- Visit the Imagineering Graveyard

- Now Sailing: "Skipper Stories" - Tales from the Jungle Cruise

- Coming Soon: The biography of Disney animator Jack Hannah

- Coming Soon: A Haunted Mansion anthology

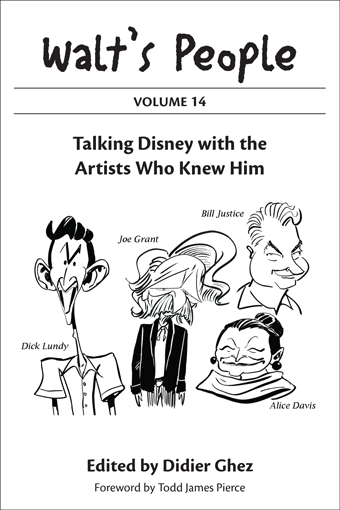

Walt's People: Volume 14

Talking Disney with the Artists Who Knew Him

by Didier Ghez | Release Date: April 29, 2014 | Availability: Print, Kindle

Disney History from the Source

The Walt's People series is an oral history of all things Disney, as told by the artists, animators, designers, engineers, and executives who made it happen, from the 1920s through the present.

Walt’s People: Volume 14 features appearances by Carman Maxwell, Dick Lundy, Phil Klein, Zach Schwartz, Ray Patterson, Marge Champion, Joe Grant, Bob Jones, Bob Baker, Bill Justice, Irvin Graham, Lillian Disney, Carson Van Osten, Bruce Bushman, Bob Mattey, Chris Mueller Jr., Arthur J. Vitarelli, Alice Davis, Lucile Bosché, Admiral Joe Fowler, and Eddie Sotto, plus articles by Vincent Randle and David Culbert, and the Holling C. Holling letters.

Among the hundreds of stories in this volume:

- MARGE CHAMPION remembers what it was like to dance and model as the live-action reference for Snow White.

- ALICE DAVIS reveals the trials and tribulations of designing clothes for the pirates—and the Redhead—in Pirates of the Caribbean.

- BOB MATTEY explains how he built the animals for the Jungle Cruise, and the many things that went wrong.

- ADMIRAL JOE FOWLER talks about facing down gunboats in 1920s China and buying up land for Walt in Florida.

- EDDIE SOTTO describes fascinating attractions never built, including piranha pits, a new Jungle Cruise based on Apocalypse Now, and an encounter with Maleficent in the Dragon’s Lair.

The entertaining, informative stories in every volume of Walt's People will please both Disney scholars and eager fans alike.

Table of Contents

Foreword

Introduction

Carman Maxwell by Bob Thomas

Dick Lundy by Mark Mayerson and Leonard Maltin

Phil Klein by Leonard Maltin

Zach Schwartz by Leonard Maltin

Ray Patterson by John Culhane

Marge Champion by Didier Ghez

Joe Grant by John Canemaker

Bob Jones by Dave Smith

Bob Baker by Jim Korkis and Didier Ghez

A Life Rendering: The Unrealized Art of Richmond "Dick" Kelsey by Vincent Randle

Eric Knight at the Walt Disney Studio by David Culbert

The Holling C. Holling Lettters

Bill Justice by John Culhane

Irvin Graham by John Culhane

Lillian Disney by Michael Broggie

Carson Van Osten by Alberto Becattini

Bruce Bushman by George Sherman

Bob Mattey by George Sherman

Chris Mueller Jr. by Dave Smith

Arthur J. Vitarelli by John G. West

Alice Davis by Charles Solomon

Lucile Bosché by Didier Ghez

Joe Fowler by Harry Wessel

Eddie Sotto by Didier Ghez

Bibliography

Foreword

With this, the fourteenth volume of interviews and uncollected writing, Walt’s People again demonstrates its unparalleled commitment to preserve the memories of the men and women who worked for Walt Disney and The Walt Disney Company. This series is not only the most complete collection of interviews focused on the Disney Studio, it is the most complete collection of interviews focused on any studio. It is a unique window into the previous century, when American visions shaped the world’s imagination. In fact, I can think of no single force whose influence more significantly framed the character of our interior lives, particularly when we were young, than that of Disney. Today, largely due to its success, the Disney Company is often perceived in these exact terms, primarily as a force. Yet in Walt’s People, that force is broken down into its component parts: animators, accountants, engineers, inkers, machinists, and technicians. In these pages, the studio is not primarily a company, but rather a group of individuals, all sharing the personal and professional challenges they faced at work, as the eyes of the world looked on.

