- Visit the Imagineering Graveyard

- Now Sailing: "Skipper Stories" - Tales from the Jungle Cruise

- Coming Soon: The biography of Disney animator Jack Hannah

- Coming Soon: A Haunted Mansion anthology

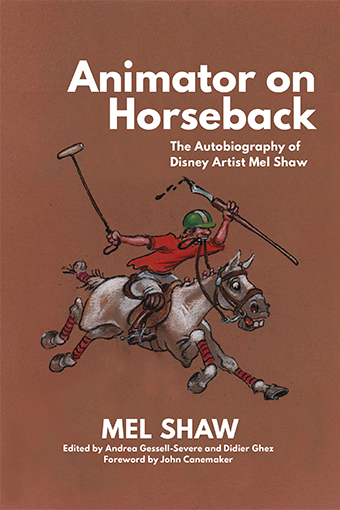

Animator on Horseback

The Autobiography of Disney Artist Mel Shaw

by Mel Shaw | Release Date: June 19, 2016 | Availability: Print

From Bambi to The Lion King

Mel Shaw's incredible career as a Disney artist and animator began in 1937 when Walt Disney offered him a job during a game of polo. Packed with nearly 400 illustrations and photos, including exclusive Disney concept art, Animator on Horseback is the story of Mel's life, in his own words.

When Mel arrived in Hollywood from Brooklyn, work for inexperienced animators wasn't easy to find. He landed a job at the Harman-Ising studio, but his career truly began when Walt Disney brought him on board to help with Bambi.

Mel left Disney not long afterward to work on his own projects, including Howdy Doody, but in 1974 he returned to mentor a new generation of animators, and he contributed to such modern Disney classics as The Rescuers, Beauty and the Beast, and The Lion King.

Mel's autobiography is a vivid, intensely personal recollection, with a cast of characters ranging from Orson Welles and Lord Mountbatten to Walt Disney and the artists and animators of the Disney studio, featuring stories about:

- The early days of animation in Hollywood, and the polo craze that brought Mel face-to-face with Walt Disney for the first time

- An intimate portrait of what it was like to work at the Disney Studio in the late 1930s, including a raucous trip to Mexico

- Life after Disney: active duty in the Pacific during World War II, and a stint with The Stars and Stripes

- The fortunes and failures of the Allen-Shaw Studio, Mel's joint venture with fellow animator Bob Allen

- Another intimate portrait of what it was like to work at the Disney Studio, thirty years later, when Mel returned to guide a new generation

A LIFE STORY OF POLO AND PIXIE DUST!

Table of Contents

Foreword

Introduction

Preface

Chapter 1: An Animator Grows in Brooklyn

Chapter 2: Cowboy Summer

Chapter 3: California Drawing

Chapter 4: A Passion for Polo

Chapter 5: The Disney Renaissance

Chapter 6: Tigers and Strikers

Chapter 7: Service on the Home Front

Chapter 8: The War Years: California to Calcutta

Chapter 9: In Ceylon, with Mountbatten

Chapter 10: Working for the Stars and Stripes

Chapter 11: The Allen-Shaw Studio

Chapter 12: The Carriage Trade

Chapter 13: The Disney Revival

Chapter 14: Final Frames

Foreword

Mel Shaw (1914–2012) was a master of film animation design and visual storytelling. His exploratory pastel drawings and paintings contain creative ideas and suggestions for imagery, staging, and color that inspired entire production crews. Scenarists, story artists and animators, producers and directors, even musicians benefited from his ever-fertile imagination.

Shaw’s art was mostly “unseen” in the sense that audiences did not view his original artwork on the screen, only adaptations of it by others. This seems a pity, especially when one sees the rare and tantalizing exception: the title sequence in Walt Disney’s 1977 feature The Rescuers, which consists of Shaw’s evocative pastels.

