- Visit the Imagineering Graveyard

- Now Sailing: "Skipper Stories" - Tales from the Jungle Cruise

- Coming Soon: The biography of Disney animator Jack Hannah

- Coming Soon: A Haunted Mansion anthology

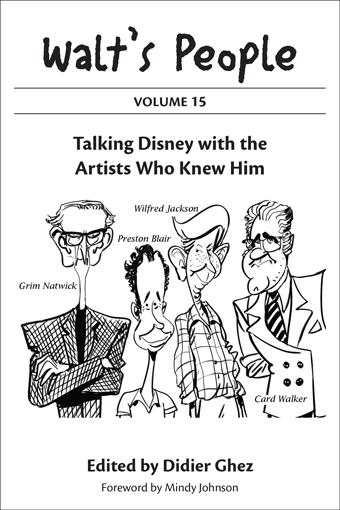

Walt's People: Volume 15

Talking Disney with the Artists Who Knew Him

by Didier Ghez | Release Date: November 8, 2014 | Availability: Print, Kindle

Disney History from the Source

The Walt's People series is an oral history of all things Disney, as told by the artists, animators, designers, engineers, and executives who made it happen, from the 1920s through the present.

Walt’s People: Volume 15 features appearances by Robert Cook, Grim Natwick, Clair Weeks, Willis Pyle, Charlene Sundblad (about Helen and Hugh Hennesy), Preston Blair, Lynn Karp, Ward Kimball, Wilfred Jackson, Hamilton Luske (remembered by his children), Norman "Stormy" Palmer, Guy Williams Jr., Buddy Van Horn, Suzanne Lloyd, Karl Bacon and Ed Morgan, Bill Martin, Bill Evans, Card Walker, and Mike Peraza, plus an article by Steven Hartley about Cy Young and one about Riley Thomson by Alberto Becattini.

Among the hundreds of stories in this volume:

- BILL EVANS explains how he used his green thumb for decades to design and cultivate the beautiful, diverse displays of plants, trees, and flowers without which Disneyland and Walt Disney World would be just so much concrete.

- BOB COOK provides insight into the little-known world of Disney sound engineer, a role he filled from his first day with the Disney Studio in 1930 through his retirement over forty years later in 1971.

- MIKE PERAZA went to work for Disney during its period of transition from Walt to corporate honchos like Michael Eisner. He recalls what it was like to be an animator in a studio that was changing what it meant to be an animator.

The entertaining, informative stories in every volume of Walt's People will please both Disney scholars and eager fans alike.

Table of Contents

Foreword

Introduction

Robert Cook by Dave Smith

Grim Natwick by John Culhane

Clair Weeks by Milton Gray

Willis Pyle by Bob Casino

Charlene Sundblad about Helen and Hugh Hennesy by Didier Ghez

Preston Blair by Goran Broling

Working on "The Sorceror's Apprentice" by Preston Blair

The Life and Times of Cy Young by Steven Hartley

Lynn Karp by Michael Barrier and Milton Gray

Of Skit and Skat and This and That: The Autobiography of Basil Reynolds by Basil Reynolds

The Life and Times of Riley Thomson by Albert Becattini

Ward Kimball by John Culhane

Wilfred Jackson by John Culhane

Hamilton Luske remembered by his children, Carol Jean Luske, Peggy Finefrock, and Jim Luske by Jim Korkis

Norman “Stormy” Palmer by Michael Broggie

Guy Williams by EMC West

Buddy Van Horn by EMC West

Suzanne Lloyd by EMC West

Draft of Biographical Notes on Roger Broggie by George Sherman

Karl Bacon and Ed Morgan by Jim Korkis

Bill Martin by Dave Smith

Bill Evans by Jay Horan

Card Walker by John Culhane

Mike Peraza by Didier Ghez

Further Reading

Foreword

I’ve always been curious about…curiosity. What exactly is this thing that compels us to explore, to unearth, to discover whatever the cost or outcome? The notion of being “curious” implies general inquisitiveness, yet this simple word often carries a negative connotation, especially in today’s media-driven society where we focus on a less commendable side to curiosity.

