- Visit the Imagineering Graveyard

- Now Sailing: "Skipper Stories" - Tales from the Jungle Cruise

- Coming Soon: The biography of Disney animator Jack Hannah

- Coming Soon: A Haunted Mansion anthology

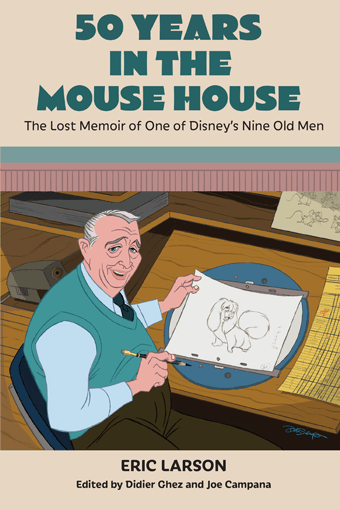

50 Years in the Mouse House

The Lost Memoir of One of Disney’s Nine Old Men

by Eric Larson | Release Date: June 24, 2015 | Availability: Print, Kindle

The Studio Life of a Disney Legend

Eric Larson, one of Walt Disney's famed "Nine Old Men", went to work at the studio in 1933 and left in 1986. He knew everyone at Disney who was anyone, and he kept a diary of the personalities, the pranks, and the politics. This is his warm, witty story.

In June 1933, young Eric Larson sent some of his sketches to the Disney Studio. A man named Dick Creedon liked what he saw and hired Larson as an inbetweener, the bottom of the pole at Disney, but that didn't last long. Soon, Larson became an assistant to top Disney animator Ham Luske, helping out on Fantasia.

From there, Larson met and worked with the very best at the studio, including Walt himself. Later, he gave a series of lectures on animation and established a talent program which brought new generations of gifted animators into the Disney fold.

In addition to Larson's memoirs, 50 Years in the Mouse House contains:

- A never-before-seen reproduction of the many notes and sketches in Larson's notebook from his 1942 trip to Mexico with Walt Disney

- All fourteen of Larson's influential Disney Studio lectures on animation

- An article by Disney historian J.B. Kaufman, a foreword by Disney Legend Burny Mattinson, and a remembrance by former Larson protege Dan Jeup

Enjoy this unique, entertaining, and educational perspective on the Disney Studio by one of its greatest talents!

Table of Contents

Foreword: Memories of Eric

Introduction: The Lost Memoir

A Short Biography of Eric Larson

50 Years in the Mouse House

Eric Larson Remembers

Larson in Mexico

Mexican Trip Notebook

Notes About Animation and Entertainment

The Eric Larson Lectures

Lecture I: Animation-The Phrasing of Action and Dialogue

Lecture II: Caricature and Entertainment

Lecture III: Acting for Animation

Lecture IV: Drawing for Animation

Lecture V: The Character and Texture of Action in Animation

Lecture VI: Movement, Rhythm, and Timing for Animation

Lecture VII: Staging, Anticipation, and Silhouette for Animation

Lecture VIII: Dialogue for Animation

Lecture IX: Music and the Animated Picture

Lecture X: Pose-to-Pose and Straight-Ahead Animation

Lecture XI: Angles, Straight Lines, and Curves

Lecture XII: Our Work Habits

Lecture XIII: Personality: A Command Performance

Lecture XIV: Be Yourself

Mentoring with Eric

Memo from Walt Disney to Don Graham

Acknowledgments

About the Editors

Foreword: Memories of Eric

I first met Eric Larson in the spring of 1954, just after starting to work in Marc Davis’ unit on Sleeping Beauty. Eric was the sole director on the picture at that time. Marc, who had finished animating the first couple of scenes of Briar Rose, brought Eric over to the room I shared with Clair Weeks, an animator who assisted Marc. After introductions, Marc flipped a couple of scenes for Eric’s approval. Eric was delighted by what he saw, but before he left, made time to welcome me onto the picture. He had such a warm, easy-going manner that instantly made you feel comfortable. Over the next several years, I saw Eric only occasionally, but he always greeted me like an old friend and made time to ask how I was getting on.

