- Visit the Imagineering Graveyard

- Now Sailing: "Skipper Stories" - Tales from the Jungle Cruise

- Coming Soon: The biography of Disney animator Jack Hannah

- Coming Soon: A Haunted Mansion anthology

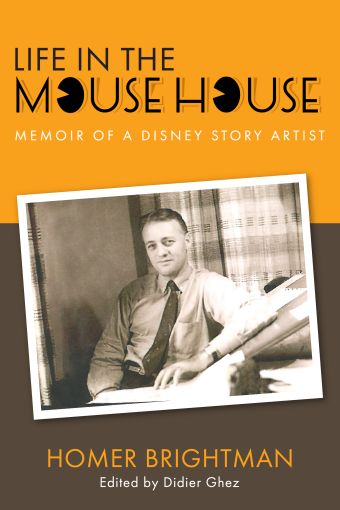

Life in the Mouse House

Memoir of a Disney Story Artist

by Homer Brightman | Release Date: March 3, 2014 | Availability: Print, Kindle

A Searing, Scathing Disney Memoir

From 1935-1950, story artist Homer Brightman worked on the biggest Disney projects: Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, Cinderella, the Oscar-winning short film Lend a Paw, and many others. A dream come true? Not really. Brightman's life in the Mouse House during Disney's Golden Age of Animation was tarnished by self-serving, power-hungry animators; by draconian policies and broken promises; and by Walt Disney himself.

Will the Real Walt Disney Please Stand Up?

Homer Brightman first encountered Walt Disney in the men's room of the Disney Studio in 1935. Another employee had just complained about Walt, not knowing that Walt himself was standing at the next urinal, and by lunchtime that employee found himself on the street, and out of a job.

Over the next fifteen years, Brightman experienced the highs and lows of working for a driven, complex, often ruthless businessman and creative genius, Walt Disney—the real Walt Disney, not the kindly, smiling "uncle" seen on television, nor the caring, patient mentor immortalized in company-sanctioned literature. Brightman presents the good and the bad, as he experienced them, and lets you ponder the contradictions of Walt's character.

Fun and Games and Politics in the Mouse House

When the Disney animators weren't creating classic films, they were pulling pranks—sometimes mean-spirited pranks—on one another. Brightman recounts how he and Harry Reeves once vandalized Roy Williams' (later the "Big Mooseketeer" on The Mickey Mouse Club) black limousine, and how Williams got back at Reeves that night by flattening the tires of his car. The prank includes improbable appearances by H.G. Wells and Charlie Chaplin, who dropped by Brightman's office on a tour of the studio with Walt, right after an angry Williams had smashed the glass panel of the office door.

When not pranking, the animators were politicking: Brightman goes into detail about the toxic political culture at the Disney Studio, where animators would jump to their feet and hide their work whenever another animator came around, steal credit for one another's ideas, and compete—often shamelessly—for the fickle favor of Walt Disney. The politics reach their crescendo in Brightman's nailbiting account of the Disney Studio Strike of 1941, and how Walt retaliated against those he felt had betrayed him.

In Life in the Mouse House, you'll read about:

- Brightman's penniless start at the Disney Studio on a cold day in 1935

- What really caused the Disney Strike, how Walt lost his cool, and the sad aftermath

- The foibles and eccentricities of well-known Disney artists, animators, and executives

- Walt's ill-fated "Field Day", his trip to Mexico, and his talent for physical storytelling

- What Brightman did after he left Disney, despite Walt telling him he'd never work again

And much more!

Homer Brightman wrote Life in the Mouse House in the 1980s. He died in 1988, and his book was lost until its rediscovery last year. When Brightman wrote the book, most of the people in it were still alive. He didn't want to offend them with his unflinchingly honest, provocative narrative, and so he changed the names of such luminaries as Ken Anderson, Perce Pearce, Ted Sears, Harry Tytle, and Roy Williams.

Nearly thirty years after Brightman's death, and the deaths of virtually everyone he worked with at Disney, we can now reveal the identities of characters like Muggle (Ken Anderson), Snojob (Perce Pearce), Crock (Card Walker), and over three dozen others. You'll read about these beloved Disney legends—including Walt Disney himself—as you've never read about them before.

