- Visit the Imagineering Graveyard

- Now Sailing: "Skipper Stories" - Tales from the Jungle Cruise

- Coming Soon: The biography of Disney animator Jack Hannah

- Coming Soon: A Haunted Mansion anthology

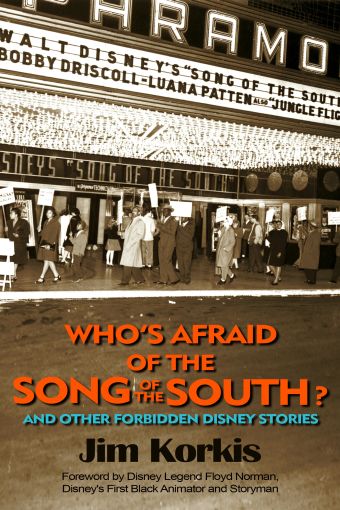

Who's Afraid of the Song of the South?

And Other Forbidden Disney Stories

by Jim Korkis | Release Date: November 30, 2012 | Availability: Print, Kindle

The Real Dark Side of Disney

You won't find it on cable. You won't find it on NetFlix. Ever. Disney thinks that you can't handle Song of the South, a film that Walt Disney himself championed from contentious start to controversial finish. Jim Korkis chronicles the sad ballad of this forbidden film, lynched by the politically correct and banished to the deepest, darkest depths of the Disney vault for its "racist" storyline.

Silencing the Song of the South

The last time Americans could legally watch Song of the South was in 1986, before Disney pulled it from cinemas. For those confident of an eventual re-release, Disney CEO Bob Iger advises: "Don't expect to see it again…ever."

But even if you can't watch Song of the South, you can still read about it—and what a fascinating story Korkis spins, covering everything from the original Uncle Remus stories, the behind-the-scenes politics and problems of filming what was even in the 1940s a sensitive issue, and such topics as Walt Disney's alleged racism, the hypocrisy of Splash Mountain, and a provocative Disney skit on Saturday Night Live.

Sex, Sleaze, and Suicide

Korkis covers much more tawdry territory than just Song of the South in this book. He'd also like to whisper in your ear seventeen forbidden Disney tales, including:

- Disney's cinematic attack on venereal disease

- Walt Disney's nightmares about stomping an owl to death

- Disney Legend Ward Kimball's obsession with UFOs

- Wally Wood's Disneyland Memorial Orgy poster

- Mickey Mouse's multiple attempts to commit suicide

Racism. Sex. Pornography. UFOs. Disney. What are you waiting for?

Table of Contents

Foreword by Floyd Norman

Introduction by Jim Korkis

Part One: Who's Afraid of the Song of the South?

Song of the South: The Beginning

Song of the South: The Screenplay

Song of the South: The Cast

Song of the South: The Live Action

Song of the South: The Animation

Song of the South: The Music

Song of the South: The World Premiere

Song of the South: The Controversy

Song of the South: The Reviews

Song of the South: The Conclusion

Part Two: Secrets of the Song of the South

Film Credits

Story Summary

Short Biography of Joel Chandler Harris

Song of the South Dummies

The Brer Characters

Song of the South Actors That Never Were

Disney’s Uncle Remus Comic Strip

The Disney Uncle Remus Comic Strip That Never Was

The Song of the South Song

The Power of Words

Song of the South Book

That’s What Uncle Remus Said

Splash Mountain

Saturday Night Live Parody

Part Three: The Other Forbidden Stories—Sex, Walt, and Flubbed Films

Whatever Happened to Little Black Sunflower?

Disney’s Story of Menstruation

Disney Attacks Venereal Disease

Disneyland Memorial Orgy Poster Story

Jessica Rabbit: Drawn to Be Bad

Mickey Mouse Attempts Suicide

Walt’s Owl Nightmare

The Mickey Rooney Myth

J. Edgar Hoover Watches Walt

The Myth Of Walt’s Last Words

Walt Liked Ike

Disney’s Secret Commercial Studio

The Sweatbox: The Documentary Disney Doesn’t Want Seen

Tim Burton’s Real Nightmare at Disney

Disney John Carters That Never Were

Ward Kimball and UFOs

Walt’s Fantasy Failure: Baum’s Oz

Foreword

Had you visited a black home in the late forties, it would not be unusual to find a copy of Ebony magazine on the family coffee table. I never paid much attention to the monthly publication, but this particular issue caught my eye. A full-page photograph of actors James Baskett, Bobby Driscoll, and Luana Patten was featured next to an opinion piece on Walt Disney’s new motion picture Song of the South.