The sequence begins with minimal animation of a fearful little girl dropping a bottle containing a plea for help into a body of water, as the soundtrack sings “Won’t you rescue me?” The subsequent drama of the bottle’s perilous journey out onto the high seas, through weather stormy and calm, is shown in a sequential series of Mel Shaw’s rich, vibrantly colored pastel drawings, expertly staged for maximum emotional impact.

If an animated version of Debussy’s La Mer is ever again contemplated (as it was for the 1940 version of Fantasia), The Rescuers visualization demonstrates a brilliant way to depict the sea and its variable moods.

My original interest in reading Mel Shaw’s memoir, Animator on Horseback, was to feed my insatiable hunger for information about Hollywood animation’s so-called “golden days” of the 1930s and 40s. I was not disappointed.

Shaw began his film career devising title cards for silent movies. He describes in detail what it was like to be a youngster on staff at the early cartoon studios of Harman-Ising, Warner Bros., and MGM; and later, his work as a story sketch artist for Walt Disney’s Fantasia (1940) and Bambi (1942), among other films on through the 1990s.

Frank Thomas and Ollie Johnston, master animators on Bambi, once described Shaw as one of the few storymen who also did his own story sketches … a true natural artist who was particularly sensitive to the visual possibilities in the surroundings as well as to the appealing actions of the characters.

His work on the film earned “Melvin Shaw” his first screen credit in “Story Development”.

Shaw writes with clarity, candor, and dry humor about his remembrances of the animation world, its techniques and films, and the quirks and idiosyncrasies (both good and bad) of various personalities, such as Leon Schlesinger, Huge Harman and Rudy Ising, the Disney brothers, and numerous other producers, artists, and artisans. Particularly fascinating are anecdotes about working (and lunching) with Orson Welles, who contemplated an animated version of Antoine de Saint-Exupèry’s The Little Prince.

But Shaw’s life was long—97 years—and fully lived. In fact, he outlived both of his wives. It was a life that encompassed many an adventure with people outside of the animation field, who are well worth reading about. For this animator traveled widely and not just on horseback: Brooklyn, Utah, Hollywood, Mexico City, Calcutta, Ceylon, and Shanghai were among his ports of call.

He was born Melvin Schwartzman in Brooklyn, and the articulate artist’s prose offers vivid word pictures of his personal experiences during the Great Depression, which wiped out his family’s substantial finances, and their subsequent desperate struggle to survive in California. He and his father decided to change their surname, he explains, to avoid American anti-Semitism during the late 1930s as Hitler gained power in Europe.

Shaw’s drawing ability was discovered and flowered early, as did his lifelong love of horses. Sparked by a desire to become a cowboy, he ran away from home as a teenager to work on a Utah ranch breaking broncos and mending fences. A few years later, in 1937, his skill playing polo in Hollywood led to a run-in with a fellow polo enthusiast named Walt Disney, who angrily accused Shaw of riding “like a wild Indian!” Then offered him a job at his studio.

During World War II, Shaw served in the US Army Signal Corps as a filmmaker under Lord Louis Mountbatten, producing and directing films in live action with animated inserts of the Burma Campaign. Shaw is frank and vivid in his descriptions of life in the military in India, Burma, and China, and the horrors of war (including surviving “jungle rot”). His skill as a draftsman and storyteller also served him well as art director and cartoonist for The Stars & Stripes newspaper during a post-war military stint in Shanghai.

Augmenting his words in the memoir are wonderful illustrations by the author. The sketches demonstrate the skillful clarity and visual appeal Shaw brought to numerous film storyboards and conceptual drawings through the years.

His post-war life was not any less interesting. Shaw and a friend formed a company that became a success designing children’s toys, including early television’s Howdy Doody. They even created architecture and developed master plans for cities, including Century City, California. In 1974, his career came full circle when, after being away for a quarter century, he was invited back to work at The Walt Disney Studios.

Shaw’s storytelling visualizations and inspirational sketches added greatly to a new renaissance of Disney animated fare in the 1980s and 1990s, including Beauty and the Beast (1991) and The Lion King (1994), among other films. Producer Don Hahn, who produced both films, recalled that Shaw “[W]ould jump into a new film when it was still a blank piece of paper, and with his stunning work he’d show us all the visual possibilities of the idea.… He lived large and his contribution to film and animation is immeasurable.”