Come share Homer Brightman's life in the Mouse House!

Table of Contents

Foreword by Melinda Heller Nalos

Preface by Pamela Etzler and Connie Heller-Zeiger

Editor's Introduction by Didier Ghez

Introduction by Homer Brightman

Chapter 1: Homer Gets Hired by Disney and Meets the Boys

Chapter 2: Homer Speaks Up at a Story Meeting, and Walt's Reaction

Chapter 3: Homer Draws a Fat Lady Cartoon, and Nearly Gets Evicted

Chapter 4: Walt Scowls, Says "Shit!", and Storms Out of a Story Meeting

Chapter 5: Vandalism, Violence, and Sexual Innuendo: A Day at the Studio

Chapter 6: Homer Learns that Some Disney Animators Can't Be Trusted

Chapter 7: Walt Reneges on His Promise to Share Profits from Snow White

Chapter 8: Walt Builds a Bureaucracy, One Petty Memo at a Time

Chapter 9: Winners and Losers from the Disney Studio Strike of 1941

Chapter 10: Homer Gets the Cold Shoulder from Disney Strikers

Chapter 11: Walt and Homer Go to Mexico

Chapter 12: "Mert Kibble" Reaches for the Stars and Falls on His Ass

Chapter 13: Homer Gets His Dream Assignment: Cinderella

Chapter 14: Walt Kills the Dream, and Homer Walks Out the Door

Homer Brightman: Life After Disney

Homer Brightman: Filmography and Comicography

Foreword

I grew up hearing stories. After all, my grandfather Homer was a storyteller, both by nature and by vocation. He told me stories, laughing, about the pranks he pulled on his two daughters: my mother, Connie, and her younger sister, my aunt Pam. There were simple things, such as replacing their regular breakfast milk with pure buttermilk, and more complex tricks, like when he put an inflation device under my mother’s dinner plate and each time she would start to take a bite, her plate would rise! He loved gags!

There were only two things my grandfather loved more than a good gag; one of those was the sea. Sailing was his first love and his lifelong love. He was born October 1, 1901, in Port Townsend, Washington, on the edge of the Pacific coast. His father, Homer H. Swaney, the president of Seattle Iron and Steel Company, died in those rough waters when my father was two years old, the result of a tragic ferry boat accident. As an adult, Grandpa Homer decorated his house with pictures of magnificent sailing ships on stormy seas, water crashing over the decks. We would stand together and talk about those paintings.

“Was it really like this, out there?” I would ask, finding it hard to believe, sure there was exaggeration on the canvas.

“That’s the way she was,” he would reply, telling stories of the sea from his Merchant Marine days.

He told me the story of how he ran away from home at fifteen to join the Merchant Marines. He loved sailing to the Orient and spoke highly of the skilled dentist in Shanghai who put the gold between his teeth. Over and over, I heard how his life was saved on one trip to China by a giant sea turtle. A huge wave took him overboard, when he was the third mate and the night watchman. He was just about to give up—three hours in the cold water—not able to tread water one minute longer, when out of the churning sea came this giant turtle. He was able to hold onto it until the boat came back for him.

My favorite story, however, was the very short story of his birth. Every one of us heard this story whenever we asked him where he was born. Port Townsend never once came out of his mouth.

“I was not born. I had no parents. I was found strapped to a log, floating in the sea.”

We were never quite sure if that was the truth, so we all kept asking! I was, however, sure about the sea turtle story, and I never tired of hearing it. Growing up, I often thought my own life would not have been, had this turtle not saved him!

He was so convincing when he spoke! He acted out every story, throwing his arms in the air like waves, flapping his hands like wings, as he told me the story of the waterlogged bee he saved, flying directly at him and putting him in the pool fully dressed.

There are many references in the volumes of Disney biographies to Homer Brightman being quite demonstrative in the telling of his stories during his days working at the Disney Studio as a storyboard artist. One recounts his telling of a Donald Duck cartoon and the entire room going to pieces in laughter. Walt turns to his stenographer and asks her if she is laughing at the story, to which she replies, “At Homer!”

