- Visit the Imagineering Graveyard

- Now Sailing: "Skipper Stories" - Tales from the Jungle Cruise

- Coming Soon: The biography of Disney animator Jack Hannah

- Coming Soon: A Haunted Mansion anthology

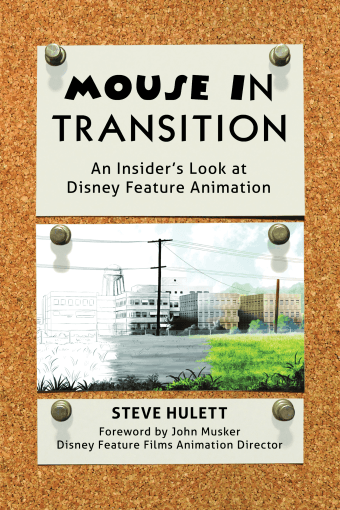

Mouse in Transition

An Insider's Look at Disney Feature Animation

by Steve Hulett | Release Date: December 4, 2014 | Availability: Print, Kindle

AN INSIDER'S LOOK AT DISNEY FEATURE ANIMATION

When Walt Disney died, the studio went into a creative lockdown. The mantra "What Would Walt Do" comforted the old-timers, but it shackled the up-and-comers who wanted to take big risks on new approaches to animation.

Into this sleepy studio walked Steve Hulett, whose father Ralph had been an artist at the studio for nearly four decades. Hulett was hired as a storyman during a transitional time in the company's history, when Walt's spirit was receding and Hollywood kingpins Michael Eisner and Jeffrey Katzenberg were taking over.

Hulett takes you into the sometimes dark Disney heart of power, politics, and the cult of personality as he recalls:

- Helping Ken Anderson on the ill-fated feature Catfish Bend, and how Anderson in return tried to get him fired

- Enduring intense, marathon story meetings with Woolie Reithermann, which Hulett recounts in colorful, unexpurgated detail

- Working on such Disney features as The Fox and the Hound, The Great Mouse Detective, and The Black Cauldron

- Meeting Eisner and Katzenberg for the first time, and the seismic shock their edicts sent through the Disney Studio

- Learning the ropes through candid conversations with such Disney luminaries as Ward Kimball, Claude Coats, and Eric Larson

Hulett's wit and dry humor, coupled with his first-hand accounts of working side-by-side with Ken Anderson, Woolie Reitherman, John Lasseter, and Little Mermaid co-director/writer John Musker (who wrote the foreword), provides unique and unprecedented insight into the rapidly changing Disney Studio of the 1970s and 1980s.

Table of Contents

Foreword

01Getting Hired

02Larry Clemons

03The Disney Animation Story Crew

04And Then There Was...Ken!

05Hard Deadlines and the Marathon Meeting of Woolie Rietherman

06Disney Print Work...and a Window into Hyperion

07Disney Departures

08Voice Actors

09The CalArts Brigade...and Tilting at Windmills

10Swords, Sorcerers, and Horned Kings

11Rodent Detectives and Studio Strikes

12Development, Dead Ends, and Lucrative Side Roads

13“Basil” Kicks into High Gear

14Change Sweeps Over Walt Disney Productions

15The Arrival of Jeffrey Katzenberg

16Moves and Changes

17Headquartered in Glendale

18The Arrival of Peter Schneider

19Mr. Gombert’s Magical Memo

Appendices

AInterviews: The Hyperion Studio Brigade

BA Star Is Drawn: The Making of “Pinocchio”

CWalt Disney Productions Feature Animation Staff: 1970s/1980s

Foreword

The tall, tan, rangy dude draped his long frame into a Kem Weber chair in my Disney Studio office, plopped his feet up on my desk, and broke into a crinkly grin: ”Yeah…I freely admit…I’m a nep!”