Most interpretations of the word are defined as “a desire to know about people or things that do not concern one”, or “nosiness”. As an inquisitive child, I often heard the phrase “curiosity killed the cat”, no doubt the careful warning of a weary parent or well-intentioned teacher. This caution seemed reasonable, since we can never fully know the consequences, variables, or final outcomes when we begin to follow our desires for certain knowledge. All throughout history, great minds have reflected on the pitfalls of curiosity. As early as 397 AD, Saint Augustine noted: “God fashioned hell for the inquisitive.” Oscar Wilde timelessly observed, “The public have an insatiable curiosity to know everything, except what is worth knowing.” Even Dorothy Parker, reflecting on her life as a woman ahead of her time, winked: “Four be the things I’d been better without: Love, curiosity, freckles and doubt.”

Fortunately, time and experience teach that there is another side to the coin of curiosity: The simple “desire to know or to learn”. Eleanor Roosevelt declared: “I think, at a child’s birth, if a mother could ask a fairy godmother to endow it with the most useful gift, that gift would be curiosity”. Lewis Carroll signaled Alice’s grand adventure in Wonderland with the very words “Curiouser and curiouser.” And for Walt Disney, it was simply inherent: “I’m just very curious—got to find out what makes things tick.”

This insatiable desire to know and understand is an active thing. It prods us on to explore, and discover, often leading to more questions than answers, but that’s the magic of curiosity. It’s a call to adventure, the catalyst that arouses and compels us to begin the journey. It causes us to dig deep until what is unknown is fully known. Just as pieces of a puzzle come together to reveal the completed picture, the same is true of information. As one discovery leads to another, the dots begin to connect and the answers become clear. It was this intrinsic curiosity that marked the cornerstone of Walt Disney’s Studio:

Since my outlook and attitudes are ingrained throughout our organization, all our people have this curiosity; it keeps us moving forward, exploring, experimenting, opening new doors. And curiosity keeps leading us down new paths.

In this latest volume of Walt’s People, Disney’s forward-thinking legacy continues through the power of curiosity. It caused you, the reader, to open this book. Your curious mind is here to discover (through these interviews and conversations, conducted and carefully compiled by other curious minds) a new understanding into the experiences and accomplishments of other extraordinary people who shared Walt’s curiosity, and achieved magic. The insights and findings within these pages—roiling in your curious mind—perpetuate this inquisitiveness, guiding you onto new explorations, discoveries, and inspirations. Your work will then open new doors, leading other curious minds down similar paths of exciting discoveries to their own magic, and so on.

Powerful, infectious, and vital, curiosity places you on the threshold of limitless possibilities. Walt Disney, and those who worked with him, understood this. Thankfully, his legacy of curiosity and discovery lives on in these interviews, and in the curious minds of others, like yours!

And for those who side with caution, it turns out it wasn’t “curiosity” that brought about the unfortunate demise of the cat after all. The first use of this adage dates back to the mid-16th century. In his comedy Much Ado About Nothing, William Shakespeare crafted the phrase: “Care killed a cat”, cautioning against over-anxiety leading to an early grave. It was Eugene O’Neil, in a 1921 play, who first associated “curiosity” with what “killed the cat”, to which he aptly added: “but satisfaction brought it back”.

So, “satisfy” your “curiosity” by turning the page and let a new adventure begin!

Introduction

Who did what? Who worked with whom? Who were they? These are some of the most important questions today when it comes to Disney history.

What did an individual artist do on each specific project? The answer is fairly easy when you are discussing the top animators; it isn’t so obvious when one focuses on the storymen or the concept artists.

Who were the artists who worked together and on which project? Again, not always an easy question to answer. We knew that storyman Homer Brightman was often paired up with Harry Reeves, but until we read his autobiography, Life in the Mouse House (Theme Park Press), we had no idea that Frenchy de Trémaudan had also been his teammate.

Who were the artists who worked for Walt? How did each one get recruited? What were their individual styles? Who were they as human beings and artists? What were their individual stories? All these questions are central to the new understanding of Disney history, pioneered by the likes of Christopher Finch, Michael Barrier, JB Kaufman, and John Canemaker. The contributors and readers of the Walt’s People series are well aware of them.