If tuberculosis had not gotten hold of my grandfather in the 1920s, he might have stayed sailing the seas his entire life. A doctor landlocked him in a sanatorium in Chicago. A few months later he sent away for a basic drawing course. He recovered and began sending cartoons to the Saturday Evening Post. As you will read, he made his way to the Disney Studios in the 1930s, where he worked for free the first few weeks and then for $15 a week.

It is there, in southern California, where he brought stories to life for Walt Disney, and settled into his own life with the other thing he loved more than gags: his family. He and my grandmother, Rosalind Smith Brightman, raised my mom and my aunt on Lee Drive. Homer became a member of a small group of men who were known as the Disney storyboard artists. This is where he reinvented fairy tales and gave his characters a voice. He told me in his later years his favorite creation, favorite character of all, was the shy, plump mouse, Octavius, known as “Gus Gus”, from the movie Cinderella. He wrote all the mice into the story, giving them personalities and bringing them to life. When I watch his movies or cartoons I feel I am once again sitting beside him, listening to his stories and laughing. His personal characteristics of kindness, generosity, and his original sense of humor shine through in his work. It is in the movie Mickey and the Beanstalk, in particular, that I recognize him. My grandfather’s personality is there in Donald, Goofy, and Mickey as they sit at the kitchen table, slicing the bread and the very last bean!

In my family, one also heard stories of that famous man on the television, Walt Disney. My grandfather clearly loved his work, but not working for Walt. There is always more than one side to a story, and, as we learned, more than one side to Walt Disney. Yes, he was the smiling man on the television Sunday evenings. However, I heard stories of how he behaved toward his employees, never giving them credit, grumbling as he walked down the hallways smoking a cigarette, or scowling at them when he bumped into them in the restrooms at the Studio. Walt was the kind face and warm voice I enjoyed on TV, but Grandpa Homer described a very serious, driven, and unfriendly man, off-screen. Life in the “Mouse House”, as my grandfather called it, could often be unpleasant and stressful. Good thing my grandpa Homer always kept his sense of humor.

My grandfather lives on in time, through his stories and characters, through his children and grandchildren. The Disney Studio grew over time and became a large company with a life of its own; however, when you return to its foundation, go back to the Golden Age of Disney, you will find Homer Brightman and a group of hard-working, talented “gag-men” who came together and gave the world the gift of their stories.

Preface

High on a shelf, in a dusty old box, alone in a closet, sat a story waiting to be told for over thirty years. The story contained our father’s experiences over a fifteen-year period when he was employed at what he loved to call the Fantasy Factory—the Disney Studio. It was not until this spring, when Didier Ghez, a long-time Disney enthusiast and historian, tracked my sister and I down, in search of one more hidden memoir of the long-lost artists that were in the employ of Walt Disney during those wonderful Golden Years of the 1930s, that the book came out of the box.

In January 1904, en route to Victoria, British Columbia, for business, Homer’s father, Homer Swaney, was aboard the steamship Clallam, carrying over ninety passengers. During the night, the Clallam encountered hurricane-force winds, leaving her adrift until she finally sank in the Straits of Juan de Fuca, only miles from Victoria. Mildred, left with two small sons to raise (Homer had one younger brother John who was born in 1903), moved to Seattle, Washington. Years later, she married Frank Brightman, adding two daughters to the now lively family of four. Our father always had dreams as a young boy, now living on Mercer Island, of being a sea captain sailing the world. He would take his mother each week across Lake Washington on the family skiff to Steward Park to catch a horsedrawn buggy that would carry them to the Pike Street Market for their weekly shopping. He often told of how he would see himself in that skiff, sailing the seas with heroic stories of pirates, adventure, and far-away lands. At the age of seventeen, he attended a Maritime Academy in Seattle, where he received certification in high seas navigation and a second-mate license.

After completion of his studies, he was employed by the Robert Dollar Steamship Lines, based in Seattle, working as an apprentice on sailing ships. Then, in 1919, he boarded the A.V. Gregory, bound for Sydney, Australia. Often we would listen to the heroic and scary stories of the crew as they sailed around Cape Horn in wintry conditions. Later in his career he was raised to the position of second mate, sailing on large freighters across the Pacific to the Orient. Dad was soon offered a position in the Shanghai offices for two years, and then transferred to Hong Kong and later to Singapore, where he was under employ for eight years.