The date was circa 1980. The speaker was one Steve Hulett, son of Ralph Hulett, a veteran background painter at the Walt Disney Studio during its heyday (thus accounting for Steve’s self-proclaimed “nep” status). Steve was also that most rare of employees in a company full of draftsmen, painters, and designers. He was a writer! He could talk about the film at hand and could produce reams of dialogue for it, but he could also natter on about current studio gossip, as well as breezily recount Old Hollywood anecdotes gleaned from a lunch with screenwriter Niven Busch. I didn’t realize at the time, though, that all the while he was doing this, Steve was also filing away anecdotes of this New Hollywood, the Disney Animation Studio of the late seventies and eighties, which he retells drily in the pages ahead.

I toiled in the trenches with Steve. I was a fellow arteest at the Mouse House during the years he wittily describes in this memoir. We worked on some films like The Fox and the Hound where I, as an animator, had no contact with the writerly world of “story” that Steve inhabited. We worked together on other films, like Black Cauldron and Great Mouse Detective (which really should have been known by its original title, Basil of Baker Street, but you’ll get the sordid details from Steve a few chapters in) where I, in my new role as a director (and story man) toiled side by side with Mr. Hulett, doing battle with people who didn’t always share our enlightened point of view about the storytelling in these films. We have matching scars to prove it.

This book is entitled “Mouse in Transition” and that’s a good title, although there are other “t” words that can also be used to describe this time at the Disney Animation Studio: “tumultuous”, “tense” (at times), and “turbulent”. The seventies and eighties at Disney saw tremendous upheavals, particularly volcanic coming after years of relative torpor. Veterans were retiring, new kids arriving, passed over folks in the middle frustrated, civil wars within, threatened hostile takeovers without. And an ill-advised strike that was founded on the powerful position: “If you keep sending the work we do overseas, we’re not going to do it anymore…” Hmmmm…

Steve pens a pretty accurate portrait, to the squinty eyes of my memory, of the people and the politics of the day. The insecurity of the Studio itself and the artists who staffed it at that time comes through pretty strongly in Steve’s telling.

Most special to me are Steve’s portraits of some of the artists I worked with and learned from, and occasionally clashed with. People who haven’t gotten the notice that some of their more celebrated confreres did, but who were an essential part of the fabric of Disney during this time. Mentors like Vance Gerry. Wags like Ed Gombert. And floating over the entire narrative, the complex figure of the forgotten man, Steve’s best friend, collaborator, and guide through the thicket of Studio politics: Pete Young. Pete was a talented, tormented artist and political animal, and a sensitive storyteller whose gag drawings were funnier than anything in most of the movies he worked on. Steve’s evolving relationship with Pete is the emotional spine of this work.

I hope you enjoy Steve’s puckish parade of long suffering “creatives”, narcissists, and neurotics (I count myself among their number) as much as I did. Egos and artists are part of what made the Disney Studio and its films unique. Working at the Mouse House during these years could be maddening. It could be frustrating. But it also could be rewarding, and God help us, fun.

Steve Hulett

Steve Hulett spent a decade in Disney Feature Animation’s story department writing animated features, first under the tutelage and supervision of Disney veterans Woolie Reitherman and Larry Clemmons, then under the watchful eye of young Jeffrey Katzenberg.

While at Disney, he worked on such features as The Fox and the Hound, The Great Mouse Detective, and The Black Cauldron.

Since 1989, Hulett has served as Business Representative of The Animation Guild and Affiliated Optical Electronic and Graphic Arts, Local 839 IATSE (fka Motion Picture Screen Cartoonists), the animators’ union.

This is his first book.

A Chat with Steve Hulett

Coming soon...

In this excerpt, Steve Hulett relates his first meeting with Michael Eisner at the Disney Studio, with cameo by Roy Disney.

Michael Eisner lounged his six-foot-four frame in a conference room chair. He was wearing jeans and sweatshirt, but why not? It was a Saturday morning. Animation directors and story artists, all in their twenties and thirties, sat at a long table on three sides of him. Mr. Eisner’s big German shepherd noshed a rawhide strip in a corner of the room.

We had been called to this meeting with the new CEO because he wanted to find out about us, to pick our brains, to chitchat. A dozen of us sat stiffly in chairs, waiting for his questions. None of the questions were tough; things like “How long we have you worked at Disney?”…“What do you do, exactly?”…“Where do you think animation should go?” came out of his mouth, but we were uptight just the same. This was the Big Man, fresh from Paramount.

