- Visit the Imagineering Graveyard

- Now Sailing: "Skipper Stories" - Tales from the Jungle Cruise

- Coming Soon: The biography of Disney animator Jack Hannah

- Coming Soon: A Haunted Mansion anthology

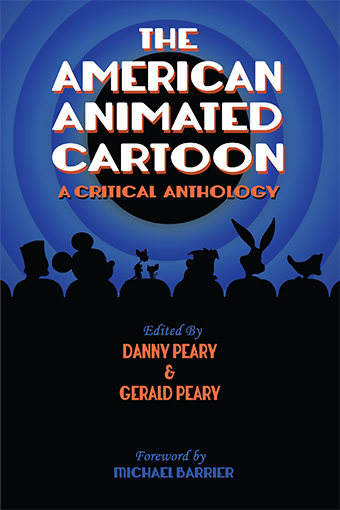

The American Animated Cartoon

A Critical Anthology

by Danny Peary & Gerald Peary | Release Date: August 5, 2017 | Availability: Print, Kindle

An Anthology of Animation

When you think about animated cartoons, you may think "Walt Disney" and call it a day. But if animation is a day, then Walt takes up just a few hours in the late morning. A lot came before, a lot came after.

In this re-release of their classic book, with a new foreword by Michael Barrier, editors Danny and Gerald Peary present an eclectic anthology of articles, analyses, and interviews by a well-regarded panel of film and animation historians.

Beginning with early practitioners like Winsor McCay and J.R. Bray, this episodic "history" of animated cartoons continues with stories about the major studios, including Disney, Warner Bros, Lantz, Fleischer, and UPA, and then focuses on individual characters and modern themes, such as women in animation.

From Dick Huemer, Vlad Tytla, Chuck Jones, Tex Avery, Bill Hanna, and Ralph Bakshi, to such films and characters as Snow White, Bambi, Dumbo, Bugs and Daffy, Popeye, Mighty Mouse, and Mr. Magoo, the rich tapestry of the American animated cartoon is unwoven for closer study and appreciation.

You're just in time for the dawn of animation...

Table of Contents

Publisher's Note

Foreword

Introduction

Part One: Early History

The Early History of Animation (Conrad Smith)

Winsor McCay (John Canemaker)

A Day with J.R. Bray (John Canemaker)

A Talk with Dick Huemer (Joe Adamson)

Just About Krazy (William Horrigan)

Miracles and Dreams (e.e. cummings)

Bibliography

Part Two: Walt Disney

Mickey, Walt, and Film Criticism, from Steamboat Willie to Bambi (Gregory A. Waller)

The Making of Cultural Myths: Walt Disney (Robert Sklar)

Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (Peter Brunette)

Dumbo (Michael Wilmington)

Vlad Tytla: Animation’s Michelangelo (John Canemaker)

Saccharine Symphony: Bambi (Manny Farber)

The Testimony of Walter E. Disney Before the House Committee on Un-American Activities

Bibliography

Part Three: Warner Brothers

Hugh Harman and Rudolf Ising at Warner Brothers (Tom Bertino)

Tex Arcana: The Cartoons of Tex Avery (Ronnie Schieb)

Chuck Jones Interviewed (Joe Adamson)

Robert McKimson Interviewed (Mark Nardone)

Robert Clampett (Patrick McGilligan)

Bugs and Daffy Go to War (Susan Elizabeth Dalton)

A Chat with Mel Blanc (Peter Stamelman)

Bibliography

Part Four: Other Studios

On Mighty Mouse (I. Klein)

Two Premieres: Disney and UPA (David Fisher)

An Interview with John and Faith Hubley (John D. Ford)

Reminiscing with Walter Lantz (Danny Peary)

Strike at the Fleischer Factory (Leslie Cabarga)

Bibliography

Part Five: Cartoon Characters

Seduced and Reduced: Female Animal Characters in Some Warners’ Cartoons (Sybil DelGaudio)

Meep-Meep! (Richard Thompson)

Pronoun Trouble (Richard Thompson)

Character Analysis of the Goof: June 1934 (Art Babbitt)

Mickey and Minnie (E.M. Forster)

Mickey vs. Popeye (William De Mille)

Memories of Mr. Magoo (Howard Rieder)

Bibliography

Part Six: Cartoon Today

A Conversation with Bill Hanna (Eugene Slafer)

Cartoon, Anti-Cartoon (George Griffin)

A Talk with Ralph Bakshi (Patrick McGilligan)

Women and Cartoon Animation, or Why Women Don’t Make Cartoons, or Do They? (Barbara Halperin Martineau)

The International Tournée of Animation: Talking with Prescott Wright (Joan Cohen)

Bibliography

General Bibliography

About the Contributors

About the Editors

Foreword

This book is a time capsule, a revealing look at the state of critical and historical writing about animation almost forty years ago.

