- Visit the Imagineering Graveyard

- Now Sailing: "Skipper Stories" - Tales from the Jungle Cruise

- Coming Soon: The biography of Disney animator Jack Hannah

- Coming Soon: A Haunted Mansion anthology

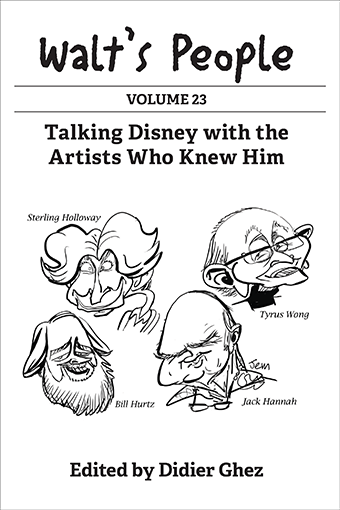

Walt's People: Volume 23

Talking Disney with the Artists Who Knew Him

by Didier Ghez | Release Date: December 1, 2019 | Availability: Print, Kindle

Disney History from the Source

The Walt's People series is an oral history of all things Disney, as told by the artists, animators, designers, engineers, and executives who made it happen, from the 1920s through the present. In this volume: Woolie Reitherman, Jack Hannah, Joe Potter, Sterling Holloway, and many more.

Walt's People: Volume 23 features appearances by Peter Adby, Sterling Holloway, Tyrus Wong, Woolie Reitherman, Les Novros, Bill Hurtz, Paul Julian, Rudy Cataldi, Bob Harpur, Jack Hannah, Joe Potter, and Jeff Burke.

Among the hundreds of stories in this volume:

- WOOLIE REITHERMAN explains the process of animation at the Disney studio, as well as the genesis of such films as Robin Hood and The Rescuers.

- STERLING HOLLOWAY talks about his early years in show business as an actor, and how he met Walt Disney who cast him memorably as a voice actor in The Jungle Book.

- JOE POTTER reflects upon his long career in the military and his instrumental role in planning and building Walt Disney World, both before and after Walt's death.

- JEFF BURKE provides a book-length commentary about his many years as a Disney Imagineer working on theme park attractions at Walt Disney World and Epcot, and Disneyland Paris.

The entertaining, informative stories in every volume of Walt's People will please both Disney scholars and eager fans alike.

Table of Contents

Foreword

Introduction

Peter Adby

Sterling Holloway: A Way with Words

Sterling Holloway

Tyrus Wong

Woolie Reitherman and Ken Anderson

Woolie Reitherman

Les Novros, Bill Hurtz, and Paul Julian

Rudy Cataldi

Bob Harpur

Jack Hannah

Joe Potter

Jeff Burke

Further Reading

Foreword

Since the creation of the art of animation at the beginning of the 20th century, there has been the problem of how to pass on to future generations the accumulated knowledge gathered about the medium. Like all new technologies, it took almost a generation for people to begin trying to preserve their past. Hollywood studios treated old short cartoons and their artwork like they were old newspapers. James Stuart Blackton, the first American animator, did not even bother to mention in his memoirs that he was the first animator. It is not just about the mechanical lessons of how to animate, but the knowledge of the shared experiences of animation artists in their time. The way Samuel Pepys’ memoirs of Restoration England of the 1660s were considered inconsequential in their day, and are now considered an essential resource to understanding their time.

People have written how-to books since Edwin Lutz’s Animated Cartoons, How They Are Made (1920), that young Walt Disney found so useful. Preston Blair’s 1953 workbook, Halas & Batchelor’s Techniques in Film Animation, and Frank Tomas and Ollie Johnston’s Disney Animation—The Illusion of Life, became standard texts. There have been many great schools teaching animation over the years: Chouinard, CalArts, The University of Southern California, UCLA, Sheridan, The School of Visual Arts, NYU, The Savannah College of Design, The Ringling School, The Ecole des Gobelins, The Filmakademie of Baden-Wurtemberg, and more. Add to that all the online courses and software tutorials and it becomes a pretty substantial amount of scholarship.