After Sleeping Beauty, Eric returned to animating on 101 Dalmatians, doing those warm sequences he was so good at, such as “the puppies in front of the TV set”. During that time, I freelanced around the Animation Department, working with several animators on different sequences of the picture.

It wasn’t until 1960, having finished work on 101 Dalmatians, that I returned from a two-week vacation to discover that there had been a huge layoff in Animation. Most of the animators and assistants I had worked with were gone. With fear and trepidation, I went to the office of the department head, Andy Engman, expecting the worst. Much to my shock and surprise, Andy told me that Eric Larson was looking for an assistant, and had asked for me to join him.

Our rooms were adjoining and Eric had just started working on the Ludwig Von Drake character, the star of Walt Disney’s Wonderful World of Color TV show for NBC. For the next 26 years, we were the best of friends. For the first twelve of those years, Eric was my mentor and I his assistant on the Disney TV show, the short Winnie the Pooh and the Honey Tree, along with five features: Sword in the Stone, Jungle Book, Aristocats, Mary Poppins, and Robin Hood. I also worked alongside him on the Oscar-winning short, It’s Tough to Be a Bird.

Of all the “Nine Old Men” (Disney’s core group of master animators), which included Eric, Woolie Reitherman, Marc Davis, Milt Kahl, Les Clark, John Lounsbery, Ward Kimball, Frank Thomas, and Ollie Johnston, I always felt that Eric was the most respected by his peers. Everyone else seemed to agree. He was the hub, and anyone with a problem could always go to him without being judged, and get an honest opinion and sound advice. Ever patient and accommodating, Eric would stop what he was doing and make the time for them. He seemed to take pride in helping you make your work the best that it could be. He always stressed “SINCERITY” (the honest believability in a scene), clear readable silhouettes with strong pose, and the clarity of action.

Each of Disney’s animators had their strengths; some were great draftsmen, others had great timing, and some excelled in design. And while Eric’s animation included all those qualities, his was the warmest and most sincere, much like the man himself.

There was nothing in animation or life that fazed him. He could animate heartwarming characters and scenes, such as Figaro in Pinocchio, who he portrayed as a five-year-old child, or fast action, such as the crazy Aracuan bird from The Three Caballeros. His brilliant work ran the gamut from the hilarious Bre’r Rabbit finding his “laughing place” in Song of the South to Peter Pan flying over the city of London, and the sassy dog named Peg singing “He’s a Tramp”. Eric could do it all!

After working together for about six months or so, Eric and I started to have an occasional lunch together. This soon turned into a regular event. There were two local watering holes in Toluca Lake near the Studio at that time that were frequented by the animators. One was an Italian restaurant specializing in seafood called Sorrentino’s; the other was Alphonse, which was famous for its cannelloni. Eric paid for my lunch for the next year or so, until I got a raise. He had his own booth by the bar. After ordering his customary sherry, we would talk about the Studio and family as we greeted such other regulars as Marc Davis and Milt Kahl. Many Hollywood stars and celebrities would also dine there. Eric treated me like the son he never had.

It was during the making of Robin Hood that a couple of the top animators, including Hal King and Les Clark, retired, prompting the Studio to realize that they needed to develop a new group of replacements. A program was set up to give the first opportunity to some of the assistants to the Nine Old Men. Each group of assistants had four weeks to complete an animation test of their own choosing, which was then judged by the top animators. Unfortunately, this group of assistants all failed—not because their animation was poor (as many had been animating for years), but because the “judges” didn’t want to lose their assistants. After a brief admonishment by Don Duckwall, manager of the Animation Department, the next group of assistants fared better, including Don Bluth, Walt Stanchfield, Chuck Williams, and myself. Many of the “Old Men” had little interest in helping or teaching aspiring animators, and it soon became apparent that if you wanted to succeed, Eric was the go-to guy. He had the patience and gift of teaching, a role he thoroughly enjoyed. Never at a loss, he could impart a very simple, logical way of animating a scene and give it lots of feeling.

