- Visit the Imagineering Graveyard

- Now Sailing: "Skipper Stories" - Tales from the Jungle Cruise

- Coming Soon: The biography of Disney animator Jack Hannah

- Coming Soon: A Haunted Mansion anthology

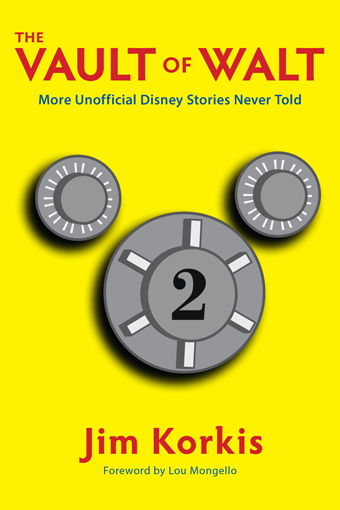

The Vault of Walt: Volume 2

More Unofficial Disney Stories Never Told

by Jim Korkis | Release Date: September 25, 2013 | Availability: Print, Kindle

Disney History at Its Best

No one knows Disney history, or tells it better, than Jim Korkis, and he’s back with a new set of 28 stories from his Vault of Walt. Whether it’s Disney films, Disney theme parks, or Walt himself, Jim’s stories will charm and delight Disney fans of all ages.

Korkis has been telling Disney storThe best-selling Vault of Walt series has brought serious, but fun, Disney history to tens of thousands of readers. Now in its second volume, the series features former Disney cast member and master storyteller Jim Korkis’ home-spun, entertaining tales, from the early years of Walt Disney to the present.

Step inside the vault with Jim to hear about:

- A ride through Epcot's Spaceship Earth for a closer look at graffiti, bare breasts, and evil twins

- The bare-knuckles battle between Walt Disney and P.L. Travers over Mary Poppins

- The real story of the Jungle Cruise, why Walt's plan for live animals was shot down, and how Walt once got cheated by an impatient skipper

- The life-long hatred between Walt and Bugs Bunny creator Friz Freleng caused by a boil on Freleng's butt

- How Roy O. Disney took over a demoralized company after his brother's death and built a fantasyland from swampland

Discover these and many other new tales of Disney history, as only Jim Korkis can tell them, in The Vault of Walt: Volume 2.

Then be sure to check ALL the volumes in The Vault of Walt!

Table of Contents

Foreword by Lou Mongello, host of WDW Radio

Introduction by Jim Korkis

Part One: Walt Disney Stories

Santa Walt

Walt and DeMolay

Return to Marceline 1956

Chicago Walt

Flying High with Walt

Walt and NASA

Cute Disney Story That Never Was

Part Two: Disney Film Stories

Toby Tyler

Lt. Robin Crusoe, U.S.N.

Blackbeard’s Ghost

The Shaggy Dog Story

Mary Poppins: Walt Disney vs P.L. Travers

Secrets of the Santa Cartoons

When Walt Laid a Golden Egg

Part Three: Disney Park Stories

The Partners Statue

The Story of Storybook Land

Inside Sleeping Beauty Castle

Secrets of Spaceship Earth 1982

EPCOT Fountain

Captain EO

The Birth of the Disneyland Jungle Cruise

Part Four: Other Disney Stories

Disneylandia

Disney Goes to Macy’s

Why Frank Lloyd Wright Hated Fantasia

Golden Oak Ranch

The Seven Snow Whites

The Friz and the Diz

Roy O. Disney: The Forgotten Brother Who Built a Magic Kingdom

Foreword

We are all cavemen.

Since the time when man was first able to communicate, stories have always brought people together. From gathering around the fire, to sharing tales in the written word, everyone loves to hear, tell, and share a good story.

Walt Disney was not simply a storyteller. He was THE storyteller. He knew not just the requisite elements that made up a good story, but how to tell it. Simple treatment of the tale, personalized antagonists, common moral ideals, and one’s struggles to test valor were the basic ingredients in all of his storytelling recipes. He told not just stories that people would remember but ones they would want to share with others.

Great storytellers are rare. Jim Korkis is one of them. Much like Walt Disney, Jim knows how to captivate a listener or reader through his passionate sharing of unique narratives. He has always embraced the importance of capturing these stories directly from the people who experienced them. But more important, he understands and is impassioned about sharing them with others…and he wants you, the Vault of Walt reader, to do the same.