A few months ago, I had the pleasure of starting work on a series of art books, which will be released by Chronicle Books, and which focus on the life, art, and careers of Disney’s concept artists. The first volume will feature Albert Hurter, Ferdinand Horvath, Gustaf Tenggren, and Bianca Majolie. Interestingly, as had happened in the case of Disney’s Grand Tour and the Walt’s People book series, methodically focusing on a specific subject allowed me to unearth exceptionally interesting new documents: Never-seen-before artwork by and information about Johnny Walbridge; new information about Retta Scott’s career; or the lost diaries of Ferdinand Horvath, which document his life and career day by day, almost minute by minute.

Once again my old advice remains: If you want to contribute meaningfully to Disney history research and make interesting discoveries, choose a subject that you love, read everything that has already been written about it, check all the sources of the information, look for the gaps, follow every available lead, and always “dig deeper” until you hit rock bottom. That’s the very same feeling I experienced when I first read Dave Smith’s exceptional interview with Bob Cook, one of Walt’s first sound engineers. By doing so, you will soon share the exhilarating feeling of uncovering new Disney history treasures.

Didier Ghez

Didier Ghez has conducted Disney research since he was a teenager in the mid-1980s. His articles about the Disney parks, Disney animation, and vintage international Disneyana, as well as his many interviews with Disney artists, have appeared in Animation Journal, Animation Magazine, Disney Twenty-Three, Persistence of Vision, StoryboarD, and Tomart’s Disneyana Update. He is the co-author of Disneyland Paris: From Sketch to Reality, runs the Disney History blog, the Disney Books Network, and serves as managing editor of the Walt’s People book series.

A Chat with Didier Ghez

If you have a question for Didier that you would like to see answered here, please get in touch and let us know what's on your mind.

About The Walt's People Series

How did you get the idea for the Walt's People series?

GHEZ: The Walt’s People project was born out of an email conversation I conducted with Disney historian Jim Korkis in 2004. The Disney history magazine Persistence of Vision had not been published for years, The “E” Ticket magazine’s future was uncertain, and, of course, the grandfather of them all, Funnyworld, had passed away 20 years ago. As a result, access to serious Disney history was becoming harder that it had ever been.

The most frustrating part of this situation was that both Jim and I knew huge amounts of amazing material was sleeping in the cabinets of serious Disney historians, unavailable to others because no one would publish it. Some would surface from time to time in a book released by Disney Editions, some in a fanzine or on a website, but this seemed to happen less and less often. And what did surface was only the tip of the iceberg: Paul F. Anderson alone conducted more than 250 interviews over the years with Disney artists, most of whom are no longer with us today.

Jim had conceived the idea of a book originally called Talking Disney that would collect his best interviews with Disney artists. He suggested this to several publishers, but they all turned him down. They thought the potential market too small.

Jim’s idea, however, awakened long forgotten dreams, dreams that I had of becoming a publisher of Disney history books. By doing some research on the web I realized that new "print-on-demand" technology now allowed these dreams to become reality. This is how the project started.

Twelve volumes of Walt's People later, I decided to switch from print-on-demand to an established publisher, Theme Park Press, and am happy to say that Theme Park Press will soon re-release the earlier volumes, removing the few typos that they contain and improving the overall layout of the series.

How do you locate and acquire the interviews and articles?

To locate them, I usually check carefully the footnotes as well as the acknowledgments in other Disney history books, then get in touch with their authors. Also, I stay in touch with a network of Disney historians and researchers, and so I become aware of newly found documents, such as lost autobiographies, correspondence with Disney artists, and so forth, as soon as they've been discovered.

Were any of them difficult to obtain? Anecdotes about the process?

Yes, some interviews and autobiographical documents are extremely difficult to obtain. Many are only available on tapes and have to be transcribed (thanks to a network of volunteers without whom Walt’s People would not exist), which is a long and painstaking process. Some, like the seminal interview with Disney comic artist Paul Murry, took me years to obtain because even person who had originally conducted the interview could not find the tapes. But I am patient and persistent, and if there is a way to get the interview, I will try to get it, even if it takes years to do so.