Pete Young was among the first to get quizzed.

“So, what’s your name?”

Pete told him.

“So how long have you been at the studio, Peter?

“Since 1970.”

A startled look. “1970?! How old were you when you started here? Fourteen?”

It was an obvious question. Pete looked like he was maybe a year out of college if you didn’t focus on the little highlights of gray in his thick, curly hair. His face was young and unlined. He resembled a choirboy who knew a few secrets.

“Twenty-three.”

Michael Eisner said that was hard to believe, and then went on around the table, asking more questions. When he came to me, I told him I had been at the studio since 1976 and was a semi-nepot. He asked what that meant. I explained that my father had worked at Disney’s as a background artist from the Hyperion days to the early seventies, but had died before I applied for the job. Therefore, I called myself a semi rather than full-fledged nepot.

Michael Eisner grinned. “Hey, I’ve got kids. I like to think I’ll help THEM get a job when the time comes.”

The questioning went on. Tad Stones got into a polite debate with Michael about the kind of animated features the company should make. Mr. Eisner didn’t appear to take offense, but I sure as hell wouldn’t have argued with the chief executive of the company, not on the first meeting.

When Michael E. had worked his way around the table, he explained his philosophy of movie making:

You need a solid idea. And then you need to execute that idea well. Fish-out-of-water stories are good, but you need some twist. Beverly Hills Cop was a fish-out-of-water story. We took a street cop from the ghetto and put him in the most different kind of place we could think of. What could be more different than Rodeo Drive and Beverly Hills? You’ve got fancy stores and big mansions. You’ve got the Beverly Hills Police Department. Audiences loved the picture and it made a fortune. The thing was a fresh idea, you know? And it was well executed, with a good script, good cast, a good director. It’s what we’re going to do around here. It’s what we’ll be doing with animation.

The new CEO had definite ideas about animated features. They had to change from what they had been as far as he was concerned, had to be modern and “with it”, had to tackle new subjects. Nobody except Tad argued with him.

In the first months of the Eisner regime, word circulated that Michael E. and company wanted to outsource most Disney animation to Korea and Taiwan. Many cartoon staffers figured that they would be looking for other employment soon, as the work at Walt Disney Productions would be gone. After awhile, I got tired of the rumors, tension, and suspense. Roy Disney had a new office on the third floor of the Animation Building, and I paid it a visit, hoping to find out what was REALLY going on.

Roy’s office space wasn’t large, but it already had his personal stamp: Model ships. Wood paneling. Framed pictures of sailboats on the walls. And there was a poster for a documentary Roy had made titled Pacific High hanging near the door. The poster’s graphics and layout led me to believe the movie was about a long sea voyage through the South Pacific.

Roy was sitting behind a wooden desk and came out from behind it to greet me. He looked a lot like his Uncle Walt, with the same moustache, same parted hair. He was low-key and self-effacing, but seemed fully aware of his place in the corporate structure. He had engineered the coup against Ron Miller, after all, and knew what his power and leverage were. He was dressed in a sweater and open-necked shirt, and puffed energetically on a cigarette. Also like Walt.

I asked him point-blank if Michael Eisner and Frank Wells were planning to get rid of the Animation Department. He took a long draw on his cigarette.

“They talked about it. They wondered why everything couldn’t be outsourced to Asia. I told them animation was the center of the company. That it needed to KEEP being the center of the company.”

“So, then, the department’s staying together?”

“Think so. I told Frank and Michael I wanted to head up animation. They thought that was a doable idea.”

What changes were coming, I asked him. He said he didn’t know. Was the department going to grow? Shrink? He answered that he thought they wanted to do more features, maybe one a year.

I couldn’t think of anything more to ask, thanked him for his time, and walked to the door. I pointed at the Pacific High poster and mentioned that William F. Buckley had written a book called Atlantic High, also about sailing. Roy grimaced.

