- Visit the Imagineering Graveyard

- Now Sailing: "Skipper Stories" - Tales from the Jungle Cruise

- Coming Soon: The biography of Disney animator Jack Hannah

- Coming Soon: A Haunted Mansion anthology

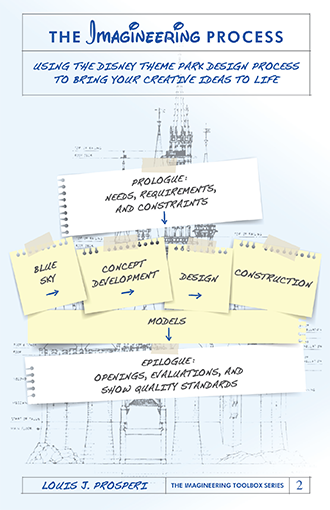

The Imagineering Process

Using the Disney Theme Park Design Process to Bring Your Creative Ideas to Life

by Louis J. Prosperi | Release Date: May 4, 2018 | Availability: Print, Kindle

A Master Class in Imagineering

When we think of Imagineering, we think of Disney theme parks. But Imagineering is a creative process that can be used for nearly any project, once you know how it works. Lou Prosperi distills years of research into a practical how-to guide for budding "Imagineers" everywhere.

The Imagineering Process is a revolutionary creative methodology that anyone can use in their daily lives, whether at home or on the job. Prosperi will teach you first how the Disney uses the Imagineering Process to build theme parks and theme park attractions, and then he'll show you how to apply it to your own projects, "beyond the berm."

You'll learn how to begin as the Imagineers begin, with an evaluation of needs, requirements, and constraints, and then you'll delve into the six stages of the Imagineering Process: blue sky, concept development, design, construction, models, and the "epilogue," where you hold your "grand opening" and assess the effectiveness of what you've built.

From there you'll see the process in action through a selection of interesting case studies drawn from game design, instructional design, and managerial leadership.

At the end of your master class, you may not be a bona-fide Imagineer, but you'll be thinking like one.

Table of Contents

Foreword

Introduction

Pre Show: A Bump Along My Journey into Imagineering

Part One: Peeking Over the Berm

Chapter 1: What Is Imagineering?

Chapter 2: An Overview of the Imagineering Process

Chapter 3: The Creative Process and the Power of Vision

Part Two: The Imagineering Process

Chapter 4: Prologue: Needs, Requirements, and Constraints

Chapter 5: Blue Sky

Chapter 6: Concept Development

Chapter 7: Design

Chapter 8: Construction

Chapter 9: Models

Chapter 10: Epilogue: Openings, Evaluations, and Show Quality Standards

Part Three: The Imagineering Process Beyond the Berm

Chapter 11: Another View of the Imagineering Process

Chapter 12: A Trip to the Moon and Birthday Parties

Chapter 13: Imagineering Game Design

Chapter 14: Imagineering Instructional Design

Chapter 15: Imagineering Leadership and Management

Post Show: Final Thoughts

Appendix A: My Imagineering Library

Appendix B: The Imagineering Pyramid

Appendix C: The Imagineering Process Checklist

Bibliography

Foreword

When I first read The Imagineering Pyramid by Lou Prosperi, I was struck anew by the realization that many of us are now leading themed lives in one form or another. This notion first occurred to me in 1991, shortly after I moved from Cleveland to Florida to pursue a career in the entertainment industry. Time magazine did a cover story on Orlando, which inexplicably featured a picture of the “California Crazy” architecture of Dinosaur Gertie’s ice cream stand at Disney-MGM Studios—I could think of plenty of other images that would have better supported their thesis, but at least the art of themed design was getting some national attention. The point of the story was that many of the longstanding principles of themed entertainment were starting to make their way out of the theme parks themselves and into the so-called “real world.”

Orlando was understandably ground zero for this movement that was not yet a movement. In addition to the 20-year old Walt Disney World and nearby Sea World, Universal Studios Florida had just opened its gates the year before, sending Orlando well on its way to becoming the unofficial theme park capital of the world. The article pointed out how theme park design flourishes could now be found outside the berm, so to speak, in the form of lushly landscaped roadways, carefully manicured gardens, picture-perfect manmade lakes capped with elaborate water features—even streetlights that suddenly possessed a lot more “character.”