One funny anecdote involves the autobiography of the Head of Disney’s Character Merchandising from the '40s to the '70s, O.B. Johnston. Nobody knew that his autobiography existed until I found a reference to an article Johnston had written for a Japanese magazine. The article was in Japanese. I managed to get a copy (which I could not read, of course) but by following the thread, I realized that it was an extract from Johnston’s autobiography, which had been written in English and was preserved by UCLA as part of the Walter Lantz Collection. (Later in his career Johnston had worked with Woody Woodpecker’s creator.) Unfortunately, UCLA did not allow anyone to make copies of the manuscript. By posting a note on the Disney History blog a few weeks later, I was lucky enough to be contacted by a friend of Johnston's family, who lives in England and who had a copy of the manuscript. This document will be included in a book, Roy's People, that will focus on the people who worked for Walt's brother Roy.

How many more volumes do you foresee?

That is a tough question. The more volumes I release, the more I find outstanding interviews that should be made public, not to mention the interviews that I and a few others continue to conduct on an ongoing basis. I will need at least another 15 to 17 volumes to get most of the interviews in print.

About Disney's Grand Tour

You say that you've worked on this book for 25 years. Why so long?

DIDIER: The research took me close to 25 years. The actual writing took two-and-a-half years.

The official history of Disney in Europe seemed to start after World War II. We all knew about the various Disney magazines which existed in the Old World in the '30s, and we knew about the highly-prized, pre-World War II collectibles. That was about it. The rest of the story was not even sketchy: it remained a complete mystery. For a Disney historian born and raised in Paris this was highly unsatisfactory. I wanted to understand much more: How did it all start? Who were the men and women who helped establish and grow Disney's presence in Europe? How many were they? Were there any talented artists among them? And so forth.

I managed to chip away at the brick wall, by learning about the existence of Disney's first representative in Europe, William Banks Levy; by learning the name George Kamen; and by piecing together the story of some of the early Disney licensees. This was still highly unsatisfactory. We had never seen a photo of Bill Levy, there was little that we knew about George Kamen's career, and the overall picture simply was not there.

Then, in July 2011, Diane Disney Miller, Walt Disney's daughter, asked me a seemingly simple question: "Do you know if any photos were taken during the 'League of Nations' event that my father attended during his trip to Paris in 1935?" And the solution to the great Disney European mystery started to unravel. This "simple" question from Diane proved to be anything but. It also allowed me to focus on an event, Walt's visit to Europe in 1935, which gave me the key to the mysteries I had been investigating for twenty-three years. Remarkably, in just two years most of the answers were found.

Will Disney's Grand Tour interest casual Disney fans?

DIDIER: Yes, I believe that casual readers, not just Disney historians, will find it a fun read. The book is heavily illustrated. We travel with Walt and his family. We see what they see and enjoy what they enjoy. And the book is full of quotes from the people who were there: Roy and Edna Disney, of course, but also many of the celebrities and interesting individuals that the Disneys met during the trip. And on top of all of this, there is the historical detective work, that I believe is quite fun: the mysteries explored in the book unravel step by step, and it is often like reading a historical novel mixed with a detective story, although the book is strict non-fiction.

Walt bought hundreds of books in Europe and had them shipped back to the studio library. Were they of any practical use?

DIDIER: Those books provided massive new sources of inspiration to the Story Department. "Some of those little books which I brought back with me from Europe," Walt remarked in a memo dated December 23, 1935, "have very fascinating illustrations of little peoples, bees, and small insects who live in mushrooms, pumpkins, etc. This quaint atmosphere fascinates me."

What other little-known events in Walt's life are ripe for analysis?

DIDIER: There are still a million events in Walt's life and career which need to be explored in detail. To name a few:

- Disney during WWII (Disney historian Paul F. Anderson is working on this)

- Disney and Space (I am hoping to tackle that project very soon)

- The 1941 Disney studio strike

- Walt's later trips to Europe

The list goes on almost forever.