To the best of my knowledge, this was the first time in my young life that I took issue with a magazine’s editorial, and I regretted not having the writing chops to respond. Even though I was just a ten-year-old kid, I took issue with the editors for their unfair characterization of the film and of Walt Disney in particular. I had recently seen Song of the South at our local theater and found the movie delightful. Had they even seen the same film, I wondered?

Many years passed, and when this young artist and others arrived at the Walt Disney Studios in the fifties, we found ourselves having access to the coveted Disney vaults. This meant any movie we wanted to see was suddenly available for screening. Naturally, one of our first choices was Song of the South.

However, I took this a step further. Because employees were able to check out 16mm prints on occasion, I set up a special screening of the Disney film in a local Los Angeles church. The screening of the Disney motion picture proved insightful. The completely African-American audience absolutely loved the movie and even requested a second screening of the Disney classic.

I’ll admit I probably bring less baggage to the table than most. I was lucky enough to grow up in affluent, enlightened Southern California in the Forties and Fifties. My hometown of Santa Barbara was hardly the segregated South, and this unique environ-ment influenced my view of society. My parents and grandparents welcomed people of all colors into their home, so my perspective on race might not reflect the average African American’s view of society.

I am a cartoonist, not an academic, so this will not be an in-depth analysis of ethnic insensitivity. However, I have had the pleasure of speaking with filmmakers and animation old-timers about this rather touchy subject. It might be interesting to note that the funny images they put on paper and on the screen were there not to denigrate — but to entertain.

It’s a long time from Song of the South’s initial release and a maga¬zine’s strident editorial. Yet even today the film continues to be mired in controversy, and that’s a shame. I often remind people that the Disney movie is not a documentary on the American South.

The film remains a sweet and gentle tale of a kindly old gentleman helping a young child get through a troubled time. The motion picture is also flavored with some of the most inspired cartoon animation ever put on the screen. If you’re a fan of classic Disney storytelling, I guarantee you’ll not find a better film.

I survived three different managements at the Disney Company, beginning in the fifties when I worked as Disney’s first black animator and later as a storyman. My unexpected move upstairs to Walt’s Story Department was something I never anticipated. Not only was I privy to the Old Maestro’s story meetings, I had the unique opportunity to observe the boss in action. This included his management style and his treatment of subordinates. Not once did I observe a hint of the racist behavior Walt Disney was often accused of long after his death. His treatment of people — and by this I mean all people—can only be called exemplary.

Over the years, I worked in several different areas. For instance, I was given all sorts of assignments while working as a writer in Disney’s publishing department. One of my many assignments was to write what had become known as the Disney Holiday Story. These were comic strip continuities utilizing the Disney characters. Each of these stories would have a holiday theme and would run in newspapers from November to December 25, when the story would conveniently conclude on Christmas Day.

I had already written stories based on the standard Disney characters, including the wonderful 101 Dalmatians from the film of the same name. But I was getting bored with the typical holiday stuff, and wanted to try something new, different, and perhaps even a little dangerous. Could I possibly convince the powers-that-be at Disney to let me craft a story using the funny, clever, and outrageous characters from Song of the South?

As you might have imagined, Disney was skittish about raising any awareness of a movie it had been trying to bury for years. And, while Disney’s view of the South on which Joel Chandler Harris based his delightful stories might be considered naïve, it was never malicious or offensive.