Upon returning to New York on business for the Dollar Steamship Lines, he met up with his folks for a much-needed visit. It was at that time his family saw that he was not well and scheduled him to see their family doctor. Our dad received the diagnosis of an advanced case of tuberculosis and was given six months to live. Needless to say, he had staying power. It was during those many years of recovery that he would formulate stories of his travels to the delight of many of the patients that were working toward recovery themselves.

After three years of convalescence in a sanatorium in Tucson, Arizona, he was discharged and traveled back to Chicago to be with his family. It was there that he met our mother, who had recently graduated from Beloit College in Wisconsin and was working as a fill-in secretary for our grandfather. He adored our mother, and they were married on July 24th, 1935, in Chicago. They had a long, wonderful forty years of marriage, leaving both my sister and I with incredible role models. Our dad would often say, years after mom’s death, that he would never marry again, since “When life gives you the best friend and wife ever, why would you want for more?”

Every Sunday was our day: girls’ day out with Dad! We loved it! Often, he would take us to Griffith Park to ride on the carousel, for what seemed hours at a time. We would then go to the zoo to make it a day, and sometimes stop by downtown Glendale on the way home for hot fudge sundaes, or, better yet, stop by this tiny little take-out stand, run by a local school teacher, for sliced barbecue beef and ribs. He claimed it was the best barbecue he had ever eaten in his life, and I have to agree—it was special.

Dad loved to swim, and had a swimming pool built in our backyard. When he came home from work, he would always make a grand entrance with a huge splash and play with our friends, tossing us in the air, and always turning time in the pool with giant races; races, of course, that he never won.

He always loved animals and our home, at times, seemed to have just too many pets. We had a cat named Tuffy; a dog, whom we adored, named Billie; and every Easter we each would get a pink and blue baby chick, much to our mother’s chagrin. We also had two miniature turtles that lived in a bowl with plastic palm trees that sometimes found their way out of their cramped surroundings, and it was always a task locating them. One day they just disappeared, never to return, and I always felt Mom had something to do with that.

Our father was always a born storyteller, even from a young age, and both my sister and I would sit with the fondest memories of our time spent with him as he would go over his storyboard drawings like he was handling a deck of cards. Often, he would stop and say, “Why didn’t you laugh?”, and when we would explain he would drop that gag and go back to the drawing board. He always wanted to make us laugh, and he was never short of jokes and fun antics.

Our parents loved to dance, and both my sister and I loved nothing more than going to the Oakmont Country Club for dinner and getting to dance with Dad. They had this very tiny, little organ that an older lady would play for hours. We loved watching Mom and Dad dance while waiting our special turn with Dad. Those were memorable times, when we could feel all grown-up, waltzing around the dance floor with Dad all to ourselves. Dad was devoted to his family, but our time with him did come with a hidden cost. My bedroom was close to the kitchen and often, when I would get up in the middle of the night, Dad would be sitting, hunched over his drawing board, at our kitchen table, coming up with a story and gags to make children laugh. He spent a great deal of time working at two and three in the morning, yet always seemed full of pep the next day, coffee in hand, talking with Mom while she prepared breakfast for us before heading out to school. It wasn’t until later in life, when both my sister and I became parents ourselves, that we did marvel at what a kid at heart our father was, and how and where he always found the time for us, be it combing the beach at Balboa for shells, teaching us to jump rope, ride bicycles, climb trees. It was his wonderful way of showing us his love.

Dad never tired of telling stories and making people laugh, and in his later years, while living in a retirement home, he would help others who were less fortunate than himself. Several such men who sat at his table for meals were stroke victims and had lost the use of their voices. It made ordering a meal laborious and hard for them, so at each meal Dad would bring to the table his old grease pencils and draw pictures of each menu item on the paper tablecloths, along with the condiments and salad dressings, so they could point to the item of choice. Of course, the items he drew sometimes did not make the food look delicious, depending on what Dad liked or disliked, so it was not uncommon to see our father in serious discussion with the head chef, much to the delight of his silent friends. They loved him, as he made their disability a little more tolerable, adding humor to their struggles.