I first learned about Walt’s People in a review written by Jim Hill. Back then, in 2005, when the word “blog” was a newly minted term, many historians with a longstanding interest in animation were learning about the rapidly expanding base of information newly assembled and presented to the public through blogs and print-on-demand publications. At the time I was not living in California; I was living in South Carolina, which was far from the center of pretty much everything. Jim’s was one of three or four blogs I checked each day. The review for Walt’s People: Volume 1 included a short excerpt from an interview with Herb Ryman, one of the original designers of Disneyland. In it, Ryman recounted the evening in which he climbed with Walt to the top of an observation tower at Disneyland. During the construction of the park, the towers served many purposes: They allowed art directors and engineers a bird’s-eye view of the park; they allowed for aerial photography; they housed timelapse cameras that, in part, date-stamped images to verify when projects were completed. This story would’ve taken place in December of 1954, January of 1955 at the latest. Ryman recalled that as his boss stared out at the property, his eyes grew damp with frustration. Disneyland, at that time, Ryman explained: “was nothing but a sea of drains and ditches and nothing above ground”. In Ryman’s memory, Walt turned to him and said: “I have half of the money spent and nothing to show for it.”

For me this story was new. I’d not seen it anywhere—a tale in which the construction of Disneyland was reduced to the emotional experience of two men. On TV, I’d seen footage of long-reach cranes lifting the Moonliner rocket into place. I’d watched (and rewatched) time-lapse footage of carpenters transforming skeletal buildings into turn-of-thecentury wonders. but rarely did I find interviews that presented the personal struggles—the joys and frustrations—that flickered beneath the Disneyland project.

That same morning, immediately after reading Jim’s review, I ordered the first volume of Walt’s People. A few months later, I ordered Volume 2. And now, eight years later, I’m trying to sum up the importance of this series, as I see it, into a few pages.

To be a good historian is a difficult thing, especially if you acknowledge that the ownership of history—as well as its meaning—is spread out among many participants. For the past decade, I’ve done my best to present a narrative history of the Disney Studio, particularly those years from 1948 to 1966. I see narrative history as having two primary emphases: narrative history contextualizes historical events so readers understand their influences and consequences; narrative history also depicts the experience of individuals to demonstrate how (in the case of the Disney Company) artistic and business forces shape not only culture but individual lives. No set of books has been more useful to me in this work than Walt’s People.

Walt’s People is a well-arranged, multi-vocal presentation of history. The voices in Walt’s People don’t always agree with each other. Most everyone, it seems, understands the character of Walt Disney in a unique light: He is a bear, an uncle, a man frustrated with stockholders. For me, the richness of history rests not only on the specificity of each person’s memory but in the conflicting space in between.

Like a cocktail party where people gossip about work, or a family dinner where parents discuss the day’s events, the voices in Walt’s People, in their best moments, allow readers to participate vicariously in the working of the studio. The stories here are juiced with energy, delivered with clarity as though the events happened earlier that day—and not thirty or sixty years in the past. These interviews humanize history: they give it shape and personality. Moreover, they allow readers the pleasurable illusion that they are standing shoulder-to-shoulder with the men and women who worked with Walt Disney and at the company he founded.

If you’ve never read a volume of Walt’s People, you’re in for a treat. If you’ve spent time in this series, you already know what lies ahead. Mysteries are solved, secrets revealed, the past made tangible with words. We—as readers, researchers, and historians—owe a sizable debt to Didier Ghez, who has shepherded this series through fourteen volumes. Through his work, the details of the early studio—and to some extent, of the twentieth century as well—are preserved for us and for generations to come, all of those children who will someday look up at the movie screen with wonder.

Introduction

Having spent the last two-and-a-half years researching my new book about Walt’s trip to Europe in 1935 (Disney’s Grand Tour), I was amazed by the sheer quantity of brand-new Disney history-related information which can be unearthed when one focuses on a very specific aspect of Disney’s life and career.

