- Visit the Imagineering Graveyard

- Now Sailing: "Skipper Stories" - Tales from the Jungle Cruise

- Coming Soon: The biography of Disney animator Jack Hannah

- Coming Soon: A Haunted Mansion anthology

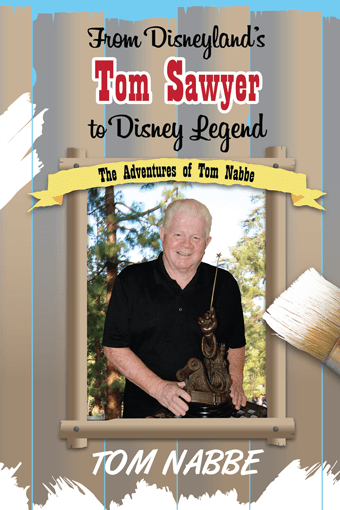

From Disneyland's Tom Sawyer to Disney Legend

The Adventures of Tom Nabbe

by Tom Nabbe | Release Date: September 7, 2015 | Availability: Print, Kindle

Walt Hired Me

In 1955, twelve-year-old Tom Nabbe was selling newspapers at Disneyland when he heard that Walt needed someone to play the role of Tom Sawyer. Tom pestered Walt until he got the job. Nearly fifty years later Tom retired, a Disney Legend.

You can't be Tom Sawyer forever. Eventually, you grow up. When Tom Nabbe became a little too tall, a little too deep-voiced, to continue his childhood on Tom Sawyer Island, Disney made him a ride operator. No more magazine covers for Tom. No more photos with celebrities. But it wasn't the end of Tom Nabbe's career; it was just the beginning.

In true American fashion, Tom pulled himself up by his bootstraps and rose through the Disney ranks. He became a manager at Disneyland, was instrumental in the opening of both the Magic Kingdom and Epcot in Florida, and was tapped as part of the Disney team sent to Paris to open the theme park there.

Tom's Disney adventures include:

- Watching Disneyland being built just down the road from his house, and later selling newspapers on Main Street, U.S.A.

- Finding fame as the namesake lord of Tom Sawyer Island

- Joining the early Disneyland "expatriates" who moved from Anaheim to Orlando and built the Magic Kingdom

- Taking a key role in the construction of the monorail system, and later the operation of Disney's enormous logistical warehouses

- Getting a well-deserved window on Main Street

Tom Nabbe's Disney story began as a fantasy and ended as the embodiment of the American dream. From straw hat to Disney Legend—these are The Adventures of Tom Nabbe!

Table of Contents

Foreword

Chapter 1: It All Started with a Paper Route

Chapter 2: My Foot in the Disneyland Door

Chapter 3: Disneyland Opens

Chapter 4: The Disneyland News

Chapter 5: Walt Hired Me

Chapter 6: I Am Tom Sawyer

Chapter 7: Tom Sawyer on His Own

Chapter 8: Dixieland at Disneyland

Chapter 9: Growing Up

Chapter 10: Too Big for My Straw Hat

Chapter 11: A New Tom in Town

Chapter 12: Signing Up with Uncle Sam

Chapter 13: The Screaming Tires, the Busting Glass

Chapter 14: Putting Tom Back Together Again

Chapter 15: Disneyland, Once More

Chapter 16: Go East, Young Man

Chapter 17: From Coast to Coast

Chapter 18: Testing the Monorail

Chapter 19: Building the Magic Kingdom

Chapter 20: Walt Disney World Opens

Chapter 21: My First Year at Walt Disney World

Chapter 22: The Nabbe Grabber

Chapter 23: Tom Sawyer Goes to Tomorrowland

Chapter 24: Jimmy Carter Goes to Disney World

Chapter 25: Building Big Thunder

Chapter 26: All Eyes on Epcot

Chapter 27: Working at the Warehouse

Chapter 28: Tom Becomes a Family Man

Chapter 29: Life After Epcot

Chapter 30: Of Windows, Legends, and Things

Appendix: The Next Tom Sawyer

Foreword

Tom Nabbe holds a unique place in the history of Walt Disney Parks and Resorts.