Decades after its first release, I assumed we all lived in a more enlightened society. The Civil Rights battles of the sixties had been won, and people of color had taken their rightful place in society. Black people in motion pictures were no longer porters and maids. Funny, confident, and edgy performers like Eddie Murphy had replaced bug-eyed comedic actors like Mantan Moreland. It was now the eighties, and I hoped that Disney was willing to uncover the wonderful legacy it had kept hidden for so many years. Could delightful characters like Brer Rabbit, Brer Fox, and Brer Bear be enjoyed by a new generation? This was the question I would take to my bosses at Disney.

In the eighties, Disney was under a new forward-thinking management. Perhaps my timing was right, or maybe I just got lucky. In any case, I was given the go-ahead with my story entitled A Zip-A-Dee-Doo-Dah Christmas.

The story opens with the kids, Johnny and Ginny, coming to Uncle Remus with a problem. The chances of a snowfall in the South are pretty slim, they say. How can they truly enjoy Christmas without snow? This gives Uncle Remus the perfect opportunity to spin another of his Brer Rabbit tales. It seems the clever rabbit had a similar complaint, and his quest for a white Christmas led him into a world of trouble. Not surprisingly, that trouble involved another run-in with Brer Fox and Brer Bear. The story wraps up with Brer Rabbit escaping the clutches of his captors and learning his lesson about the real meaning of Christmas.

The story was submitted, and all appeared to be going well. I even removed the southern dialect from Uncle Remus, and allowed only the critters to retain their colorful dialogue. I was willing to give the illiterate former slave some “polish” as long as I could keep the rabbit, fox, and bear in character.

As you can imagine, the editors were aghast when they received the story. How could Disney submit such a racially insensitive story for publication? I wish I could have seen their faces when they were informed that the writer was black.

The story did end up running in newspapers in 1986, with no complaints. Keith Moseley penciled it and Larry Mayer inked it. Yet, four decades after it first premiered, Disney’s Song of the South was apparently still a very controversial topic. It remains so today, nearly sixty-five years after audiences first enjoyed it.

Why bury the wonderful performances of James Baskett, Hattie McDaniel, and Ruth Warrick? Why deny animation fans some of the finest cartoon animation to ever come out of the Disney Studios? Hearing the voice performances of Johnny Lee as Brer Rabbit and Nick Stewart as Brer Bear never fails to bring a smile to my face. America has come a long way since a little black kid sat in a movie theater in Santa Barbara and dreamed of a Disney career. Maybe it’s not too much to hope that the Disney Company might one day get over its self-imposed fears and finally find its own Laughing Place.

Introduction

This year I was a teaching a class of college students about how Disney tells stories three-dimensionally in its theme parks and resorts. During a break, a young lady came up to me to share how excited she was that, as her birthday present, her parents were taking her to see the theatrical stage production of Mary Poppins.

"That's wonderful," I replied. "Have you read the book?"

"There was a book?" she asked incredulously.

"Yes. There were several and some of the elements from them are incorporated into the musical," I responded.

"I just thought it was based on a really old movie," she said, with honest surprise.

I smiled while biting my lip. It took me a moment to realize that the movie Mary Poppins had premiered almost thirty years before she was born, so for her it was just another old movie. It was as much ancient history as when the dinosaurs walked the earth.

That experience was not unique. More and more, I interact with young people who have little or no knowledge of anything that happened beyond the last ten or twenty years, at most. Even worse, when I worked at Walt Disney World, I often saw executives who had little or no knowledge of Disney history nor any desire to know anything about Disney history if it conflicted with what they wanted to do.

I love Disney history.

I love the stories behind the stories. I love the little nooks and crannies that are rarely explored and often forgotten. I love knowing how and why something happened and how it affected other things. I love discovering and documenting these strange tales and sharing them with others.

I often tell people that you can love the Disney Brand, but still have concerns about how the Disney Business operates. Like many other large corporations, the Disney Company wants to control how its business is perceived by today's consumers, even if it means re-writing or eliminating parts of its own history.

The Disney Company has determined that the little stories in this book do not fit comfortably into today's larger story about the happy and magical world of Disney, where every corporate decision is always right. These stories are all true. They are not wild assumptions, rumors, urban myths, or revelations of scandalous activity. These stories are as well-documented as decades of research allow.