This is also true when it comes to unearthing never-released-before memoirs, autobiographies, and interviews. A few months ago, thanks to Michael Barrier, I stumbled upon the “lost” autobiography of Homer Brightman, which was released earlier this year by Theme Park Press; a few days later, I discovered a short autobiography of the English Disney artist Wilfred Haughton; and just last week, with the help of Joe Campana, we learned that the notes for Eric Larson’s autobiography, 40 Years at the Mouse House, had survived. In other words, as Bill Watterson’s Calvin and Hobbes would have said, there are still “treasures everywhere”.

All of these documents have been discovered following the tiniest of leads: A letter hidden in one of Michael Barrier’s files, a brief mention of a mysterious notebook in a letter from Wilfred Haughton to Denis Gifford, a sentence in an interview with Burny Mattinson. In other words, when looking for hidden treasures, do not overlook any clue, no matter how tiny, and share the information with the other historians you know. United we are definitely stronger.

This volume, once again, is full of those recently uncovered documents: the highly readable Holling C. Holling letters, which open a window on life at the studio during World War II, the barely known interviews of George Sherman with Imagineers Bruce Bushman and Bob Mattey, or the last interview with Joe Fowler. One of the central themes, this time around, is the Character Model Department and Disney’s story artists, thanks to interviews with Joe Grant and Bob Jones, correspondence with Eric Knight, and a long essay by Vincent Randle about Dick Kelsey. To top it off (and to the despair of my publisher), I also decided to include two almost-book-length interviews: one with special-effects master Art Vitarelli and one with legendary Imagineer Eddie Sotto.

But before reaching the late 1990s with Eddie, let’s take a trip back to the early 1920s, thanks to Carman Maxwell.

Didier Ghez

Didier Ghez has conducted Disney research since he was a teenager in the mid-1980s. His articles about the Disney parks, Disney animation, and vintage international Disneyana, as well as his many interviews with Disney artists, have appeared in Animation Journal, Animation Magazine, Disney Twenty-Three, Persistence of Vision, StoryboarD, and Tomart’s Disneyana Update. He is the co-author of Disneyland Paris: From Sketch to Reality, runs the Disney History blog, the Disney Books Network, and serves as managing editor of the Walt’s People book series.

A Chat with Didier Ghez

If you have a question for Didier that you would like to see answered here, please get in touch and let us know what's on your mind.

About The Walt's People Series

How did you get the idea for the Walt's People series?

GHEZ: The Walt’s People project was born out of an email conversation I conducted with Disney historian Jim Korkis in 2004. The Disney history magazine Persistence of Vision had not been published for years, The “E” Ticket magazine’s future was uncertain, and, of course, the grandfather of them all, Funnyworld, had passed away 20 years ago. As a result, access to serious Disney history was becoming harder that it had ever been.

The most frustrating part of this situation was that both Jim and I knew huge amounts of amazing material was sleeping in the cabinets of serious Disney historians, unavailable to others because no one would publish it. Some would surface from time to time in a book released by Disney Editions, some in a fanzine or on a website, but this seemed to happen less and less often. And what did surface was only the tip of the iceberg: Paul F. Anderson alone conducted more than 250 interviews over the years with Disney artists, most of whom are no longer with us today.

Jim had conceived the idea of a book originally called Talking Disney that would collect his best interviews with Disney artists. He suggested this to several publishers, but they all turned him down. They thought the potential market too small.

Jim’s idea, however, awakened long forgotten dreams, dreams that I had of becoming a publisher of Disney history books. By doing some research on the web I realized that new "print-on-demand" technology now allowed these dreams to become reality. This is how the project started.

Twelve volumes of Walt's People later, I decided to switch from print-on-demand to an established publisher, Theme Park Press, and am happy to say that Theme Park Press will soon re-release the earlier volumes, removing the few typos that they contain and improving the overall layout of the series.

How do you locate and acquire the interviews and articles?

To locate them, I usually check carefully the footnotes as well as the acknowledgments in other Disney history books, then get in touch with their authors. Also, I stay in touch with a network of Disney historians and researchers, and so I become aware of newly found documents, such as lost autobiographies, correspondence with Disney artists, and so forth, as soon as they've been discovered.