The stories Jim has assembled in this book are ones that only Jim can weave…and told in only the way he can tell them. They come alive off the page, drawing you into them. He introduces you to a Walt Disney that you probably never knew before, all the while making you understand, appreciate, and see Walt in a new, wonderful light.

Walt Disney founded his studio based on the fundamentals of exceptional storytelling. Jim has done the same here in the Vault of Walt series. From details about Walt’s personal and private life, Jim paints a picture of Walt’s unique joys, struggles, and successes. Walt loved his family first and foremost, and Jim seamlessly takes you from Walt’s home during the holidays to his years spent in Chicago, to visiting his boyhood home with his brother Roy.

As we sit around this literary campfire listening to Jim, we learn more about the genesis of some famous films and theme park attractions. We are delighted and enlightened as we learn not only to understand and appreciate what we see and experience but to gain a greater fondness for the man who created them.

I distinctly and warmly remember the first time I met Jim, and how grateful I was for the mutual admiration, appreciation, and respect that we shared. More important, how that quickly grew into a friendship founded not simply on a love of Disney, but really more about a philosophy and set of ideals—ones that I believe were very much present in, and carried forward by, Walt Disney.

Walt’s work, wisdom, vision, and positivity have shaped many people, and his influence on Jim by virtue is apparent in the stories he shares in these pages. To that point, I also wonder if Walt knew…if he ever realized how what he was doing was more than simply making animated films or conjuring up attractions with pirates and friendly ghosts.How his belief in the importance of family would carry forward and impact the lives of millions. Or how he was helping people he never met, or who weren’t even born during his lifetime, to get the best out of themselves, by inspiring them to always keep moving forward.

And through the years, I’ve sat and listened to Jim tell stories around the fire in a variety of ways. From sitting across the table from him as we share a meal, to recording segments with him for my show, to reading his work online or in print, I have never stepped away feeling anything less than amazed. Jim has always enlightened me about some fact, detail, or personal anecdote that I had never heard before.

But it’s when he talks about Walt that his eyes (and mine…and I think as read this book, yours as well) widen and ignite. He speaks of Walt with such reverence, respect, and admiration, it’s as though he believes Walt just might be listening in. He speaks not only as a Disney historian but as that little boy who watched Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs for the very first time—mouth agape…the young man who sought out the artists and Imagineers at their homes to ask them to share (and allow him to record) their stories with him in person…and the adult who carries forward much of Walt’s spirit and philosophies—not just about storytelling, but about life, family, and what is truly important.

And so it took me some time to understand what Jim was really saying when he tells these stories (still wide-eyed and smiling through every one). He wants you to understand not just the importance of the story itself, but from where it came and why.He entrusts YOU to take these stories and share them with others. And I think most of all, The Vault of Walt series (which I hope continues ad infinitum) is in some ways Jim’s thank-you letter to Walt Disney.

So as Jim continues to thank Walt, we can thank Jim for bringing to light and life stories that only he can tell…in a way only he can share them. We are all cavemen…but Jim is among the most sincere, talented, and fascinating raconteurs of them all.

Thank you, Jim, for sharing these stories around the fire…

Introduction

Once upon a time, I wrote a book filled with stories about Walt Disney.

Some of the stories were specifically about Walt himself. Some were about films produced during his lifetime. Some were about Disneyland and Walt Disney World. And some were about Walt’s out-of-the-ordinary projects and the people who interacted with him.

The Vault of Walt was released in October 2010 and was warmly received by both reviewers and fans. I toured the United States doing presentations and book signings. I was happy to hear how much people enjoyed the stories, including Walt’s daughter, Diane Disney Miller.

It has been personally gratifying that no factual errors have been identified in the text since its first publication, rewarding my many decades of research.

However, new discoveries about the worlds of Disney are being made every day by passionate historians, and I have been fortunate to stumble across a few of them myself. Even with the plethora of fine books about Disney that have flooded the marketplace in the last three years, there are still many stories yet untold.

I grew up in Glendale, California, a city right next to Burbank, the home of the Disney studio.

My first grade teacher was Mrs. Margaret Disney, the second wife of Walt Disney’s older brother Herbert, who spent most of his life working for the U.S. Post Office.

