of books in Europe and had them shipped back to the studio library. Were they of any practical use?

DIDIER: Those books provided massive new sources of inspiration to the Story Department. "Some of those little books which I brought back with me from Europe," Walt remarked in a memo dated December 23, 1935, "have very fascinating illustrations of little peoples, bees, and small insects who live in mushrooms, pumpkins, etc. This quaint atmosphere fascinates me."

What other little-known events in Walt's life are ripe for analysis?

DIDIER: There are still a million events in Walt's life and career which need to be explored in detail. To name a few:

- Disney during WWII (Disney historian Paul F. Anderson is working on this)

- Disney and Space (I am hoping to tackle that project very soon)

- The 1941 Disney studio strike

- Walt's later trips to Europe

The list goes on almost forever.

Other Books by Didier Ghez:

- They Drew as They Pleased: The Hidden Art of Disney's Golden Age (2015)

- Disney's Grand Tour: Walt and Roy's European Vacation, Summer 1935 (2013)

- Disneyland Paris: From Sketch to Reality (2002)

Didier Ghez has edited:

- Walt's People: Volume 15 (2014)

- Walt's People: Volume 14 (2014)

- Walt's People: Volume 13 (2013)

- Walt's People: Volume 12 (20xx)

- Walt's People: Volume 11 (20xx)

- Walt's People: Volume 10 (20xx)

- Walt's People: Volume 9 (20xx)

- Walt's People: Volume 8 (20xx)

- Walt's People: Volume 7 (20xx)

- Walt's People: Volume 6 (20xx)

- Walt's People: Volume 5 (20xx)

- Walt's People: Volume 4 (20xx)

- Walt's People: Volume 3 (2015)

- Walt's People: Volume 2 (2015)

- Walt's People: Volume 1 (2014)

- Life in the Mouse House: Memoir of a Disney Story Artist (2014)

- Inside the Whimsy Works: My Life with Walt Disney Productions (2014)

Dick Huemer talks about accepting a job offer from Walt Disney in 1933—after turning him down once before.

JOE ADAMSON: How was it that you got the opportunity to work for Disney again, after turning him down in 1930 to take a job with Charles Mintz? Did he make you another offer, or did you go to him?

DICK HUEMER: When Mintz tried to cut our salaries during the Depression, we went on strike. And so I left Mintz. Instead of going on strike, though, I went over to Disney’s at last. I had regretted turning him down as he had predicted. Don’t forget Disney was the big boy in those days, and there wasn’t really anybody who was anywhere near him. I went to Ben Sharpsteen, who was my friend, and said, “Well, Ben, I’d like to come and work for Walt now.” And Ben just went and told Walt, and that was all it was.

JA: Was there that much difference in salary?

DH: There was quite a come-down in salary—almost half. Walt was not one for paying big salaries at that time. He cut salaries once, during the Depression. Everybody had to take a cut, but we were willing to do that.

Did I tell you about the first time I went to work for Walt? I was sitting in his sanctum, and we were talking; we were all set, had agreed on how much money and everything. Walt started to tell me that he was going to make a cartoon feature. He was already thinking of it in 1933! Not only that, but it was going to be Snow White. He started telling me a little about the story: how she eats the poison apple and dies, and, as she’s lying there, all the goddamn little animals are looking in the window with tears rolling down… Walt was such a wonderful actor that my throat started to get tight, and my eyes began to get moist at the way he was telling it. To begin with, the idea of doing a cartoon feature was such a brazen, daring idea in 1933. Then he told me that he might also like to have some kind of amusement park some day. The idea, the germ, was not the way it finally turned out, but it was there.

And while we were sitting and talking, in came Charlie Chaplin. I almost fell out of the chair, because after all Charlie Chaplin was one of my idols. And behind him was another one of my idols, H.G. Wells! Chaplin very proudly introduced, not Walt to Wells, but Wells to Walt! “Here’s somebody I want you to meet, Walt Disney, this great guy sitting here.” That was the feeling! It was a wonderful experience, but I don’t know what they said, because I left soon after.

JA: When you started to work for Disney, were you animating?

DH: I animated on a lot of his pictures, like Grasshopper and the Ants, The Tortoise and the Hare, and Water Babies. My first animation was in Lullaby Land and a number of Silly Symphonies. Then I animated on The Wise Little Hen, which was the first time Donald Duck appeared and the first time they used his voice. They hadn’t “found” him yet; they hadn’t determined how to use him. He became a cranky character later on, but in Wise Little Hen he was just a duck who spoke with Clarence “Ducky” Nash’s voice. And I animated the Duck in The Band Concert, which Richard Schickel says is one of the best of Disney’s shorts.