In 1973, Eric moved up to the second floor to establish a Recruitment Training program for animators. Periodically, he would travel around the country, visiting different colleges and art schools in search of talented prospects. Soon, he assembled a group of young artists that he nurtured and taught, who would become top Disney animators. This illustrious group included Glen Keane, Mark Henn, and Dale Baer. Meanwhile, I went on to animate on Robin Hood and Winnie the Pooh and Tigger Too before being asked by director Woolie Reitherman to storyboard on The Rescuers. All during this time, Eric and I continued our daily lunch.

Even though Eric was involved with the training program, Woolie (who was directing The Rescuers) asked him to join Mel Shaw and me on the opening title sequence where we follow the bottle containing a letter for help on its ocean journey to New York City. Woolie wanted to use Mel’s pastels under the titles for the picture’s opening. I suggested story sketches that Mel rendered, while Eric, always a master of timing, planned the shots to work with the music.

One day at lunch, Eric expressed his concern about how to keep the new trainees, who were doing pointless test after test, interested in learning how to animate. I suggested that he might consider getting a story that they could work on that might actually be released as a featurette. Eric was excited about the idea and talked to Pete Young, a talented up-and-coming new storyman. Pete suggested The Small One, which he had used as a storyboarding test. With veteran pros Vance Gerry and Mel Shaw doing visual development, Pete and Vance worked out a wonderful story. Management liked the pitch and Eric got the go-ahead to use his trainees to animate it. Eric would teach and direct.

Eric then asked Woolie if he could borrow me from storyboarding on The Fox and the Hound to help on The Small One for a few months. I was to break down each scene on the storyboard into key poses, which the trainees could use as a guide for animation.

About one month into production, the project was generating lots of excitement as the new trainees rose to the challenge and Eric began handing out scenes. Around this same time, Don Bluth and his crew had just finished animation on Pete’s Dragon.

All of the excitement seemed to unravel over a weekend. I returned to work on Monday and, much to my shock and surprise, my office was stripped bare of every piece of work pertaining to The Small One. Walking into Eric’s office, and the trainee’s rooms, I found the same bare walls. I waited for Eric to arrive. When he walked in, he was as confused and dumbfounded as I was as he surveyed the rooms. He called Don Duckwall, who came down immediately. Behind closed doors, Duckwall apologized and explained that Don Bluth had gone to Ron Miller (then head of Walt Disney Productions) and told him that he wanted to do the film because he felt that Eric and his crew of fledgling animators were not up to the task. Miller, convinced that Bluth and his team represented the new wave of Disney animators, gave his okay for Bluth to take over the project. That weekend, Bluth and company had come in to remove everything from The Small One that was in our rooms on the second floor, and moved it to their offices on the first floor.

After Duckwall left, Eric came into my room and relayed what he had just been told. He was almost in tears and clearly felt betrayed. Nobody ever apologized or gave any other explanation.

The news was met with disbelief and disappointment. It was hard to imagine someone doing this to Eric.

I returned to Woolie’s unit and continued storyboarding on The Fox and the Hound through its completion. Following that, I worked briefly on the story for The Black Cauldron.

In 1981, I presented an idea for a featurette, Mickey’s Christmas Carol, to Ron Miller. After three weeks of storyboarding, he appointed me director and several months later, producer. I was working with many of the new animators, including Glen Keane, Mark Henn, Randy Cartwright, and John Lasseter. Since Eric and I were very close, I always knew I could count on him for help. So when I had a difference of opinion with one of the new animators as to how a scene should be animated, rather than get into a heated argument about it (and knowing that Eric was their animation god), I’d tell them to go upstairs to see Eric, and I would accept whatever he says. As soon as the animator would leave my office, I’d call Eric and explain what I wanted. He’d say, “Don’t worry. I’ll take care of it.” Later, the animator would return and say, “I tried and tried, but Eric agreed with your way.” How delightful! Throughout the film, I knew I could count on Eric’s help. He even took on a directing role for the dancing sequence, and enlisted his new trainees to do a fantastic job.