Consider how little of consequence had been published about cartoons by 1980. The major publishing event of the preceding decade was Christopher Finch’s lavish coffee-table book for Abrams, The Art of Walt Disney (1973), which was followed three years later by Bob Thomas’s biography of Walt. The other cartoon studios were barely represented in books or, for that matter, magazines.

My magazine Funnyworld, which appeared sporadically throughout the 1970s, was one of the few publications that paid much attention to the likes of Looney Tunes, and it had a circulation of only a few thousand copies. I remember the stir created in 1975 when the slick magazine Film Comment devoted an entire issue to Hollywood cartoons, with a cover drawing by Chuck Jones. There was actually a moment, in the late 1970s, when there was a live possibility of an art book on the Warner Bros. cartoons, to be published by Time Warner’s book division—an episode I remember very well, because I was to have written the book. That bright candle was extinguished when someone in charge flinched at the cost of color printing.

Seeing the cartoons themselves was not all that easy in 1980. Videocassette recorders were on the market by then, but it would be a few years before the major copyright holders, Disney in particular, were comfortable with the idea of selling prerecorded tapes of their cartoons. Recording off the air was possible, of course, but was inevitably a hit-or-run affair, since so many short cartoons were dumped indiscriminately into TV ghettos when children were expected to be watching. The older cartoons, the ones that were often made with real artistry, had to compete with shoddy made-for-television fare that had the sole but sometimes decisive virtue of being new.

Things would change over the next few years, as cartoons became widely available on videotape and laserdiscs, and as a steady trickle of animation books grew in volume and importance. The first comprehensive survey of Hollywood animation’s history, Leonard Maltin’s Of Mice and Magic, was two years away when The American Animated Cartoon was published. John Canemaker, represented here by three articles, had published only one book at this point, a promotional volume for the feature Raggedy Ann & Andy, but important books on Winsor McCay and a host of Disney artists were soon to come.

It was inevitable, because so little of substance had been written about American studio animation by 1980, that a comprehensive survey like this one would have its dry spots, even or perhaps especially among the fifteen pieces written for the book. Cartoons have always tempted some writers into what can only be called academic prose, even when they have no academic affiliation. It’s little short of miraculous that so much that’s in this book is as good as it is, and often simply good, with no apologies needed. The interviews are especially noteworthy. In 1980, most of the leading lights of the great animation studios were still alive, and often eager to talk. Interviews like those here with Chuck Jones, Bob McKimson, and John and Faith Hubley are primary sources of a kind that have long since become impossible to duplicate.

I’m not represented in the book, and you might well ask why. In the late 1970s, when the Pearys were seeking contributors, I had just passed control of Funnyworld to a young businessman who was going to do great things with it, among them publishing an anthology of articles from the magazine. Never happened, but his pipe dream forestalled granting permission to use pieces from Funnyworld in this book.

In addition, I was deep in work then on my book that was eventually published as Hollywood Cartoons: American Animation in Its Golden Age. If I’d contributed to The American Animated Cartoon, I could have wound up competing with myself. Well...not exactly. I didn’t complete my book until 1997, and Oxford University Press published it in 1999, almost twenty years after the Pearys’ book.

I don’t know if The American Animated Cartoon was still in print in 1999, but I’m pleased that it’s back in print now. Hollywood Cartoons is still in print, too, and so I suppose the competition I feared forty years ago is now a reality—except for the fact that the number of books about animation is now vastly larger than it was in 1980, and books of all kinds must compete not just with other books but with the offerings of the internet. As between the two situations—one with a paucity of writings about animation, the other with a plentitude—I have no trouble preferring the latter.

Introduction

With The American Animated Cartoon, the reputation of the Walt Disney Studio as the only worthwhile producer of American cartoon animation is, we hope, laid to rest forever. We locate an extraordinarily productive alternative tradition outside of any studio, from pioneer Winsor McCay before World War I through such contemporary cartoonist independents as George Griffin and John and Faith Hubley. We acknowledge the achievements of non-Disney industry animators, from Paul Terry to Ralph Bakshi, from Walter Lantz to Hanna-Barbera, from J.R. Bray to UPA. Finally, we bring together articles in praise of the still astonishingly underrated Warner Brothers cartoon factory. These last essays pose a serious WB alternative to the artistic hegemony enjoyed by the Walt Disney Studio animation since the early 1930s.