He began working in Disneyland at age 12 when the park opened in 1955. He was then hired by Walt Disney himself to be “Tom Sawyer”, official host of Tom Sawyer Island after it debuted in 1957.

And, when he retired with 48 years of Disney service, he was still just 60 years old, having worked in Disneyland, Walt Disney World, and Disneyland Paris.

As I look back on more than a half century of Disney memories, I realize that Tom and I have lived different but parallel Disney lives, affected in different ways by many of the same people, beginning with Walt Disney himself. Happily, our career paths crossed many times.

Our relationships with “Disney” began at the same time, in the spring of 1955. Tom’s family moved to Anaheim in January that year—exactly two years after I moved to the same, then little town of 19,000 people. We are almost exactly 20 years apart in age.

Tom’s family moved from another Los Angeles suburb because his mother wanted to live near this exciting new Disney project. They went into a brand-new “tract” house a few blocks north of the park. I had moved a few blocks farther north months before the Disneyland plans were announced and only a few months after moving to California to become a reporter for the Los Angeles Mirror-News.

In the spring of 1955, Disneyland was still very much unfinished. Industrious young Tom Nabbe began selling Sunday newspapers outside Disneyland construction gates to third-shift workers as they finished their night’s work in the round-the-clock race to finish by July.

At the same time I was planning a photo-feature story—the first in any of the metropolitan LA papers—to give readers a first look at the new “amusement park”. I recruited a 6-year-old neighbor boy as a model pretending to slip through the construction gates for a sneak peek. He posed in front of a half-finished Sleeping Beauty Castle, then fished in a waterless Frontierland creek and played a cowboy on a horseless stagecoach.

The Disneylander who helped us set it all up was Publicity Manager Eddie Meck, who was to play an important role in both our lives—Tom’s and mine.

Three months later I was assigned to cover the press-celebrity invitational opening of Disneyland on Sunday, July 17. All dressed up for the event, my wife, Gretta, and I arrived three hours ahead of the time set on our invitation. Eddie Meck was none too pleased at our early arrival, but led us to the press tent and issued a media badge. At that same moment an uninvited Tom Nabbe was sneaking along the fence outside Tomorrowland for a sneak peek at his already favorite ride, the Autopia cars.

Tom’s mother, an avid, star-struck autograph hound, was hanging around the front gate hoping for signatures from all the invited celebrities. Neither had an invitation. It was a long, hot day. While Tom and his mom were outside looking in, Gretta and I were lunching at the Red Wagon Inn near the center of the park, sitting a short distance from Eddie Fisher and Debbie Reynolds and other celebrities. We had prime rib and an hour later the restaurant ran out of food because the crowd was twice the number invited. Tom and his mother went hungry.

But their fortune smiled. Near 5 p.m., Tom’s mother sought comedian Danny Thomas’ autograph as he was leaving the park. He offered her his own two invitations, enabling Tom and Mom to race into the park only to discover Tom’s favorite ride, Autopia, was broken down. They rode the carousel instead.

Meanwhile, Gretta tired of the crowd and went home. I prowled around watching activities and the opening-day TV show. I went outside long enough to watch opening ceremonies in Town Square. At 5 p.m., I walked back onto Main Street and discovered the overheated day and intermittent ride breakdowns had cleared out most of the crowd. I called Gretta to come back. While Tom rode the carrousel, we were able to enjoy nearly all the attractions—many repaired after the guests left. We stayed until dark.

The next morning the news reviews were all about the overcrowding, the heat and traffic jams, and the operational disasters, The press panned it. I loved it, but my positive comment got lost in the rewrites. I returned that morning to see a relatively small crowd for the first public day.

But that was Tom Nabbe’s lucky day. He got a job with the newspaper concessionaire selling the Disneyland News at 10 cents each to guests lined up at ticket windows. He also worked at a newsstand on the west side of the Main Gate which is where Tom got to know Eddie Meck. Eddie, whose department also produced the Disneyland News as a promotional “guide” to the park, came each day to get copies of all the area newspapers to keep track of his publicity effort.

