- Visit the Imagineering Graveyard

- Now Sailing: "Skipper Stories" - Tales from the Jungle Cruise

- Coming Soon: The biography of Disney animator Jack Hannah

- Coming Soon: A Haunted Mansion anthology

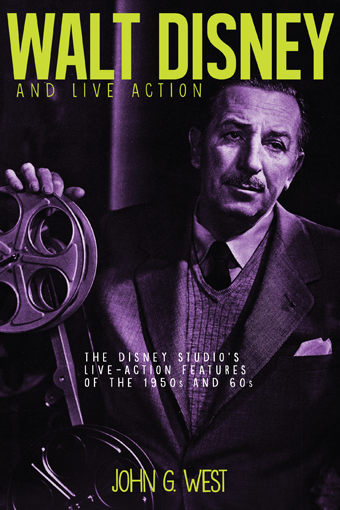

Walt Disney and Live Action

The Disney Studio's Live-Action Features of the 1950s and 60s

by Dr. John G. West | Release Date: October 16, 2016 | Availability: Print, Kindle

Beyond Animation

In this definitive guide to Walt Disney's live-action output, Dr. John G. West explores an often overlooked but important chapter in Disney cinematic history: the live-action films and television shows released by the Disney studio during Walt's lifetime.

From blockbuster movies like 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea, Mary Poppins, and Treasure Island, to such lesser-known efforts as Savage Sam and Monkeys, Go Home!, West describes the production of each film in detail, with backstage stories and complete cast and crew information.

The small screen output of the Disney studio is given similar treatment: over 70 episodes of Zorro, Texas John Slaughter, Davy Crockett, and other TV series are described and catalogued, along with in-depth analyses of the shows themselves.

Plus, the book features over 80 photos, many of them never seen before, including candid shots of Walt Disney in his office.

In addition to his detailed coverage of Disney's live-action films and TV shows, West devotes several chapters to a fast-moving but comprehensive history of the Disney studio's live-action productions, from the producers, directors, writers, composers, and set directors involved, to the meanings behind Walt's live-action films and the values he sought to impart on American culture.

Table of Contents

Introduction

Part One: The Man

Chapter 1: The Man Who Was a Studio

Chapter 2: The Man Behind the Myth

Chapter 3: Aesop in Hollywood

Part Two: The Meaning

Chapter 4: Fanfare for Common Men

Chapter 5: We Hold These Truths

Chapter 6: God and Duty

Chapter 7: Modern Times

Part Three: The Making

Chapter 8: Live-Action Production and the Disney Studio

Chapter 9: Filmography

Epilogue: The Years After Walt

Source Notes

Introduction

Walt Disney was “the man you loved to hate or hated to love,” wrote Ray Bradbury once. “He was the man…who could never win.”

At first, Bradbury’s observation might seem almost nonsensical. Who, after all, could hate Walt Disney? Among Baby Boomers and many Gen Xers, even the most cold-hearted of us as children reveled in the adventures of Mickey Mouse and the pranks of Donald Duck. Hayley Mills was our secret sweetheart; Fred MacMurray and Dorothy McGuire our surrogate parents; Disneyland our ultimate playground.

Once we became adults, many of us continued to be incurable Disneyholics. Walt Disney has been dead for nearly half a century, but one would be hard-pressed to prove that fact by measuring his presence in American popular culture in the decades since his death. His animated features invariably rose to the top of the sales charts when released on videotape. The Disney cable channel (fed initially by Disney live-action re-runs) succeeded at a time when many new cable ventures were going bankrupt. Attendance figures at Disneyland and Walt Disney World have continued to spiral upward.

Walt Disney’s presence can be felt today even in films that he never had a hand in making. Two of the most successful filmmakers since the 1970s—Steven Spielberg and George Lucas—both claim to walk in Disney’s footsteps. Spielberg goes so far as to claim that every time he makes a film, he asks himself “Would Walt Disney like this?” The perceptive movie watcher could have guessed as much: Spielberg has paid fleeting tributes to Disney in some of his most popular films (Close Encounters of the Third Kind and Back to the Future, to name two).