Other Books by Didier Ghez:

- They Drew as They Pleased: The Hidden Art of Disney's Golden Age (2015)

- Disney's Grand Tour: Walt and Roy's European Vacation, Summer 1935 (2013)

- Disneyland Paris: From Sketch to Reality (2002)

Didier Ghez has edited:

- Walt's People: Volume 15 (2014)

- Walt's People: Volume 14 (2014)

- Walt's People: Volume 13 (2013)

- Walt's People: Volume 12 (20xx)

- Walt's People: Volume 11 (20xx)

- Walt's People: Volume 10 (20xx)

- Walt's People: Volume 9 (20xx)

- Walt's People: Volume 8 (20xx)

- Walt's People: Volume 7 (20xx)

- Walt's People: Volume 6 (20xx)

- Walt's People: Volume 5 (20xx)

- Walt's People: Volume 4 (20xx)

- Walt's People: Volume 3 (2015)

- Walt's People: Volume 2 (2015)

- Walt's People: Volume 1 (2014)

- Life in the Mouse House: Memoir of a Disney Story Artist (2014)

- Inside the Whimsy Works: My Life with Walt Disney Productions (2014)

In this excerpt, Disney Legend Ward Kimball tells interviewer John Culhane about Riley Thomson's sadistic sense of humor and Art Babbitt's sexual prowess.

John Culhane: I don’t know why you’re so un-fond of Nifty Nineties.

WARD KIMBALL: Oh, jeez, that’s terrible.

JC: Do you think?

I thought it was terrible when I was doing it. I wish I’d never even done it. First of all, it shouldn’t have been made into a picture, and Riley Thomson was no director. There was no system in the picture, it was a hit-and-miss thing. Riley would do such things like: Bud Swift had a scene where a horse makes a tap and goes up out of the scene, and you cut to him later, because Mickey’s car comes by and he’s looking like this. [Gestures] Just for a gag, he made Bud do that over eight times. And really nothing was wrong with the first one. But that was Riley’s sense of humor. It was his own picture, and this was sort of a hazing thing.

JC: He was a sadist.

Yeah, right. Riley was responsible for the famous five-gallon jug of cross-dissolve liquid. Any new guy that would come in there to the studio, they’d start them out in the Traffic Department. If he didn’t quite like him—there could be little things, like if they were Jewish, for instance—he would call them up and say that he had a delivery to make, and the kid, the poor kid would come up there, and Riley had this big Sparkles water bottle filled with water, where he’d dump a little ink in it, turn it grey, and there’d be a big label on it, “Cross Dissolve Liquid”, and all this official printing on it. He’d say, “Deliver this over to the Animation Building, or sound stage, to so-and-so…” He’d deliver it and have a hard time finding… He’s lugging this heavy bottle, when he’d find the person, and they’d say, “Oh, no, that’s supposed to go to Ward Kimball up in…” You know, this thing would go on and on, and this kid would spend the whole first day lugging this five-gallon bottle. That was Riley’s idea of a joke.

JC: That’s a good story, though.

And that’s why that goddamn picture is no good.

JC: That’s a good story! One of the cartoons I love to show is Ferdinand the Bull, and it’s a big boot always to see all those bullfighters come out and [to be able to] say, “That’s Ward Kimball, that’s Bill Tytla, that’s—”

That’s Art Babbitt, Bill Tytla, Ham Luske, and Fred Moore.

JC: I said to Babbitt one time, “Why did they caricature you with a big ass sticking out like that?” And Babbitt said, “You cannot drive a railroad spike with a tack hammer.”

He was no doubt referring to his prowess in bed.

JC: No doubt? [Laughs]

Well, he did have that reputation because he was the only true swinging bachelor we ever had. And he had this huge house, the only guy in the studio who owned a K-Par, which was the first automatic phonograph, which played something like ten 78s, and he had a big collection of erotica.

JC: Was the reason for wanting to play ten 78s because he didn’t want to get up and change the—

Well, that was in the days when there were no automatic players.

JC: Yes, but what was he doing that he didn’t want to get up and change the record?