“Buckley, the son of a bitch. The documentary came out before his damn book. And so one day he calls me up and says: ‘Roy? I’ve got a memoir of a sailing trip coming out and I’m titling it Atlantic High. That’s all right with you, isn’t it?’ It wasn’t, but I say, ‘Whatever you want to do, Bill.’ I didn’t yell at him, but he’s still an S.O.B.”

Don’t mess with sailors.

Continued in "Mouse in Transition"!

In this excerpt, Steve Hulett recounts one of many examples of how Eisner and Katzenberg shattered the collegial calm of the sleepy Disney Studio.

Roy Disney was the new head of the animation division. He wasn’t in the Flower Street building every day, but when he came in he made a point to review Pete’s work and give input. Pete was a good soldier and incorporated Roy’s suggestions into the boards, even ones he didn’t wholeheartedly embrace.

Weeks later an official announcement for the production supervisors of Oliver came down: George Scribner and Rick Rich (one of The Black Cauldron directors) were the helmers for the picture, and Pete Young was story director.

The relaxed atmosphere of the “old” Disney whipped away like leaves in a stiff autumn wind. The pace of work picked up, and Pete was under more stress than ever. I had the feeling he wasn’t thrilled with some of Roy’s input, though he didn’t admit it in so many words. But his tight mouth and blank stares into space were giveaways.

In another part of the building, Tad Stones was developing a featurette starring Goofy; Michael and Jeffrey [Katzenberg] came to Glendale one day to look at the boards and proclaimed them “great”, but three days later put the featurette on hold. That prompted director Ron Clements to observe to me in a hallway: “You know, these new guys are interesting. When they see something and say ‘This is the most FABULOUS thing we’ve ever seen!’ that means ‘Maybe this is sort of okay, and maybe we’ll put it in production.’”

Without warning, staff writer Tony Marino was laid off. Tony had been at the studio for years, and I’d always considered him a barometer for the health of my own Disney career. If Mr. Marino was still on the payroll, my job was secure. But if not? I could feel my stomach knot up as soon as I got the news. Pete came out of his dark mood long enough to chide me: “You better watch your step, Hulett. Tony was the canary in the coal mine. And Tony’s now lying on the bottom of his cage.”

Work on Oliver continued on. Roy came up with an idea that Fagin and his gang of thieving dogs would steal a valuable panda from the city zoo. I thought the idea was lame; Pete was miffed that I wasn’t enthusiastic about it. But I wasn’t the story director and had a hard time faking support.

The main lot communicated that Mr. Katzenberg and Mr. Eisner wanted to see the Oliver story-beat boards, front to back, on the following Saturday. Later on, Jeffrey Katzenberg would perform this task solo, but in those early days Jeffrey and Michael Eisner used a team approach.

Pete worked feverishly to get the boards in shape. He worked late. He worked through lunch. He worked, tense and exhausted, all through the last weekend. And when the appointed Saturday rolled around, Pete was in the building alone to pitch the beat boards, complete with all of Roy Disney’s story suggestions.

Only Roy wasn’t there, and Michael and Jeffrey made no bones about hating the boards. They hated the panda, they hated a lot of the story progression, they hated almost everything that wasn’t Charles Dickens. When I came in Monday morning, Pete told me about the disaster: “Jeffrey and Michael ripped the boards to shreds. The panda they didn’t get at all. There wasn’t one big story point they got behind. So…we’re screwed.”

I told him we could fix it. He shrugged his shoulders, face drawn. His eyes looked like two dark holes punched in a snowbank.

“Maybe. But who knows?” He shrugged again. “Just when you think you have job security, you find out you don’t.”

I knew what was going through his brain because the same things were going through mine: When you do everything you’re asked to do and still get the shaft, what’s left? Nothing but the powdery ashes from the weeks and months of story work.

So we started to reconstruct the boards without a panda, without the zoo sub-plot. Pete came up with two new characters, a pair of fierce-looking Dobermans that were Fagin’s enforcers, and story development staggered forward.

But Pete’s heart was no longer in it. He was funny and sardonic like always, but he was also distant. When I threw an idea out in an impromptu office story meeting, Pete would tilt his head, shrug, and say: “Sure, why not? That’s as good to put in as anything.”