Were any of them difficult to obtain? Anecdotes about the process?

Yes, some interviews and autobiographical documents are extremely difficult to obtain. Many are only available on tapes and have to be transcribed (thanks to a network of volunteers without whom Walt’s People would not exist), which is a long and painstaking process. Some, like the seminal interview with Disney comic artist Paul Murry, took me years to obtain because even person who had originally conducted the interview could not find the tapes. But I am patient and persistent, and if there is a way to get the interview, I will try to get it, even if it takes years to do so.

One funny anecdote involves the autobiography of the Head of Disney’s Character Merchandising from the '40s to the '70s, O.B. Johnston. Nobody knew that his autobiography existed until I found a reference to an article Johnston had written for a Japanese magazine. The article was in Japanese. I managed to get a copy (which I could not read, of course) but by following the thread, I realized that it was an extract from Johnston’s autobiography, which had been written in English and was preserved by UCLA as part of the Walter Lantz Collection. (Later in his career Johnston had worked with Woody Woodpecker’s creator.) Unfortunately, UCLA did not allow anyone to make copies of the manuscript. By posting a note on the Disney History blog a few weeks later, I was lucky enough to be contacted by a friend of Johnston's family, who lives in England and who had a copy of the manuscript. This document will be included in a book, Roy's People, that will focus on the people who worked for Walt's brother Roy.

How many more volumes do you foresee?

That is a tough question. The more volumes I release, the more I find outstanding interviews that should be made public, not to mention the interviews that I and a few others continue to conduct on an ongoing basis. I will need at least another 15 to 17 volumes to get most of the interviews in print.

About Disney's Grand Tour

You say that you've worked on this book for 25 years. Why so long?

DIDIER: The research took me close to 25 years. The actual writing took two-and-a-half years.

The official history of Disney in Europe seemed to start after World War II. We all knew about the various Disney magazines which existed in the Old World in the '30s, and we knew about the highly-prized, pre-World War II collectibles. That was about it. The rest of the story was not even sketchy: it remained a complete mystery. For a Disney historian born and raised in Paris this was highly unsatisfactory. I wanted to understand much more: How did it all start? Who were the men and women who helped establish and grow Disney's presence in Europe? How many were they? Were there any talented artists among them? And so forth.

I managed to chip away at the brick wall, by learning about the existence of Disney's first representative in Europe, William Banks Levy; by learning the name George Kamen; and by piecing together the story of some of the early Disney licensees. This was still highly unsatisfactory. We had never seen a photo of Bill Levy, there was little that we knew about George Kamen's career, and the overall picture simply was not there.

Then, in July 2011, Diane Disney Miller, Walt Disney's daughter, asked me a seemingly simple question: "Do you know if any photos were taken during the 'League of Nations' event that my father attended during his trip to Paris in 1935?" And the solution to the great Disney European mystery started to unravel. This "simple" question from Diane proved to be anything but. It also allowed me to focus on an event, Walt's visit to Europe in 1935, which gave me the key to the mysteries I had been investigating for twenty-three years. Remarkably, in just two years most of the answers were found.

Will Disney's Grand Tour interest casual Disney fans?

DIDIER: Yes, I believe that casual readers, not just Disney historians, will find it a fun read. The book is heavily illustrated. We travel with Walt and his family. We see what they see and enjoy what they enjoy. And the book is full of quotes from the people who were there: Roy and Edna Disney, of course, but also many of the celebrities and interesting individuals that the Disneys met during the trip. And on top of all of this, there is the historical detective work, that I believe is quite fun: the mysteries explored in the book unravel step by step, and it is often like reading a historical novel mixed with a detective story, although the book is strict non-fiction.

Walt bought hundreds of books in Europe and had them shipped back to the studio library. Were they of any practical use?

DIDIER: Those books provided massive new sources of inspiration to the Story Department. "Some of those little books which I brought back with me from Europe," Walt remarked in a memo dated December 23, 1935, "have very fascinating illustrations of little peoples, bees, and small insects who live in mushrooms, pumpkins, etc. This quaint atmosphere fascinates me."

What other little-known events in Walt's life are ripe for analysis?