Introduction

Most of the talented artists who knew and worked with Walt Disney are gone. Those who have never or seldom been interviewed took their precious memories to the grave.

Or did they?

Thankfully, for Disney history addicts like myself, there are still hidden autobiographies and memoirs to be unearthed: from the legendary 1938–1948 diaries of animator Ward Kimball; to the not-yet-released autobiography of concept artist Mel Shaw, Animators on Horseback; or the recently discovered notes of Eric Larson for his book 50 Years in the Mouse House. Needless to say, those documents are extremely rare and of uppermost value to Disney historians and Disney enthusiasts alike.

So when I found traces of a memoir written by a story artist of Disney’s Golden Age, in the archives of Disney historian Michael Barrier, I knew that I had hit “pay dirt”. The story artists worked closer to Walt than any of the other artists, and they were at the center of the Studio’s creative process. The ’30s were the most exciting creative period at the Studio. And Homer Brightman, despite having collaborated on dozens of shorts and quite a few features, was one of the lesser-known artists of that era. I knew that his book would be fascinating and enlightening.

After tracking down Homer’s daughters, Pamela Etzler and Connie Heller-Zeiger, and after reading the book, I was glad to confirm that its contents are indeed exhilarating from a Disney history standpoint.

There are dozens and dozens of stories in this volume which are either brand new or shed new light on what we already knew: hilarious memories of fellow story artists Harry Reeves, Perce Pearce, Roy Williams, Webb Smith, and many others; new information about the career of animator Frenchy de Trémaudan; new details about the events of the 1941 Studio strike; and, almost on every page, new elements that help us “connect the dots” when it comes to artists and events. In other words, I learned something exciting and fun in each chapter.

But there is also a darker side to Homer Brightman’s memoir. One can feel that his fifteen years at the Studio were not a happy time professionally and emotionally. The man we discover is one who, while at the Disney Studio, suffered due to internal politics, constant fear of losing his job, and artistic frustrations. This unhappiness leads to a very dark portrait of Walt. We all know that Walt was not a saint and could be a harsh taskmaster. Many of Homer’s colleagues, however, had a very different point of view on Walt as a boss and as a human being. Many of those positive perspectives are shared in the pages of the book series Walt’s People.

In other words, as is always the case when reading an autobiography, it is important to keep in mind that Homer Brightman’s perspective is subjective. His point of view is nonetheless a very important one, his story fascinating, and his prose so clear that his book, from day one, is a delight to read.

When he completed his book in 1986, Homer decided to hide the names of his co-workers behind pseudonyms. Homer’s daughters, Pam and Connie, felt that the body of the book had to be released exactly as Homer had left it, with the only addition of a few endnotes to clarify a few facts and the rare faulty memories. Thankfully, both also realized that the book takes another dimension when one knows who are the artists hidden behind the pseudonyms. I am therefore enclosing below a list of the names of the individuals we believe we identified, thanks to notes left by Brightman as well as some additional research completed while working on this manuscript. I strongly encourage you to make reference to this list while reading Homer’s memoir.

Life in the Mouse House is an enlightening adventure, which for Homer ironically started on a grey morning of February 1935…

The "Cast" of Life in the Mouse House

Homer Brightman gave aliases to the Disney artists and animators in his book because at the time he wrote it most of them were still alive, and his characterizations were often harsh. Brightman's daughters wanted to keep the aliases intact, per their father's wishes. As a compromise, I included a "legend" in the book that matches aliases with real names. Here's our cast:

|

|

Homer Brightman

Homer Brightman was one of the members of Disney’s Story Department from 1935 to 1950, right in the middle of the Golden Age of Disney animation.

During those fifteen years, he was often teamed with another legendary story artist, Harry Reeves, and was instrumental in developing dozens of storyboards for some of the most famous Disney shorts, many of them featuring Donald and Pluto. Among the classic shorts tackled by Brightman: Alpine Climbers, The Fox Hunt, Clock Cleaners, Beach Picnic, The Fire Chief, and Lend a Paw. Brightman also worked on several of the features, including Snow White, Pinocchio, Bambi, Saludos Amigos, The Three Caballeros, Make Mine Music, Fun and Fancy Free, Melody Time, The Adventures of Ichabod and Mr. Toad, and Cinderella.