After Mickey’s Christmas Carol, I joined the crew of Basil of Baker Street. While we spent the next year developing the story, Eric continued recruiting and training as the company went through a dark period of financial and managerial shake-up. In the fall of 1984, Ron Miller left the Studio, while Roy E. Disney brought in a new management team headed by Michael Eisner, Frank Wells, and Jeffrey Katzenberg. Shortly after, it was decided to move the entire Animation Department from our home at the Studio lot (where it had been for the past 45 years) to a warehouse in Glendale. Eric moved with us, and continued working with the animators to help them solve their problems during the making of the picture. Happily, our daily lunch get-togethers continued, too.

It was in early 1986, as The Great Mouse Detective (as it was un-popularly retitled) neared completion, that Eric made the decision to retire. He had often talked about retirement, especially after his wife, Gertrude, passed away, but I always encouraged him to stay. I needed him, and I worried what would happen to him if he wasn’t doing what he loved most, working with the young talent and going to lunch with me every day. Eric passed away two years later at age 83.

Throughout the years, Eric had often told me that when he retired, he wanted to write his book, 50 Years in the Mouse House. The idea for the book came from Wilfred Jackson, one of Walt’s earliest and most respected directors. Wilfred advised Eric to keep a detailed, daily diary of what happened at the Studio. He explained that several years earlier, he had a heated confrontation with Walt over a change that Walt had wanted and that Wilfred hadn’t made. Walt remembered it one way and Wilfred another. From that day on, Wilfred said he kept a detailed diary to settle any future arguments, and encouraged Eric to do the same. Eric took the suggestion and dutifully kept a diary, saying he never realized how many times over the years he had referred to it in order to reinforce his memory. But then it struck him that the real value would be to write a book, 50 Years in the Mouse House.

Thanks to the tireless efforts of historian and researcher extraordinaire Didier Ghez, Eric’s memoirs and sage advice will finally see the light of day. Now we can all learn from this wonderful man and hear of his adventures as an animation pioneer. Enjoy!

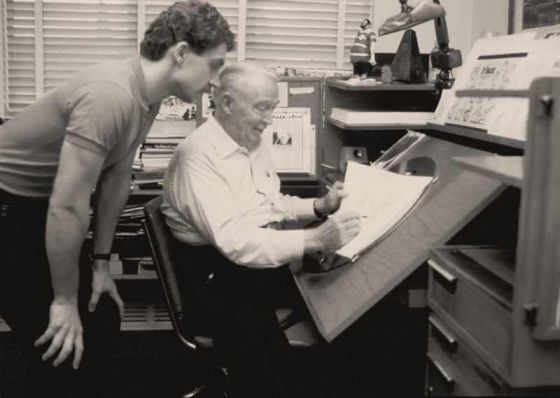

Eric Larson with Burny Mattinson, 1983.

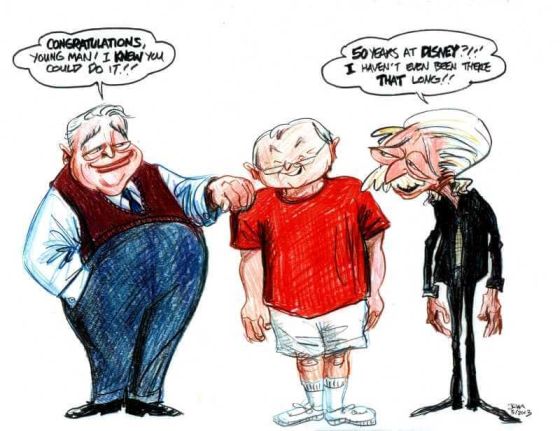

Eric Larson, left; Burny Mattinson, center; Joe Grant, right. (Caricature by John Musker)

Introduction: The Lost Memoir

I became obsessed with Disney Legend Eric Larson’s lost memoir back in 2008. I was interviewing artist Burny Mattinson when one of his answers gave me a jolt. Burny had just told me that when he was working with Eric, Eric was actually writing his memoir. An unpublished autobiography by one of Disney’s Nine Old Men? I simply could not believe my ears. Was Burny correct? Could this book really exist? If so, I had to try and locate it.