Why does anybody? That’s why you buy LPs. You don’t like to get up every three minutes and change your record. Nobody to this day likes to.

JC: I thought maybe it had some connection with the—

Well, of course then he had thirty minutes—

JC: [Laughs] We could always tell that story.

But he had a Filipino houseboy. I think he treated him like a seeing-eye dog. Anyway, if the phonograph didn’t [garbled], the Filipino houseboy would change from a white jacket to a black jacket and sneak in and shut the machine off. By then, either one of them didn’t necessarily want to listen to music anyway. Bill Tytla, who roomed there with Babbitt for a year or so when he first came to work at the studio, said, “I told Art when I come home from a show or something, I gotta come in the side door, because I come every time the house is dark, and I don’t know who you got in there, and I was always afraid of stepping on Babbitt in a moment of ecstasy on the floor.”

But about those walks…I had nothing like that in mind. When I did them it had nothing to do with the people we were caricaturing, that was just to establish a different graphic personality. The walks had nothing to do with the person; it wasn’t a caricature of how a person walked. I decided this little guy will take little short steps, and Babbitt will take every other step, kind of like the Goof would walk. He was like the Goof.

JC: But Babbitt does walk with his rear end—

But that was no intentional copy.

JC: You are sure it wasn’t a caricature of his walk?

No, because in those days, jeez, if you could get a character just to walk, Christ, you were so effective.

JC: And the way that Tytla rode the horse. Tytla was a rider.

I know, but that had nothing to do with it. You hit a trotting, you hit every other beat, that’s just all I did. When you hit every other beat with a cartoon character, whether it be Tytla or anything, you try to get a funny thing. It had nothing to do with the people.

JC: He was, Tytla was, enormously flattered by that because it appeared in LIFE magazine, you remember?

Yes, I still think that’s crappy animation. If I knew what I knew three years later about animation, I could have done a much better job. I was a kid. I didn’t know my ass when I was doing that. I look at it now, and occasionally when I see it I go, “Oh, God.”

Over twenty more interviews and stories with Disney notables await you in "Walt's People: Volume 15".

In this excerpt, James Luske (son of Disney Legend Ham Luske) recalls to interviewer Jim Korkis what it was like growing up the son of a Disney animator, and hanging around with Walt Disney.

I was born on May 8, 1940. When I was one year old, Dad [Ham Luske] used me as the live-action actor for Baby Weems in the film The Reluctant Dragon. I had a good education and went to UCLA to study. What to study? I had no idea! My mother had been a teacher and suggested that I get a teaching credential so that I would always be able to get a job. I did that, and during the course work I needed, I took photography. That was it. I loved it. After long conversations with my father, and him asking a lot of questions at the studio, it was determined that it would be best to get into motion-picture photography. That is not easy, so I started delivering mail at the Disney Studio. About five years later, I was able to start at the bottom of the camera crew on a live-action picture. From there on, motion-picture work became my principal interest, except for a few girls. I was able to move to Hawaii and work there for about twenty-seven years, and I am now living in Canada, not working in the business.

Jim Korkis: How would you describe your dad?

JAMES LUSKE: My father was a very busy man working at Disney. He was the boss of the family without ever acting like one. One just didn’t want to disappoint him. He taught me many lessons. For example, I sold a motor bike to a friend of mine. He used it for a couple of weeks and it stopped working. He wanted me to take it back and get his money back. I talked to my father. He said the rule is “let the buyer beware” (quite a while ago), and my friend would have to keep the broken bike. However, my friend was quite poor, and that money was saved from about a year’s work delivering newspapers. Our family had more money and the motor-bike money wasn’t as much of a loss to us. So I took the bike back and returned the money. My father said he was proud that I had made that decision. Then he gave me the amount of money I lost.

My parents were the best anyone could have. Both were well educated and were hard working. They loved their children and did what they thought was best. Not always what we thought was best. We had a happy family and enjoyed being together on all occasions. We were not spoiled children, my mother saw to that.