Yet for most of the animators of my generation, nothing compared to being able to learn about your craft at the edge of the desk of some great animator of the past. For many years, the best way to learn the art of animation was master-to-apprentice.

I was fortunate enough that when I began my animation career in the 1970s, many of the artists of the Golden Age of Hollywood Animation were just beginning to retire. I was able to hear from their own lips what they experienced, and their impressions of great people like Walt Disney and Mary Blair. The animators of my generation were taught to venerate these master craftsmen. The elders themselves were often eager to pass on what they knew to ensure their knowledge would live on and not fade into obscurity.

Many of the Walt Disney animators of the Second Golden Age (Silver Age, Renaissance of the ’90s, whatever) were tutored by masters like Eric Larson, Marc Davis, Elmer Plummer, Kendall O’Connor, Jack Hannah, and T. Hee. After an official period of training, they would go on to work under master animators like Frank Thomas and Ollie Johnston. Glen Keane often spoke of maxims he learned from Ollie, like, “Don’t move a character until they want to.” Andreas Deja spoke about everything he learned from Milt Kahl. Nancy Beiman learned a great deal from Kendall O’Connor. For those of us who began our careers outside of the Mouse House, Richard Williams was known for bringing in past masters like Art Babbitt and Ken Harris to teach us. Maurice Noble took so many young artists under his wing that they were collectively known as The Noble Boys. These included future Disney animator-directors like Rob Minkoff, Kelly Asbury, Michael Giaimo, Sue Goldberg, and Chris Bailey.

I myself was fortunate to learn my craft under Shamus Culhane, Art Babbitt, Grim Natwick, and Chuck Jones animator Ben Washam. What they taught me was exponentially way more advanced than what I had learned in my college-level animation courses. Everything from timing tips and calculating compensating pans to twisting a rubber band across your pegs to hold your pages down while drawing. That last tip I got from Helen Komar, who was once an assistant to Bill Tytla in New York.

As much as they taught us by telling us their maxims, we also learned from their experiences, their challenges, like Samuel Pepys, in their day-to-day occurrences. What they did to get to be as good as they were. Which of their outside experiences influenced how they animated. Marc Davis told me Grim Natwick taught him not only how to animate, but how to enjoy good wine and fine cuisine. Bill Tytla trained at the Art Students League in N.Y., as I did. Dave Hilberman traveled to Leningrad and studied avant-garde theater arts under Mayakovsky. Before Walt brought in Don Graham to lecture, Art Babbitt and the other artists hired models and held informal life-drawing classes in their house to improve their skills. They taught us by example as much as by lecture.

Most of those voices are silent now, as it is in the Circle of Life. We the living are left hoping we collected a complete enough record of what they said. That is why it is so important to record and publish verbatim their thoughts and recollections: that future generations may benefit. That was their final wish. Today when I teach students, I do it not just to make a living, but I am paying back my debt to Babbitt and Culhane for their confidence in me.

That is why I am so grateful to Didier Ghez and his team of archivists for continuing this series of books. Didier’s search for first-person accounts of life at the Walt Disney Studio helps preserve these precious nuggets of information for future scholars. Recording the thoughts of some Disney employees who otherwise might never see the light of day. Things that may seem trivial to some, to others may open a door to a new revelation. So read on, and enjoy.

Introduction

There is still so much to learn about Disney history. The Hyperion Historical Alliance (HHA), a non-profit association that I have the honor of leading, just released the 2019 Hyperion Historical Alliance Annual a few days ago and each and every article it contains was a revelation to me, opening new doors and bringing to the fore hidden documents and knowledge. This is also true, of course, of the two upcoming monographs from the HHA: The Making of Walt Disney’s Fun and Fancy Free by J.B. Kaufman and Disneyland 1959 by Todd James Pierce and Joe Campana.

What I find especially stunning is the number of historical gaps that remain to be bridged. I was writing an essay a few days ago about one of Disney’s first female story artists, Grace Huntington, and the amount of new information I was able to dig up surprised me. But what really bewildered me is that, by researching that specific subject, I was able to make a number of significant discoveries related to the proposed Mickey features in the 1930s. Yes, “features,” plural, you read properly. I was also recently conducting some research about the origins of Disney’s “Publicity Production Department,” the internal art department headed at different points in time by artists Mique Nelson, Tom Wood, and Hank Porter, and there again I realized that not much had been written about that specific subject and that lots remained to be discovered. Then there is the history of “True-Life Adventures,” which is absorbing a lot of my time right now. And again, I am finding out that most of what we know or thought we knew is based on myth and publicity stories created by the Disney studio. The real story is more complex and more exciting that anything we knew.