Beyond these little design touches that elevated and enriched every civic environment in which they appeared, themed nighttime entertainment districts like Church Street Station and a new contender called Pleasure Island were transporting guests to another time and place for a few hours, providing a form of themed entertainment that had been previously confined to gated attractions. Planet Hollywood’s debut later that year, combined with the existing Hard Rock Café, launched the themed restaurant craze that would continue for the rest of the 1990s, resulting in popular chains such as Rainforest Café, Jimmy Buffet’s Margaritaville, and Bubba Gump’s. Heretofore “ordinary” places were becoming extraordinary, bringing small doses of theme park idealism and escapism into our everyday lives.

Perhaps the pinnacle of this movement, at least in central Florida, was the creation of the town of Celebration just outside the gates of Walt Disney World. Celebration replaced Walt Disney’s bold vision of EPCOT with a conscious return to the simplicity and innocence of the past, opting for small-town America over a city of the future. In a way Celebration was still very much infused with the spirit of Walt Disney; it’s just that its residents would now be living on Main Street, U.S.A. instead of Tomorrowland.

Everything from the center of town to the residences themselves were seemingly envisioned by a motion picture production designer, which actually made Celebration feel a lot more like a studio backlot than a real town in which real people lived and worked. Yet people flocked there from all over the world, most of them desperately seeking the idyllic existence they knew and loved from the theme parks. They wanted more of that Main Street idyll—all day, every day, if possible. They truly wanted to live the dream.

In the decades to come the principles of themed design would manifest in many different areas of our daily lives: planned communities, shopping centers, urban renewal projects—you name it and it was getting an experiential redesign or an aesthetic facelift to elevate the “guest experience” from the mundane to the sublime. And the magical makeovers were no longer confined to central Florida. David Caruso’s Grove and Americana complexes in Los Angeles are what you would get had Walt Disney himself ever set his sights on traditional shopping, combining dining, retail, and residential into compelling mixed-use destinations that transported its various constituents to other, better places. On the opposite coast, Disney itself helped spur a successful and equally controversial transformation of Times Square from a decaying urban wasteland into a family-friendly fantasyland in the heart of the city. Granted, I’ve spoken to more than a few New Yorkers who prefer the old wasteland, but everyone’s idea of ideal is different.

In the early 2000s I contributed essays and exercises to The Imagineering Way and The Imagineering Workout, two books that not only encouraged people to infuse their daily lives with magic, but also gave them pointers on how to do so. Those books were one of my first indications that the principles of themed design were starting to transition from commercial enterprises to personal applications, both in the home and at the workplace. This multi-decade evolution has now taken us from the theme park to the real world to our personal and professional lives.

This creative migration has been one I’ve followed with great interest, and so I was delighted to see Lou key into this movement and demonstrate how the principles of themed design can be applied to our everyday endeavors and help make the mundane magical, the ordinary extraordinary, and help enrich the stories of our lives. And now he’s taken an even deeper dive with The Imagineering Process, and I’m honored that he asked me to pen a foreword to a book that explores a creative evolution that has done so much to enrich the lives of so many.

The Walt Disney Company, NBCUniversal, and countless other owners and design firms will continue to do what they do so well in the theme park and resort space, creating unparalleled immersion and escapism for their guests. And a small army of restaurateurs, retailers, and real estate developers will continue to apply similar principles to their various real-world endeavors, creating little pockets of magic to help enhance our everyday lives. But now this movement has reached the individual—it has reached you—and I hope you will join it because a little creativity can help make your life better, brighter, and more fun. Why settle for the ordinary when the extraordinary is only a little dreaming and doing away?

So I hope you will read this book and come away from it energized, inspired, and motivated, because after all, if you can dream it—well, you know the rest.