Yet in spite of the tremendous and continuing veneration; in spite of our perpetual adoration of Davy Crockett, Mary Poppins, and all things Disney; in spite of it all—Ray Bradbury was, I fear, right.

Americans are not known for being consistent, and the treatment accorded Walt Disney supplies a case in point. There is a kind of schizophrenia that seizes us when his name is mentioned. Beneath the adoration simmers condescension and—shall I dare say it?—contempt. Even during his own lifetime, of course, Disney faced some stringent attacks. He was debunked by everyone from baby-doctor Benjamin Spock (who attacked the “sadism” in Disney’s cartoons) to UCLA librarian Frances Sayers, who sourly noted: “In the Disney films, I find genuine feeling ignored, the imagination of children bludgeoned with mediocrity, and much of it overcast with vulgarity.”

After Disney’s untimely demise in 1966, both the attacks and the eulogies became more passionate. On the one hand, public figures scrambled to lavish praise on the now-dead patriarch of family entertainment. Two months after Disney’s death, actor Maurice Chevalier called Disney “almost kind of a smiling saint… I think he was just as pure as a man as he was as an artist. Almost everything he did I liked immensely because it was always gentle. It was funny. It was healthy. It was attractive. It had everything.”

Others disagreed. When a postage stamp in Disney’s honor was announced in 1968, the Christian Century magazine bristled with displeasure: “[T]hough children and teen-agers may not have been aware of the sex-dirt-politics Disney regularly fed them, they were being fed… Disney was anti-sexual… Disney introduced more pointless sadism and violence (sugar-coated, of course) into the American tradition than did Bonnie and Clyde.”

Most film critics, meanwhile, simply forgot that Disney had ever been born. And those who remembered did not necessarily do so out of admiration. Take Richard Schickel’s rationale for writing his scathing attack on Disney, The Disney Version (published initially in 1967 and reissued in paperback in 1985). Schickel, a film critic for Time magazine, said that people often asked him why he would devote almost two years of his life to the “study of a man whom few writers or critics have taken seriously for more than a quarter of a century.” Schickel’s pungent answer: “Our environment, our sensibilites, the very quality of both our waking and sleeping hours, are all formed largely by people with no more artistic conscience or intelligence than a kumquat. If the happy few do not study them at least as seriously as they study Andy Warhol, then they will lose their grip on the American reality and, with it, whatever chance they might have of remaking it in a more pleasing style.” Schickel might sound cruel, but his comment is more the rule than the exception when it comes to Walt Disney’s critics. Unsurprisingly, when Schickel’s book attacking Disney came out, it was soundly lauded in the New York Times Book Review, the Los Angeles Times, and Newsweek.

None of this is to suggest that Disney has had no able defenders. He has had several; but the praise they’ve bestowed has often been highly selective. We honor Disney most today for his stunning achievements in animation, his entrepreneurial genius, and his founding of that never-never-world known as Disneyland. Few lavish praise on the craftsmanship and content of his live-action productions. (Leonard Maltin continues to be a refreshing exception.) Even some of Disney’s most doting admirers seem willing to accept Richard Schickel’s grim assessment that the Disney live-action films “were all, one way or another, too cozy, too bland, too comfortable and comforting.”

This book is dedicated to the proposition that Schickel and those who agree with him are almost wholly wrong. Looking back at Disney’s live-action productions after all these years, one finds them surprisingly good. They feature brisk pacing, engaging casts, literate scripts, and a fairly brilliant use of visuals; few fall into the sweet and saccharine category that most seem to expect (most such films came after Disney died, not before).

Nor is the content of Disney live-action efforts nearly as trite and listless as some would have us believe. Many of his films provided commentary (albeit subtle commentary) on the social ills pervading post-war America. They taught pressing lessons about the nature of virtue and vice in the modern world. They steadfastly—and sometimes rather eloquently—upheld the democratic ideals upon which America is premised.