Writes Shaw: “When a man has practiced his craft for as many years as I have, it is the ultimate reward to be asked to return to lend a hand to the next generation.”

Mel Shaw’s memoir does much to slake the thirst of film historians and animation movie fans for first-hand reports by key players during Disney’s Golden Age. Like the admirable and worthy “unauthorized accounts” of former Disney story artist/writers Bill Peet and Jack Kinney, Shaw’s contribution is similarly articulate in both words and pictures, and equally illuminating.

But Mel Shaw places his animation experiences and the history of the art form in a larger perspective, by bookending and comparing his studio experiences at Golden Age Disney of the 1930s and 40s with New Golden Age Disney of the 1970s through the 90s. He also opens up his own life story significantly by contextualizing it within a world-events point-of-view.

Introduction

When my mother, Florence Lounsbery, married Mel in 1986, no one could have predicted the amazing journey I would share with my step-father, Melvin Shaw, and his book, Animator on Horseback.

Mel was the consummate storyteller, and it wasn’t long before my family asked him if he would consider writing his story. I doubt that Mel has ever said “no” to a project, and, two sentences later, I found myself agreeing to help him.

Our first attempt at writing together was loosely structured. He came to the project with energy and ideas that were already straining to be released on paper. So we began with a schedule of three two-hour sessions per week. The plan was for Mel to write a chapter and meet with me to review before I would type it up that evening. It was a struggle that first day. I could not read his handwriting and he found it impossible to write down his lengthy stories in long hand. He was much more comfortable telling his story so we began anew with him telling me his stories while I acted as his scribe on the computer. This is how we worked for the next eighteen years.

Each day, as we began to work, his urgency and energy would take over and he would often speed ahead, faster than I could type. Never showing his impatience when I slowed him down with questions, Mel would respectfully answer and elaborate until each story was told as he remembered.

One day he was retelling a story from his childhood. While I was typing and pausing to ask questions from time to time, I noticed that he had picked up a scrap of discarded paper to doodle as we talked. To my great astonishment, he was illustrating his story! I would ask a question and as he answered me, he would have his head down, working on a quick thumbnail sketch to emphasize what he was trying to convey. The sketches were coming, one after another, and soon I realized that the sketches were his way of completing the story. He was speaking through his art, his favorite form of self-expression. Those beautiful, random lines came together and combined to convey an expression, a feeling, an experience, a memory, a scene, and the collection ultimately became evidence that his artistic genius would forever be reflected in everything he touched. His art speaks of joy, pain, hope, fear, and all the human emotions we share. His story blends his words with his art to allow the reader to feel what he felt.

In the beginning, Animator on Horseback was meant to preserve his legacy for family, but with the help of good friends, Mel’s story is now shared with the world. Mel would be so pleased to thank Diane and Ron Miller for their encouragement and for introducing us to Didier Ghez, talented Disney historian and author who has picked up where we left off. Mel would also thank Don Hahn and Howard Green at The Walt Disney Studios, as they cooperated with Didier and Mel’s children, Rick Shaw and Melissa Couch, to see this project through.

Grateful for the fascinating twists and turns of our lives.

Grateful for Mel…a most positive, generous and kind man.

Mel Shaw

Mel Shaw was a Disney artist and animator who started work at the Disney Studio in 1937, left the company to pursue new projects, including his own studio, and returned in 1974 to guide a new generation of animators in the classic Disney tradition.

Mel meets Walt Disney on the polo field in 1937 and gets a job.

My polo was a weekend activity, but keeping my four horses conditioned for the stress of competition was a daily requirement. I had to arise at 5 every morning and gallop them through the hills of Encino and the surrounding walnut groves. I would ride and lead one on the gallop with my Dalmatian, Spots, close on our heels. Often I would pass my neighbors who were exercising their horses and celebrities like Clark Gable would enjoy the same early morning gallop in the hills. This was a demanding time because I had to remember that animation and art work were my career, and along with my daily work schedule, it required a great many evenings. I had just completed an MGM distribution short, Goldilocks and The Three Bears, in which the father bear’s voice was an imitation of Wally Beery.