None of these discoveries would happen, however, without three important factors: New historical documents being discovered (the correspondence and diary of Grace Huntington, the papers of Al and Elma Milotte, etc.), enhanced collaboration between Disney scholars, and new venues to release the fruits of our research.

Among the nicest documents that I unearthed in recent months is the excellent article by Joe Collura about Sterling Holloway. When I started researching Holloway, I realized that surprisingly little had been written about him, hence my excitement when I located this article and when Joe allowed me to include it in this volume of Walt’s People. It was thanks to enhanced collaboration between Disney scholars, and especially thanks to the probing of my friend Julie Svendsen, that I was able to conduct the in-depth interview with Imagineer Jeff Burke which concludes this volume. As to the piece which opens this volume, the correspondence with British artist Peter Adby, it would not exist if it weren’t for the efforts of Bob McLain and of my good friend and fellow Disney historian, Libby Spatz.

I hope you will enjoy the fruits of our collaboration and all those new discoveries!

Didier Ghez

Didier Ghez has conducted Disney research since he was a teenager in the mid-1980s. His articles about the Disney parks, Disney animation, and vintage international Disneyana, as well as his many interviews with Disney artists, have appeared in Animation Journal, Animation Magazine, Disney Twenty-Three, Persistence of Vision, StoryboarD, and Tomart’s Disneyana Update. He is the co-author of Disneyland Paris: From Sketch to Reality, runs the Disney History blog, the Disney Books Network, and serves as managing editor of the Walt’s People book series.

A Chat with Didier Ghez

If you have a question for Didier that you would like to see answered here, please get in touch and let us know what's on your mind.

About The Walt's People Series

How did you get the idea for the Walt's People series?

GHEZ: The Walt’s People project was born out of an email conversation I conducted with Disney historian Jim Korkis in 2004. The Disney history magazine Persistence of Vision had not been published for years, The “E” Ticket magazine’s future was uncertain, and, of course, the grandfather of them all, Funnyworld, had passed away 20 years ago. As a result, access to serious Disney history was becoming harder that it had ever been.

The most frustrating part of this situation was that both Jim and I knew huge amounts of amazing material was sleeping in the cabinets of serious Disney historians, unavailable to others because no one would publish it. Some would surface from time to time in a book released by Disney Editions, some in a fanzine or on a website, but this seemed to happen less and less often. And what did surface was only the tip of the iceberg: Paul F. Anderson alone conducted more than 250 interviews over the years with Disney artists, most of whom are no longer with us today.

Jim had conceived the idea of a book originally called Talking Disney that would collect his best interviews with Disney artists. He suggested this to several publishers, but they all turned him down. They thought the potential market too small.

Jim’s idea, however, awakened long forgotten dreams, dreams that I had of becoming a publisher of Disney history books. By doing some research on the web I realized that new "print-on-demand" technology now allowed these dreams to become reality. This is how the project started.

Twelve volumes of Walt's People later, I decided to switch from print-on-demand to an established publisher, Theme Park Press, and am happy to say that Theme Park Press will soon re-release the earlier volumes, removing the few typos that they contain and improving the overall layout of the series.

How do you locate and acquire the interviews and articles?

To locate them, I usually check carefully the footnotes as well as the acknowledgments in other Disney history books, then get in touch with their authors. Also, I stay in touch with a network of Disney historians and researchers, and so I become aware of newly found documents, such as lost autobiographies, correspondence with Disney artists, and so forth, as soon as they've been discovered.

Were any of them difficult to obtain? Anecdotes about the process?