There is no need for salacious or sniggering text because the topics are controversial enough just by mentioning them in the first place. Heated emotions and lengthy passionate discussions can be conjured in mere seconds just by bringing up the subject of the Disney feature film Song of the South.

No official Disney book has even a single chapter that tells about the making of Song of the South. This book exists so that the history of Song of the South finally can be shared with all those interested in the film. Perhaps this information may even spark more intelligent discussions about the film in the future.

Some of the Song of the South material in this book first appeared in columns that I wrote over the years under my Wade Sampson pseudonym, as well as in a lengthy article I wrote for Hogan's Alley #16 (2009), a magazine about comic art. Much of my material has been liberally "borrowed" and used uncredited by others since then. Some of the other stories appear here because their topics alone would be considered inappropriate in a different historical collection.

It is not my intent to embarrass or annoy the Disney Company, but simply to record for Disney fans and researchers certain segments of Disney history that have never before been published. These stories, and so many others like them, are already being "lost" as times change, people die, and the Disney Company readjusts its history to make it more politically correct and appropriate for today's world.

Some people believe that certain history should be hidden or forgotten, that its artistic, technical, or historical value is far outweighed by its current inappropriateness. Other people believe that it is foolish and dangerous to censor history to fit current trends, that only by studying and discussing things now considered uncomfortable can we avoid making those same mistakes, and overcome ignorance.

As a Disney historian, I dance on the thin line between traditional academic scholarship and presenting material accessible to a more general audience. I have tried to incorporate references directly in the text rather than include a massive amount of footnotes that would distract from the flow of the story.

Please do not be fooled into believing that the stories in this book are the definitive versions. There is always more to tell about any story. I have discovered that, the moment I commit a story to print, suddenly a previously unknown anecdote or insight will magically appear to taunt me, despite decades of research.

The written word is thousands of years old and books were a treasure that provided a gateway to new knowledge and new discoveries. While many of you may be reading this on some electronic device, there is a joy that it also exists in a physical format so that it can be placed on a bookshelf next to other cherished paper companions.

Each individual chapter is a self-contained story, so feel free to open the book to any section and begin reading. Since I wrote these chapters to be read one at a time and savored, don't feel the need to gorge on the new information all at once. Think of the book as a box of chocolates with different delights and maybe some tasty hidden surprises to enjoy during a pleasant afternoon.

If you have half as much fun reading these stories as I have had writing them, then I had twice as much fun as you.

I hope you enjoy these stories. If you don't enjoy these stories, whatever you do, please don‘t throw me in the Briar Patch.

Jim Korkis

Jim Korkis is an internationally respected Disney historian who has written hundreds of articles about all things Disney for over three decades. He is also an award-winning teacher, a professional actor and magician, and the author of several books.

Korkis grew up in Glendale, California, right next to Burbank, the home of the Disney studios. As a teenager, Korkis got a chance to meet the Disney animators and Imagineers who lived nearby, and began writing about them for local newspapers.

In 1995, he relocated to Orlando, Florida, where he portrayed the character Prospector Pat in Frontierland at the Magic Kingdom, and Merlin the Magician for the Sword in the Stone ceremony in Fantasyland.

In 1996, Korkis became a full-time animation instructor at the Disney Institute teaching all of their animation classes, as well as those on animation history and improvisational acting techniques. As the Disney Institute re-organized, Jim joined Disney Adult Discoveries, the group that researched, wrote, and facilitated backstage tours and programs for Disney guests and Disneyana conventions.

Eventually, Korkis moved to Epcot as a Coordinator for the College and International Programs, and then as a Coordinator for the Epcot Disney Learning Center. He researched, wrote, and facilitated over two hundred different presentations on Disney history for Cast Members and for such Disney corporate clients as Feld Entertainment, Kodak, Blue Cross, Toys “R” Us, and Military Sales.

Korkis has also been the off-camera announcer for the syndicated television series Secrets of the Animal Kingdom; has written articles for several Disney publications, including Disney Adventures, Disney Files (DVC), Sketches, and Disney Insider; and has worked on many different special projects for the Disney Company.

In 2004, Disney awarded Jim Korkis its prestigious Partners in Excellence award.