DIDIER: There are still a million events in Walt's life and career which need to be explored in detail. To name a few:

- Disney during WWII (Disney historian Paul F. Anderson is working on this)

- Disney and Space (I am hoping to tackle that project very soon)

- The 1941 Disney studio strike

- Walt's later trips to Europe

The list goes on almost forever.

Other Books by Didier Ghez:

- They Drew as They Pleased: The Hidden Art of Disney's Golden Age (2015)

- Disney's Grand Tour: Walt and Roy's European Vacation, Summer 1935 (2013)

- Disneyland Paris: From Sketch to Reality (2002)

Didier Ghez has edited:

- Walt's People: Volume 15 (2014)

- Walt's People: Volume 14 (2014)

- Walt's People: Volume 13 (2013)

- Walt's People: Volume 12 (20xx)

- Walt's People: Volume 11 (20xx)

- Walt's People: Volume 10 (20xx)

- Walt's People: Volume 9 (20xx)

- Walt's People: Volume 8 (20xx)

- Walt's People: Volume 7 (20xx)

- Walt's People: Volume 6 (20xx)

- Walt's People: Volume 5 (20xx)

- Walt's People: Volume 4 (20xx)

- Walt's People: Volume 3 (2015)

- Walt's People: Volume 2 (2015)

- Walt's People: Volume 1 (2014)

- Life in the Mouse House: Memoir of a Disney Story Artist (2014)

- Inside the Whimsy Works: My Life with Walt Disney Productions (2014)

In this excerpt, Disney Legend Alice Davis tells interviewer Charles Solomon about her marriage to Marc Davis, the Disney event that nearly led to their divorce, and how she designed clothing for the pirates (of the Caribbean) and the infamous Redhead.

Alice Estes Davis was born in Escalon, California, in 1929. She grew up in Los Angeles, not far from the old Disney Studio on Hyperion Boulevard. As a child, she haunted the galleries of the nearby Chouinard Art Institute. She later won a scholarship to Chouinard, planning to study animation, but the only place available was in costume design. As a work-scholarship student, she took the evening animation drawing class. Her job was to bring “two perfect pieces of white chalk” to the professor, Marc Davis. After graduating, Alice worked as an assistant designer in a lingerie factory. She renewed her acquaintance with Marc in 1952, when a friend asked her to invite him to a going-away party for another former student. Alice and Marc were married in June, 1956; they remained together until his death in 2000.

Charles Solomon: How did you first meet Walt?

ALICE DAVIS: Marc and I had been married for about 10 months; we had just bought this house, which was a fixer-upper. I was taking wallpaper off walls and sanding doors, so I called Marc and said: “You’re taking me out to dinner tonight: I’m too tired to cook.” He took me to the Tam O’Shanter, and we were having a drink when this hand appeared on Marc’s shoulder. I looked up and into the face of Walt Disney. Walt kind of smiled and said to Marc: “Is this your new bride?” So Walt sat down, had a drink with us, and asked what I did professionally. He said: “I like the way you speak of your profession; you seem to know what you’re talking about. I’d like to have you work for me sometime—you’ll get a call.” And I thought: “Sure I will.”

He didn’t know I had already worked for him; I had done the costume for Helene Stanley for the live action of Briar Rose in the forest. Marc had told me how he wanted the skirt to flow when she was turning and gave me a sketch of the clothing and it worked out very well. I enjoyed it and I was pleased that I was able to get the material to work the way he wanted it. So I didn’t say anything then.

CS: Then you went on to work for him officially.

I got a call from Walt’s secretary out of the blue. He wanted to know if I’d like to do the costumes for It’s a Small World. And I said: “Would I! It’s a lot better than scraping paint off the walls.” She said: “Be here at 9 o’clock tomorrow morning.”

Not only did I work with Marc, I got to work with Mary Blair, one of my idols. She set all the colors for the costumes. I did the research and made pencil sketches. We would discuss the colors, and I’d take fabric swatches or colored paper and staple them to copies of the sketches. We had just one year to put the whole thing together to open in New York, so there wasn’t time for a lot of meetings. They were just doing the clothes and weren’t making any patterns. I said: “You have to make patterns because if something happens to a costume, you have to have a pattern to make another one very quickly.” So I showed them how to do the patterns. We got all the costumes made, and put the ride together on Stage One. We listened to “It’s a Small World” from early morning ’til late evening, day after day after day. They only had one tape and that tape made the dolls work. I was never able to get the man handling the sound to turn it down.