Yes, some interviews and autobiographical documents are extremely difficult to obtain. Many are only available on tapes and have to be transcribed (thanks to a network of volunteers without whom Walt’s People would not exist), which is a long and painstaking process. Some, like the seminal interview with Disney comic artist Paul Murry, took me years to obtain because even person who had originally conducted the interview could not find the tapes. But I am patient and persistent, and if there is a way to get the interview, I will try to get it, even if it takes years to do so.

One funny anecdote involves the autobiography of the Head of Disney’s Character Merchandising from the '40s to the '70s, O.B. Johnston. Nobody knew that his autobiography existed until I found a reference to an article Johnston had written for a Japanese magazine. The article was in Japanese. I managed to get a copy (which I could not read, of course) but by following the thread, I realized that it was an extract from Johnston’s autobiography, which had been written in English and was preserved by UCLA as part of the Walter Lantz Collection. (Later in his career Johnston had worked with Woody Woodpecker’s creator.) Unfortunately, UCLA did not allow anyone to make copies of the manuscript. By posting a note on the Disney History blog a few weeks later, I was lucky enough to be contacted by a friend of Johnston's family, who lives in England and who had a copy of the manuscript. This document will be included in a book, Roy's People, that will focus on the people who worked for Walt's brother Roy.

How many more volumes do you foresee?

That is a tough question. The more volumes I release, the more I find outstanding interviews that should be made public, not to mention the interviews that I and a few others continue to conduct on an ongoing basis. I will need at least another 15 to 17 volumes to get most of the interviews in print.

About Disney's Grand Tour

You say that you've worked on this book for 25 years. Why so long?

DIDIER: The research took me close to 25 years. The actual writing took two-and-a-half years.

The official history of Disney in Europe seemed to start after World War II. We all knew about the various Disney magazines which existed in the Old World in the '30s, and we knew about the highly-prized, pre-World War II collectibles. That was about it. The rest of the story was not even sketchy: it remained a complete mystery. For a Disney historian born and raised in Paris this was highly unsatisfactory. I wanted to understand much more: How did it all start? Who were the men and women who helped establish and grow Disney's presence in Europe? How many were they? Were there any talented artists among them? And so forth.

I managed to chip away at the brick wall, by learning about the existence of Disney's first representative in Europe, William Banks Levy; by learning the name George Kamen; and by piecing together the story of some of the early Disney licensees. This was still highly unsatisfactory. We had never seen a photo of Bill Levy, there was little that we knew about George Kamen's career, and the overall picture simply was not there.

Then, in July 2011, Diane Disney Miller, Walt Disney's daughter, asked me a seemingly simple question: "Do you know if any photos were taken during the 'League of Nations' event that my father attended during his trip to Paris in 1935?" And the solution to the great Disney European mystery started to unravel. This "simple" question from Diane proved to be anything but. It also allowed me to focus on an event, Walt's visit to Europe in 1935, which gave me the key to the mysteries I had been investigating for twenty-three years. Remarkably, in just two years most of the answers were found.

Will Disney's Grand Tour interest casual Disney fans?

DIDIER: Yes, I believe that casual readers, not just Disney historians, will find it a fun read. The book is heavily illustrated. We travel with Walt and his family. We see what they see and enjoy what they enjoy. And the book is full of quotes from the people who were there: Roy and Edna Disney, of course, but also many of the celebrities and interesting individuals that the Disneys met during the trip. And on top of all of this, there is the historical detective work, that I believe is quite fun: the mysteries explored in the book unravel step by step, and it is often like reading a historical novel mixed with a detective story, although the book is strict non-fiction.

Walt bought hundreds of books in Europe and had them shipped back to the studio library. Were they of any practical use?

DIDIER: Those books provided massive new sources of inspiration to the Story Department. "Some of those little books which I brought back with me from Europe," Walt remarked in a memo dated December 23, 1935, "have very fascinating illustrations of little peoples, bees, and small insects who live in mushrooms, pumpkins, etc. This quaint atmosphere fascinates me."

What other little-known events in Walt's life are ripe for analysis?

DIDIER: There are still a million events in Walt's life and career which need to be explored in detail. To name a few:

- Disney during WWII (Disney historian Paul F. Anderson is working on this)

- Disney and Space (I am hoping to tackle that project very soon)

- The 1941 Disney studio strike

- Walt's later trips to Europe

The list goes on almost forever.