JA: So you did run into the problem of finding the voice for the Duck?

DH: No, that was all done. Walt had determined that. The story as I heard it is that “Ducky” Nash came to Walt looking for a job and demonstrated his voices, and said, “Here’s one that I got. How do you like this? I don’t know what it is.” And did it.

And Walt said, “Why that’s a duck!”

Another picture, which I didn’t animate on, called Orphans’ Benefit, became the first time Donald was a crank and did this come-on-and-fight bit. Dick Lundy animated and deserves credit for that.

And Freddie Spencer deserves credit for having drawn the Duck the way he looks today. The way we animated him at first—the original models were made by somebody else—Donald had a long, sort of pointed beak. Freddie Spencer became the Donald Duck specialist. He wasn’t only good but awfully fast; when Walt instituted the system of paying bonuses, I think he had Fred in mind, because he was the principal beneficiary. He made an awful lot of money on his duck stuff. He was red-headed and had a very unfortunate disfigurement: his lower jaw had been caved in as a child by a baseball bat, so he had a big hollow on one side of his face. If he’d had lived, he would have retired rich, but he was killed in an automobile accident in the thirties coming home from a football game.

JA: Did Walt actually discuss character and motivation over the storyboards?

DH: Did he? You bet your life! Storyboards! Sweatbox! Lunchroom! That’s the one thing that we got all the time. When I went to work for him, he was doing Silly Symphonies, and the characterizations were very clear-cut in those things. For instance, when they did The Tortoise and the Hare, it was clearly laid out to have the hare act the way he did, bombastic and boastful, yet talented. That was good, clear characterization. The tortoise was definitely staged as a stupid guy who could good-naturedly be taken advantage of. Actually, he won by default. This was the kind of strong characterization that Walt always insisted on. If anybody else had done The Tortoise and the Hare, it would have been a series of assorted gags about running, one after another. Not all this clever, boastful stuff, like stopping with the little girls and bragging and being admired, and showing off the way he could play tennis with himself.

Walt would take stories and act them out at a meeting, kill you laughing they were so funny. And not just because he was the boss either. There it would be! You’d have the feeling of the whole thing; you’d know exactly what he wanted. We often wondered if Walt could have been a great actor, or a comedian. The acting in them was what made his pictures so great. And the characterizations in Snow White were beautiful as well: Just think, taking each one of those dwarfs and making each one an entirely different personality. Seven of the little bastards! It was just unheard of!

Walt worked out his stories down to the last blink of the eye. In other cartoon studios, we might do little pre-sketches, but there was no time for real analysis. But that’s what Walt was able to do, give time to do these things, because he now for the first time had the money coming in on his licensee projects. Even so, he worked on a pretty short budget; we had to have a picture finished about every two weeks. Walt’s pictures cost him much more than he got for them, at first; even Three Little Pigs made not so much money as you may think. We’d sometimes come back at night, just to talk about the stories and save animation time. I don’t know how other studios operated around that time; I guess they were more or less one like the other.

The only ones who did anything comparable at all—and they didn’t ever quite reach Disney—were [Hugh] Harman and [Rudy] Ising. They were the only ones who ever had some of the feeling of a Disney. They occasionally would turn out a really good film. They would make a cartoon against war, which wasn’t half bad. Once, when they were in trouble with Schlesinger, Disney helped them out financially.

There’s a famous story about Walter Lantz. He used to give runnings of his cartoons in theaters for kids on Saturday. And one time he ran all his Oswalds, and then he appeared personally on stage and talked to the kids. When it was over, he said, “Now what is the best cartoon in the world?”

And all the kids yelled out, “Mickey Mouse!” This actually happened!

Great as Walt undeniably was, he never, in the opinion of some, would have accomplished what he did if he hadn’t attracted such talent. I’ve heard guys say, “All right, Walt’s a genius, but he couldn’t have done it with Zulus or Eskimos.” Like Napoleon had to have brilliant generals and marshals who were talented tacticians in their own right, Walt had to have this group of—as I call them—his paladins.

For instance, Norm Ferguson started as a bookkeeper at Paul Terry’s Aesop’s Fables. Then one day he thought he’d like to animate, tried it, and didn’t get much encouragement, because he left Terry’s and accepted an offer from Disney. Walt was hard-pressed for men in those days, and he was trying almost anybody who showed talent. Fergy hadn’t animated much, but he fell right into it. He was a naturals, like Freddie Moore or Ward Kimball. It just flowed out of their pencils, or heads, or wherever talent flows from. In every studio there was, and still is, the so-called Best Animator. When I came to work at Disney’s in 1933, Norm, or Fergy, was IT—not only the best at Disney’s, but consequently the best in the world.