Everything my dad did was funny. Once I found a pair of my mother’s shoes in his car. I asked him what they were doing there. He said that he had found some footprints in the mud in our backyard and he wanted to make sure they belonged to someone in our family. He said don’t tell anyone, because he didn’t want to scare anyone. Of course, I told my mother, who demanded to know what was going on. As it turned out, my father was buying my mother a pair of shoes for her birthday and wanted to be sure the size was right. He couldn’t just tell me that. He had to make a story of it.

I knew I could never draw like my father. He worked at home and some of his artwork was unbelievable. I had art classes in school and saw the difference. I do remember going to the studio. I was in high school or college, and my father was showing me a storyboard. He was trying to figure a story correction. I gave him an idea and he liked it. Don’t know or remember if it was used, but it did give me an idea that I might have a place in the studio.

One more thought. Since this is about my father, I want to get this point right. My sister indicated that my father was bad at business, didn’t do the family finances, and as a result did artwork. However, I think my father was very good at business, but if someone, my mother, would do the financial chores, so much the better. He did the real finances that ran the household, like purchasing and selling stock, etc. Some of the tips he gave me still hold true today.

The other item that bothers me is saying he was too quiet or meek in his work position. Comparing him to Ward Kimball, because they both had the same type of job, is like comparing Julie Andrews to Lady Gaga, because they both had the same job. Ward Kimball was an extreme extrovert. He wore different-colored socks, striped pants with checkered coats, and had long hair (a big “no no” at Disney). The idea that Walt kept Dad around because he always agreed with Walt is ridiculous. Walt didn’t need or want a “yes” man. He wanted someone who understood what a certain movie was about and someone who could help him achieve the end results.

An example was on a storyboard meeting for the animated feature Pinocchio. My father suggested that Pinocchio needed a conscience. Walt thought about this and agreed. I think Walt suggested Jiminy Cricket and that was added to the picture. My father was a cartoonist and published in the New Yorker magazine. His cartoons showed an understanding of humor that few people possess. This ability is why Walt needed my father’s input. Also, my father was a stubborn man, like I am. Many arguments or discussions with him proved that to me. He would never say “yes” to anything he thought was wrong, no matter who said it.

JK: What was your dad like at work?

I worked at Disney for years while my father was directing there. His position there was like it was at home. As far as I know, he wasn’t known to yell or scream at other employees, but there was no doubt that he was respected and whatever he said was done. People were always coming up to me and telling me what a great person my father was. I think other people in his position were very difficult to get along with. My father just got up and went to the studio. Later, when I went there with him sometimes, I found out his routine. He would drive to Bob’s Big Boy hamburger joint, sit down and have a breakfast, then drive to the studio. He worked there all day and then went home.

My father was very loyal to the men in his unit. There was a period when eliminating animation was being discussed by the executives at the studio. My father worried about this more than anyone realized. Not because he would lose his job, because he wouldn’t, but because some of his crew would. I think my father was just as excited about each project. I know from working on the television series Magnum P.I. that no matter what show we were working on, and no matter how good we thought a certain show would be, each show merited our best work and excitement. I think it was the same for my father. It was his work that mattered, not the show. He was proud of the Oscar [for Mary Poppins] and it was on the fireplace mantle.

JK: What was it like at the Disney Studio?

I learned to play golf on the studio baseball field, tennis on the sound stage wall, and drive in the parking lot. If I remember correctly, my father and I were there because my father went there weekends to work or catch up. I think he started the day showing me how to serve or hit a ball and then left me to practice as he went to work. I think my mother actually was in the car when I was driving in the parking lot. The studio was always a good memory for me. There was always something exciting, to a child, going on.

JK: Do you remember any stories your dad told about pranks that were played at the Disney Studio?

Just a few. One animator purchased a Volkswagen car and was going to see how many miles per gallon the car could go. So he filled the tank and recorded the mileage. He put a chart up on the wall. He was going to do this every week and see the results. After the first week, one of the animators secretly added a jar full of gas to the tank. So the chart showed improvement. The next week they added two jars and so on for the weeks to follow. After a while, the animator was getting record-setting mileage. Finally, he figured it out.

Another animator purchased a goldfish. Same story: they purchased a larger one each week and put it into the bowl. He was showing everyone how fast his fish was growing. Then they reversed the process and the fish kept getting smaller. He also finally figured it out.