Walt Disney was neither a philosopher nor a classical dramatist, but he keenly understood that good ethics are an invariable part of good drama. “Good and evil” are “the antagonists of all great drama,” he once observed. They “must be believably personalized.” And in the ensuing conflict, “the moral ideas common to all humanity must be upheld.”

In his stories, they were.

From The Absent-Minded Professor to Zorro, Walt Disney instilled in his productions a consistent ethos with few parallels in the rest of Hollywood. This book is partly an exploration of that ethos and how it was expressed in countless Disney features.

But it is much else as well: It is part biography, part history, part filmography, part social criticism—and part rollicking tale of how the Disney live-action films and television features were actually made. The book is divided into four sections. Part One discusses Disney the man and chronicles how he ran the live-action end of his studio. Part Two explores the social and moral meaning of his live-action work. Part Three supplies extensive production histories for most of his live-action features, drawing on my original interviews with Disney directors, stars, producers, scriptwriters, art directors, and composers. Part Four contains an epilogue that tells the story of what happened to live-action production at the Disney studio after Walt Disney’s death.

I have fond memories of writing this book. Most of the research for it took place while I was a twenty-something graduate student living in southern California, pursuing my Ph.D. in Government. The most rewarding part of my research was meeting in person the people who brought Walt Disney’s live-action productions to life. I will always treasure their graciousness, their warmth, and their hospitality. They were living testaments to the type of virtues extolled in the Disney films. This book is intended to honor them as much as Walt Disney.

When Walt Disney and Live Action was originally published in 1994 (under a different title), it was the first book to deal solely with Walt Disney’s live-action output. The original edition has now been out of print for a number of years, and I am grateful to Bob McLain and Theme Park Press for making it available in a new edition. Although the new edition is substantially the same as the first one, I have taken the opportunity to correct previous errors, add or expand several production histories, and update various passages.

My one major regret about the original edition was that I was unable to reprint any photos from my extensive archive of Disney studio publicity photos, because I could not afford the licensing fees required by the Walt Disney Company. This time around, I made an astonishing discovery: I learned that the Library of Congress holds a trove of largely unpublished photos connected with various Walt Disney live-action productions. These photos were taken by staff photographers for Look magazine. When that magazine went out of business in the early 1970s, its owners gifted the photos (and the rights to them) to the American people. As a result of this stunning act of generosity, you will get to see photos taken during the production of classics such as Davy Crockett, 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea, Darby O’Gill and the Little People, Old Yeller, and Mary Poppins. You will also get to see candid photos of Walt Disney working at his studio in the 1950s as well as rare publicity photos taken of Hayley Mills during her time under contract with the Disney studio. To the best of my knowledge, many of these photos have never been previously published.

Whether you are a long-time fan of Walt Disney’s live-action productions, or someone who has just discovered them, I hope you will enjoy reading this book as much as I enjoyed writing it.

Dr. John G. West

John G. West is an author and documentary filmmaker who lives in the Pacific Northwest. His books and films include The Magician’s Twin, Darwin Day in America, The C.S. Lewis Readers’ Encyclopedia, The Politics of Revelation and Reason, Fire-Maker, Revolutionary, and Darwin’s Heretic. A former university professor, he currently serves as vice president of Discovery Institute and associate director of its Center for Science and Culture.

Walt's live-action films were meant for a modern audience, but the message in his movies reflected the values of an earlier time, a time increasingly out of fashion with those not of Walt's generation. Somehow, his films still made a lot of money.

A critic once quipped that Walt Disney had “nineteenth century emotions in conflict with a twenty-first century brain.” The characterization was apt. Disney may have been captivated by the new horizons offered by science and technology, but his moral principles dated from an age gone by.

Disney’s world was one where the conventional morality still applied, where two-parent families were still the norm, and where George Washington and Abraham Lincoln were still heroes. He grew up in an age when schoolchildren learned about the ideals of the American Revolution—and believed them. If you want to observe a friendly caricature of Disney’s mindset, watch Frank Capra’s Mr. Smith Goes to Washington. If you understand Jefferson Smith, you will have understood Walt Disney. (Incidentally, Lewis Foster, who won an Academy award for supplying the original story for Mr. Smith, later became a Disney writer.)