Anticipating further production, the studio hired a fine portrait painter named Art Heinemann. Art enjoyed the fun aspects of the cartoon business and joined in our caricature wars. My caricature, portraying him as an ape man, brought about his immediate retaliation with his interpretation of me.

Even though we knew that our work was a necessity during the thirties, our enthusiasm for that work seemed to insulate us from the real world. Harman and Ising were unaware of another blow to come. MGM’s Fred Quimby cornered many of our studio’s personnel and enticed them to work directly for MGM in its new Culver City studio built just for animation. Harman-Ising Studios was close to folding. I was not invited to join this piracy, so again it looked like I was going to be waiting out another dry spell.

Walt’s studio was up against a tight schedule for shorts. They needed another cartoon short to satisfy their contract with RKO. Aware of Harman-Ising’s predicament, and his own needs, Ben Sharpsteen was sent over to supervise our work on the short, Merbabies. I did layouts, designed characters, and animated. With this additional work, Harman-Ising doors were kept open, in hopes of another release but it was not to be.

Shortly after completing Merbabies, I was scheduled to play in a big Sunday polo game at the Riviera. It was my assignment to play on a team with “Big Boy” Williams, Russ Havenstrite, and Tony Veene. Walt Disney was on the opposing team with Snowy Baker, Red Guy, and Tommy Cross.

At half time Walt came over and accused me of playing like a wild Indian. This was my first introduction to Walt Disney. Apparently, he didn’t like me using my larger horse to run him off the ball in front of a huge Sunday crowd, because he certainly knew exactly who I was. Then, lifting one eyebrow he asked, “What work are you doing now, Mel?” He knew that we had finished the Merbabies short for him, so I answered, “Nothing now, Walt.” To my surprise, he nonchalantly invited me to come over to his studio and talk to Dave Hand about working at Disney. Walt asked, “By the way, do you animate or do story?” I said, “I prefer developing characters and story ideas … I think this is my forte.” I always wondered if he was more impressed with my artwork or with my polo playing, but it didn’t matter because the work was sorely needed to keep up payments on my FHA home loan.

How could life have been better for a nineteen-year-old kid? I was my own man as I enjoyed the budding industry of animation in Hollywood, had my own ranch, and played in the exciting arena of the polo world. All the things I loved were wrapped up in one package. Art permeated everything I did. When I wanted to try a medium that the old masters used before the discovery of oil paints, I mixed tempera colors with egg as a binder, then I began a mural, four-feet tall and eight-feet long, on a piece of Masonite board that was covered with a plaster-like material called gesso. I sketched a scene depicting mythical centaurs playing a vicious game of polo. The only place I could easily work on such a project was in my tack room, so that was where I could be found. My dad also liked it there. Sometimes he would help me feed the horses, and he’d even, on occasion, go take a nap on the day bed in the tack room.

Continued in "Animator on Horseback"!

Mel recalls the growing concerns at the Disney Studio in the late 1930s over Bambi and Adolf Hitler.

By 1938, Walt had thrown everything he owned into the pot. The huge Burbank studio was almost complete and he had four features in production, but the best laid plans of Mickey Mouse and men “gang aft agley”. Europe was fifty percent of Walt’s market and it was quickly being destroyed by Hitler’s Panzer units and Stuka bombers. Now the remuneration from Walt’s pictures became a dribble, and not only that, but Fantasia, now completed, was recorded in stereo sound, which was not acceptable to the single sound systems of the day. Most theaters had a single speaker behind the screen, while Fantasia required seven speakers to give it a full symphonic effect. This meant that it had to be shown via a road show with an expensive array of sound equipment installed at each theater. It was not an economic possibility to show this film.