A Chat with Jim Korkis

If you have a question for Jim Korkis that you would like to see answered here, please get in touch and let us know what's on your mind.

You began exceptionally early as a Disney historian. You were how old?

I was about 15 when I interviewed Jack Hannah with my little tape recorder and school notebook with questions printed neatly in ink. I learned to develop a very good memory because often when the tape recorder was running, people would freeze up. So, I sometimes turned off the tape recorder and just took notes which I later verified with the person. I always gave them a chance to review what they had said and make any changes. I lost a lot of great stories, although I still have them in my files for future generations, but gained a lot of trust.

How were able to hook up with these guys

I was very, very lucky. I was a kid, and it never occurred to me that when I saw their names in the end credits of the weekly Disney television show that I couldn't just find their names in the local phone book and call them up. Ninety percent of them were gracious, but there were about ten percent who thought it was a joke and that maybe one of their friends had put me up to phoning them.

It was like dominoes. Once I did one interview and the person was pleased, he put me in touch with others. After some of those interviews were published in my school paper and local newspapers, it gave me some greater credibility. Later, when they started to appear in magazines, I got even more opportunities.

How do you conduct your research?

JIM: You know, one of the proudest things for me about my books is that not a single factual error has been found.

To do my research, I start with all the interviews I've done over the past three decades, some of which are some available in the Walt's People series of books edited by Didier Ghezz. When necessary, I contact other Disney historians and authorities to fill in the gaps. And I have amassed a huge library of books, magazines, and documents.

When I moved from California to Florida, I brought with me over 20,000 pounds of Disney research material. The moving company that had just charged me a flat fee was shocked they had so severely underestimated the weight, and lost thousands of dollars. That was over fifteen years ago and the collection has only grown since that time.

About The Vault of Walt Series

You've been writing articles and columns about Disney for decades. Why all of a sudden start writing Vault of Walt books?

JIM: I was fortunate to grow up in the Los Angeles area at a time when I had access to some of Walt’s original animators and Imagineers. They shared with me some wonderful stories. I wrote articles about their for various magazines and “fanzines” of the time. All of those publications are long gone and often difficult to find today.

As more and more of Walt’s “original cast” pass away, I realized that their stories had not been properly documented, and that unless I did something, they would be lost. Everyone always told me I should write a book telling these tales and finally I decided to do it.

Walt's daughter Diane Disney Miller wrote the foreword to your first book. How did that come about?

JIM: She actually contacted me. Her son, Walter, loved the Disney history columns and articles I was writing and would send them to her. I was overwhelmed that she enjoyed them. She was appreciative that I tried to treat her dad fairly and not try to psycho-analyze why he did what he did.

She also liked that I revealed things she never knew about her father. As we talked and I told her I was doing the book, I asked if she would write the foreword. She agreed immediately and I had it within a week. She even invited me to go to the Disney Family Museum in San Francisco and give a presentation. She is an incredible woman.

What was Diane's favorite story in the book?

JIM: Obviously, the ones about her dad were a big hit. She especially liked the chapter about Walt and his feelings toward religion. She told me that it accurately reflected how she saw her dad act.

What's your favorite story in the book?

JIM: That’s like asking a parent to pick their favorite child. I tried to put in all the stories I loved because I figured this might be the only book about Disney I would ever write.

One chapter that I have grown to love even more since it was first published is the one about Walt’s love of miniatures. I recently found more information about that subject, and then on the trip to Disney Family Museum, I was able to spend hours examining some of Walt’s collection up close.

About Who's Afraid of the Song of the South?

Why did you decide to write a book about Song of the South?

JIM: I wanted to read a “Making of the Song of the South” book, but nobody else was ever going to write it. I wanted to know the history behind the production, why Walt made certain choices, and as many behind-the-scenes tidbits that could be told. I didn’t want to read a sociological thesis on racism.

Fortunately, over the years I had interviewed some of the people involved in the production, had seen the film multiple times, and had gathered material from pressbooks to newspaper articles to radio shows of the era.

There are a lot of misconceptions about Song of the South. I wanted to get the facts in print and let people make up their own minds.

