- Visit the Imagineering Graveyard

- Now Sailing: "Skipper Stories" - Tales from the Jungle Cruise

- Coming Soon: The biography of Disney animator Jack Hannah

- Coming Soon: A Haunted Mansion anthology

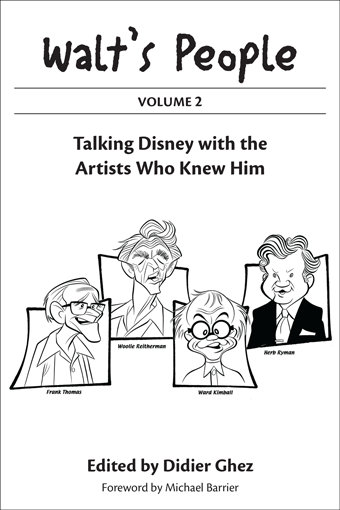

Walt's People: Volume 2

Talking Disney with the Artists Who Knew Him

by Didier Ghez | Release Date: February 20, 2015 | Availability: Print, Kindle

Disney History from the Source

The Walt's People series is an oral history of all things Disney, as told by the artists, animators, designers, engineers, and executives who made it happen, from the 1920s through the present.

Walt’s People: Volume 2 features appearances by Friz Freleng, Grim Natwick, Frank Tashlin, Ward Kimball, Floyd Gottfredson, Herb Ryman, Frank Thomas, Dale Oliver, Eric Larson, Woolie Reitherman, Richard Rich, and Glen Keane.

Among the hundreds of stories in this volume:

- WARD KIMBALL talks Disney trains, how he got hired at Disney, his studio pranks, his drug use, why no major Disney character is a cat, and why Walt wouldn't let him order the beef stew.

- FLOYD GOTTFREDSON discusses in detail his work on the Mickey Mouse comic strip, his cartooning techniques, how the Mickey cartoon character evolved stylistically, and his opinion of Walt Disney.

- ERIC LARSON shares what it was like to work at the Disney studio for over five decades, his efforts to train new animators to replace the old, and his experiences as one of Walt's "Nine Old Men".

- FRANK THOMAS, another of Walt's' Nine Old Men, relates the highlights of his career with Disney, and his lifelong collaboration with fellow Disney animator Ollie Johnston.

The entertaining, informative stories in every volume of Walt's People will please both Disney scholars and eager fans alike.

Table of Contents

Foreword

Introduction

Friz Freleng by J.B. Kaufman

Grim Natwick by John Province

Frank Tashlin by Michael Barrier

Ward Kimball by Jim Korkis

Ward Kimball by Michael Barrier

Floyd Gottfredson by Arn Saba

Herb Ryman by Robin Allan

Frank Thomas by Christian Renaut

Dale Oliver by Wes Sullivan

Eric Larson by Robin Allan

Eric Larson by Thorkil B. Rasmussen

Woolie Reitherman by Thorkil B. Rasmussen

Richard Rich by Christian Renaut

Richard Rich by Didier Ghez

Glen Keane by Didier Ghez

Glen Keane by Michael Lyons

Further Reading

About the Authors

Foreword

I can’t lay my hands on it, but I remember reading, not long ago, a newspaper article that reassured me about the value of interviews with people who worked for Walt Disney and sometimes saw him daily.

The point of the article was that our memories are not like tape recordings or reels of film. We don’t simply store away what we see and hear—each memory waiting to be brought back to life with the right cue. Instead, memories tend to be strong and reliable according to how useful they will be to us in the future. And what memories could be more useful to someone working at a studio like Walt Disney’s than strong, clear memories of the boss?

Time and again, in interviewing people who worked for Walt Disney, I’ve been struck by how intently they observed him. They stored up memories, not so that they could tell their grandchildren what it was like to work for a genius, but so they could avoid having that genius slap them down the next time they showed him a storyboard or some rough animation. What they remember about their co-workers may be vague or demonstrably inaccurate, but their memories of Walt have a sharp, clear edge.