Honor. Duty. Chivalry. Patriotism. These were the undying themes underlying most Disney films. They were also heresies in the age Disney made his live-action features. Near the end of Disney’s life, American seemed engulfed in a rebellion against everything and everyone over the age of thirty. All that had been cherished in ages past was being thrown on the bonfires, as if Nathaniel Hawthorne’s horrific vision in his short story “Earth’s Holocaust” was at last coming to pass. The virtues of the old order became the crimes of the new, and our language quickly reflected the changes. Vandalism became self-expression; promiscuity, sexual liberation. In Vietnam, we became bogged down in a war against communism that no one seemed to want to fight; at home, our press plumbed new depths of cynicism and our courts let the criminals go free.

Or so it seemed to the vast “silent majority” of middle class, older, and ordinary Americans with whom Walter Elias Disney identified. Riots at home; disorder abroad; murder and rape in our own front yards. Defenders might have called it liberation, but for middle class Americans like Walt Disney (middle class in outlook, if not in economic status) mass suicide seemed nearer the truth.

And so Disney bluntly told people. In his Abraham Lincoln attraction at Disneyland, he even had Lincoln repeat portions of his Lyceum Address where he declared:

If destruction be our lot, we ourselves must be its author and its finisher. As a nation of free men, we must live through all time…or die by suicide.

During a press preview for the attraction, Disney told reporters that what Lincoln had to say “is a thing that we’ve got to listen to. I mean we don’t need to worry about the forces from outside. It’s the inside. Mass suicide he calls it. I agree with him.”

“It’s more or less what we do within ourselves that’s going to preserve what we have, rather than to be fearful of the enemy from without,” he told another group of journalists later the same day.

Yet though Walt might have thought that his country was propelling itself headlong toward annihilation, his studio seemed strangely oblivious to the crisis. Through the riots, the murders, and the sexual revolution, the Disney studio kept churning out its hopeful and admittedly sentimental films about lovable animals, chaste teenagers, small towns, and upright scoutmasters. To critics (as well as producers from other studios) such fare was bland, if not revolting. They looked down at Disney as the last prudish vestige from the cinema’s dark ages. They derided him for failing to come to grips with the realities of the new age, for having nothing to say about the plagues or perils of an increasingly nightmarish world.

The criticism wasn’t altogether fair. In many of his films and television productions, Disney was commenting on the changes wrenching American society. But more often than not he did so unobtrusively, cloaking his contemporary messages in the garb of fantasies or historical dramas.

Consider The Light in the Forest (1958), released in the midst of early civil rights struggles. Coming when it did, it is difficult to believe that this film was not intended as a commentary on contemporary racial tensions. The film centers on the plight of True Son, a white youth captured by Indians as a child and then raised by his captors as one of their own. As a teenager, he is compelled to return to his white family under the terms of a new peace treaty. He returns to face the prejudice and bigotry of the white settlers, prejudice and bigotry that only reinforce his own hatred for the settlers as barbarians.

There is enough blame to go around in this story. Each race believes the worst about the other. The whites view the Indians as savages because of the atrocities perpetrated by a few warriors; the Indians view the whites as cruel and barbaric because of their own atrocities against Indian women and children. The point, of course, is that human beings must be judged by individual merit rather than by the color of their skin. The Light in the Forest is a carefully crafted, sumptuously photographed, and beautifully written film (its script supplied by gifted Disney collaborator Lawrence Edward Watkin). The film’s only failing is its ending, where the most unrelentingly bigoted settler tritely repents after a fistfight with True Son. Still, the merits of the film more than make up for its final deficiency.

But if Disney’s historical dramas often said more than was immediately evident, so too did most of his fantasy-comedies. In The Absent-Minded Professor (1961) and Son of Flubber (1963), sprawling bureaucratic government was the target of the Disney satirical bite, as thick-headed bureaucrats in the Pentagon demonstrate they are more interested in playing golf than boosting the national defense. In these and other films, Disney’s prototypical hero was the lone entrepreneur, the individual patriotic American whose diligent efforts to save the nation are invariably stifled by governmental red tape, stupidity, and corruption.