I spoke with Disney historian John Canemaker, author of the seminal book Walt Disney’s Nine Old Men and the Art of Animation. And knowing that John was one of the most thorough animation historians around, I wondered if he knew anything about this potential treasure. John mentioned that when he was writing his book he had tried to locate this rumored manuscript, without success.

Five years later I was still wondering if the manuscript actually existed, when I attended a luncheon with some fellow Disney historians and Disney history enthusiasts, and discussed the matter with them. Two of them, who had worked with Eric, confirmed that they had actually seen the manuscript in Eric’s office in the early 1980s. It would still be a search for a needle in a haystack, but now, at least I knew that the needle existed.

My good friend and fellow Disney historian Joe Campana was attending the same luncheon. When we left the event I told him that I thought we really needed to find a way to locate the manuscript. The following day Joe discovered that Eric had one sibling who was still alive—his younger brother, Lanol Larson, then in his 90s. And Joe had found Lanol’s phone number. We called right away and got no answer, but anxiously left a message. A few days later, late in the evening, Joe got a call on his mobile. It was Lanol and he said that he indeed had some papers of Eric’s. He had looked through them once or twice and recalled them as being Eric’s notes of his time at the Disney Studio! These papers had been sitting in a red suitcase, preserved carefully for twenty-five years.

Joe and I were ecstatic. A few months later the red suitcase was hand-delivered to Joe’s office by Lanol’s son, Bryan. It was then that we learned that we had truly hit pay-dirt, from a historical standpoint. The suitcase contained several legal notepads comprising the manuscript for Eric’s memoir, 50 Years in the Mouse House, a very personal view of life at the Studio from the 1930s to the late 1950s, as well as Eric’s diary of his 1942 trip to Mexico for Disney and miscellaneous writings about animation and the art of entertainment. Most of the documents were in draft form, some of them existed in multiple versions, but all of them contained real treasures.

Joe and I knew we had to organize and edit this marvelous material for your enjoyment. We also knew that we had to enhance the core content with some amount of “bonus material”. We spent a year doing so, helped by Disney historian J.B. Kaufman and by artists who knew Eric, like Burny Mattinson, Andreas Deja, and Dan Jeup.

Eric was a great writer and knew how to share his memories and wisdom with both clarity and deadpan wit.

More than eighty years after Eric Larson first set foot in the Disney Studio, it is our pleasure to offer you the chance to spend time with him and to share those memories of his 50 years in the Mouse House.

Disney animator Andreas Deja, left, with Eric Larson, 1980.

Eric Larson

Toward the end of his enduring career at The Walt Disney Studios, animator Eric Larson became a gentle and devoted mentor to the next generation of up-and-coming Disney artists. Former student Andreas Deja, who animated such Disney characters as Jafar from Aladdin and Scar in The Lion King, remembered Eric as “the best animation teacher ever.” “No one was more concerned with passing on the Disney legacy than Eric,” Deja once said.

In the late 1970s, Eric expanded the Studio’s Talent Program to find and train new and talented animators from colleges and art schools across the nation. This program, which still exists today, came at a crucial juncture in Disney’s history, when many veteran animators were stepping down from their drawing boards. Subsequently, through his close work with young animators, Eric helped preserve the integrity of Disney animation for generations to come.

Born in Cleveland, Utah, in 1905, Eric avidly read comic humor magazines, such as Punch and Judge, while growing up on the plains. After high school, he went on to major in journalism at the University of Utah. While there, Eric edited the campus magazine and won a reputation as a creative humorist in both literature and graphic arts. He also sketched cartoons, which appeared in the local Deseret News.

After graduation, Eric traveled around America for a year freelancing for various magazines and, in 1933, landed in Los Angeles. There, he developed an adventure serial for KHJ Radio, called The Trail of the Viking. That same year, taking the advice of a friend who was familiar with his exceptional drawing skill, Eric decided to submit some of his sketches to the Walt Disney Studio. He was hired as an assistant animator, and his journalism aspirations changed for good.

Over the years, Eric animated on such feature films as Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, Fantasia, Bambi, Cinderella, Alice in Wonderland, Peter Pan, Lady and the Tramp, Sleeping Beauty, and The Jungle Book, as well as nearly 20 shorts and six television specials. Later, he served as a consultant on The Black Cauldron and The Great Mouse Detective.