She would sometimes complain that Walt only gave the two of them free tickets to Disneyland rather than some of that sizable fortune she imagined he must have accumulated. (Actually, Walt was broke until shortly before his death because he reinvested all the profits back into Disneyland and his films.)

When I learned of this Disney connection, I immediately took a large sheet of easel paper and drew a full-figure Jiminy Cricket, my favorite character at the time for a number of reasons, including that his first name was similar to what I was called, “Jimmy”. I also liked that Jiminy Cricket knew so much, as he demonstrated on segments of the original Mickey Mouse Club television show.

I proudly gave the drawing to Mrs. Disney in the hope she would rush to the Disney studio where, without a doubt, I would be instantly offered a job so I wouldn’t have to learn my multiplication tables (which I still do not know to this day). Apparently, portfolio review was backed up for a couple of decades, because I did not start working for the Disney Company officially until 1995.

At the age of twelve, I was enthralled by the weekly Disney television program, especially the episodes devoted to animation since I maintained hopes of becoming a cartoonist until I became a good enough artist to fully appreciate how bad I was and that I wouldn’t get much better.

Diligently, I scribbled down the names in the credits at the ends of those shows. I had no idea of the difference between an animator or a layout man or a special effects person.

I went to the Glendale-Burbank phone book (the cities were then small enough to have one book to cover them both), looked up the names I had written, and phoned them.

“I saw your name on the Disney TV show. How did you make things move?” I innocently but firmly inquired.

Eighty percent of the people I talked to were incredibly patient and kind and invited me over to watch them draw and listen to stories about working at Disney. About fifteen percent thought that it was some type of gag perpetrated by one of their work cronies, having a twelve year old phone up and say he liked the way they did cartoons. Five percent were wrong numbers.

So, for the next few years, I got to talk with Disney animators and Imagineers and write about it for my school newspaper, my local newspaper, and the Disney “fanzines” (non-professional magazines self-published by fans). In college, I wrote for professional magazines as well.

Fortunately, I took notes or recorded the conversations and transcribed them, because most of those wonderful folks who then seemed ancient to a teenager are no longer around to share their stories. In the last few years, I have felt an obligation and an urgency to tell those stories that never seem to appear elsewhere.

Some of those stories are in this book. Each chapter is a self-contained tale so feel free to read them in any order. In many cases, these stories fill in the gaps, the between-the-lines information, that for reasons of space or ignorance never appear in other books.

I am ecstatic that The Vault of Walt sold well enough that it allows me to offer more of these fabulous stories in a second volume. I’ve got many more stories to tell.

Jim Korkis

Jim Korkis is an internationally respected Disney historian who has written hundreds of articles about all things Disney for over three decades. He is also an award-winning teacher, a professional actor and magician, and the author of several books.

Korkis grew up in Glendale, California, right next to Burbank, the home of the Disney studios. As a teenager, Korkis got a chance to meet the Disney animators and Imagineers who lived nearby, and began writing about them for local newspapers.

In 1995, he relocated to Orlando, Florida, where he portrayed the character Prospector Pat in Frontierland at the Magic Kingdom, and Merlin the Magician for the Sword in the Stone ceremony in Fantasyland.

In 1996, Korkis became a full-time animation instructor at the Disney Institute teaching all of their animation classes, as well as those on animation history and improvisational acting techniques. As the Disney Institute re-organized, Jim joined Disney Adult Discoveries, the group that researched, wrote, and facilitated backstage tours and programs for Disney guests and Disneyana conventions.

Eventually, Korkis moved to Epcot as a Coordinator for the College and International Programs, and then as a Coordinator for the Epcot Disney Learning Center. He researched, wrote, and facilitated over two hundred different presentations on Disney history for Cast Members and for such Disney corporate clients as Feld Entertainment, Kodak, Blue Cross, Toys “R” Us, and Military Sales.

Korkis has also been the off-camera announcer for the syndicated television series Secrets of the Animal Kingdom; has written articles for several Disney publications, including Disney Adventures, Disney Files (DVC), Sketches, and Disney Insider; and has worked on many different special projects for the Disney Company.

In 2004, Disney awarded Jim Korkis its prestigious Partners in Excellence award.

A Chat with Jim Korkis

If you have a question for Jim Korkis that you would like to see answered here, please get in touch and let us know what's on your mind.