One might add that throughout Disney’s pictures and television shows there is a recurrent antipathy toward bigness—whether it be big government, big cities, or big business. Disney viewed the enlarged scale of the modern world with apprehension. In his view men could not live as human beings when they were dwarfed by skyscrapers, oppressed by faceless bureaucracies, and herded into mass developments where they lived like strangers. Hence his perpetual return to small towns, individual families, and lone entrepreneurs. He purposely sketched the world on a smaller, more comprehensible scale in order to offer an alternative to the modern urban nightmare. (Even in Disneyland one finds this principle at work: its buildings are built to partial scale, not simply to save money, but in order to make the environment more friendly and inviting to visitors.)

This explains in part why many of Disney’s most unsympathetic characters are involved with big business—and why his social conservatism did not extend to a defense of corporate capitalism. He thought big business sapped the dignity from human life by enshrining materialism and power as its ultimate objectives. So in Mary Poppins we find a banker consumed by his desire to gain commercial success and professional stature. In The Absent-Minded Professor and Son of Flubber, we see ruthless tycoon Alonzo Hawks, the comic villain who would do anything to expand his business and who cares about no one but himself. (He snaps at his son at one point: “If I couldn’t deduct you, I’d disown you!”)

And in case anyone missed the point of such efforts, the message became explicit in the otherwise inconsequential TV feature For the Love of Willadean. There three children come across a former corporate executive who has lost his fortune and become a tramp. Played with characteristic quirkiness by Ed Wynn, the former tycoon tells the children how materialism consumed his previous life. “I was at the office all day and all night,” he says. “I had time for nothing but work. I was building an empire.” Then he lost it all—his wife, his money, his children. When he finally recognized that money and empires weren’t everything, he took a long walk under the stars and never came back.

Continued in "Walt Disney and Live Action"!

John West's analyses of Disney's live-action films are packed with little-known behind-the-scenes stories, such as Walt's initial disinterest in Old Yeller, which became a hit for the studio, and his stubborness in wanting to cast a Texas hound in the lead role.

Getting Old Yeller onto film proved to be a trying experience for producer Bill Anderson. Anderson first came across the novel when it was serialized in Collier’s. Reading it, he knew he had found material for a first-rate Disney theatrical feature. He immediately called the agent who was handling the property and asked to put a hold on it. Then he brought the subject up with Walt. That’s when the headaches started. Explained Anderson:

Three or four times a week Walt and I would meet together to discuss problems at the studio and the pictures I was involved in. I told him about Old Yeller and gave him the four issues of Collier’s where it appeared. I told him that I thought it would make a very strong story for us.

When several days passed and I didn’t hear anything from him, I thought it was rather strange. Then I found out that he was about to leave on a trip. Meanwhile, the agent called me back and said that MGM was interested in the story, and he wanted to know what we were going to do. So I told him we were going to buy the story. “I don’t have an answer yet, but we’re going to buy it.” And he said OK. And I said, “Now you’ve promised me. I have a hold on this until I release you.”

I finally confronted Walt. He called me in to have a drink, and I asked him about Old Yeller. He put his drink down and he said, “Well, there isn’t enough story there to make a television show, let alone a feature.”

I said, “Walt, I don’t think you read all four issues. You probably just read the first one.”

He pushed his chair back; I pushed mine back. “I guess the meeting’s over,” I said.

He said, “Yeah. I have nothing more to say.”

So I went home. I was furious. It was on the weekend, and I stayed out late Saturday night. Sunday morning I was sleeping late, and the phone rang. My wife was very kind to answer the phone, and she said “Oh, Bill, it’s Walt.” It was eight o’clock.

He said, “I’ve been waiting since five o’clock to talk to you.” I said, “Well, I’m sorry, if it was important, why didn’t you call me at five o’clock?”