Did you learn anything new when writing the book?

JIM: I thought I knew a lot after being actively involved in Disney history for over three decades, but writing this book showed me how little I really know.

For example, I learned that it was Clarence Nash, the voice of Donald Duck for decades, who did the whistling for Mr. Bluebird on Uncle Remus’ shoulder. I learned that Ward Kimball used to host meetings of UFO enthusiasts at his home. I learned that the Disney Company tried for years to make a John Carter of Mars feature. I learned that Walt himself tried to make a sequel to The Wizard of Oz. I learned that Disney operated a secret studio to make animated television commercials in the mid-1950s to raise money to build Disneyland. And so much more.

Even the most knowledgeable Disney fans will find new treasures of information on every page of this book.

What's the biggest takeaway from the book?

JIM: Walt Disney was not racist. That is one of those urban myths which popped up long after Walt died, and so he was unable to defend himself.

In my book, I make it clear that Walt had no racist intent at all in making Song of the South. He merely wanted to share the famous Uncle Remus stories that he enjoyed as a child, and he treated the black cast with respect and generosity.

Many people don't realize that the events in the film take place after the Civil War, during the Reconstruction. So many offensive Hollywood films made at the same time as Song of the South, even one with little Shirley Temple, depicted the Old South during the Civil War in an unrealistic manner. Walt's film got lumped in with them, and he was a visible target for a much larger crusade.

Books by Jim Korkis:

- The Vault of Walt: Volume 3 (2014)

- Animation Anecdotes: The Hidden History of Classic American Animation (2014)

- Who's the Leader of the Club? Walt Disney's Leadership Lessons (2014)

- The Book of Mouse: A Celebration of Walt Disney's Mickey Mouse (2013)

- Who's Afraid of the Song of the South? And Other Forbidden Disney Stories (2012)

- The Vault of Walt: Volume 2 (2013)

- The Vault of Walt: Volume 1 (2012)

With John Cawley:

- Animation Art: Buyer's Guide and Price Guide (1992)

- Cartoon Confidential (1991)

- How to Create Animation (1991)

- The Encyclopedia of Cartoon Superstars: From A to (Almost) Z (1990)

In this excerpt, from the "Disneyland Memorial Orgy Poster Story", Jim writes about legendary comic book artist Wally Wood's pornographic portrayal of Disney characters, in action:

From a distance, or at a quick first glance, the infamous "Disneyland Memorial Orgy" poster appears to be a typical cartoon of a host of Disney animated characters frolicking in a forest with a castle in the background. However, closer examination reveals that the beloved characters are involved in very un-Disneylike activities, from extreme sex to drug use.

Time magazine's Richard Corliss described the poster:

In Wally Wood's lushly scabrous "Disneyland Memorial Orgy", a 1967 parody that ran in The Realist magazine, Walt's creatures behaved exactly as barnyard and woodland denizens might. Beneath dollar-sign searchlights radiating from the Magic Kingdom's castle, Goofy had his way with Minnie, Dumbo the flying elephant dumped on Donald Duck, the Seven Dwarfs besmirched Snow White en masse, and Tinker Bell performed a striptease for Peter Pan and Jiminy Cricket. Mickey slouched off to one side, shooting heroin.

Paul Krassner, who created the underground satirical newspaper The Realist in 1958, had worked in the same office building that housed Bill Gaines' MAD magazine, and had sold a couple of submissions to Gaines. Contributors to The Realist (which published its last issue in spring 2001) included Lenny Bruce, Jules Feiffer, Norman Mailer, and Richard Pryor.

Krassner remembered:

After Walt Disney died (in 1966), I somehow expected Mickey Mouse, Donald Duck and the rest of the gang to attend his funeral, with Goofy delivering the eulogy and the Seven Dwarves serving as pallbearers. Disney‘s death occurred a few months after Time magazine's famous "Is God Dead?" cover, and I realized that Disney had served as god to that whole stable of imaginary beings who were now mourning in a state of suspended animation. Disney had been their creator, and had repressed their baser instincts, but now with his departure, they could finally shed their cumulative inhibitions and participate together in an unspeakable Roman binge, to signify the crumbling of an empire.