Frequently, when Eddie needed a model for a publicity photo, he would send for “that red-headed newsboy”. Tom worked through the summer and on weekends and holidays. A year later he had a new goal when he heard Walt was planning a “Tom Sawyer Island”. Nabbe began his campaign to become Tom Sawyer.

Early in 1956, months before the opening of Tom Sawyer’s Island, Eddie needed someone to dress up in overalls and straw hat and help him deliver invitations to news media around L.A. Naturally, he chose Tom Nabbe, who happily volunteered. They visited the Mirror-News city room, but I missed them. Early in 1957, I was named editor of the Mirror-News Southeast Zone edition and set up editorial offices in South Gate, about half way between downtown LA and Anaheim.

Nevertheless, I was invited to the June opening of Tom Sawyer Island and the press picnic which went with it. Tom was still awaiting Walt’s decision to name a “Tom”. So, Gretta and I opened our pink wicker picnic lunch basket in Holidayland. Two kids from Hannibal, Missouri, who portrayed that city’s Tom Sawyer and Becky Thatcher were brought in to preside at the Island premiere. Tom Nabbe was blocks away selling papers at Main Gate.

Not until the next day did Tom get his answer from Walt and began his new role as Tom Sawyer, greeting guests, posing for thousands of pictures, and helping youngsters go fishing in the Rivers of America.

In 1958, I made two additional visits to the park, but never Tom’s Frontierland. Both Tom and I remember vividly the 1959 grand opening of the monorail, Submarine Voyage, and Matterhorn Mountain. There was a spectacular parade with Meredith Wilson leading a “76-Trombones” marching band, but sill no meeting with Tom

By the time my children were the ideal “visit Disneyland age”, Tom had joined the U.S. Marine Corps for more than three years, 1965–68. During those years all hell broke loose for me. At least there were drastic changes in my life and at Disneyland.

The Mirror-News folded at the end of 1961, and I worked for a year as a feature writer for the Long Beach Press-Telegram. With Eddie Meck’s help, I mined Disneyland for numerous human interest stories—tour guides, characters, streetcar horses, and visiting kings and queens. At the end of the year I decided to take Eddie’s offer to be a publicity writer for Disneyland—an earth-shattering change for a veteran newsman. It was the best move I ever made.

Before Nabbe’s return in 1968, we had celebrated a year-long Tencennial Celebration for the park’s 10th anniversary, opened a new land (New Orleans Square), and added at least 14 major new Disney adventures, including four originally seen at the 1964–65 New York World’s Fair. Many incorporated the amazing new Disney Audio-Animatronics that imbued animals, plants, and humans into lifelike movements, beginning with the Enchanted Tiki Room. There were also a half-dozen new restaurants, four spectacular new parades, and major musical extravaganzas liker Dixieland at Disneyland and Big Band concerts. We set new attendance records every year.

Near the end of our 1965 Tencennial, Walt announced plans for his biggest dream, a gigantic resort and “future city” like no other, to be called Walt Disney World, in Florida

The end of 1966 brought the shock and tragedy of Walt Disney’s sudden passing after a two-month illness undisclosed until his death. It was the saddest time ever in “the happiest kingdom of all”. Tom was still a Marine, but stationed in San Deigo, California, near enough to share the grief with his Disneyland friends. We were all unsure of the future.

A year later, with Walt’s brother Roy O. Disney at the helm, work had resumed full-speed on the 30,000-acre Walt Disney World site near Orlando, Florida.

Meanwhile, nearing the end of his military career in 1968, Tom Nabbe was married, almost exactly 20 years after my own wedding. Later that year, he came back to Disneyland as a ride operator, but was soon swept into the Disney avalanche that was headed for Florida. In the fall of 1969, I was beginning work as the recently promoted publicity manager for Walt Disney World. Tom began training to become a supervisor on the Walt Disney World monorail system then already under construction.

I was busy hiring staff, spending half my time in Florida and traveling to major cities throughout the East to contact editors, travel writers, and radio-TV journalists touting the wonders of the new “Vacation Kingdom”. By mid-1970, I had moved my family and opened an office at Walt Disney World. Tom received his promotion to supervisor and moved to the Orlando area in January 1971 to begin work on the new monorails.