You began exceptionally early as a Disney historian. You were how old?

I was about 15 when I interviewed Jack Hannah with my little tape recorder and school notebook with questions printed neatly in ink. I learned to develop a very good memory because often when the tape recorder was running, people would freeze up. So, I sometimes turned off the tape recorder and just took notes which I later verified with the person. I always gave them a chance to review what they had said and make any changes. I lost a lot of great stories, although I still have them in my files for future generations, but gained a lot of trust.

How were able to hook up with these guys

I was very, very lucky. I was a kid, and it never occurred to me that when I saw their names in the end credits of the weekly Disney television show that I couldn't just find their names in the local phone book and call them up. Ninety percent of them were gracious, but there were about ten percent who thought it was a joke and that maybe one of their friends had put me up to phoning them.

It was like dominoes. Once I did one interview and the person was pleased, he put me in touch with others. After some of those interviews were published in my school paper and local newspapers, it gave me some greater credibility. Later, when they started to appear in magazines, I got even more opportunities.

How do you conduct your research?

JIM: You know, one of the proudest things for me about my books is that not a single factual error has been found.

To do my research, I start with all the interviews I've done over the past three decades, some of which are some available in the Walt's People series of books edited by Didier Ghezz. When necessary, I contact other Disney historians and authorities to fill in the gaps. And I have amassed a huge library of books, magazines, and documents.

When I moved from California to Florida, I brought with me over 20,000 pounds of Disney research material. The moving company that had just charged me a flat fee was shocked they had so severely underestimated the weight, and lost thousands of dollars. That was over fifteen years ago and the collection has only grown since that time.

About The Vault of Walt Series

You've been writing articles and columns about Disney for decades. Why all of a sudden start writing Vault of Walt books?

JIM: I was fortunate to grow up in the Los Angeles area at a time when I had access to some of Walt’s original animators and Imagineers. They shared with me some wonderful stories. I wrote articles about their for various magazines and “fanzines” of the time. All of those publications are long gone and often difficult to find today.

As more and more of Walt’s “original cast” pass away, I realized that their stories had not been properly documented, and that unless I did something, they would be lost. Everyone always told me I should write a book telling these tales and finally I decided to do it.

Walt's daughter Diane Disney Miller wrote the foreword to your first book. How did that come about?

JIM: She actually contacted me. Her son, Walter, loved the Disney history columns and articles I was writing and would send them to her. I was overwhelmed that she enjoyed them. She was appreciative that I tried to treat her dad fairly and not try to psycho-analyze why he did what he did.

She also liked that I revealed things she never knew about her father. As we talked and I told her I was doing the book, I asked if she would write the foreword. She agreed immediately and I had it within a week. She even invited me to go to the Disney Family Museum in San Francisco and give a presentation. She is an incredible woman.

What was Diane's favorite story in the book?

JIM: Obviously, the ones about her dad were a big hit. She especially liked the chapter about Walt and his feelings toward religion. She told me that it accurately reflected how she saw her dad act.

What's your favorite story in the book?

JIM: That’s like asking a parent to pick their favorite child. I tried to put in all the stories I loved because I figured this might be the only book about Disney I would ever write.

One chapter that I have grown to love even more since it was first published is the one about Walt’s love of miniatures. I recently found more information about that subject, and then on the trip to Disney Family Museum, I was able to spend hours examining some of Walt’s collection up close.

About Who's Afraid of the Song of the South?

Why did you decide to write a book about Song of the South?

JIM: I wanted to read a “Making of the Song of the South” book, but nobody else was ever going to write it. I wanted to know the history behind the production, why Walt made certain choices, and as many behind-the-scenes tidbits that could be told. I didn’t want to read a sociological thesis on racism.

Fortunately, over the years I had interviewed some of the people involved in the production, had seen the film multiple times, and had gathered material from pressbooks to newspaper articles to radio shows of the era.

There are a lot of misconceptions about Song of the South. I wanted to get the facts in print and let people make up their own minds.

Did you learn anything new when writing the book?

JIM: I thought I knew a lot after being actively involved in Disney history for over three decades, but writing this book showed me how little I really know.