As part of the Story Department, Brightman was at the very heart of the Disney Studio, and worked with some of its stars, including Ted Sears, Dave Hand, Perce Pearce, Roy Williams, Carl Barks, Ham Luske, and Frenchy de Trémaudan.

After Disney, Brightman joined UPA, MGM, and Walter Lantz. He passed away in 1988.

In this excerpt, from Chapter 2, Homer finds the nerve to speak up at one of Walt Disney's story meetings. Note: Homer Brightman gave aliases to the Disney artists and animators in his book, because at the time he wrote it most of them were still alive, and his characterizations were often harsh. I've identified the aliases in this excerpt. In the book, all the aliases are identified.

It was rumored that Walt’s execs pounded the “Three Musketeers” theme into the artists—“All for one and one for all”—a happy family working for Walt and a great future. I was told that long before I came to the studio, the storymen had discovered things weren’t just that way. They said Walt didn’t give a damn whose gag it was, as long as it improved the picture, and a spirit of secrecy had developed among the storymen. Generosity vanished, and, gag-wise, they became tighter than a gnat’s ass.

Strayshott [Webb Smith] asked me what I was doing, and I said I was working on gags for a Christmas picture about broken dolls and had come up to see Mr. Sligh [Ted Sears], but he wasn’t in. “Just leave ‘em on his desk,” Strayshott said. I thanked him and said I couldn’t resist the open door, and, glancing through the story, saw a gag for the dog Pluto. Strayshott was about to look at it when a shattering cough was heard. He chuckled, “That’ll be Walt or Clem Longshanks [Carl Barks]. They’ve both got God-awful coughs.”

Just then, a short, pot-bellied, middle-aged fellow walked in. His sparse brown hair was parted in the middle. He was apparently an old-timer in the business, and it didn’t take long to tell he had bronchitis, and bad. Several other fellows drifted in. I learned later one of them was Diddle [Joe Grant]. He smoked a pipe and asked, in a relaxed manner, “Is this where the execution takes place?” He dropped into a chair next to the yellow wicker chair. Then a thin, tall fellow strolled in. He had on a white shirt and a fore-in-hand tie that seemed too short for him. He had a red face, a shoe button nose, a long upper lip, and a receding chin. His black hair was combed straight back from a low forehead. His murky eyes coasted around the room taking me in, and I noticed they were empty, devoid of any feeling. He was greeted with “Hi, Si.” So that was Sligh, and I was seeing him for the first time.

I started to leave the room when a smiling young girl breezed in carrying a steno machine. I stepped aside for her, just as Walt charged through the door. He brushed past me and slumped into the wicker chair amidst a chorus of “Good morning, Walt.” He ignored the greetings: eyebrows arched, he was glancing around abruptly and shot a glance at me, as if to say who the hell are you? Then he turned back to the storyboards. Apparently, he took in everything.

Once again, I was struck by his resemblance to a Spaniard. He had a high-bridged nose, a small black mustache, and thick, straight, dark hair. But I knew by now that he was of Scottish-Irish descent. He wore dark slacks and a dark blue, short-sleeved jersey with narrow horizontal stripes of a lighter hue. Although he was slightly built and of medium height, he was large-boned with the physique of a guy who lifted weights. His forearms were muscular, and he had big boney hands with long sturdy fingers, and those fingers were never still during the meeting, plucking at loose pieces of wicker or drumming impatiently on the arm of his chair. He glanced around the group and said, “Alright, Clem, let’s get on with it.”

Longshanks wheezed out a bronchial blast and pointed to the first drawing with a wooden pointer. He began describing the actions of Mickey and Donald climbing the mountain. Suddenly, Walt interrupted, “We want a little fast music to begin with and a blend of yodeling from Mickey and the Duck.”

“Good, Walt,” said Longshanks. He had barely resumed when Walt cut in again. “Every time they drive their picks into the mountain they should do a leap frog effect, like a spring, and yodel right after it.”