Meanwhile, Basil of Baker Street was rolling into its last lap. Most of the sequences had been tied down and a lot of animation had been completed. Burny Mattinson held a screening of the picture for the story crew and directors to see if anybody had any late tweaks or suggestions. Roy was in attendance, and when the lights came up, he looked at all of us and said:

“Lots of good stuff here, but you need to switch sequence one with sequence two.”

Burny looked at him blankly. “Switch sequences?”

“Reverse one and two. Get to the action faster. It’ll work fine.”

People nodded, looking a bit dazed. Burny grunted. And Roy walked out. There was a long stretch of silence. Finally Burny said:

“What is Roy thinking? We can’t change the story order. The story won’t make any SENSE.”

Everyone agreed that swapping sequences made the movie incoherent. The solution? Burny and the directors didn’t change anything. And Roy never brought up the subject again.

A little while later, I found out that Burny had another issue. He and I were sitting around after a board presentation and he groused: “I’ve worked hard to keep Basil’s budget under control, and I just discovered that $500,000 got shifted off Oliver on to us.”

“Us” in this case was Basil of Baker Street.

“Magic studio accounting,” I said.

“Yeah, but it’s still irritating.”

Continued in "Mouse in Transition"!

About Theme Park Press

Theme Park Press is the world's leading independent publisher of books about the Disney company, its history, its films and animation, and its theme parks. We make the happiest books on earth!

Our catalog includes guidebooks, memoirs, fiction, popular history, scholarly works, family favorites, and many other titles written by Disney Legends, Disney animators and artists, Mouseketeers, Cast Members, historians, academics, executives, prominent bloggers, and talented first-time authors.

We love chatting about what we do: drop us a line, any time.

Theme Park Press Books

The Unauthorized Story of Walt Disney's Haunted Mansion The Ride Delegate 501 Ways to Make the Most of Your Walt Disney World Vacation The Cotton Candy Road Trip The Wonderful World of Customer Service at Disney Disney Destinies Disney Melodies The Happiest Workplace on Earth Storm over the Bay A Historical Tour of Walt Disney World: Volume 1 Mouse in Transition Mouseketeers Down Under Murder in the Magic Kingdom Walt Disney and the Promise of Progress City Service with Character Son of Faster Cheaper A Tale of Two Resorts I Saw Ariel Do a Keg Stand The Adventures of Young Walt Disney Death in the Tragic Kingdom Two Girls and a Mouse Tale Ears & Bubbles The Easy Guide 2015 Who's the Leader of the Club? Disney's Hollywood Studios Funny Animals Life in the Mouse House The Book of Mouse Disney's Grand Tour The Accidental Mouseketeer The Vault of Walt: Volume 1 The Vault of Walt: Volume 2 The Vault of Walt: Volume 3 Who's Afraid of the Song of the South? Amber Earns Her Ears Ema Earns Her Ears Sara Earns Her Ears Katie Earns Her Ears Brittany Earns Her Ears Walt's People: Volume 1 Walt's People: Volume 2 Walt's People: Volume 13 Walt's People: Volume 14 Walt's People: Volume 15

Write for Theme Park Press

We're always in the market for new authors with great ideas. Or great authors with new ideas. Whichever type of author you are, we'd be happy to discuss your book. Before you contact us, however, please make sure you can answer "yes" to these threshold questions:

Is It Right for Us?

We specialize in books that have some connection to Disney or theme parks. Disney, of course, has become a broad topic, and encompasses not just theme parks and films but comic books, animation, and a big chunk of pop culture. Your book should fit into one (or more) of those broad categories.

Is It Going to Make Money?

There's never a guarantee that any book will make money, but certain types of books are less likely to do so than others. They include: hardcovers, books with color photos, and books that go on forever ("forever" as in 400+ pages). We won't automatically turn down these types of books, but you'll have to be a really good salesman to convince us.

Are You Great to Work With?

Writing books and publishing books should be fun. The last thing you want, and the last thing we want, is a contentious relationship. We work with authors who share our philosophy of no drama and zero attitude, and the desire for a respectful, realistic, mutually beneficial partnership.

If you said "yes" three times, please step inside.