“Buy that story.”

I said, “We’re going to have to pay more money for this story than we’ve paid for any of our other stories because other studios are involved.”

“I didn’t ask you how much it would cost. Buy that story.”

The friction over Old Yeller didn’t cease once Disney decided to do the story, however. The major sticking point turned out to be the casting of the major star—not human, but canine. Anderson and Disney vigorously disagreed about what type of dog should play the title role. Anderson continued:

Here’s where we had the real confrontation. Walt said, “That dog has to be a Texas hound”—because that was the way Fred Gipson had written it, and that was true to Texas. Well, I had been working with the director shooting tests of dogs. And I saw tests for several of these dogs, and they had no personality. They were not a dog you could really care about, and so I told Walt that at a luncheon. He pooh-poohed it.

“You can get any kind of personality you want out of a dog.”

I said to director Bob Stevenson, “You’ve seen all these tests—” But when he saw how Walt was, he wouldn’t speak up. I said, “Well, Walt, I’ll keep looking. But I’ve found another dog, Spike—and he’d make a wonderful Old Yeller.”

But no, it had to be this particular breed of hound. Hell, we had cast nearly all the parts, but we hadn’t cast the dog—or anyway, I wouldn’t cast the dog. Finally, I told Walt I was going to shoot a test of the dog I wanted.

“I don’t want you to shoot a test of him.”

“You mean you don’t even want me to test him?”

“I want a hound.”

And I said, “Well, I have a couple more hounds to test, but I may shoot the other one, too.” He didn’t say anything, because I was really doing something he said he didn’t want. Anyway, I shot the tests, and I showed them to him after dailies. He said, “He’s not the right dog. I like those hounds.” I said, “Well, I don’t.”

Now Robert Stevenson was there, and Walt asked him what he thought. And Bob said, “Well, I think we could make it with either one.”

I said, “Well, I just don’t think so.” And Walt said, “OK, I’ll look at them again. I’ll take them home tonight.

He took them home and Mrs. Disney saw them. Well, when Mrs. Disney saw big old Spike, Old Yeller, she said, “Well that’s the only dog I like. The rest of them, you can have them. I wouldn’t go see any of them, but that dog—that’s a wonderful dog!”

The next morning my phone rang. It was Walt. “You can have your damn dog! But he isn’t right for the picture!” That’s the kind of man he was. If he knew you were working really hard to make a picture better, he respected you.

Like many Disney productions at this time, most of Old Yeller was filmed at a ranch in southern California, doubling for nineteenth century Texas. The ranch used for this production was in Thousand Oaks. Today it is the North Ranch Golf Course; the Coates homestead was built on what is now the seventh and eighth holes.

As Anderson had predicted, the real star of the production was Spike, the big yellow dog who played Old Yeller. He was even treated like a star. He had his own make-up man, his own hairdresser, and even a look-alike stand-in. The investment was worth it. Though the entire cast for this film is outstanding, there is little question that it was Spike who stole the show.

Some of the credit for Spike’s outstanding performance, of course, should go to his director, Robert Stevenson. In 1978 Stevenson reminisced about working on Old Yeller and described how he directed the dog:

A dog can only do three things. [He can] turn his head in the right direction, cock his head, and bark. The dog in Old Yeller had the remarkable gift of putting his head to one side and looking quizzical. He was trained according to a particular note on a whistle. Whenever we wanted a quizzical close-up, we simply found that note on the whistle and played it.

Besides Spike the dog, the production required the use of several other kinds of animals, including a pack of wild pigs that attack Tommy Kirk in one sequence. The wild pigs were real. Twenty five of the nasty creatures were caught in central California and then hauled south to be used in the film, including one huge 200-lb swine that the film crew nicknamed Ivanhoe. For the safety of the actors, the pigs’ tusks were removed and replaced with rubber substitutes, but the procedure was done humanely. The pigs were given anesthesia and the operation was carried out under the supervision of a representative from the Humane Association.