“Right.” Longshanks had reached the third sketch. Walt frowned.

“What about Pluto?” he said. “He’s got to do something. He can’t hang around like a sack of potatoes.”

A thoughtful silence fell over the room. This was one of the most important moments of my life. An idea popped into my mind. I was still making only $15 a week. Some of the fellows had told me the only way to get ahead was to impress Walt, personally.

Here he was, and now was my chance to do it. Nobody here was going to do it for me. I listened to my voice break the silence, as if it was the voice of a stranger. “What if a little bush grows on the side of the cliff and Pluto tries to sniff it but gets yanked away.”

Walt came to life. He swung around to face me. “That’s good!” he said. I felt like I’d won the sweepstakes. A lot of grim smiles surrounded me, but I ignored them and resolved to come up with anything else that seemed funny.

“We can use this gag a couple of times,” Walt was saying.

“Every time Pluto tries to sniff a bush or a tree he gets yanked up. He’s helpless.”

Sligh said, “We can use it for a running gag.”

Walt was talking directly to me. “That’s good dog personality stuff. That’s the type of gag we need around here.”

Then he looked back at the boards, and I glanced at Sligh. He was snow-white under the eyes. I began to sweat.

Meanwhile, Longshanks went on with his story. “Mickey is up first and he pulls up the duck. Then both of them pull Pluto up and the duck ties Pluto to a boulder.” Then I interrupted him, “Could Pluto look back over the edge of the cliff and make a frightened ‘take’? He backs up and puts his paws over his eyes.”

Walt laughed for the first time. “He’s frightened. He cringes.”

Longshanks said the duck had gone off to pick edelweiss while Mickey hunted for eagle eggs. He had a lot of stuff drawn up for Walt to shoot at, but Walt ignored the storyboards. He turned to the group, and, without hesitating, went through a non-stop funny routine. I was impressed. He was a hell of a gag man. He jumped to his feet and went on like this: “Mickey starts picking up eagle eggs in excitement. He’s real happy, then a dark shadow comes into the scene; Mickey looks up and sees the mother eagle sitting on top of a boulder, watching him. Mickey gives an embarrassed chuckle and starts putting the eggs back in the nest, one at a time. All the time, he keeps an eye on the mother eagle. She watches him with a fierce expression. He puts the last egg into the nest, but drops it. A little eagle pops out. Mickey tries to pat it.

“‘Nice little guy,’ he says, but the eagle nips his finger. Mickey lets out a yell and the mother eagle zooms down at him. He fires eagle eggs at her, and as he throws them, they pop open and little eagles come sailing out. They attack Mickey. He covers his head and shoves them into Pluto’s scene. All the time, the old girl is on the rock. She’s urging her little eagles on. Pluto comes to Mickey’s aid, running around the boulder with the rock he’s tied to bouncing along behind him.”

Then Walt fell silent and slumped back into his chair.

He fished in his pocket and pulled out a crumpled pack of Lucky Strikes. Diddle, seated beside him, held a match while the rest of the men were saying, “That’s great, Walt…funny stuff.” Everything he said was fresh and funny and in continuity. That was the marvel of it. I knew then he wasn’t Walt Disney for nothing. He seemed to be talking to himself. “What do we do with the Duck?”

“The Duck’s collecting flowers and singing,” said Longshanks.

“He can’t just pick flowers. I want him to do something funny,” said Walt, impatiently.

I had it. “He’s got a bunch of edelweiss; just as he holds it up to admire it, a little mountain goat pops out from behind a rock and chomps the flowers off, leaving the surprised Duck holding the stems.”

“He gets madder than hell,” cried Walt.

Everybody began tossing out gag ideas, and we developed a lot of back-and-forth stuff between the little goat and the angry Duck.

Walt got hot again. “Another little goat joins the first little goat and they come at the Duck from different directions and try to butt him. He picks up a rock and holds it between them and they butt it. The Duck laughs and then finds he’s facing the old man goat.”

Walt stopped again.

“The old man goat butts the Duck up the side of a cliff; he’s kayoed,” suggested Longshanks. “We come back to him later.” He ended with a wheezy cough.

“I wish we had something better than that,” said Walt.