CS: You told me a funny story about meeting Walt on-site in New York.

Just as Marc and I were coming over the bridge to go out, Walt and the CEO came around the curve. Walt saw us and yelled: “Alice, how come you put long pantaloons on the can-can girls?” I knew he didn’t want a long story about how we couldn’t keep the skin on the knees from tearing and we’d had to make long pantaloons to cover up the problem, so I said: “You told me you wanted a family show, Walt!” They all started laughing, and Marc and I took off.

CS: After Small World, you went on to create the costumes for Pirates of the Caribbean.

I’ve always said I graduated from sweet little children to dirty old men overnight. Actually, there was a break for a while, but when the [World’s] Fair was over and everybody got back they started on Pirates. I got a call stating they thought the job I did on the Small World was very good and they’d like to have me do the Pirates. I said to Marc, “I’d like to do it,” and he said “fine,” so I went to work.

As far as I’m concerned, Marc designed the costumes: I only redesigned things when there was a mechanical problem. Marc had one of the Redhead’s guards in a tank top, but we couldn’t do it because the skin kept tearing on the shoulders, so I had to put a shirt on him.

CS: The Redhead has always been a stand-out.

She was a chore because the figures are made out of a very strong, clear plastic. They would sculpt the figure, then make molds, cutting an oval out of, say, the back of the knee, so you could bend the leg. Inside the plastic would be the pipes and wires for the hydraulic system. I didn’t particularly like working around the figures when they were in operation, because if you forgot that a certain time an arm came down, it could knock you for a loop.

To make the Redhead work the way they wanted, they cut the plastic off right underneath the bust and at the top of her hips—and she had quite a shape. This was where having been a girdle designer came in handy because I knew elastic materials and how to work with them. I made a corset that went from the bottom of the bust to the hips and formed her waist. I used grippers to hold the corset in place, and had them cut plastic stays for me, which worked fine. They were strong enough to twist and bend for 16 hours a day.

I found that you had to make sure the material wouldn’t get caught between the moving pieces at a joint. I lined everything with either taffeta or satin so it would slide over the surface of the plastic. Some people thought I was spending too much money and that I didn’t need to line everything, but I went on the ride not too long ago, and garments I made are still in use.

CS: Some of the Pirates posed special problems.

There was a tremendous satisfaction in figuring out how to make the costumes work without seeing the wires. I don’t know if I could make clothes for normal people again. For example, the pirate that’s lying on the cannon barrel: all of the controls came up through his stomach and chest, his hands were bolted together, his elbows and knees were bolted to the cannon barrel, and his feet were bolted together. The front of his shirt was maybe 12” wide, and the back of the shirt was a tremendous volume of material. The pant legs looked like a gorilla suit because they had to bend to fit the legs without making it look like the material was all bunched up. One suit had to fit two characters at the same time because one was sitting on top of the other holding a gun: there was no way you could get that to work any other way but to do the two figures as one. I spent many nights awake, staring at the ceiling, figuring out how to put things together.

CS: What was it like to work for Walt?

Making Walt happy meant giving him top quality: He always wanted the best. On Small World, I asked him how much I would be allowed to spend on the costumes, and he said: “We don’t think that way. This show is going to be about the detail and the flavor of the dolls: If they’re very cute and intricate and have the flavor of the country, that’s what I want. We don’t worry about what they cost. I have a building full of men over there that are supposed to do that. We’re supposed to produce the best because the public will always pay you back.”

CS: Why did you stop working at the park?

I stopped working because there were problems with my being Marc’s wife.

I think people thought I was freeloading. We were also friends with Roy and Edna Disney; whenever Roy would come into the shop with, say, the head of the Bank of America, he would bring them over and introduce them to me, and always give me a hug and kiss me on the cheek. People thought it showed I was freeloading. Little did they know that they were making three times as much as I did because I was being paid as a jobber. If there was a holiday, I didn’t get paid for it, and if I missed a day, I didn’t get paid for it, and if I worked seven days, I still got paid for five.