The Disney studio always had a good reputation of how it treated the animals it used in its films. Unfortunately, it could not control the practices of its suppliers. During the production of Old Yeller, publicist Leonard Shannon remembered having to go out to a ranch where a bear used in the film was kept:

The conditions out there were appalling. You could see these poor animals. They had no water; they were panting, and in your heart, you wanted to call the Humane Association.

The climactic scene of the film, where Old Yeller is put to death, was an emotional scene to film. Actress Dorothy McGuire reported that “when the final moment came and Old Yeller had to be destroyed, we were all just flooded with tears—not as characters, but as human beings. It was such a hard thing to do.”

After the production was completed, Walt worried that the studio had made the film too well. “We’ve got too much sympathy for the dog,” he told Bill Anderson. “It probably won’t be one of our best repeat pictures.” Anderson agreed:

[H]e was right. It’s like my daughter. She won’t even show it to her daughter. She says, “You’ve changed a lot of things in pictures. You didn’t need to kill that dog! I won’t ever go see that picture again.” And it hasn’t proved to be a great repeat picture—for the very reason that people don’t want to go to a theater to cry.

Continued in "Walt Disney and Live Action"!

About Theme Park Press

Theme Park Press is the world's leading independent publisher of books about the Disney company, its history, its films and animation, and its theme parks. We make the happiest books on earth!

Our catalog includes guidebooks, memoirs, fiction, popular history, scholarly works, family favorites, and many other titles written by Disney Legends, Disney animators and artists, Mouseketeers, Cast Members, historians, academics, executives, prominent bloggers, and talented first-time authors.

We love chatting about what we do: drop us a line, any time.

Theme Park Press Books

The Unauthorized Story of Walt Disney's Haunted Mansion The Ride Delegate 501 Ways to Make the Most of Your Walt Disney World Vacation The Cotton Candy Road Trip The Wonderful World of Customer Service at Disney Disney Destinies Disney Melodies The Happiest Workplace on Earth Storm over the Bay A Historical Tour of Walt Disney World: Volume 1 Mouse in Transition Mouseketeers Down Under Murder in the Magic Kingdom Walt Disney and the Promise of Progress City Service with Character Son of Faster Cheaper A Tale of Two Resorts I Saw Ariel Do a Keg Stand The Adventures of Young Walt Disney Death in the Tragic Kingdom Two Girls and a Mouse Tale Ears & Bubbles The Easy Guide 2015 Who's the Leader of the Club? Disney's Hollywood Studios Funny Animals Life in the Mouse House The Book of Mouse Disney's Grand Tour The Accidental Mouseketeer The Vault of Walt: Volume 1 The Vault of Walt: Volume 2 The Vault of Walt: Volume 3 Who's Afraid of the Song of the South? Amber Earns Her Ears Ema Earns Her Ears Sara Earns Her Ears Katie Earns Her Ears Brittany Earns Her Ears Walt's People: Volume 1 Walt's People: Volume 2 Walt's People: Volume 13 Walt's People: Volume 14 Walt's People: Volume 15

Write for Theme Park Press

We're always in the market for new authors with great ideas. Or great authors with new ideas. Whichever type of author you are, we'd be happy to discuss your book. Before you contact us, however, please make sure you can answer "yes" to these threshold questions:

Is It Right for Us?

We specialize in books that have some connection to Disney or theme parks. Disney, of course, has become a broad topic, and encompasses not just theme parks and films but comic books, animation, and a big chunk of pop culture. Your book should fit into one (or more) of those broad categories.

Is It Going to Make Money?

There's never a guarantee that any book will make money, but certain types of books are less likely to do so than others. They include: hardcovers, books with color photos, and books that go on forever ("forever" as in 400+ pages). We won't automatically turn down these types of books, but you'll have to be a really good salesman to convince us.

Are You Great to Work With?

Writing books and publishing books should be fun. The last thing you want, and the last thing we want, is a contentious relationship. We work with authors who share our philosophy of no drama and zero attitude, and the desire for a respectful, realistic, mutually beneficial partnership.

If you said "yes" three times, please step inside.