Walt’s people were attuned not just to his smiles and frowns, but also to the patterns of his finger tapping on the arm of his chair. They thought they could tell when he was pleased, when he was impatient, and when he was really angry. But, of course, not everyone interpreted his finger tapping, or anything else about him, in exactly the same way. He wasn’t an easy “read” for anyone. David Hand—my interview with him is in the first volume in this series—studied Disney very carefully, and for the most part successfully, to the point that he became Walt’s second in command, but eventually even he slipped from the high wire.

In later years, Walt’s inscrutability and unpredictability grew. It seemed to one man who worked for Walt as a contractor during these years that his employees were terrified of him. I sometimes wonder, in reading interviews with people who experienced such fear at some point in their Disney careers, why so many of them stayed, often until Walt threw them out. The answer, I think, is that Walt Disney always wanted to surrender himself to some kind of work that absorbed him totally. At different points in his life, he found that absorbing work in animation, in his theme park, and finally in his scheme for a city of the future. To be around someone who thinks and acts in such grand terms is always stimulating, whatever the ultimate merits of particular projects, and Walt’s energy was particularly attractive.

Working for Walt, you must have felt a little more alive. Frightened, maybe, but alive, and certainly aware. That heightened sense of awareness is fully evident in many of the interviews in this series. It makes the interviews credible, and it makes this series immensely valuable. I’m very pleased to be contributing to it.

Introduction

You will notice that Walt’s People: Volume 2 is quite a bit thicker than Volume 1. This is no coincidence. We are always expanding the fields we explore while trying to follow Walt’s idea of “giving you more than you would ever expect.”

To begin with, for the first time Walt’s People focuses on some of the artists who gave life to Disney comics. While Floyd Gottfredson and Carl Barks are the two names that come automatically to mind when Disney comics are mentioned, many other artists were involved in the creation of those gags and stories. Most of them are better known in Europe than in the United States. It is time to get their points of view. While Walt may not have been much involved in that field, comics nonetheless shaped the way Disney was and is perceived by entire generations all around the world. In this volume, Floyd Gottfredson gives us a first glimpse at this creative “planet”. This will be explored in more depth in future volumes, through the eyes of Tony Strobl, Jack Bradbury, Paul Murry, Don Rosa, and many others.

Walt’s People: Volume 2 also introduces the notion that, while the series focuses mainly on Disney artists’ careers within the Disney studio, it does not shy away from following them to other studios when the stories they have to tell justify it. This introduces a sense of perspective that only strengthens their “Disney” testimonies. Friz Freleng’s, Frank Tashlin’s, and Grim Natwick’s interviews in this volume are cases in point.

Finally, including an interview with Glen Keane allows us to clarify the subtitle of this book: “The Artists Who Knew Walt” are both the first and second generations of Walt’s artists. By that we mean artists who worked directly with Walt, like Eric Larson or Woolie Reitherman, and the artists they trained and therefore were exposed to Walt’s spirit, in this instance Richard Rich and Glen Keane. We felt it was important to introduce this new perspective, which in itself will never be the main focus of the series, but helps understand the full impact of the creative “chain reaction” that Walt started.

All these considerations aside, Volume 2 is thicker for a much simpler reason: it features many more interviews than Volume 1. And quite a few of them, like Woolie Reitherman’s, Eric Larson’s, and Dale Oliver’s are published in English for the first time. This symbolizes our commitment to providing never-seen-before, in-depth testimonies, with the hope that, volume after volume, anecdote after anecdote, the big picture will eventually emerge, at times surprising, but as Mike Barrier implied in his foreword, always exciting.

Don’t believe me? Then let’s step back in time…

Didier Ghez

Didier Ghez has conducted Disney research since he was a teenager in the mid-1980s. His articles about the Disney parks, Disney animation, and vintage international Disneyana, as well as his many interviews with Disney artists, have appeared in Animation Journal, Animation Magazine, Disney Twenty-Three, Persistence of Vision, StoryboarD, and Tomart’s Disneyana Update. He is the co-author of Disneyland Paris: From Sketch to Reality, runs the Disney History blog, the Disney Books Network, and serves as managing editor of the Walt’s People book series.