After 52 years at Disney, Eric retired in 1986. In an interview at that time, he said, “The important thing is not how long I’ve been here, but how much I’ve enjoyed it and what I’ve accomplished in all that time. When I think about my contribution to the animation that people enjoy so much, it makes me feel good.”

Eric Larson passed away in La Cañada Flintridge, California, on October 25, 1988.

Source: Eric Larson's Disney Legends page.

Eric Larson recalls Walt's frustration with the slow progress on the animation of Sleeping Beauty.

In the mid-1950s when we were hard at work on Sleeping Beauty, the story went around one day that Walt had met Marc Davis and Milt Kahl on the stairs and, in his inimitable way, put the knife to them, and once in up to the hilt proceeded in his sarcastic way to twist it full turn with: “What the hell are you bastards doing with all that heavy ponderous animation you’re doing in Sleeping Beauty? You’re costing us a fortune! Why hell: We’re putting out live-action pictures on short schedules and damn cheap. You guys are going to bankrupt us!”

Sleeping Beauty was that kind of picture…an epic, to later be hailed as a classic. I was a director on it and I shall never forget how Walt poured out his wishes and hopes for it as he and I left what had been a very successful and exciting story meeting on Sequence 8. Sequence 8 was the first to be put into actual production and my unit was to do it.

The development of the personality and physical makeup of the characters in our animated feature films has never been easy. It has always been a challenge! It has all come about through the hard work of the animator, working with all the great inspiration gleaned from Walt, the storymen, the director, the dialogue voices, the musicians and other animators, and then adding his own ideas and interpretations to bring life, heart, personality, and believability to the screen in linear drawings. Sequence 8 was such a proving ground for the girl and boy in this great film.

It begins with the girl, christened Aurora, in a pensive, romantic mood, strolling through the storybook forest, having been graciously, but firmly, sent on a berry-picking errand by her devoted godmothers, the three good fairies who were excitedly planning a surprise party for her on this, her sixteenth birthday. “But I picked berries yesterday,” the girl insisted. “Oh, but we need more…lots, lots more,” was their reply as they gently edged her out of the house.

The fairies, living as little old women in the forest, had protected and cared for Aurora for the past sixteen years, and now with this most important birthday at hand and the anticipated possibility of it passing without the fulfillment of the curse which the wicked fairy, Maleficent, had placed upon the baby girl at her christening, they were happy and hopeful. “For upon her sixteenth birthday,” Maleficent had predicted, “she shall prick her finger on the spindle of the spinning wheel and die!”

In the forest, Aurora paused in the course of her berry picking with her animal friends grouped around her, anxiously listening to every word she told them about her prince. “He’s tall and handsome, and when he takes me in his arms…I wake up.” Greatly disappointed, the animals contrive a prince for her. She happily joins in the charade with song and dance, but the make-believe game is interrupted by the appearance of the real prince, unknown to her, but to whom she was betrothed through parental wishes and agreement on the day she was christened. Remembering she had been constantly cautioned by her godmother to speak to no one, she breaks away, but in answer to his pleas and with hesitation she finally tells him that he might come to the cottage that night.

As Walt and I walked away from the story meeting that day he seemed relieved that at last the Sleeping Beauty picture was going to get underway. “I want a moving illustration,” he said. I felt his sincerity. To me his words summed it all up: to Walt nothing was impossible.

Continued in "50 Years in the Mouse House"!