This anthology presents a loosely conceived “auteurist” ladder of cartoon production, with such estimable figures as Winsor McCay, Chuck Jones, Tex Avery, Vlad Tytla, and Max Fleischer catapulting instantly into the pantheon; they are challenged by other animation giants such as Art Babbitt, Ralph Bakshi, Bob Clampett, Otto Messmer, and John Hubley. If we utilize Andrew Sarris’ provocative categories in The American Cinema (1968), are not Ub Iwerks, Robert McKimson, and Bob Cannon all Expressive Esoterica? And Frank Tashlin, too, as much for his Warners’ Porky Pigs as for his live-action Jerry Lewis pictures? Perhaps the more impersonal Walter Lantz and Friz Freleng and early Hanna-Barbera are metteurs, or skilled artisans, instead of true auteurs.

How to crack open the Disney monolith? Who is the auteur of Fantasia or Pinocchio or Bambi? Essays herein about Vlad Tytla and by Art Babbitt suggest paths for future animation historian: breaking down the Disney films into individual sequences and determining which animators worked on each. Only afterward can we discuss the artistry of such obviously inspired Disney animators as Ward Kimball, Frank Thomas, Shamus Culhane, Grim Natwick, and Ben Sharpsteen. For now, note the special and groundbreaking contributions of The American Animated Cartoon: a critical appreciation of Robert Clampett, the only interview with Robert McKimson, a rare essay on Krazy Kat cartoons, plus E. M. Forster and e. e. cummings on animation. Fifteen articles were prepared especially for this book. Only two essays have previously been anthologized.

Although The American Animated Cartoon celebrates its subject, we also keep in mind that cartoons shape consciousness, just as any film genre does; and animators are responsible to charges of gratuitous violence, racism, or sexism. The feminist critique by Sybil DelGaudio, “Seduced and Reduced: Female Animal Characters in Some Warners’ Cartoons,” is a role-model study that prefigures more careful scrutiny—political, ideological, semiological, psychoanalytic—of animated films to come.

On the same point, it is foolish to regard animation studios, businesses all, as repositories of fairy-tale, utopian values. In order to encourage an unclouded and non-nostalgic perspective on cartoon animation, we include two key historical pieces: a report on the labor strike at the Fleischer factory, and Walt Disney’s testimony alleging Communist infiltration of Hollywood, delivered voluntarily before the House Committee on Un-American Activities.

Danny Peary

Danny Peary has written or edited twenty-five books on movies and sports, including Close-Ups:The Movie Star Book, Cult Movies, Cult Movies 2, Cult Movies 3, Cult Movie Stars, Omni’s ScreenFlights/ScreenFantasies, Alternate Oscars, Tim McCarver’s Baseball for Brain Surgeons and Other Fans, and Jackie Robinson in Quotes. He lives in New York City.

Gerald Peary

Gerald Peary has written has written and edited nine books on the cinema. He is the programmer of the Boston University Cinematheque and a film critic for The Arts Fuse. He directed two feature documentaries, For the Love of Movies: the Story of American Film Criticism and Archie’s Betty, and he acted in the acclaimed independent feature, Computer Chess. He lives in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Disney as a manufacturer of cultural myth is nothing new. Robert Sklar takes it one step further, arguing that Walt gradually evolved from the creation of fantasy worlds to that of a vast but thematically coherent blueprint for an American utopia. (Sklar was the elder brother of the late Marty Sklar who spent over five decades working for Disney, rising as high in the company as president of Imagineering.)

The public first saw Mickey and Minnie in Steamboat Willie, in which the brilliant fusion of music with visual images adds immeasurably to the magic possibilities of plastic forms. A goat eats up Minnie’s sheet music. She swiftly twists its tail into a crank, turns it, and the notes come pouring out of the goat’s mouth as “Turkey in the Straw” (a scene reminiscent of Chaplin in The Tramp [1915] pumping a cow’s tail and filling his pail with milk). Mickey also made music by playing animals for different sounds—he got melody from, among others, the tails of suckling piglets and then from the teats of the sow.

Disney’s early films had raunchy scenes and outhouse humor. Some official responses, however, were even more ludicrous. Ohio banned a cartoon showing a cow reading Elinor Glyn’s novel of adultery, Three Weeks (1909)—perhaps because the Buckeye State thought it safe to drink milk only from monogamous cows. Then the Hays Office ordered Disney to take the udders off his cows: thereafter, no matter what they read, their milk at least would not harm anyone.