A Chat with Didier Ghez

If you have a question for Didier that you would like to see answered here, please get in touch and let us know what's on your mind.

About The Walt's People Series

How did you get the idea for the Walt's People series?

GHEZ: The Walt’s People project was born out of an email conversation I conducted with Disney historian Jim Korkis in 2004. The Disney history magazine Persistence of Vision had not been published for years, The “E” Ticket magazine’s future was uncertain, and, of course, the grandfather of them all, Funnyworld, had passed away 20 years ago. As a result, access to serious Disney history was becoming harder that it had ever been.

The most frustrating part of this situation was that both Jim and I knew huge amounts of amazing material was sleeping in the cabinets of serious Disney historians, unavailable to others because no one would publish it. Some would surface from time to time in a book released by Disney Editions, some in a fanzine or on a website, but this seemed to happen less and less often. And what did surface was only the tip of the iceberg: Paul F. Anderson alone conducted more than 250 interviews over the years with Disney artists, most of whom are no longer with us today.

Jim had conceived the idea of a book originally called Talking Disney that would collect his best interviews with Disney artists. He suggested this to several publishers, but they all turned him down. They thought the potential market too small.

Jim’s idea, however, awakened long forgotten dreams, dreams that I had of becoming a publisher of Disney history books. By doing some research on the web I realized that new "print-on-demand" technology now allowed these dreams to become reality. This is how the project started.

Twelve volumes of Walt's People later, I decided to switch from print-on-demand to an established publisher, Theme Park Press, and am happy to say that Theme Park Press will soon re-release the earlier volumes, removing the few typos that they contain and improving the overall layout of the series.

How do you locate and acquire the interviews and articles?

To locate them, I usually check carefully the footnotes as well as the acknowledgments in other Disney history books, then get in touch with their authors. Also, I stay in touch with a network of Disney historians and researchers, and so I become aware of newly found documents, such as lost autobiographies, correspondence with Disney artists, and so forth, as soon as they've been discovered.

Were any of them difficult to obtain? Anecdotes about the process?

Yes, some interviews and autobiographical documents are extremely difficult to obtain. Many are only available on tapes and have to be transcribed (thanks to a network of volunteers without whom Walt’s People would not exist), which is a long and painstaking process. Some, like the seminal interview with Disney comic artist Paul Murry, took me years to obtain because even person who had originally conducted the interview could not find the tapes. But I am patient and persistent, and if there is a way to get the interview, I will try to get it, even if it takes years to do so.

One funny anecdote involves the autobiography of the Head of Disney’s Character Merchandising from the '40s to the '70s, O.B. Johnston. Nobody knew that his autobiography existed until I found a reference to an article Johnston had written for a Japanese magazine. The article was in Japanese. I managed to get a copy (which I could not read, of course) but by following the thread, I realized that it was an extract from Johnston’s autobiography, which had been written in English and was preserved by UCLA as part of the Walter Lantz Collection. (Later in his career Johnston had worked with Woody Woodpecker’s creator.) Unfortunately, UCLA did not allow anyone to make copies of the manuscript. By posting a note on the Disney History blog a few weeks later, I was lucky enough to be contacted by a friend of Johnston's family, who lives in England and who had a copy of the manuscript. This document will be included in a book, Roy's People, that will focus on the people who worked for Walt's brother Roy.

How many more volumes do you foresee?

That is a tough question. The more volumes I release, the more I find outstanding interviews that should be made public, not to mention the interviews that I and a few others continue to conduct on an ongoing basis. I will need at least another 15 to 17 volumes to get most of the interviews in print.

About Disney's Grand Tour

You say that you've worked on this book for 25 years. Why so long?