The Ridgway-Nabbe paths finally crossed in April 1971 when I was hosting a LOOK magazine photographer who, like I had been 16 years earlier, was given a first-ever opportunity to preview the resort. LOOK’s editors wanted to show the resort as it would look six months later. As Eddie Meck used to say, the impossible takes a little while. We sodded small areas to cover construction dust, used the almost completed city hall as a backdrop for Disney characters and Main Street vehicles, and hid other construction sore spots with everything from palm trees to sailboats.

That’s where Tom Nabbe came into the picture.

Our first shot was looking from a newly created white-sand beach across Bay Lake toward the spectacular Contemporary Hotel. From a distance it looked finished but for a few dump trucks on the ground and two giant construction cranes standing out like sore thumbs in the sky above the 13-story main tower shaped something like an Aztec pyramid.

We hid one crane with a convenient palm tree, but needed something else to obscure the other. I called for a sailboat to help fill space. I didn’t know that the skipper (chosen by Operations because he knew how to handle a sailboat) was Tom Nabbe. He was already pretty familiar with publicity pictures.

We did the shoot with pretty girls in swimsuits playing beach ball in the foreground while Tom kept his sails between the camera and the ugly crane. It all looked finished.

The next six months for Tom, myself, and the other 5,000 cast members in training for the October 1971 opening was all a blur. Many newsmen I brought in early in the year predicted it would never finish on time. Tom was caught up making sure the monorail trains were delivered on schedule and the “green” monorail pilots were turned into professionals. There was panic near the end when the station railings for the monorail failed to appear. Trains could not operate with passengers without the railings. They made it with two days to spare.

To avoid the debut disasters of Disneyland’s opening in 1955, we spread out our opening events over three weeks beginning October 1.

Tom, like most other Disney cast, were too busy to do interviews as they might have done at other times. They stayed that way for the next year. The news people went home with plenty of story material anyway.

A year later, Tom did find time to help our publicity efforts as we prepared to open Tom Sawyer Island in Florida. Again, the Tom Sawyer and Becky Thatcher selected each year by officials in Hannibal, Missouri, were brought in to preside at the opening, but this time Tom Nabbe joined them. We tapped him again as the boy Walt hired, when other writers were looking for a good feature story.

Another eight years went by with new attractions and parades almost every year. Less than ten years after opening, Tom transferred from monorails and other operations jobs to PICO, the branch of Disney Imagineering in charge of acquiring, shipping, and installing all the show sets. He was soon engulfed in warehousing and directing shipments of millions of items coming from Disneyland and almost anywhere else in the world to create Epcot as a revised version of Walt’s final dream for a an Experimental Prototype Community of Tomorrow. Tom played an important role in its quality and its success, and I got a promotion to director of publicity for Epcot and all the rest of Walt Disney World.

Our jobs expanded mightily in 1984 with the coming of Michael Eisner and Frank Wells to head the Walt Disney Company. Under their management, the resort added two more major Disney parks, two water parks, and another 15 spectacular new hotels, scores of other merchandise and entertainment operations in Florida, and, most ambitious of all, the creation of Disneyland Paris and its five spectacular resort hotels and campgrounds.

As years went by, I would run into Tom occasionally when I needed a prop from the huge warehouses under his management. He was no longer the red-haired kid once sought by Eddie Meck, but still had his freckles, smile, and boyish good humor.

It was a surprise when I ran into him nearly ten years after Epcot opened. I was in France managing publicity for a year. In January 1992, I found him by accident one day—didn’t know he was within 3000 miles. He was sitting in the traffic manager’s chair in a mammoth Disneyland Paris warehouse, again guiding millions of pieces from all over the world into their assigned places. But this time he had to do it in French. He found the props I needed for a publicity photo right away. He finished his job with the opening of the resort in April that year. I came back to Florida in July. He returned to warehousing and I to publicity.

Tom continued in his warehouse management role until retirement in 2003. Although technically I retired ten years earlier, I stayed on under contracts to continue working with Disney Publicity through the opening of Disney’s Animal Kingdom in Florida, Disney’s California Adventure and Grand Californian Hotel at Disneyland, and finally Hong Kong Disneyland, in 2005. Each of us put in more than four decades with Disney. I am still 20 years ahead of him in age. But maybe it works the other way.