Eric Larson's protege at Disney, Dan Jeup, now an animator for LucasFilm, shares the story of his first meeting with Larson:

My schooling at CalArts began in September 1981. I was seventeen, and soon I would finally meet Eric Larson in person. I didn’t own a car and couldn’t afford one, so thankfully, my brilliantly talented friend and fellow classmate Tim Hauser drove me from Valencia to Burbank in his VW Bug. As Tim sputtered away in his Beetle, I nervously entered the front office located at the studio entrance. With butterflies in my stomach, my eyes scanned a huge mural of Disney characters parading on a wall, which led to a softly lit portrait of Walt Disney smiling back at me. My heart was pounding out of my chest; I couldn’t believe I was actually at the Disney Studio. As I sat there nervously drumming my hands, a young man entered the building. With his back facing me, he spoke with the receptionist and then sat down next to me. That’s funny, I thought, that guy looks just like Peter Brady from The Brady Bunch. Trying not to stare, I slowly turned to sneak a peek at him. Sure enough, it was actor Christopher Knight. It turned out the front office also served as central casting for Disney live-action productions. “Peter Brady” was auditioning for a movie role. I thought seeing my first celebrity was pretty exciting, considering I’d only been in California for a few weeks. Granted, it wasn’t Marlon Brando, but hey, it was still cool to a kid who had just arrived from Michigan.

I was abruptly snapped out of my star-struck stupor when the receptionist informed me I could proceed to Eric’s office. She handed me a visitor’s pass with Mickey Mouse’s face on it. My name appeared below, authorizing me to meet the legendary animator at his office in room 2A-6. On the flipside was a map of the studio along with the Cheshire Cat flashing his crazy smile and his fingers pointing in all directions.

After navigating my way past the orchestra stage and café, I took a right turn at the corner of Mickey Avenue and Dopey Drive, and arrived at the Animation Building, boldly marked with huge art deco letters above the door. I entered its hallowed halls, decorated with stunning artwork from the classic animated films, then anxiously made my way upstairs. I was sweating and my knees were knocking. I was so nervous, my eyes bugged out like Don Knotts from The Apple Dumpling Gang. When I reached the second floor, I stopped in front of a large window and stared out toward the theater across the way, then down the street at the bustling backlot in the distance. I felt like I was in a dream. But everything I’d hoped for was really happening. My eyes began to tear up. I couldn’t believe I was actually at the Disney Studio where all these amazing movies were made! I quickly regained my composure, took a deep breath, and marched into the wing where Eric’s office was located.

His secretary, who was seated in an open area between two adjacent offices, greeted me warmly and then led me into Eric’s spacious office. Eric was a portly, white-haired gentleman, wearing slacks hiked high upon his belly; he shook my hand and welcomed me inside. His low-pitched voice sounded a little like Droopy (Tex Avery’s cartoon dog) though very well spoken and polite. I took a seat in one of the airline chairs facing his impressive director table, then glanced at his animation desk parked next to it, all of which were beautifully designed by architect Kem Weber. The respectable, grandfatherly-like man settled into a chair behind his huge desk, cluttered with notes, drawings, and books. A caricature of Larson by Ward Kimball, a cartoon maquette of story man Joe Ranft, and a portrait of Walt Disney lined the shelf behind him. Eric’s hands tapped a drumbeat on his armchair as he sized me up. Soon, the awkward silence was broken and we began to get acquainted.

Not long into the conversation, the master was eager to teach me a few lessons in action analysis. He demonstrated the basic principles of how to animate a “walk”, miming and breaking down each foot position to be aware of: the “reach”, “contact”, and “push off”. He then talked about the importance of knowing where the force of an action derives from and proceeded to point with his finger, noting that the force of motion starts not at the wrist, but at the shoulder—the whole arm is involved. Later, he showed me a book of action analysis studies of a Dalmatian by animator Marc Davis for the movie 101 Dalmatians and told of the importance of studying how things move.

We admired a model sheet of the character Medusa from The Rescuers and discussed Milt Kahl’s brilliant animation on the villainess. Eric shared a funny story about his hot-tempered colleague, whom Larson regarded as Disney’s best animator. During the making of Bambi, fellow animator and animal expert Ken Hultgren criticized Milt’s drawing of the Stag, claiming he’d drawn the deer’s hind legs incorrectly. Hultgren proceeded to fix the “error”, sketching over Kahl’s drawing. But this was too much for Milt’s huge ego. How dare anyone “correct” Disney’s top animator? Insulted, Kahl went ballistic and kicked Hultgren out of his room, cursing him on his way out!