DIDIER: The research took me close to 25 years. The actual writing took two-and-a-half years.

The official history of Disney in Europe seemed to start after World War II. We all knew about the various Disney magazines which existed in the Old World in the '30s, and we knew about the highly-prized, pre-World War II collectibles. That was about it. The rest of the story was not even sketchy: it remained a complete mystery. For a Disney historian born and raised in Paris this was highly unsatisfactory. I wanted to understand much more: How did it all start? Who were the men and women who helped establish and grow Disney's presence in Europe? How many were they? Were there any talented artists among them? And so forth.

I managed to chip away at the brick wall, by learning about the existence of Disney's first representative in Europe, William Banks Levy; by learning the name George Kamen; and by piecing together the story of some of the early Disney licensees. This was still highly unsatisfactory. We had never seen a photo of Bill Levy, there was little that we knew about George Kamen's career, and the overall picture simply was not there.

Then, in July 2011, Diane Disney Miller, Walt Disney's daughter, asked me a seemingly simple question: "Do you know if any photos were taken during the 'League of Nations' event that my father attended during his trip to Paris in 1935?" And the solution to the great Disney European mystery started to unravel. This "simple" question from Diane proved to be anything but. It also allowed me to focus on an event, Walt's visit to Europe in 1935, which gave me the key to the mysteries I had been investigating for twenty-three years. Remarkably, in just two years most of the answers were found.

Will Disney's Grand Tour interest casual Disney fans?

DIDIER: Yes, I believe that casual readers, not just Disney historians, will find it a fun read. The book is heavily illustrated. We travel with Walt and his family. We see what they see and enjoy what they enjoy. And the book is full of quotes from the people who were there: Roy and Edna Disney, of course, but also many of the celebrities and interesting individuals that the Disneys met during the trip. And on top of all of this, there is the historical detective work, that I believe is quite fun: the mysteries explored in the book unravel step by step, and it is often like reading a historical novel mixed with a detective story, although the book is strict non-fiction.

Walt bought hundreds of books in Europe and had them shipped back to the studio library. Were they of any practical use?

DIDIER: Those books provided massive new sources of inspiration to the Story Department. "Some of those little books which I brought back with me from Europe," Walt remarked in a memo dated December 23, 1935, "have very fascinating illustrations of little peoples, bees, and small insects who live in mushrooms, pumpkins, etc. This quaint atmosphere fascinates me."

What other little-known events in Walt's life are ripe for analysis?

DIDIER: There are still a million events in Walt's life and career which need to be explored in detail. To name a few:

- Disney during WWII (Disney historian Paul F. Anderson is working on this)

- Disney and Space (I am hoping to tackle that project very soon)

- The 1941 Disney studio strike

- Walt's later trips to Europe

The list goes on almost forever.

Other Books by Didier Ghez:

- They Drew as They Pleased: The Hidden Art of Disney's Golden Age (2015)

- Disney's Grand Tour: Walt and Roy's European Vacation, Summer 1935 (2013)

- Disneyland Paris: From Sketch to Reality (2002)

Didier Ghez has edited:

- Walt's People: Volume 15 (2014)

- Walt's People: Volume 14 (2014)

- Walt's People: Volume 13 (2013)

- Walt's People: Volume 12 (20xx)

- Walt's People: Volume 11 (20xx)

- Walt's People: Volume 10 (20xx)

- Walt's People: Volume 9 (20xx)

- Walt's People: Volume 8 (20xx)

- Walt's People: Volume 7 (20xx)

- Walt's People: Volume 6 (20xx)

- Walt's People: Volume 5 (20xx)

- Walt's People: Volume 4 (20xx)

- Walt's People: Volume 3 (2015)

- Walt's People: Volume 2 (2015)

- Walt's People: Volume 1 (2014)

- Life in the Mouse House: Memoir of a Disney Story Artist (2014)

- Inside the Whimsy Works: My Life with Walt Disney Productions (2014)

Ward Kimball talks about alcohol abuse at the early Disney studio, and indulges in a bit of psycho-analysis to explain Walt's antipathy toward cats.