Introduction

Over the last several years, creativity has become a buzz word in business. A Google search for “creativity in business” returns hundreds of thousands of hits. In his Creativity Works column on January 6, 2017, William Childs tells us that his “search on ‘books on creativity’ revealed that there are over 1.8 million of them.” If you read business books, blogs, or websites, you can’t help reading about the value being placed on creativity in the modern workplace. In a blog post called “Creativity Creep” from September 2, 2014, on The New Yorker website, Joshua Rothman describes this phenomena when he writes:

Every culture elects some central virtues, and creativity is one of ours. In fact, right now, we’re living through a creativity boom. Few qualities are more sought after, few skills more envied. Everyone wants to be more creative—how else, we think, can we become fully realized people?

Simply put, creativity has never been more in demand. In his Creativity Works column on January 3, 2017, Childs notes:

We now find ourselves experiencing what is known as the creative age. It’s the age of new ideas, new processes and innovative thought as a way to drive change and solve the complex challenges we face.

In the same article, entitled “The New Age of Innovation,” Childs writes:

While creativity is now being taken seriously as an economic driver, more work needs to be done before creativity is given the full status it deserves. The old stereotype of creative people sitting around on their beanbag chairs looking for meaning through the incandescent glow of their Lava Lamps still lingers.

Quoting Richard Florida, author of The Rise of the Creative Class, Childs adds:

If you are a scientist or engineer, an architect or designer, a writer, artist, or musician, or if your creativity is a key factor in your work in business, education, health care, law, or some other profession, you are a member of the new creative class.

I agree. I believe everyone is creative, even the people who tell you that they “don’t have a creative bone in their body”. In their book Creative Confidence: Unleashing the Creative Potential Within Us All, authors Tom Kelley and David Kelly refer to the idea that creativity is something that applies only to some people as “’the creativity myth.’ It is a myth that far too many people share.” They also tell us:

Creativity is much broader and more universal than what people typically consider the “artistic” fields. We think of creativity as using your imagination to create something new in the world. Creativity comes into play wherever you have the opportunity to generate new ideas, solutions, or approaches.

In The Creative Habit: Learn It and Use It for Life, renowned choreographer Twyla Tharp writes:

Creativity is not just for artists. It’s for business people looking for a new way to close a sale; it’s for engineers trying to solve a problem; it’s for parents who want their children to see the world in more than one way.

So now you might be saying, “Okay, I agree. Everyone is (or least can be) creative. That still doesn’t help me actually be creative. How do I do it?” Good question.

I think for many of us the challenge lies in finding the right model of how creativity and the creative process work so we can apply it in our own fields. This book is my attempt at providing just such a model. But before we get to that, I want to briefly look at something that lies at the heart of creativity and that plays a major role in the creative process: ideas.

I believe ideas hold a unique place in regard to creativity. Ideas are at the same time the most important and the least important part of any creative project. I know, that seems like a paradox, but bear with me.

Ideas are the most important part because every creative project starts with an idea. Good ideas are the basis for all successful creative projects. Consider the following:

- Without the idea to create “a place where adults and children can have fun together,” there would be no Disneyland (or other Disney parks for that matter).

- Without the idea to develop a technology to allow the creation of human-like robots in theme park attractions (Audio-Animatronics), we wouldn’t have attractions such as Great Moments with Mr. Lincoln, the Carousel of Progress, Pirates of the Caribbean, the Haunted Mansion, or countless others.

Of course, good creative ideas aren’t limited to those related to Disney parks:

- Without the idea to design and build a separate ship specifically for the moon landing, the Apollo program might not ever have succeeded in landing a man on the moon.

- Without the idea to create a Star Wars-based game for my son’s birthday party, my wife and I would have had to entertain 10 young boys all on our own.

Many people (myself included) believe in the importance of ideas, and there is no end to the books, blogs, and websites that offer tips and techniques to help us “be more creative” or “generate new ideas.” But generating ideas is not all there is to creativity. It’s important, to be sure, but it’s only one aspect of the challenge of employing our creativity. Ideas are only a part of being creative, and in some ways (here comes the paradox) they are the least important part. What’s equally (or perhaps more) important is how we follow through and develop our creative ideas, or as expressed by Guy Kawasaki in his November 4, 2004, Forbes article, “Ideas are easy. Implementation is hard.”