After laughing over this, Eric led me to his Moviola and ran a student film made by former CalArts alumni and Disney animator Brad Bird (who would later direct The Iron Giant, The Incredibles, and Ratatouille). It was a funny cartoon that featured a wildly enthusiastic used car salesman. The animation was very good and was influenced by Milt Kahl’s work, which was no surprise since Milt had mentored Brad. Eric showed this as an example of a successful student film because the character had a clearly defined personality and was entertaining. No doubt, Bird’s short was impressive and inspiring.

We broke for lunch and drove off the lot to Alphonse’s Restaurant in Toluca Lake, a favorite Disney hangout. Seated at Eric’s “regular booth”, Larson ordered a glass of sherry and some fruit blintzes. When it arrived, I thought it was a little weird. I thought, hmm…I guess he’s skipping lunch and going straight for the dessert. (Incidentally, whenever we had lunch together, he always ordered the same thing. Maybe once he mixed it up with a tuna melt. It was a funny thing because I never saw him eat anything else!) Munching on a cheeseburger, I sat spellbound as Eric reminisced on Disney’s past, telling one great story after the next.

Continued in "50 Years in the Mouse House"!

A young Dan Jeup meets Eric Larson for the first time. (Caricature by Dan Jeup.)

About Theme Park Press

Theme Park Press is the world's leading independent publisher of books about the Disney company, its history, its films and animation, and its theme parks. We make the happiest books on earth!

Our catalog includes guidebooks, memoirs, fiction, popular history, scholarly works, family favorites, and many other titles written by Disney Legends, Disney animators and artists, Mouseketeers, Cast Members, historians, academics, executives, prominent bloggers, and talented first-time authors.

We love chatting about what we do: drop us a line, any time.

Theme Park Press Books

The Unauthorized Story of Walt Disney's Haunted Mansion The Ride Delegate 501 Ways to Make the Most of Your Walt Disney World Vacation The Cotton Candy Road Trip The Wonderful World of Customer Service at Disney Disney Destinies Disney Melodies The Happiest Workplace on Earth Storm over the Bay A Historical Tour of Walt Disney World: Volume 1 Mouse in Transition Mouseketeers Down Under Murder in the Magic Kingdom Walt Disney and the Promise of Progress City Service with Character Son of Faster Cheaper A Tale of Two Resorts I Saw Ariel Do a Keg Stand The Adventures of Young Walt Disney Death in the Tragic Kingdom Two Girls and a Mouse Tale Ears & Bubbles The Easy Guide 2015 Who's the Leader of the Club? Disney's Hollywood Studios Funny Animals Life in the Mouse House The Book of Mouse Disney's Grand Tour The Accidental Mouseketeer The Vault of Walt: Volume 1 The Vault of Walt: Volume 2 The Vault of Walt: Volume 3 Who's Afraid of the Song of the South? Amber Earns Her Ears Ema Earns Her Ears Sara Earns Her Ears Katie Earns Her Ears Brittany Earns Her Ears Walt's People: Volume 1 Walt's People: Volume 2 Walt's People: Volume 13 Walt's People: Volume 14 Walt's People: Volume 15

Write for Theme Park Press

We're always in the market for new authors with great ideas. Or great authors with new ideas. Whichever type of author you are, we'd be happy to discuss your book. Before you contact us, however, please make sure you can answer "yes" to these threshold questions:

Is It Right for Us?

We specialize in books that have some connection to Disney or theme parks. Disney, of course, has become a broad topic, and encompasses not just theme parks and films but comic books, animation, and a big chunk of pop culture. Your book should fit into one (or more) of those broad categories.

Is It Going to Make Money?

There's never a guarantee that any book will make money, but certain types of books are less likely to do so than others. They include: hardcovers, books with color photos, and books that go on forever ("forever" as in 400+ pages). We won't automatically turn down these types of books, but you'll have to be a really good salesman to convince us.

Are You Great to Work With?

Writing books and publishing books should be fun. The last thing you want, and the last thing we want, is a contentious relationship. We work with authors who share our philosophy of no drama and zero attitude, and the desire for a respectful, realistic, mutually beneficial partnership.

If you said "yes" three times, please step inside.