JIM KORKIS: It seems to me that the biggest problem for the early Disney animators was not drug abuse but alcohol abuse like Fred Moore’s.

WARD KIMBALL: He’d start drinking around noon and by two o’clock he was fairly drunk and would swagger into a room asking, “Who would like a punch in the nose?” He also had the habit of taking off his coat and tossing it onto a coat rack. One day, I stole a saw and sawed the coat rack in three places and put it back together with transparent tape. The next time he tossed his coat, the entire pole fell apart. Somebody complained that he was getting so drunk he couldn’t finish his animation on The Reluctant Dragon, so I’d come back in the evenings and finish up some scenes for him.

JK: Didn’t one of Walt’s brothers have a little drinking problem?

WK: You’re probably thinking of Ray. He drank fairly heavily, but I still bought insurance from him. He was an insurance salesman. Ray would visit the studio and the Story Department wouldn’t let him come in with his big cigar. So he would leave it on a window sill. While he was inside, one of the story guys would snip the cigar in half or down to a little stub. Ray would come out and be puzzled about what happened to his cigar. This happened all the time and he never seemed to catch wise.

One day, I went over to get a copy of my insurance policy and he wouldn’t let me into his apartment. I had to plead that I had an appointment and just wanted a copy of my policy. He finally opened the door and it was pitch black inside. Once my eyes adjusted to the darkness, I saw that all around the place were those horseshoe flower wreaths that people put on graves. Apparently, he thought they were pretty and was going up to Forest Lawn and stealing them to use as decorations. On one wall was a bulletin board with yellowed newspaper clippings saying: “Walt Disney does this...” and “Walt Disney announces that...,” etc. But I got the feeling they were there not because he was proud of his brother but jealous of Walt.

JK: Animators often put themselves in their work. Which character that you worked on do you feel most resembles you?

WK: Lucifer the cat from Cinderella.

JK: You think you’re like an evil cat?

WK: You know, Walt Disney hated cats because they wouldn’t do what he told them. Walt needed to dominate. Maybe that’s why he always put up a wall between himself and others. Walt never really liked cats—anything in the cat family. Dogs you could train and tell ’em exactly what to do. Walt didn’t like cats because you could never control them. Somebody once said that all the despots of history—Napoleon, Henry VIII, Disney—never liked cats because they wouldn’t conform to their wishes. He really didn’t like interviews for the same reason. I suppose he was a little afraid or something that he might say the wrong thing. Walt wanted to be in control of the situation.

JK: So like a cat, you wouldn’t always do what Walt wanted?

WK: Walt was stubborn. Once he got something in his head that was it. I remember one time when he got really mad at me. I was working on the script for Babes in Toyland because if the picture was not put into production soon, the studio would lose the rights to do the story. So while Walt was over in Europe, somebody in the Publicity Department, to guarantee that the other studios knew Disney was doing the film, put a full-page ad in the trades that read, “Congratulations to Ward Kimball as he starts direction on Disney’s Babes in Toyland.” Well, Walt had wanted me to direct, but when he got back from Europe and saw the notice he thought I was pushing myself. So he removed me from the picture. I went in and pointed out that it was the Publicity Department that had done it and I even named the names of the guys involved. But Walt was stubborn and that was it.

JK: It seems to me you weren’t always the innocent party. I think you probably stirred up Walt occasionally on purpose.

WK: Walt would often call me up in the middle of the night with an idea or something to discuss and he’d always say, “Ward, this is Walt.” And I would always respond, “Walt WHO?” Then he’d get upset and yell, “Walt DISNEY for chrissake!” I told him, “Well, I know a lot of Walts.”

JK: I am still just amazed that Lucifer the cat is such a favorite of yours.