If you talk to people in traditionally “creative” fields (writers, artists, designers, etc.), ideas are never an issue for them. Most have more ideas than they could possibly implement in their lifetimes. Generating ideas is the easy part; it’s the execution of those ideas that’s difficult. The real work is in taking ideas and bringing them to life. Even the best ideas in the world can’t execute themselves, and without someone to execute them, even the best ideas in the world have little chance of becoming a reality.

I said earlier that I believe the challenge for many of us lies in finding a model for the creative process—an example that we can look to for concepts and principles that can be applied across a variety of creative fields.

Where can we find a model or example of the creative process? I think one of the best places to look is Disneyland and other Disney theme parks. More specifically, I believe one of the best models for creativity is found in the design and development of Disney theme parks, a practice better known as Imagineering.

As we’ll look at in more detail in the first part of this book, Imagineering was born from the blending of expertise from a number of fields, and just as the first Imagineers adopted techniques and practices from animation and movie-making to develop the craft of Imagineering, we can borrow (and steal) principles, practices, and processes from Imagineering and apply them in other creative endeavors.

I know of few better examples of creativity than Disney theme parks and Imagineering, and I’m not alone in this belief. Garner Holt and Bill Butler of Garner Holt Productions (the world’s largest maker of audio-animatronics) write: “Disneyland is still the ultimate expression of the creative arts: it is film, it is theater, it is fine art, it is architecture, it is history, it is music. Disneyland offers to us professionally (and to everyone who seeks it) a primer in bold imagination in nearly every genre imaginable.”

I’ve been a fan and “student of Imagineering” since my first visit to Walt Disney World more than 20 years ago. Even back when I was first learning about Imagineering, I recognized the value it could serve as an inspiration for the creative process, as I wrote in the following review of the first book in my Imagineering Library, Walt Disney Imagineering: A Behind the Dreams Look at Making the Magic Real:

This lavish coffee table book opens the doors on one of the most secret of divisions of the Walt Disney Company, namely Walt Disney Imagineering. These are the people that design, build, and create the various attractions at Disney theme parks and other locations (such as the Disney Store and DisneyQuest). This book explores the process by which the Imagineers conceive, design, and create Disney magic. Anyone interested in the creative process and imagination can benefit from reading this book, if for no other reason than as a source of inspiration for what is possible.

I’ve been amassing a collection of resources about Imagineering since that first visit to Disney World, trying to learn all I could about how the Imagineers work. In my search to learn as much as I could about this subject, I’ve identified a set of principles and a process that I believe can serve as a model for the creative process in a variety of fields. I call this set of concepts the Imagineering Toolbox.

The Imagineering Toolbox contains two main types of tools. The first is a set of principles focused on developing and communicating our ideas that I’ve organized into what I call the Imagineering Pyramid. This was the subject of my first book, The Imagineering Pyramid: Using Disney Theme Park Design Principles to Develop and Promote Your Creative Ideas. More specifically, that book looked at fifteen principles the Imagineers use as part of their design process and how those principles can be applied to other creative fields. What the Imagineering Pyramid doesn’t address is the process Imagineers use to develop their ideas into real-world parks and attractions. That’s the focus of this book, and is the second type of tool in the Imagineering Toolbox. The Imagineering Process is a simple process that can serve as a model for developing nearly any type of creative project, from a simple homework assignment to a fully immersive theme park attraction such as Expedition Everest at Disney’s Animal Kingdom.

The rest of this book is divided into three primary parts:

Part One: Peeking Over the Berm looks at the origins of Imagineering and the meaning of the word itself, as well as an overview of the Imagineering Process and the evolution of the process. This will give us a foundation on which we can expand in later chapters. We’ll also look briefly at the idea of having a “vision” and how that fuels the creative process.

Part Two: The Imagineering Process, the heart of the book, examines the process used by Walt Disney Imagineering in the design and construction of Disney theme parks and attractions. This section contains chapters devoted to each stage in the Imagineering Process. For each stage, we’ll look at how it’s used by Disney Imagineers, the goals of each stage, and how each can be leveraged in other fields.

Part Three: Imagineering Beyond the Berm explores how to apply the Imagineering Process to a number of specific fields, including game design, instructional design, and leadership and management.