With the studio spread out between Hyperion and Seward Street, our Bambi unit would often be visited by Walt, Dave Hand, and Perce Pearce when they would come to view our progress at the Seward Street studio. We were used to working on our own, but recognized that Walt’s visits would quickly adjust and even change the direction of the film. One of the gag men drew up a sketch to memorialize such a visit. We knew who was boss. We were making good progress and all sequences were agreed upon, but at one point Walt thought more could be done with Bambi growing up. He suggested the young Bambi would step on an anthill causing a flood in the ant village below. We spent at least a month developing this sequence, then discarded it for straying too far from the storyline.

Delays had meant that Bambi was considerably over budget, so Walt called a meeting with Mr. Giannini of Bank of America. Giannini and his entourage arrived at our Seward Street studio dressed in dark suits and ties. They came to our unit so that Walt could use our storyboards to help him act out each sequence with great enthusiasm. His sales pitch was so convincing that I would have invested in the picture

myself if I had the wherewithal. We got the loan for a million dollars and production on Bambi continued.

Finally, amidst this financial crunch, our Bambi unit was the first to be moved into the new Burbank studio (even though it was still under construction). It was at the new studio that Rico Lebrun would set up a class on the large sound stage in the music recording building. The floor was partially covered with straw so the deer could be comfortable. The animators would situate chairs in a circle around them and listen to Rico’s instruction while they observed the movements of the deer. He was such a fine draftsman that he would make examples of anatomy for us to follow and he would come around and help us with the basic structure and action of the animal. He sketched as he lectured about the muscle and the flexibility of the limbs. And he even produced a sketch book pamphlet for us to follow. We knew he was trying to keep our drawings anatomically correct when the animators would want to return to the rubber and hose-like legs of a cartoon character. Our ultimate goal and challenge was to keep these sketches as realistic as possible, but still remember that we would have these animals speaking dialogue. It was a difficult balance to keep the story believable and not turn it into a typical cartoon. Of particular interest were the live fawns donated and sent to us by the state of Maine. It was a great help to observe these tame deer and capture the feel of their nature. One day Walt sent us one of his polo ponies so that we could study the anatomy of another four-legged animal. I made my rendering with blue and red pencil instead of the usual black charcoal.

In our new studio rooms there were many new innovations and luxuries for us to appreciate. The storyboards could now be hung on built-in hangers, our desks were constructed of beautifully polished hard wood, and upholstered chairs were designed to adjust to every comfortable “working” position. Talk of the plush chairs usually turned to teasing when the chairs’ “chaise longue” position tempted more than one of us to enjoy an after-lunch nap. One of the first napping casualties happened to be Roy Williams, a gag man working with me (later he became the “Big Mooseketeer” in Mickey Mouse Club). Walt just happened to be coming into our unit to see how we liked working in our new setup when he discovered Roy Williams snuggled deep in his new chair. Roy was the first but not the last victim of the luxurious chairs as we all found that our recliners could become a threat to our creativity. Unfortunately for Roy, this was not to be his only run-in with Walt.

Roy was a veritable gag machine and this reputation had earned him his place in the Story Department. However, at times his ideas were so wild that many directors would decline to have him in their department. But others, like myself, enjoyed the input and stimulation of his wit. Roy’s size and demeanor made him a perfect target for caricatures and studio pranks. On one particular day, Roy had left on his lunch hour to purchase some gardening equipment for his home. He stashed a wheelbarrow, bucket, watering hose, and some gardening equipment in his old Cadillac’s ample back seat. At the end of the day, as we left for home, one of the gagsters noted the wheelbarrow in the back of Roy’s car. He took the hose out and connected it to a nearby water outlet; then, leaving the wheelbarrow where it sat, he filled it with water. Later, when most of the Disney personnel had left, Roy emerged from the studio to find his car immovable. Red faced and furious, he glanced around and noticed a Model A Ford which looked like the one belonging to his biggest teaser. To vent his frustration and anger, Roy strode over to the car and gripped the headlights, perched on a bar on the front of the car. Using all his strength, he turned each of the headlights until they faced each other. Satisfied with his revenge, Roy then proceeded to use his new bucket to bail out his wheelbarrow so he could go home. Sadly for the hapless Roy, his problems were only beginning. Unbeknownst to him, the car he had mangled belonged to Walt’s secretary, so when Walt escorted his secretary to her car that evening and discovered that she had no headlights, Walt was upset. The next morning when Roy arrived at the studio, he learned that Walt had fired him. Walt had used this incident as an example to others to put an end to the outrageous pranks that plagued the studio. Some weeks later, Roy was rehired … and a more subdued gag man was he.