Walt was just crazy about Fergy’s animation and with damn good reason. Fergy’s characters lived and breathed and seemed to have actual thought processes. His sequence with Pluto and the flypaper, for instance, was a real classic. It still holds up as well as ever today. I saw it just last week in connection with a show we’re doing for TV this Christmas, and we all laughed as much as ever. Fergy wasn’t just a Pluto and Pegleg Pete animator, either. He did all the Wicked Witch animation in Snow White.

Once, at a meeting, right in front of everybody, Walt said to Fergy, “Fergy, you’re a great actor.”

And Fergy sort of simpered and said, “Well, I don’t know.”

And Walt said, “Yes, you are. That’s why your animation is so good, because you feel. You feel what these characters feel.”

Fergy was one sweet little guy, that’s how everyone felt about him, and in his own way, he was also one of Walt’s demi-geniuses.

Ham Luske, long before he ever applied for a job in Hollywood, wanted to be an animator. He had worked up in San Francisco, I think, on a newspaper. Without the least bit of knowledge of animation, he made a pencil test of a tennis player serving, which was just great. I imagine he had probably copied live action in some way, but he never disclosed it.

Wilfred Jackson has been written up quite a bit; he was a very important man at Disney’s. I worked with him a lot. He was the only cartoon director who came to work in sneakers; he was quite careless in his dress. He was one of Walt’s very first men, came out of art school poor as a church mouse, hardly had the fare to get to the studio. He was very instrumental in working out the idea of music with a cartoon.

Continued in "Walt's People: Volume 4"!

John Hench talks philosophically about the connections between fantasy, reality, and myth.

ARMAND EISEN: It’s been said that in Disneyland, the fantasy elements of the comic strip and the animated film have been given three-dimensional form in which the audience participates.

JOHN HENCH: Yes, only I have a certain disagreement with that word “fantasy”. Commonly, “fantasy” is used in contrast to “reality”. These terms may be necessary as a convenience, but they don’t define anything. As a matter of fact, so-called “reality” is more fantastic than “fantasy”. More often than not, they switch places. And if you try to judge things on that basis, you’re completely lost; the minute you say, “That’s too fantastic to believe,” you’re sunk. Nothing you can consider is too fantastic to be real.

When someone compares Disneyland or cartoons to fantasy, it really doesn’t mean anything. Those two terms are not only interchangeable, they often overlap so that even for convenience’s sake, they have no meaning.

AE: Myth embodies certain universal ideas. Let’s consider the Greek myth of Odysseus; on the superficial level, his adventures are fantastic. But on the symbolic level, they are dealing with very real human ideas.

JH: Yes, and I think they are more real than we give them credit for. In a symbolic way, they reflect principles of which we are the result. They are survival patterns, the “realest” things we know. These stories hold them up to us. We are here; we were there at one point, and these patterns still hold true.

Take fairytales, so-called “children’s stories”—they reflect something else entirely. They all fall into a pattern, often a Biblical pattern. In the case of Cinderella, she was very high born. Through some set of circumstances, she was reduced to a kitchen maid. This is clearly Man being kicked out of Eden. Along comes a redeemer, a prince, and there’s always a gimmick, a key, a talisman. In Sleeping Beauty it’s a kiss, in Cinderella it’s a glass slipper. And the person is returned to the former state.

It’s something we seem to have acquired. I don’t know whether it came from actual experience or whether it’s an instinctive concept.

AE: Campbell and others talk about universal myths, which manifest themselves in different cultures in different forms. You suggest that the myth of Cinderella is in this category; that man has a vision of an exalted position he once occupied but has lost. This memory/ frustration lives within the greater cultural consciousness.

JH: And man’s faith that he’ll be redeemed, that someone will find the gimmick and restore him to what he believes he really is.

Cartoons reflect those things. Every successful cartoon has that in its basis. I think we, as humans, have only one dynamic, one thing that makes us tick: survival. The single command: survive. We have inherited the patterns designed and tested for 100 million years. Whether we need them now or not, we can’t ignore them. Image is the most powerful way to it.

The whole mechanism of vision is extraordinary. It’s hooked up to a little computer, and the memory banks keep all the information stored up. A baby duck that has been hatched with chickens has a little reference in the DNA chapter all about water. And even though he considers himself a chicken, he walks over to the water with confidence and swims. We are in the same predicament; we have all that locked in. I think our environment has outstripped our evolutionary processes. We couldn’t evolve as fast as our environment, so we carry a lot of useless things that color our world. And that’s what cartooning is all about.