Other Books by Didier Ghez:

- They Drew as They Pleased: The Hidden Art of Disney's Golden Age (2015)

- Disney's Grand Tour: Walt and Roy's European Vacation, Summer 1935 (2013)

- Disneyland Paris: From Sketch to Reality (2002)

Didier Ghez has edited:

- Walt's People: Volume 15 (2014)

- Walt's People: Volume 14 (2014)

- Walt's People: Volume 13 (2013)

- Walt's People: Volume 12 (20xx)

- Walt's People: Volume 11 (20xx)

- Walt's People: Volume 10 (20xx)

- Walt's People: Volume 9 (20xx)

- Walt's People: Volume 8 (20xx)

- Walt's People: Volume 7 (20xx)

- Walt's People: Volume 6 (20xx)

- Walt's People: Volume 5 (20xx)

- Walt's People: Volume 4 (20xx)

- Walt's People: Volume 3 (2015)

- Walt's People: Volume 2 (2015)

- Walt's People: Volume 1 (2014)

- Life in the Mouse House: Memoir of a Disney Story Artist (2014)

- Inside the Whimsy Works: My Life with Walt Disney Productions (2014)

About Theme Park Press

Theme Park Press is the world's leading independent publisher of books about the Disney company, its history, its films and animation, and its theme parks. We make the happiest books on earth!

Our catalog includes guidebooks, memoirs, fiction, popular history, scholarly works, family favorites, and many other titles written by Disney Legends, Disney animators and artists, Mouseketeers, Cast Members, historians, academics, executives, prominent bloggers, and talented first-time authors.

We love chatting about what we do: drop us a line, any time.

Theme Park Press Books

The Unauthorized Story of Walt Disney's Haunted Mansion The Ride Delegate 501 Ways to Make the Most of Your Walt Disney World Vacation The Cotton Candy Road Trip The Wonderful World of Customer Service at Disney Disney Destinies Disney Melodies The Happiest Workplace on Earth Storm over the Bay A Historical Tour of Walt Disney World: Volume 1 Mouse in Transition Mouseketeers Down Under Murder in the Magic Kingdom Walt Disney and the Promise of Progress City Service with Character Son of Faster Cheaper A Tale of Two Resorts I Saw Ariel Do a Keg Stand The Adventures of Young Walt Disney Death in the Tragic Kingdom Two Girls and a Mouse Tale Ears & Bubbles The Easy Guide 2015 Who's the Leader of the Club? Disney's Hollywood Studios Funny Animals Life in the Mouse House The Book of Mouse Disney's Grand Tour The Accidental Mouseketeer The Vault of Walt: Volume 1 The Vault of Walt: Volume 2 The Vault of Walt: Volume 3 Who's Afraid of the Song of the South? Amber Earns Her Ears Ema Earns Her Ears Sara Earns Her Ears Katie Earns Her Ears Brittany Earns Her Ears Walt's People: Volume 1 Walt's People: Volume 2 Walt's People: Volume 13 Walt's People: Volume 14 Walt's People: Volume 15

Write for Theme Park Press

We're always in the market for new authors with great ideas. Or great authors with new ideas. Whichever type of author you are, we'd be happy to discuss your book. Before you contact us, however, please make sure you can answer "yes" to these threshold questions:

Is It Right for Us?

We specialize in books that have some connection to Disney or theme parks. Disney, of course, has become a broad topic, and encompasses not just theme parks and films but comic books, animation, and a big chunk of pop culture. Your book should fit into one (or more) of those broad categories.

Is It Going to Make Money?

There's never a guarantee that any book will make money, but certain types of books are less likely to do so than others. They include: hardcovers, books with color photos, and books that go on forever ("forever" as in 400+ pages). We won't automatically turn down these types of books, but you'll have to be a really good salesman to convince us.

Are You Great to Work With?

Writing books and publishing books should be fun. The last thing you want, and the last thing we want, is a contentious relationship. We work with authors who share our philosophy of no drama and zero attitude, and the desire for a respectful, realistic, mutually beneficial partnership.

If you said "yes" three times, please step inside.