A taste for the macabre was another strong element in Disney’s style, and in early 1929 he launched the Silly Symphony series to express the grisly humor that was out of place in Mickey’s sunny world. The first Silly Symphony, The Skeleton Dance, depicted a nighttime outing of skeletons in a graveyard, dancing and cavorting to music. One skeleton makes music on another, like a xylophone. Hell’s Bells (also 1929) was even more grotesque: it takes place in hell, whose inhabitants include a three-headed dog and a dragon cow that gives the devil fiery milk (even Hades has its barnyard aspects).

Disney and his animators knew the value of shock and titillation before the feature producers, and though he often borrowed ideas from popular features, it is as likely that his cartoons fertilized the imaginations of other filmmakers in the early Depression years. In a 1930 Mickey Mouse comedy, Traffic Troubles, Mickey and Minnie crash into a truck loaded with chickens and end up covered with feathers, clucking and crowing—a comic fate Tod Browning transmuted into horror for Olga Baclanova two years later in Freaks.

Living and inanimate things reverse their roles. In The Opry House (1929) Mickey begins to play the piano, but the piano and its stool kick him out. The instrument plays its own keyboard with its front legs, and the stool dances. When it’s over, Mickey comes back out and all three take a bow. Mickey’s taxicab in Traffic Troubles bites a car to grab a parking place, licks a flat tire, and goes crazy after drinking “Dr. Pep’s Oil.” What have those fantasies to do with a culture’s myths and dreams?

Continued in "The American Animated Cartoon"!

For Disney fans, the most famous labor strike (if a strike can be "famous") was the one staged at the Walt Disney Studio in 1941. But there were other strikes against animation studios, ever bit as rancorous, such as the one outside the doors of the Fleischer Studio in New York City, four years earlier.

The animators stuck with Fleischer. Dave Tendlar insisted:

The strikers comprised only a small part of the studio employees (if not small in number, small in the functions they performed). There were a lot of people there who did not want to be organized. They were puzzled as to who these organizers were and so for a while two factions developed; those that went with the studio and those that did not. This ended the happy camaraderie around the studio and marked the first time that there were any ill feelings between studio members.

Some animators were sympathetic with the unionists but were afraid to impair their standing with Max and Dave by taking a stand. Alden Getz, who had worked for the Fleischers and joined the union, described a pamphlet that was sent around to employers on “How to Break a Strike” based on the U.S. Steel strike that year. One method was to fire several of the unionists as examples, giving arbitrary reasons for their release (under the Wagner Act no one could be fired for union activities). Another method was to hire thugs and detectives to infiltrate and make the going rough for the unionists. A guard could be posted at the front door of the building so no one could enter without a special pass issued from the studio. All this the Fleischers did.

CADU’s complaint turned to rebellion when fifteen Fleischer employees belonging to the union were fired. A strike was called and, on May 8, 1937 (the day of the Hindenburg dirigible disaster), picket lines formed outside the studio’s offices on 1600 Broadway and 49th Street. Some of the signs (painted in the studio’s art department and utilizing studio cardboard and wood) read: “I make millions laugh but the real joke is my salary.” and “We can’t get much spinach on salaries as low as $15.00 a week.” Accompanying striking Fleischerites were members of the Longshoreman’s Union, who helped out on the picket lines.

In the course of the demonstration that night, several nonstriking employees who tried to enter the building were engaged in fistfights with the strikers. Real trouble broke out later when ten policemen arrived to keep the picketers to one section of the sidewalk. The cops surrounded the picketers, knocking and kicking them about. A general free-for-all started and fists and placards were swung with abandon. Two thousand people gathered to watch the Fleischer employees utilizing their “twisker punches” on the police. “Peace” was restored after ten strikers were arrested and later four more were picked up for having allegedly assaulted a loyal Fleischer employee. Max issued a statement expressing shock that his workers felt underpaid. He claimed, “Inexperienced employees receiving the lowest pay are advanced after a short period to $40, $50 and some as high as $90 to $200 a week.”

The arrested strikers were taken to night court. Then they were set free in the early hours of the morning. After the first big ruckus with the police, James Hully, president of CADU, sent a letter to Mayor LaGuardia deploring the police brutality against members of his union. The letter proved effective because at the next picketing (at the Paramount and Roxy theatres that were running Popcye cartoons) the police stood by as strikers blocked the sidewalks, forcing the public onto the street. The picketers sang, “I’m Popeye the Union Man.”

On June 26, fifty strikers bought tickets to the Paramount theatre and began a raucous demonstration of booing and hissing as the Popeye cartoon flashed on the screen. One striker yelled, “Get that scab picture off the screen!” The din continued throughout the cartoon. At the end members of the audience broke into loud applause to drown out the opposition.

(Lou Appet, another member of the striking Fleischer staff, said that the demonstrators were successful in getting some theatres to boycott the Fleischer cartoons, and he believes that the studio was significantly hurt by it.)