Tom and I survived years of military service in two separate wars without a scratch. My two children worked at the resort during their college years. His son worked there for 12 years. I like to think we were present during the best of times, the most exciting, free-swinging, unbelievably explosive periods of growth, and even some moments shared with Walt.

We also share three very special honors. We were both named the by the company as Disney Legends, a group which includes some old Disney friends with records of important service to the company plus numerous Hollywood stars who have served Disney well. We were also named “Legends” by the Disney Fantasy Fan Club.

And best of all, we both have windows on Main Street in Walt Disney World’s Magic Kingdom. It follows a tradition begun by Walt when he placed the name of his father, Elias Disney, a contractor, on an “upstairs” window in Disneyland, plus other windows with the names of designers, builders, and others who played vital roles in creating the park. Eddie Meck’s window is also there.

In Florida my window reads, “Charles Ridgway, Press Agent, No Event Too Small”.

I will let Tom tell you about his.

Tom Nabbe

Tom Nabbe began working at Disneyland in 1955 and retired nearly 50 years later. He was the original Tom Sawyer, hired by Walt himself for the role. Nabbe was named a Disney Legend in 2005 and has a window on Main Street, U.S.A., in Walt Disney World’s Magic Kingdom (above the Main Street Cinema).

When Tom Sawyer Island first opened in Disneyland, guests could keep whatever fish they caught; young Tom Nabbe would even put the still-flopping fish in plastic bags for proud but possibly flummoxed guests. On hot days, however, the fish would soon stop flopping and begin stinking...

I loved my job out on the island. A lot of the visitors called me “Huck”, as I tended to work down by the rafts. If you really get down to the nitty-gritty, Huckleberry Finn was the one with the fire-red hair and the freckles, and Tom Sawyer was more of a sandy-haired blond boy. The guests never really went in for the particulars of Twain’s novel, and I made no attempt to clarify which character I was. I was whichever character they wanted me to be. To be true to the books, with my fire-red hair and freckles, I was probably more of a Huck. But Tom or Huck, I answered to anything except Becky Thatcher or Injun Joe.

I had a little trouble with reading, and to be honest, I wasn’t a real hot-shot student. My mind was better wired for geometry and trigonometry. If somebody asked me to read out loud in class, I’d break out into a cold sweat. But I did my best in school. I tried hard. That’s one of the things that Walt told me: “If I hire you, you’ve got to go to school and you you’ve got to maintain a ‘C’ average, and if you don’t maintain a ‘C’ average, you just can’t work for us.”

Somehow, Dick Nunis knew whenever I’d get a report card, because if I didn’t bring it in right away, he’d ask for it. Dick looked it over, too. I’m not sure whether he ever passed it on to Walt, but I’m sure he did tell Walt something like “Tom’s grades are still okay.”

Had my grades ever not been okay, Dick would have “elevated” my report card to Walt.

I’m not sure what would have happened then, whether I actually would have lost my job, but I’m glad that I never found out.

I also felt obligated to read the books on Tom Sawyer. I felt that I needed to know the stories, so I read both The Adventures of Tom Sawyer and its sequel, The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn.

Out on the island, Raleigh taught me how to build the fishing poles. How to set up the lines. How to put the line through the cork. People could fish on the island back then, cast out a line and pull in a catfish. We had two piers. I was to keep twenty-five poles on each. I kept all of the poles in good condition, all of the hooks and bait, too. Those types of things I learned from Raleigh.

Disney stocked the Rivers of America with plenty of catfish, bluegill, and sun perch, so guests had a pretty good chance of hooking a fish. When we first opened up Tom Sawyer Island, the policy was catch-and-clean. We had a little area to clean the fish if guests wanted to do that and had plastic bags to put the fish in. That only lasted a month or two because fish would start turning up in places where you didn’t want old, dead, smelly fish—like trashcans throughout the park.

To keep the fish where they belonged, we went to a catch-and-release program. For that to work, I had to de-barb each and every hook. It made it more difficult for guests to catch a fish, but the fish that were caught usually weren’t injured so badly that we couldn’t throw them back in the river for someone else to catch.