I was so excited about being in a story meeting with Walt that I was thinking myself crazy. I stood up without realizing it. “The old man goat butts the Duck up an ice hill. He slides down and gets butted up again.”

Longshanks interrupted me. “What’s so funny about that?”

“Wait a minute, I’m not finished,” I cried. “After getting butted up the hill a couple of times the Duck loses his temper and butts the old man goat.”

“Too corny,” said Sligh.

Walt swung around to face him, “Corny? What’s corny about it?” he cried. “The Duck’s got a helluva temper, hasn’t he? So he turns around and runs straight at the old man goat, who comes straight at him. We cut back and forth like two trains coming together, and, BLAM, the old goat flies out of the scene and lands flat on his back, dizzy as hell.”

Everybody cracked up, but Walt scowled. “Maybe we’re getting too straight around here. Maybe we need to go a little farther.”

I could feel everybody in the room tighten. I looked at my watch; a quarter to twelve. The group seemed restless and tired, but Walt was just getting steamed up. He was able to do the whole story by himself. He didn’t need any help; just a couple of cigar store Indians to bounce his stuff off of. He described everything clearly as if it had taken place on a picture screen in his mind. With everybody itching to go to lunch, Walt was hot.

About Theme Park Press

Theme Park Press is the world's leading independent publisher of books about the Disney company, its history, its films and animation, and its theme parks. We make the happiest books on earth!

Our catalog includes guidebooks, memoirs, fiction, popular history, scholarly works, family favorites, and many other titles written by Disney Legends, Disney animators and artists, Mouseketeers, Cast Members, historians, academics, executives, prominent bloggers, and talented first-time authors.

We love chatting about what we do: drop us a line, any time.

Theme Park Press Books

The Unauthorized Story of Walt Disney's Haunted Mansion The Ride Delegate 501 Ways to Make the Most of Your Walt Disney World Vacation The Cotton Candy Road Trip The Wonderful World of Customer Service at Disney Disney Destinies Disney Melodies The Happiest Workplace on Earth Storm over the Bay A Historical Tour of Walt Disney World: Volume 1 Mouse in Transition Mouseketeers Down Under Murder in the Magic Kingdom Walt Disney and the Promise of Progress City Service with Character Son of Faster Cheaper A Tale of Two Resorts I Saw Ariel Do a Keg Stand The Adventures of Young Walt Disney Death in the Tragic Kingdom Two Girls and a Mouse Tale Ears & Bubbles The Easy Guide 2015 Who's the Leader of the Club? Disney's Hollywood Studios Funny Animals Life in the Mouse House The Book of Mouse Disney's Grand Tour The Accidental Mouseketeer The Vault of Walt: Volume 1 The Vault of Walt: Volume 2 The Vault of Walt: Volume 3 Who's Afraid of the Song of the South? Amber Earns Her Ears Ema Earns Her Ears Sara Earns Her Ears Katie Earns Her Ears Brittany Earns Her Ears Walt's People: Volume 1 Walt's People: Volume 2 Walt's People: Volume 13 Walt's People: Volume 14 Walt's People: Volume 15

Write for Theme Park Press

We're always in the market for new authors with great ideas. Or great authors with new ideas. Whichever type of author you are, we'd be happy to discuss your book. Before you contact us, however, please make sure you can answer "yes" to these threshold questions:

Is It Right for Us?

We specialize in books that have some connection to Disney or theme parks. Disney, of course, has become a broad topic, and encompasses not just theme parks and films but comic books, animation, and a big chunk of pop culture. Your book should fit into one (or more) of those broad categories.

Is It Going to Make Money?

There's never a guarantee that any book will make money, but certain types of books are less likely to do so than others. They include: hardcovers, books with color photos, and books that go on forever ("forever" as in 400+ pages). We won't automatically turn down these types of books, but you'll have to be a really good salesman to convince us.

Are You Great to Work With?

Writing books and publishing books should be fun. The last thing you want, and the last thing we want, is a contentious relationship. We work with authors who share our philosophy of no drama and zero attitude, and the desire for a respectful, realistic, mutually beneficial partnership.

If you said "yes" three times, please step inside.