I contacted Wally Wood, who had illustrated my first article for MAD ("If Comic Strip Characters Answered Those Little Ads in the Back of Comic Books") and he (anonymously) un-leashed their collective libido, demystifying an entire genre in the process. I told Wally my idea, without being specific. In a few months, he presented me with the artwork, unsigned. I paid him $100. The "Disneyland Memorial Orgy" was a Realist center spread (May 1967 issue in black and white) that became our most infamous poster. The "Disneyland Memorial Orgy" center spread became so popular that I decided to publish it as a poster in 1967.

Wally Wood was a legendary comic book artist whose work continues to be collected and studied today, especially his early efforts for EC comic books. He was the perfect choice to do the artwork for two reasons.

First, since the mid-1950s, Wood had worked at MAD magazine drawing parodies of Disney characters for some of the articles. For instance, in the December 1956 issue of MAD (#30), Wood drew a wonderful six-page satire of the Disneyland weekly television show entitled "Walt Dizzy Resents Dizzyland". Many of the Disney animated characters that would later appear on the notorious poster, including Mickey Mouse, Donald Duck, Dumbo, and the Seven Dwarfs, first appear in this piece.

Second, Wood had been earning extra income by supplying softcore cartoons for men's magazines like Gent, The Dude, and Nugget, and was no stranger to that type of subject matter. In the 1970s, Wood pursued this market even further, with contributions to Al Goldstein's Screw magazine as well as adult parodies inspired by Disney fairy tales entitled "Malice in Wonderland" and "Slipping Beauty".

An inside source at Disney supposedly told editor Paul Krassner that the company chose not to sue to avoid drawing attention to what ultimately could be a losing battle. Since Krassner jobbed out his printing and had no capital investment nor any assets that Disney could garner, it wasn't worth their effort. It also did not make sense at the time (just months after the death of Walt) to create further public embarrassment and get nothing in return.

In those days, this was not an unusual tactic for the Disney legal department when they felt that the infringement would be seen only by a small segment of its audience, and then quickly forgotten and thrown away as new issues of the periodical were published. For example, the September 1970 issue of National Lampoon magazine featured a cover of a classic 1930s-style Minnie Mouse flashing her bare top and revealing her small breasts covered with flower pasties. The editors purposely published the cover in the hope that it would stir the ire of Disney and bring some publicity to their fledgling new magazine. Disney chose to ignore it, and indeed the cover was quickly forgotten.

In May 2005, Krassner told the L.A. Weekly:

In Baltimore, a news agency distributed that issue [of The Realist] with "Disneyland Memorial Orgy" removed; I was able to secure the missing pages, and offered them free to any reader who had bought a partial magazine. In Oakland, an anonymous group published a flyer reprinting a few sections of the center spread and distributed it in churches and around town.

Krassner claimed that the original art for the "Disneyland Memorial Orgy" was stolen from the printer.

There were several pirated editions of the poster available during the 1970s. One of these editions was done in a vertical format (rather than the original horizontal format) and made crude alterations and additions to Wood's art. Even today, images from the original Wood artwork have been illegally used for everything from T-shirts to tattoos.

Disney was not so reluctant to assert its rights when entrepreneur Sam Ridge pirated the drawing and sold it as a black-light poster. The commercial nature of the bootleg, and the fact that it would reach a much larger audience than the poorly distributed Realist, prompted Disney to file a lawsuit, which was settled out-of-court and forced Ridge out of business.

In this excerpt, Jim recounts the hilarious but uncomfortable parody of Walt Disney, and in particular Song of the South, on an episode of Saturday Night Live:

To poke fun at the controversy surrounding Disney's Song of the South, the long-running, popular NBC sketch comedy show Saturday Night Live aired an original cartoon on its April 15, 2006, episode.

Saturday TV Funhouse, the name of a recurring, short, animated segment created by longtime SNL writer Robert Smigel, often satirized public figures and corporations. Disney had sometimes been a target of this satire.

The April episode was designed to resemble a typical Disney commercial that invited two children to take a journey into the Disney Vault, where Disney's animated features are stored when they are removed from general release to the public.