Around the perimeter of each of the piers they had little cans that were nailed to wooden poles, and I would fill those cans up with potting soil and then put in a healthy collection of worms. My boss at the time didn’t trust our worm supplier. Disney paid for worms by the flat, and each flat was supposed to have 350 worms in it. But how to know for sure?

I had to dig through each flat, which was full of rabbit manure, and count each worm. I’d pull each worm out, toss it into another flat full of potting soil, and keep an inventory.

As it turned out, the flats usually contained more than 350 worms, which made my boss happy but didn’t excite me one way or the other.

Keeping the soil moist for the worms was another part of my job each day. And if somebody didn’t want to bait a hook, that was part of my job, too. The thing I liked least was untangling fishing poles and their lines. As people would get tangled up real quick with one another, you had to give them two fresh poles, take the poles they had, and untangle the lines. I learned how to be patient doing that. Sitting there and untangling two or three fishing poles that were tangled together could be a challenge. Looking back on it, I probably should have just cut off the line and restrung the poles. But that wasn’t how we did things out on the island.

Eventually, it all became too much trouble and the fishing stopped altogether around the mid-1960s when they no longer had Tom Sawyer on the island.

Continued in "From Disneyland's Tom Sawyer to Disney Legend"!

When Walt Disney World opened, the company brought in Bob Hope, on the monorail, for the dedication ceremony of the Contemporary Hotel. Orlando, we have a problem...

To promote the opening of Walt Disney World, the company brought in some big-name celebrities, including Glen Campbell, Julie Andrews, Jonathan Winters, Rock Hudson, and Fred MacMurray. Some were brought in early to film segments before the opening. Some were there for the dedication ceremonies. But the event I remember most clearly involved comedian Bob Hope. He was to be the celebrity guest at the dedication of the Contemporary Resort.

A crew had built a stage in the Contemporary on the fourth floor and they wanted to exit Bob from the monorail onto the stage, where he would do a performance and tell a few jokes. It was all to be filmed for a later television special. On the morning of the Contemporary dedication, the monorail crew did a few practice rounds, and then they picked up Bob from the Polynesian, as the film crew wanted to capture Bob Hope coming off the monorail into the Contemporary concourse. The crew was set to capture a fabulous shot and a spectacular performance. There’s only one thing they hadn’t planned on: those air conditioning units mounted to the bottom of each monorail car.

I was at the Contemporary station to make sure the train would stop on its mark so that we could open the door and Bob Hope would step out and greet the audience and the cameras. As the monorail was on the beamway, bringing Bob toward the Contemporary, I had my radio earplug in and was ready. Bob arrived, stepped out, and waved, and then walked down to the stage. I was under the impression that everything was going fine, but then, over the radio, Jim Cora came on and said, “Hey, can you cut off that blower sound?”

“What blower sound?” I replied.

“Yeah. Whatever it is, it’s drowning out Bob’s speech. Can you fix that?”

I looked around and understood. “Yeah, I said. “I can.” So I reached up and I pushed the emergency stop button on the console in the station at the Contemporary. That disconnected 600 volts. When you drop 600 volts off, those air conditioners stop blowing immediately. Suddenly, I could hear every word that Bob Hope was saying with utter clarity. Now for the problem: the train was to leave in precisely fifteen minutes from the time Bob started his ceremony. This, I knew, wasn’t going to be easy.

Once I pushed the kill button, I picked up the phone, called the shop, and talked to a guy there named Ron Schtricten, who was the monorail shop maintenance supervisor. “Hey, look,” I said, “I don’t have a whole lot of time to explain, but I had to shut off the north rectifier.”

“You did what?” he said.

“I cut the power. Bob Hope is here. The cameras are on. You’ve got about eleven minutes to get there to reset it so we can drive this train offstage.”

Ron did what he had to do: he jumped on a little motor scooter and muscled over to the north service area (there are four rectifier zones and he went to the north service rectifier that covers the Contemporary). It wasn’t that far, maybe a quarter mile. Over the radio, he said: “I’m here. You tell me when you want the power back on.”