Following Part Three is a Post-Show chapter in which I share some final thoughts, and a few appendices. Appendix A contains a list of the books, DVDs, and other resources in my Imagineering Library (as of this printing, anyway—it doesn’t stay the same for long). Appendix B provides an overview of the Imagineering Pyramid, and Appendix C contains a checklist of questions based on the Imagineering Process that you can use when bringing your creative ideas to life.

Louis J. Prosperi

Lou Prosperi worked in the game industry for 10 years as a freelance game designer and writer, and product line developer at FASA Corporation, where he worked on the Earthdawn roleplaying game. After leaving FASA, Lou went to work as a technical writer and instructional designer and has been in that role for the last 20 years, providing user and technical documentation and training for enterprise software applications. He currently manages a small team of technical writers and curriculum developers for a small business unit of a large enterprise software company.

Lou has been interested (or obsessed depending on who you ask) in Disney parks since his first visit to Walt Disney World on his honeymoon in 1993. A self-described “student of Imagineering,” Lou has been collecting books about the Disney company, Disney parks, and Imagineering for the last 12+ years. He rarely passes up an opportunity to add new books to his Disney and Imagineering libraries, and is nearly always thinking about his next trip to Walt Disney World. Lou lives in Wakefield, Massachusetts, with his wife and children.

About Theme Park Press

Theme Park Press is the world's leading independent publisher of books about the Disney company, its history, its films and animation, and its theme parks. We make the happiest books on earth!

Our catalog includes guidebooks, memoirs, fiction, popular history, scholarly works, family favorites, and many other titles written by Disney Legends, Disney animators and artists, Mouseketeers, Cast Members, historians, academics, executives, prominent bloggers, and talented first-time authors.

We love chatting about what we do: drop us a line, any time.

Theme Park Press Books

The Unauthorized Story of Walt Disney's Haunted Mansion The Ride Delegate 501 Ways to Make the Most of Your Walt Disney World Vacation The Cotton Candy Road Trip The Wonderful World of Customer Service at Disney Disney Destinies Disney Melodies The Happiest Workplace on Earth Storm over the Bay A Historical Tour of Walt Disney World: Volume 1 Mouse in Transition Mouseketeers Down Under Murder in the Magic Kingdom Walt Disney and the Promise of Progress City Service with Character Son of Faster Cheaper A Tale of Two Resorts I Saw Ariel Do a Keg Stand The Adventures of Young Walt Disney Death in the Tragic Kingdom Two Girls and a Mouse Tale Ears & Bubbles The Easy Guide 2015 Who's the Leader of the Club? Disney's Hollywood Studios Funny Animals Life in the Mouse House The Book of Mouse Disney's Grand Tour The Accidental Mouseketeer The Vault of Walt: Volume 1 The Vault of Walt: Volume 2 The Vault of Walt: Volume 3 Who's Afraid of the Song of the South? Amber Earns Her Ears Ema Earns Her Ears Sara Earns Her Ears Katie Earns Her Ears Brittany Earns Her Ears Walt's People: Volume 1 Walt's People: Volume 2 Walt's People: Volume 13 Walt's People: Volume 14 Walt's People: Volume 15

Write for Theme Park Press

We're always in the market for new authors with great ideas. Or great authors with new ideas. Whichever type of author you are, we'd be happy to discuss your book. Before you contact us, however, please make sure you can answer "yes" to these threshold questions:

Is It Right for Us?

We specialize in books that have some connection to Disney or theme parks. Disney, of course, has become a broad topic, and encompasses not just theme parks and films but comic books, animation, and a big chunk of pop culture. Your book should fit into one (or more) of those broad categories.

Is It Going to Make Money?

There's never a guarantee that any book will make money, but certain types of books are less likely to do so than others. They include: hardcovers, books with color photos, and books that go on forever ("forever" as in 400+ pages). We won't automatically turn down these types of books, but you'll have to be a really good salesman to convince us.

Are You Great to Work With?

Writing books and publishing books should be fun. The last thing you want, and the last thing we want, is a contentious relationship. We work with authors who share our philosophy of no drama and zero attitude, and the desire for a respectful, realistic, mutually beneficial partnership.

If you said "yes" three times, please step inside.