For example, I learned that it was Clarence Nash, the voice of Donald Duck for decades, who did the whistling for Mr. Bluebird on Uncle Remus’ shoulder. I learned that Ward Kimball used to host meetings of UFO enthusiasts at his home. I learned that the Disney Company tried for years to make a John Carter of Mars feature. I learned that Walt himself tried to make a sequel to The Wizard of Oz. I learned that Disney operated a secret studio to make animated television commercials in the mid-1950s to raise money to build Disneyland. And so much more.

Even the most knowledgeable Disney fans will find new treasures of information on every page of this book.

What's the biggest takeaway from the book?

JIM: Walt Disney was not racist. That is one of those urban myths which popped up long after Walt died, and so he was unable to defend himself.

In my book, I make it clear that Walt had no racist intent at all in making Song of the South. He merely wanted to share the famous Uncle Remus stories that he enjoyed as a child, and he treated the black cast with respect and generosity.

Many people don't realize that the events in the film take place after the Civil War, during the Reconstruction. So many offensive Hollywood films made at the same time as Song of the South, even one with little Shirley Temple, depicted the Old South during the Civil War in an unrealistic manner. Walt's film got lumped in with them, and he was a visible target for a much larger crusade.

Books by Jim Korkis:

- The Vault of Walt: Volume 3 (2014)

- Animation Anecdotes: The Hidden History of Classic American Animation (2014)

- Who's the Leader of the Club? Walt Disney's Leadership Lessons (2014)

- The Book of Mouse: A Celebration of Walt Disney's Mickey Mouse (2013)

- Who's Afraid of the Song of the South? And Other Forbidden Disney Stories (2012)

- The Vault of Walt: Volume 2 (2013)

- The Vault of Walt: Volume 1 (2012)

With John Cawley:

- Animation Art: Buyer's Guide and Price Guide (1992)

- Cartoon Confidential (1991)

- How to Create Animation (1991)

- The Encyclopedia of Cartoon Superstars: From A to (Almost) Z (1990)

In this excerpt, from "Disney Film Stories", Jim gives the blow-by-blow account of the animosity between Walt Disney and P.L. Travers over their clashing visions for Mary Poppins.

The first time P.L. Travers saw the Disney film version of Mary Poppins was at the Hollywood premiere to benefit the California Institute of the Arts on Thursday, August 27, 1964, at Grauman’s Chinese Theater in Hollywood.

She had not been invited.

One of her lawyers, Diarmuid Russell, and her American publisher (Harcourt, Brace & World), had asked for her to be invited but had been ignored by the Disney studio.

Travers sent a telegram to Walt telling him that she was coming to Hollywood for the premiere and was sure that somebody would be able to find an extra seat for her somewhere. If it were not too much trouble, she continued, could Walt please let her know the details of time and place.

Disney story editor Bill Dover, who had been Travers’ “babysitter” when she visited the Disney studio in 1962, responded almost immediately that a formal invitation was in the mail and offered to escort her to the premiere. This was followed by a message from Walt stating that while he had counted on her presence at the London premiere he was happy she could attend the one in Hollywood.

Harcourt, Brace & World paid for her flight to Los Angeles (on August 26) and for a three-day stay at the Beverly Wilshire Hotel.

Travers arrived in a long white satin gown with long gloves. While there are a handful of photos of Walt posing with Travers, he spent very little time with her at the premiere.

During the film, Travers cried. Some observers felt that her tears were of happiness at seeing her creation on the screen in such an outstanding film. Cynics suggested the tears were of joy that the film was such a success she would be financially stable for the rest of her life because of the percentage she would receive. Travers claimed they were bitter tears: "Tears ran on my cheeks because it was all so distorted… I was so shocked that I felt I would never write, let alone smile, again!"

On the huge screen her name was in small type and her role described vaguely as “consultant”, with the film “Based on the stories by P. L. Travers”. She realized that from now on it would be “Walt Disney’s Mary Poppins” just as his versions of other novels had usurped writers like James Barrie, Lewis Carroll, and others.

Later, she wrote that the credit should have been “P.L. Travers’s Mary Poppins, screened by Walt Disney”.

At the after-party hosted by Technicolor in a nearby parking lot themed to an English garden with weeping willows and strolling performers, Richard Sherman recalled Travers approaching Walt and saying in a loud voice, “Well, the first thing that has to go is the animation sequence.”

Calmly and coolly, Walt responded, “Pamela, that ship has sailed.”