“OK,” I said.

I stood there, waiting for Jim Cora to come on and tell me to power up the train.

Bob Hope told a few more jokes. He said hello to a lot of people. He slowly made his way back up the stairs. Then Jim Cora got on the radio: “Let’s get that train going,” he said.

A couple of handlers loaded Bob back on the train.

I radioed Ron and told him to reset the rectifier.

Ron flipped the switches at the rectifier and powered everything up.

Right on cue, the train pulled out of the station.

Part of it was luck. Part of it was communication. Part of it was having a top-notch team. But if we had to try it a dozen more times—shutting down power and then bringing it back up—I doubt we could ever make it look so smooth.

There were other ceremonies—such as for the Polynesian and the Magic Kingdom—but I didn’t see those. For the Magic Kingdom ceremony, I was out at the monorail station, looking off at the park. But I knew what was going on inside. I could see the balloons and the doves that they released into the air. The doves circled above the station, a lovely sight, before heading to their coops backstage.

But the ceremony that stays with me was the Contemporary, bringing Bob Hope in and out on the monorail, and powering down the station just as the hotel was being dedicated.

Continued in "From Disneyland's Tom Sawyer to Disney Legend"!

About Theme Park Press

Theme Park Press is the world's leading independent publisher of books about the Disney company, its history, its films and animation, and its theme parks. We make the happiest books on earth!

Our catalog includes guidebooks, memoirs, fiction, popular history, scholarly works, family favorites, and many other titles written by Disney Legends, Disney animators and artists, Mouseketeers, Cast Members, historians, academics, executives, prominent bloggers, and talented first-time authors.

We love chatting about what we do: drop us a line, any time.

Theme Park Press Books

The Unauthorized Story of Walt Disney's Haunted Mansion The Ride Delegate 501 Ways to Make the Most of Your Walt Disney World Vacation The Cotton Candy Road Trip The Wonderful World of Customer Service at Disney Disney Destinies Disney Melodies The Happiest Workplace on Earth Storm over the Bay A Historical Tour of Walt Disney World: Volume 1 Mouse in Transition Mouseketeers Down Under Murder in the Magic Kingdom Walt Disney and the Promise of Progress City Service with Character Son of Faster Cheaper A Tale of Two Resorts I Saw Ariel Do a Keg Stand The Adventures of Young Walt Disney Death in the Tragic Kingdom Two Girls and a Mouse Tale Ears & Bubbles The Easy Guide 2015 Who's the Leader of the Club? Disney's Hollywood Studios Funny Animals Life in the Mouse House The Book of Mouse Disney's Grand Tour The Accidental Mouseketeer The Vault of Walt: Volume 1 The Vault of Walt: Volume 2 The Vault of Walt: Volume 3 Who's Afraid of the Song of the South? Amber Earns Her Ears Ema Earns Her Ears Sara Earns Her Ears Katie Earns Her Ears Brittany Earns Her Ears Walt's People: Volume 1 Walt's People: Volume 2 Walt's People: Volume 13 Walt's People: Volume 14 Walt's People: Volume 15

Write for Theme Park Press

We're always in the market for new authors with great ideas. Or great authors with new ideas. Whichever type of author you are, we'd be happy to discuss your book. Before you contact us, however, please make sure you can answer "yes" to these threshold questions:

Is It Right for Us?

We specialize in books that have some connection to Disney or theme parks. Disney, of course, has become a broad topic, and encompasses not just theme parks and films but comic books, animation, and a big chunk of pop culture. Your book should fit into one (or more) of those broad categories.

Is It Going to Make Money?

There's never a guarantee that any book will make money, but certain types of books are less likely to do so than others. They include: hardcovers, books with color photos, and books that go on forever ("forever" as in 400+ pages). We won't automatically turn down these types of books, but you'll have to be a really good salesman to convince us.

Are You Great to Work With?

Writing books and publishing books should be fun. The last thing you want, and the last thing we want, is a contentious relationship. We work with authors who share our philosophy of no drama and zero attitude, and the desire for a respectful, realistic, mutually beneficial partnership.

If you said "yes" three times, please step inside.