Also, I was trying to get them to let me make two costumes for each figure because if something happens, you have to have another costume ready. It doesn’t take any more time or effort to cut two costumes. When the seamstress knows how to put it together, she can put the two together faster. But one group started complaining about that and the interlining. They would call Marc into the office, then they would call me in and dress me down in front of Marc. That did not sit well, and that did not make for a happy home. I did the General Electric Show after Pirates, and Marc said: “When you’re done with the General Electric Show, you’re not working there any longer or it’s a divorce.” So I stopped.

CS: You were originally interested in animation, not costumes or fashion design.

I always wanted to be an animator, but that just didn’t happen in my time. Retta Scott was the only woman animator I knew of. I’m not broken-hearted over it, although I would have loved to try it. I took animation drawing at Chouinard—Mrs. Chouinard let me take it as an extra class because I wanted to so badly. That helped me in designing the costumes for the Audio-Animatronics figures and for brassieres and girdles and such because I learned how the body worked and where the stresses came and so on. It really helped tremendously.

CS: Many women working in animation cite you as an inspiration.

Is it gratifying to see more women in the field today?

I’m very pleased to see women able to take jobs that they weren’t allowed to before. I would still love to see them make the same amount of money that men do for the same job. I think we’re still second-class citizens. We pay the same taxes and the same rent, we pay more for our clothes and we pay more to have our clothes cleaned, yet we’re paid less.

About Theme Park Press

Theme Park Press is the world's leading independent publisher of books about the Disney company, its history, its films and animation, and its theme parks. We make the happiest books on earth!

Our catalog includes guidebooks, memoirs, fiction, popular history, scholarly works, family favorites, and many other titles written by Disney Legends, Disney animators and artists, Mouseketeers, Cast Members, historians, academics, executives, prominent bloggers, and talented first-time authors.

We love chatting about what we do: drop us a line, any time.

Theme Park Press Books

The Unauthorized Story of Walt Disney's Haunted Mansion The Ride Delegate 501 Ways to Make the Most of Your Walt Disney World Vacation The Cotton Candy Road Trip The Wonderful World of Customer Service at Disney Disney Destinies Disney Melodies The Happiest Workplace on Earth Storm over the Bay A Historical Tour of Walt Disney World: Volume 1 Mouse in Transition Mouseketeers Down Under Murder in the Magic Kingdom Walt Disney and the Promise of Progress City Service with Character Son of Faster Cheaper A Tale of Two Resorts I Saw Ariel Do a Keg Stand The Adventures of Young Walt Disney Death in the Tragic Kingdom Two Girls and a Mouse Tale Ears & Bubbles The Easy Guide 2015 Who's the Leader of the Club? Disney's Hollywood Studios Funny Animals Life in the Mouse House The Book of Mouse Disney's Grand Tour The Accidental Mouseketeer The Vault of Walt: Volume 1 The Vault of Walt: Volume 2 The Vault of Walt: Volume 3 Who's Afraid of the Song of the South? Amber Earns Her Ears Ema Earns Her Ears Sara Earns Her Ears Katie Earns Her Ears Brittany Earns Her Ears Walt's People: Volume 1 Walt's People: Volume 2 Walt's People: Volume 13 Walt's People: Volume 14 Walt's People: Volume 15

Write for Theme Park Press

We're always in the market for new authors with great ideas. Or great authors with new ideas. Whichever type of author you are, we'd be happy to discuss your book. Before you contact us, however, please make sure you can answer "yes" to these threshold questions:

Is It Right for Us?

We specialize in books that have some connection to Disney or theme parks. Disney, of course, has become a broad topic, and encompasses not just theme parks and films but comic books, animation, and a big chunk of pop culture. Your book should fit into one (or more) of those broad categories.

Is It Going to Make Money?

There's never a guarantee that any book will make money, but certain types of books are less likely to do so than others. They include: hardcovers, books with color photos, and books that go on forever ("forever" as in 400+ pages). We won't automatically turn down these types of books, but you'll have to be a really good salesman to convince us.

Are You Great to Work With?

Writing books and publishing books should be fun. The last thing you want, and the last thing we want, is a contentious relationship. We work with authors who share our philosophy of no drama and zero attitude, and the desire for a respectful, realistic, mutually beneficial partnership.

If you said "yes" three times, please step inside.