Once inside the Vault, the children discover other things that Disney wants kept secret. One of them picks up a video:

Boy: "I've never heard of this one…Song of the South?"

Mickey Mouse: "Ohh, nobody wants to see that one anymore!"

Girl: "How bad could it be?"

Mickey Mouse: "It's the very original version that he [Walt Disney] only played at parties."

An actual clip from the film of Uncle Remus walking through an animated background is shown, but with a newly dubbed soundtrack of lyrics to the famous song:

Uncle Remus: "Zip-A-Dee-Doo-Dah, Zip-A-Dee-Ay…Negroes are inferior in every way; whites are much cleaner, that's what I say; Zip-A-Dee-Doo-Dah, Zip-A-Dee-Ay."

The episode satirized the belief that Song of the South is hidden deep in the Vault because of its racism, and it was made in response to the March 10, 2006, Disney shareholder meeting held a month earlier. At the meeting, Disney Company President and CEO Bob Iger stated that the film was not released on its 60th anniversary that year because he had concluded that its "depictions…would be bothersome to a lot of people. … Even considering the context [in which] it was made, I had some concerns about it."

About Theme Park Press

Theme Park Press is the world's leading independent publisher of books about the Disney company, its history, its films and animation, and its theme parks. We make the happiest books on earth!

Our catalog includes guidebooks, memoirs, fiction, popular history, scholarly works, family favorites, and many other titles written by Disney Legends, Disney animators and artists, Mouseketeers, Cast Members, historians, academics, executives, prominent bloggers, and talented first-time authors.

We love chatting about what we do: drop us a line, any time.

Theme Park Press Books

The Unauthorized Story of Walt Disney's Haunted Mansion The Ride Delegate 501 Ways to Make the Most of Your Walt Disney World Vacation The Cotton Candy Road Trip The Wonderful World of Customer Service at Disney Disney Destinies Disney Melodies The Happiest Workplace on Earth Storm over the Bay A Historical Tour of Walt Disney World: Volume 1 Mouse in Transition Mouseketeers Down Under Murder in the Magic Kingdom Walt Disney and the Promise of Progress City Service with Character Son of Faster Cheaper A Tale of Two Resorts I Saw Ariel Do a Keg Stand The Adventures of Young Walt Disney Death in the Tragic Kingdom Two Girls and a Mouse Tale Ears & Bubbles The Easy Guide 2015 Who's the Leader of the Club? Disney's Hollywood Studios Funny Animals Life in the Mouse House The Book of Mouse Disney's Grand Tour The Accidental Mouseketeer The Vault of Walt: Volume 1 The Vault of Walt: Volume 2 The Vault of Walt: Volume 3 Who's Afraid of the Song of the South? Amber Earns Her Ears Ema Earns Her Ears Sara Earns Her Ears Katie Earns Her Ears Brittany Earns Her Ears Walt's People: Volume 1 Walt's People: Volume 2 Walt's People: Volume 13 Walt's People: Volume 14 Walt's People: Volume 15

Write for Theme Park Press

We're always in the market for new authors with great ideas. Or great authors with new ideas. Whichever type of author you are, we'd be happy to discuss your book. Before you contact us, however, please make sure you can answer "yes" to these threshold questions:

Is It Right for Us?

We specialize in books that have some connection to Disney or theme parks. Disney, of course, has become a broad topic, and encompasses not just theme parks and films but comic books, animation, and a big chunk of pop culture. Your book should fit into one (or more) of those broad categories.

Is It Going to Make Money?

There's never a guarantee that any book will make money, but certain types of books are less likely to do so than others. They include: hardcovers, books with color photos, and books that go on forever ("forever" as in 400+ pages). We won't automatically turn down these types of books, but you'll have to be a really good salesman to convince us.

Are You Great to Work With?

Writing books and publishing books should be fun. The last thing you want, and the last thing we want, is a contentious relationship. We work with authors who share our philosophy of no drama and zero attitude, and the desire for a respectful, realistic, mutually beneficial partnership.

If you said "yes" three times, please step inside.