While Travers had approval of the script, once the film was made it belonged entirely to Disney. He walked away to greet some of the many well-wishers. Travers not only hated the animation sequence but, in particular, as she told a writer for Ladies’ Home Journal, the animated horse and pig.

The next day, she sent a telegram to Walt congratulating him on the cast and the picture, and for keeping true to the spirit of Mary Poppins. She kept a copy of the telegram and annotated it with the comment that there was so much she wasn’t able to say at the time so that posterity might know her true feelings.

Walt replied formally that he was happy for her reaction and it was a pity that “the hectic activities before, during and after the premiere” meant that they had little time to spend together.

Travers replied that the premiere was wonderful, but that the real Mary Poppins remained within the covers of her books and she hoped the success of the film would turn a new audience into readers of those books. She kept a copy of that letter as well, annotating it with the remark that there was “much between the lines” she wasn’t able to say at the time.

In a September 2, 1964, letter to her publisher, she wrote that the film was: “…Disney through and through, spectacular, colourful, gorgeous but all wrapped around mediocrity of thought, poor glimmerings of understanding”.

Back in New York, Travers attended the film’s premiere at Radio City Music Hall in September and gave interviews, concentrating on her books. With the success of the movie, sales of her books tripled, though the books that featured the Disney version of the story outsold hers by five to one.

Later, she would tell an interviewer (and then insist the remark was not for publication) that the “movie hasn’t simplicity, it has simplification.”

As the years passed, Travers became more and more adamant that she did not want to be remembered by the movie version of Mary Poppins and that it was all fantasy but no magic. The “Royal European” premiere of Mary Poppins was held at the Leicester Square Theater on December 17, 1964. Travers was in attendance as was Princess Margaret and Lord Snowdon. Walt did not attend.

In 1987, there were plans for P.L. Travers (with the assistance of Disney historian Brian Sibley) to write the treatment for a sequel to the film.

The Disney studio had proposed a sequel where Julie Andrews would return as Mary Poppins to help the children of the grown-up Michael and Jane Banks. Of course, Travers instantly found such a proposal completely unacceptable, but Sibley convinced her to consider writing a treatment so that Mary Poppins could be presented the way she wanted. Sibley then wrote to Roy E. Disney, who immediately agreed to do whatever Travers wished. When Jeffrey Katzenberg met with Sibley and Travers in the United Kingdom, she laid out her demands for how the character was to be portrayed.

Sibley and Travers viewed the film in Disney’s London office since Travers had not seen it since its premiere over twenty years earlier. Sibley was surprised by how much Travers, in between her predictable, repeated complaints, liked parts of the film, and told him to make notes of those moments for possible inclusion in the treatment.

By mid-1988, Sibley was hard at work on the screenplay for Mary Poppins Comes Back. It would not only be a sequel to the Disney film (utilizing some of the original elements introduced in that film) but also include “adventures drawn from stories in the original books”.

In the treatment, Mrs. Banks had given birth to twins, given up the cause of women’s suffrage, and was giving emotional support to her husband whose new position at the bank was causing him concern over the imprudent investments that have brought the bank serious financial difficulties.

A new nanny has been impossible to find for the children, Jane and Michael, who are in the park having problems with their kite. They are helped by Barney, the ice cream man.

Barney is the Cockney younger brother of Bert, who has moved on to cleaning the chimneys of the rich and famous. Like Bert, Barney is a jack-of-all-trades though merely a non-magical friend of Mary Poppins. The Disney studio had suggested having a different character than Bert and later suggested singer Michael Jackson for the role. Jackson, who was not only immensely popular at the time, had just completed the Captain EO project and was considered “part of the Disney [studio] family”.As the children reel in their kite, Mary Poppins is at the other end. Adventures ensue, including the use of a magic compass for an around-the-world trip that had been originally planned for the first film but not used. Many of Mary Poppins’ relatives make appropriate appearances, and there is a significant emphasis on the importance of memories as well as the fact that it is music and not money that makes the world go round.

Sibley worked on two versions of the screenplay. Disney, as was its way, brought on two other screenwriters, Perry and Randy Howze (who had written the 1988 Disney movie, Mystic Pizza) to take a shot at it, but eventually shelved the project.

In 1989, Travers decided to sell her papers to a major American collection. Since the correspondence included her annotated carbons of letters to Walt Disney, she hoped that posterity would see her genuine response to the Disney film and how the company had ignored her obviously perceptive objections.