WK: I didn’t like the Cricket. That’s a fact. On the model sheet, I drew all these heads looking in every direction. We had these little figurines that they do out of Plaster of Paris and paint them. I have nine of those. The Cricket standing there in different poses. You can turn them around and see the 3D.

I like Lucifer the cat and the mice I did in Cinderella. Here’s a remarkable thing: I collect a lot of old antique toys and there never seemed to be many good images made of the Cinderella characters. All of a sudden, in a toy magazine, I saw a handcar with Gus-Gus, the little fat mouse, and Jaq with this handcar, like the old Lionel thing with Mickey and Minnie. I couldn’t believe it. I sent for it. It was in mint condition. They even had a pose of Lucifer on the side stalking these guys who were pumping. I had a lot of fun with Lucifer and the mice. It makes me smile even today.

Continued in "Walt's People: Volume 2"!

Glen Keane talk about "The Wild Things".

DIDIER GHEZ: There is one project that always intrigued me, which is the one you started with John Lasseter, called The Wild Things. Can you tell me more about that project?

GLEN KEANE: John and I had just seen the film Tron (1982). We were working on Mickey’s Christmas Carol at the time. John had just become an animator there. We both came back from the theatre right across the street really questioning what we were doing with animation. I remember coming back to my office and being kind of depressed. I felt like they were doing what was really exciting and we were doing dumb, flat drawings. There the computer was moving in three dimensions, you could go in the world, it was all so real and motorcycles were moving around and it was just...wow! It was eye candy!

John and I talked the same way. We were saying, “I just wish we could do something where the background was giving us the opportunity to bring the cartoon character into that world. That would really be cool.” So we started thinking about an idea for doing that.

John had read this story, The Brave Little Toaster. He showed me this book and he said, “Wouldn’t this be a great project to do for an animated film using nothing but the computer?” I said, “Wow! This is really cool! Maybe we can do the backgrounds and then we can animate the characters and solid kinds of shapes…”

We figured we had better do a test first and we came up with this idea of Where the Wild Things Are. We both liked that story by Maurice Sendak.

We did a little test where the kid Max is drawing his name on the wall and the dog is watching him. Actually, the dog is under the bed, and when Max finishes drawing on the wall, the camera follows him as he looks under the bed at this little dog upside down.

The dog raises toward the camera, looking at you. The camera lifts up as the dog runs down the hall and he runs after the dog. There is this chase of the little boy and the dog down this staircase. We were just willing to try and explore how we would do all this and to try and color it, to try and put shading, so that it would look like these characters were fitting into this world. Nobody had ever done that before. That was the first time computer backgrounds had been combined with animation.

And we went to that company in New York which had worked on Tron and it worked. It was just a nice little short piece, a wonderful film.

(According to Charles Solomon, in The History of Animation: Lasseter constructed a model of Max’s bedroom and the adjoining hall in the computer’s memory. After the artists calculated the rates of movements for Max and his dog, the computer produced simple models, showing where the characters would be in each frame. Keane animated the characters, using the computer printouts as guides. When his drawings were entered into the computer and colored, the characters were placed in the computer-generated environment.

In the resulting footage, the camera seemed to follow Max as he chased the hapless dog around the bedroom and through the hall, jumped over the banister, and pursued his pet down the stairs. Keane’s animation captured the personalities of the characters and made them seem alive. The computer made it possible to use the complex tracking shot, which would be virtually impossible to do in conventional animation, as it would be too difficult to draw everything in perspective. This experiment helped lead to the use of a computer-generated environment for the climax of The Great Mouse Detective.)

After that, we started to develop The Brave Little Toaster and John really went on to work much more in depth on that and I started to work on The Great Mouse Detective. That was the first time when we actually brought the computer into our film, at the end in the big chase up in Big Ben.

John, meanwhile, went on and left Disney. By that point, his interests went completely into computers and he ran off in that direction. Disney at that time was also really struggling financially and Brave Little Toaster became a project that was sacrificed. There were a lot of political problems at the time. I am not going to go into all of that.