Gags and pranks aside, everyone at the studio kept a wary watch on the economy and how it affected our work and the future of the studio. Watching as Hitler moved through Europe was frightening to me. It filled the newsreels and we felt it at home and at work. Although the various productions moved ahead, the war was forcing Walt to scale down his training programs and personnel. Each day artists, writers, and office staff were let go, because without revenue from Fantasia and the European market, the studio had to trim back its overhead. Not everyone was pleased with Walt’s decision to scale down.

Continued in "Animator on Horseback"!

About Theme Park Press

Theme Park Press is the world's leading independent publisher of books about the Disney company, its history, its films and animation, and its theme parks. We make the happiest books on earth!

Our catalog includes guidebooks, memoirs, fiction, popular history, scholarly works, family favorites, and many other titles written by Disney Legends, Disney animators and artists, Mouseketeers, Cast Members, historians, academics, executives, prominent bloggers, and talented first-time authors.

We love chatting about what we do: drop us a line, any time.

Theme Park Press Books

The Unauthorized Story of Walt Disney's Haunted Mansion The Ride Delegate 501 Ways to Make the Most of Your Walt Disney World Vacation The Cotton Candy Road Trip The Wonderful World of Customer Service at Disney Disney Destinies Disney Melodies The Happiest Workplace on Earth Storm over the Bay A Historical Tour of Walt Disney World: Volume 1 Mouse in Transition Mouseketeers Down Under Murder in the Magic Kingdom Walt Disney and the Promise of Progress City Service with Character Son of Faster Cheaper A Tale of Two Resorts I Saw Ariel Do a Keg Stand The Adventures of Young Walt Disney Death in the Tragic Kingdom Two Girls and a Mouse Tale Ears & Bubbles The Easy Guide 2015 Who's the Leader of the Club? Disney's Hollywood Studios Funny Animals Life in the Mouse House The Book of Mouse Disney's Grand Tour The Accidental Mouseketeer The Vault of Walt: Volume 1 The Vault of Walt: Volume 2 The Vault of Walt: Volume 3 Who's Afraid of the Song of the South? Amber Earns Her Ears Ema Earns Her Ears Sara Earns Her Ears Katie Earns Her Ears Brittany Earns Her Ears Walt's People: Volume 1 Walt's People: Volume 2 Walt's People: Volume 13 Walt's People: Volume 14 Walt's People: Volume 15

Write for Theme Park Press

We're always in the market for new authors with great ideas. Or great authors with new ideas. Whichever type of author you are, we'd be happy to discuss your book. Before you contact us, however, please make sure you can answer "yes" to these threshold questions:

Is It Right for Us?

We specialize in books that have some connection to Disney or theme parks. Disney, of course, has become a broad topic, and encompasses not just theme parks and films but comic books, animation, and a big chunk of pop culture. Your book should fit into one (or more) of those broad categories.

Is It Going to Make Money?

There's never a guarantee that any book will make money, but certain types of books are less likely to do so than others. They include: hardcovers, books with color photos, and books that go on forever ("forever" as in 400+ pages). We won't automatically turn down these types of books, but you'll have to be a really good salesman to convince us.

Are You Great to Work With?

Writing books and publishing books should be fun. The last thing you want, and the last thing we want, is a contentious relationship. We work with authors who share our philosophy of no drama and zero attitude, and the desire for a respectful, realistic, mutually beneficial partnership.

If you said "yes" three times, please step inside.