The police broke up another noisy demonstration outside the Fleischer studio’s building on July 3 by arresting Ellen Jenson for felonious assault, biting and kicking an arresting officer on the left arm, and Helen Kligle for kicking and scratching Elizabeth Howson, a loyal employee. Seven men also were arrested.

The Fleischers began hiring cabs to pick up their employees. For a while CADU was able to get the cabdriver’s union to resist picking up the scab employees of the studio, but the drivers needed business and discontinued their help. A highlight of the strike was the stench-bombing of Dave Fleischer’s house. One of the strikers told him later that they meant to bomb Max’s house.

The strike was extremely hard on the union members, who received no pay throughout. Collections were taken up at other unions but because some had families to support, they broke down and went back to work. Looking back, however, those that were involved in the strike all seem to remember only the good times, full of optimism, determination, and companionship.

For example, there was a humorous day for the strikers, after the National Labor Relations Board finally stepped into the Fleischer labor dispute (after thirteen weeks of striking) and arranged for an election to be held within thirty days to see if the studio employees wanted CADU as their collective bargaining agent.

On August 5, 1937, they hitched a box kite covered with written appeals onto gas-filled balloons and hoisted it to the windows of the animation rooms.

At the predetermined time of 1:00 p.m., four reporters and a crowd that had gathered waited for the kite to arrive from the union’s 34th Street headquarters. At 1:30—still no kite. Then word came that one of the knots fastened to the kite had slipped and the balloons lifted the whole thing skyward. Left were thirteen balloons that read “Vote CADU” and these were let loose at the foot of the building to reach the animators’ windows. The few that did were shot down with paper clips and rubber bands. Most flew up and away from the building.

Continued in "The American Animated Cartoon"!

About Theme Park Press

Theme Park Press is the world's leading independent publisher of books about the Disney company, its history, its films and animation, and its theme parks. We make the happiest books on earth!

Our catalog includes guidebooks, memoirs, fiction, popular history, scholarly works, family favorites, and many other titles written by Disney Legends, Disney animators and artists, Mouseketeers, Cast Members, historians, academics, executives, prominent bloggers, and talented first-time authors.

We love chatting about what we do: drop us a line, any time.

Theme Park Press Books

The Unauthorized Story of Walt Disney's Haunted Mansion The Ride Delegate 501 Ways to Make the Most of Your Walt Disney World Vacation The Cotton Candy Road Trip The Wonderful World of Customer Service at Disney Disney Destinies Disney Melodies The Happiest Workplace on Earth Storm over the Bay A Historical Tour of Walt Disney World: Volume 1 Mouse in Transition Mouseketeers Down Under Murder in the Magic Kingdom Walt Disney and the Promise of Progress City Service with Character Son of Faster Cheaper A Tale of Two Resorts I Saw Ariel Do a Keg Stand The Adventures of Young Walt Disney Death in the Tragic Kingdom Two Girls and a Mouse Tale Ears & Bubbles The Easy Guide 2015 Who's the Leader of the Club? Disney's Hollywood Studios Funny Animals Life in the Mouse House The Book of Mouse Disney's Grand Tour The Accidental Mouseketeer The Vault of Walt: Volume 1 The Vault of Walt: Volume 2 The Vault of Walt: Volume 3 Who's Afraid of the Song of the South? Amber Earns Her Ears Ema Earns Her Ears Sara Earns Her Ears Katie Earns Her Ears Brittany Earns Her Ears Walt's People: Volume 1 Walt's People: Volume 2 Walt's People: Volume 13 Walt's People: Volume 14 Walt's People: Volume 15

Write for Theme Park Press

We're always in the market for new authors with great ideas. Or great authors with new ideas. Whichever type of author you are, we'd be happy to discuss your book. Before you contact us, however, please make sure you can answer "yes" to these threshold questions:

Is It Right for Us?

We specialize in books that have some connection to Disney or theme parks. Disney, of course, has become a broad topic, and encompasses not just theme parks and films but comic books, animation, and a big chunk of pop culture. Your book should fit into one (or more) of those broad categories.

Is It Going to Make Money?

There's never a guarantee that any book will make money, but certain types of books are less likely to do so than others. They include: hardcovers, books with color photos, and books that go on forever ("forever" as in 400+ pages). We won't automatically turn down these types of books, but you'll have to be a really good salesman to convince us.

Are You Great to Work With?

Writing books and publishing books should be fun. The last thing you want, and the last thing we want, is a contentious relationship. We work with authors who share our philosophy of no drama and zero attitude, and the desire for a respectful, realistic, mutually beneficial partnership.

If you said "yes" three times, please step inside.