So John left to develop computer animation and I kept focusing more and more on hand-drawn animation. I guess it was at a time when I had explored enough with the computer to know where my heart was. It was in drawing. I loved the feel of the graphite on the paper.

For John, drawing was always a frustrating thing. It was a necessary evil. For me, it’s the greatest joy. Animation is never as good as when I am sitting at that desk drawing. That’s the best. Even when it’s up on the screen, it’s never as wonderful as the moments when it was drawn.

DG: How was The Wild Things received by the studio?

GK: We showed it to the studio executives and everybody and they were all very excited. They thought it was really cool and interesting. But animation was at such a point there, and there was not much foresight in management at the time to see how to implement it at Disney.

Today, with a whole different spirit in animation here, a test of that magnitude and a discovery like that would just be eaten up and incorporated into a film. In those days, it took a lot longer. Still, it was the beginning. The clockwork stuff was beginning to develop in The Great Mouse Detective and on from there. It planted the seed. It just took a while to get it going.

Continued in "Walt's People: Volume 2"!

About Theme Park Press

Theme Park Press is the world's leading independent publisher of books about the Disney company, its history, its films and animation, and its theme parks. We make the happiest books on earth!

Our catalog includes guidebooks, memoirs, fiction, popular history, scholarly works, family favorites, and many other titles written by Disney Legends, Disney animators and artists, Mouseketeers, Cast Members, historians, academics, executives, prominent bloggers, and talented first-time authors.

We love chatting about what we do: drop us a line, any time.

Theme Park Press Books

The Unauthorized Story of Walt Disney's Haunted Mansion The Ride Delegate 501 Ways to Make the Most of Your Walt Disney World Vacation The Cotton Candy Road Trip The Wonderful World of Customer Service at Disney Disney Destinies Disney Melodies The Happiest Workplace on Earth Storm over the Bay A Historical Tour of Walt Disney World: Volume 1 Mouse in Transition Mouseketeers Down Under Murder in the Magic Kingdom Walt Disney and the Promise of Progress City Service with Character Son of Faster Cheaper A Tale of Two Resorts I Saw Ariel Do a Keg Stand The Adventures of Young Walt Disney Death in the Tragic Kingdom Two Girls and a Mouse Tale Ears & Bubbles The Easy Guide 2015 Who's the Leader of the Club? Disney's Hollywood Studios Funny Animals Life in the Mouse House The Book of Mouse Disney's Grand Tour The Accidental Mouseketeer The Vault of Walt: Volume 1 The Vault of Walt: Volume 2 The Vault of Walt: Volume 3 Who's Afraid of the Song of the South? Amber Earns Her Ears Ema Earns Her Ears Sara Earns Her Ears Katie Earns Her Ears Brittany Earns Her Ears Walt's People: Volume 1 Walt's People: Volume 2 Walt's People: Volume 13 Walt's People: Volume 14 Walt's People: Volume 15

Write for Theme Park Press

We're always in the market for new authors with great ideas. Or great authors with new ideas. Whichever type of author you are, we'd be happy to discuss your book. Before you contact us, however, please make sure you can answer "yes" to these threshold questions:

Is It Right for Us?

We specialize in books that have some connection to Disney or theme parks. Disney, of course, has become a broad topic, and encompasses not just theme parks and films but comic books, animation, and a big chunk of pop culture. Your book should fit into one (or more) of those broad categories.

Is It Going to Make Money?

There's never a guarantee that any book will make money, but certain types of books are less likely to do so than others. They include: hardcovers, books with color photos, and books that go on forever ("forever" as in 400+ pages). We won't automatically turn down these types of books, but you'll have to be a really good salesman to convince us.

Are You Great to Work With?

Writing books and publishing books should be fun. The last thing you want, and the last thing we want, is a contentious relationship. We work with authors who share our philosophy of no drama and zero attitude, and the desire for a respectful, realistic, mutually beneficial partnership.

If you said "yes" three times, please step inside.