There was a contest to see how many jelly beans were in a glass jar. One animator purchased a jar the same size and filled it with beans. Then he counted the number of beans. He was so proud that he showed everyone what he was doing and posted the number so that immediately when the winning number was displayed the unit could see how close he was. My father entered a number one bean larger than his number and another animator entered a number one smaller.

JK: What were your impressions of Walt Disney?

One story says it all. Walt hired an executive to help run the studio. I think he had owned some successful car agencies. The man was given an office in the Animation building, the headquarters of the studio. He immediately put his name on the door, Mr. such-and-such. He was in his office making a phone call and the gardener was outside mowing the lawn. I guess this man couldn’t hear the phone conversation because of the noise. He opened the window and yelled, “You son of a bitch, turn off that mower!” It wasn’t a minute later that Walt burst into the office. “I am the only son of a bitch at this studio. That gardener has been here twenty-five years. You yell at him again and you won’t be here twenty-five more minutes! And I am Walt. If I am Walt, you are not Mr. anything!”

Read more about Ham Luske, including interview with his other children, in "Walt's People: Volume 15".

About Theme Park Press

Theme Park Press is the world's leading independent publisher of books about the Disney company, its history, its films and animation, and its theme parks. We make the happiest books on earth!

Our catalog includes guidebooks, memoirs, fiction, popular history, scholarly works, family favorites, and many other titles written by Disney Legends, Disney animators and artists, Mouseketeers, Cast Members, historians, academics, executives, prominent bloggers, and talented first-time authors.

We love chatting about what we do: drop us a line, any time.

Theme Park Press Books

The Unauthorized Story of Walt Disney's Haunted Mansion The Ride Delegate 501 Ways to Make the Most of Your Walt Disney World Vacation The Cotton Candy Road Trip The Wonderful World of Customer Service at Disney Disney Destinies Disney Melodies The Happiest Workplace on Earth Storm over the Bay A Historical Tour of Walt Disney World: Volume 1 Mouse in Transition Mouseketeers Down Under Murder in the Magic Kingdom Walt Disney and the Promise of Progress City Service with Character Son of Faster Cheaper A Tale of Two Resorts I Saw Ariel Do a Keg Stand The Adventures of Young Walt Disney Death in the Tragic Kingdom Two Girls and a Mouse Tale Ears & Bubbles The Easy Guide 2015 Who's the Leader of the Club? Disney's Hollywood Studios Funny Animals Life in the Mouse House The Book of Mouse Disney's Grand Tour The Accidental Mouseketeer The Vault of Walt: Volume 1 The Vault of Walt: Volume 2 The Vault of Walt: Volume 3 Who's Afraid of the Song of the South? Amber Earns Her Ears Ema Earns Her Ears Sara Earns Her Ears Katie Earns Her Ears Brittany Earns Her Ears Walt's People: Volume 1 Walt's People: Volume 2 Walt's People: Volume 13 Walt's People: Volume 14 Walt's People: Volume 15

Write for Theme Park Press

We're always in the market for new authors with great ideas. Or great authors with new ideas. Whichever type of author you are, we'd be happy to discuss your book. Before you contact us, however, please make sure you can answer "yes" to these threshold questions:

Is It Right for Us?

We specialize in books that have some connection to Disney or theme parks. Disney, of course, has become a broad topic, and encompasses not just theme parks and films but comic books, animation, and a big chunk of pop culture. Your book should fit into one (or more) of those broad categories.

Is It Going to Make Money?

There's never a guarantee that any book will make money, but certain types of books are less likely to do so than others. They include: hardcovers, books with color photos, and books that go on forever ("forever" as in 400+ pages). We won't automatically turn down these types of books, but you'll have to be a really good salesman to convince us.

Are You Great to Work With?

Writing books and publishing books should be fun. The last thing you want, and the last thing we want, is a contentious relationship. We work with authors who share our philosophy of no drama and zero attitude, and the desire for a respectful, realistic, mutually beneficial partnership.

If you said "yes" three times, please step inside.