There were no interested buyers, and so the collection of twenty-eight manuscript boxes were repackaged and sold to the Mitchell Library, part of the State Library of New South Wales, in Sydney, Australia, roughly eighty miles from where Travers was raised by her mother.

As one of her final acts, she gave permission for the development of a theatrical musical production of Mary Poppins but only with the stipulation that no Americans be involved with it and, in particular, no one connected with the film. That meant the Sherman Brothers, who were still alive and writing songs, could not contribute new tunes to the production.

When Travers passed away in 1996, the Disney Company took out the standard advertisement in the Hollywood trade magazines showing an image of a crying Mickey Mouse. They also became involved in the theatrical production.

The checks from Disney kept rolling in year after year, not just for the re-release of the film or its many home video versions, but for related things like arena theater productions that featured the characters, merchandise, and more. Her connection with Disney made Travers an incredibly wealthy woman for the rest of her life.

Despite that, shortly before her death she wrote: “How much better a film would it have been had it carefully stayed with the true version of Mary Poppins.”

When she would complain to her lawyer, Arnold Goodman, about how Disney had “tricked her” and mutilated her books, he reminded her: “You should repeat three times nightly—before and after prayer… 'But for dear Mr. Goodman, I would never have sold Mary Poppins to Walt Disney and would not now be rich.'”

About Theme Park Press

Theme Park Press is the world's leading independent publisher of books about the Disney company, its history, its films and animation, and its theme parks. We make the happiest books on earth!

Our catalog includes guidebooks, memoirs, fiction, popular history, scholarly works, family favorites, and many other titles written by Disney Legends, Disney animators and artists, Mouseketeers, Cast Members, historians, academics, executives, prominent bloggers, and talented first-time authors.

We love chatting about what we do: drop us a line, any time.

Theme Park Press Books

The Unauthorized Story of Walt Disney's Haunted Mansion The Ride Delegate 501 Ways to Make the Most of Your Walt Disney World Vacation The Cotton Candy Road Trip The Wonderful World of Customer Service at Disney Disney Destinies Disney Melodies The Happiest Workplace on Earth Storm over the Bay A Historical Tour of Walt Disney World: Volume 1 Mouse in Transition Mouseketeers Down Under Murder in the Magic Kingdom Walt Disney and the Promise of Progress City Service with Character Son of Faster Cheaper A Tale of Two Resorts I Saw Ariel Do a Keg Stand The Adventures of Young Walt Disney Death in the Tragic Kingdom Two Girls and a Mouse Tale Ears & Bubbles The Easy Guide 2015 Who's the Leader of the Club? Disney's Hollywood Studios Funny Animals Life in the Mouse House The Book of Mouse Disney's Grand Tour The Accidental Mouseketeer The Vault of Walt: Volume 1 The Vault of Walt: Volume 2 The Vault of Walt: Volume 3 Who's Afraid of the Song of the South? Amber Earns Her Ears Ema Earns Her Ears Sara Earns Her Ears Katie Earns Her Ears Brittany Earns Her Ears Walt's People: Volume 1 Walt's People: Volume 2 Walt's People: Volume 13 Walt's People: Volume 14 Walt's People: Volume 15

Write for Theme Park Press

We're always in the market for new authors with great ideas. Or great authors with new ideas. Whichever type of author you are, we'd be happy to discuss your book. Before you contact us, however, please make sure you can answer "yes" to these threshold questions:

Is It Right for Us?

We specialize in books that have some connection to Disney or theme parks. Disney, of course, has become a broad topic, and encompasses not just theme parks and films but comic books, animation, and a big chunk of pop culture. Your book should fit into one (or more) of those broad categories.

Is It Going to Make Money?

There's never a guarantee that any book will make money, but certain types of books are less likely to do so than others. They include: hardcovers, books with color photos, and books that go on forever ("forever" as in 400+ pages). We won't automatically turn down these types of books, but you'll have to be a really good salesman to convince us.

Are You Great to Work With?

Writing books and publishing books should be fun. The last thing you want, and the last thing we want, is a contentious relationship. We work with authors who share our philosophy of no drama and zero attitude, and the desire for a respectful, realistic, mutually beneficial partnership.

If you said "yes" three times, please step inside.