AE: Jung says that modern man has lost a great deal of his spiritual essence. We have become “rational,” cut off from nature, and we’ve lost our mysticism. Do you feel that the Disney works are, through these mythic structures such as Cinderella, restoring this subliminal mysticism—and this is why we respond to it so strongly?

JH: Yes, in a way. We haven’t lost it, we’ve simply ignored it. And we pay for this in a kind of underlying anxiety, a base which we find very difficult to touch. Again, the question is survival. The things that reassure us, that make these survival instincts tangible, make us happy. We often misunderstand the stimulation for pleasure. Battle really has a lot to do with pleasure; pleasure is sweetest when we are triumphant, when we have survived. The implication is that we have one struggle behind, and we are that much stronger for the next one. That is, I think, why kids love being frightened in haunted houses and some of our rides—they come out of the threat to their survival. They are here, they beat it, and a wave of pleasure comes over them for that.

The cartoon tends to ensure that. It gives us back some of those symbols, saying, “You are going to survive.” The old morality plays were doing the same thing.

AE: Ray Bradbury wrote an article some years ago on the horror film and why our culture needs the horror film…

JH: Yes, it’s the same thing that he was talking about. Ray is a good friend of this place, he comes here often. We speak the same language, oddly enough, and he’s one of the true “intellectuals” who have noticed something different going on in Disneyland and with Walt in particular.

Walt had a very acute awareness of what he was dealing with. He wasn’t the most articulate guy when it came to rationalizing himself, but I suppose that’s because he was an intuitive man. People with such a very high awareness this way are not apt to be good at explaining why. To communicate, you have to start with a common ground. That’s the nature of Gestalt—you have to provide something as a ground, so that when you introduce a new form it takes the proper identity. You can’t always do that to people, and the identity is lost or distorted.

Continued in "Walt's People: Volume 4"!

About Theme Park Press

Theme Park Press is the world's leading independent publisher of books about the Disney company, its history, its films and animation, and its theme parks. We make the happiest books on earth!

Our catalog includes guidebooks, memoirs, fiction, popular history, scholarly works, family favorites, and many other titles written by Disney Legends, Disney animators and artists, Mouseketeers, Cast Members, historians, academics, executives, prominent bloggers, and talented first-time authors.

We love chatting about what we do: drop us a line, any time.

Theme Park Press Books

The Unauthorized Story of Walt Disney's Haunted Mansion The Ride Delegate 501 Ways to Make the Most of Your Walt Disney World Vacation The Cotton Candy Road Trip The Wonderful World of Customer Service at Disney Disney Destinies Disney Melodies The Happiest Workplace on Earth Storm over the Bay A Historical Tour of Walt Disney World: Volume 1 Mouse in Transition Mouseketeers Down Under Murder in the Magic Kingdom Walt Disney and the Promise of Progress City Service with Character Son of Faster Cheaper A Tale of Two Resorts I Saw Ariel Do a Keg Stand The Adventures of Young Walt Disney Death in the Tragic Kingdom Two Girls and a Mouse Tale Ears & Bubbles The Easy Guide 2015 Who's the Leader of the Club? Disney's Hollywood Studios Funny Animals Life in the Mouse House The Book of Mouse Disney's Grand Tour The Accidental Mouseketeer The Vault of Walt: Volume 1 The Vault of Walt: Volume 2 The Vault of Walt: Volume 3 Who's Afraid of the Song of the South? Amber Earns Her Ears Ema Earns Her Ears Sara Earns Her Ears Katie Earns Her Ears Brittany Earns Her Ears Walt's People: Volume 1 Walt's People: Volume 2 Walt's People: Volume 13 Walt's People: Volume 14 Walt's People: Volume 15

Write for Theme Park Press

We're always in the market for new authors with great ideas. Or great authors with new ideas. Whichever type of author you are, we'd be happy to discuss your book. Before you contact us, however, please make sure you can answer "yes" to these threshold questions:

Is It Right for Us?

We specialize in books that have some connection to Disney or theme parks. Disney, of course, has become a broad topic, and encompasses not just theme parks and films but comic books, animation, and a big chunk of pop culture. Your book should fit into one (or more) of those broad categories.

Is It Going to Make Money?

There's never a guarantee that any book will make money, but certain types of books are less likely to do so than others. They include: hardcovers, books with color photos, and books that go on forever ("forever" as in 400+ pages). We won't automatically turn down these types of books, but you'll have to be a really good salesman to convince us.

Are You Great to Work With?

Writing books and publishing books should be fun. The last thing you want, and the last thing we want, is a contentious relationship. We work with authors who share our philosophy of no drama and zero attitude, and the desire for a respectful, realistic, mutually beneficial partnership.

If you said "yes" three times, please step inside.