- Visit the Imagineering Graveyard

- Now Sailing: "Skipper Stories" - Tales from the Jungle Cruise

- Coming Soon: The biography of Disney animator Jack Hannah

- Coming Soon: A Haunted Mansion anthology

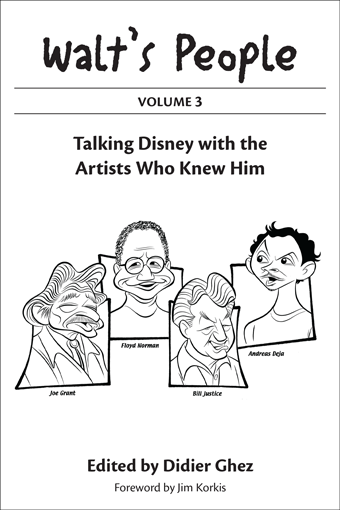

Walt's People: Volume 3

Talking Disney with the Artists Who Knew Him

by Didier Ghez | Release Date: June 24, 2015 | Availability: Print, Kindle

Disney History from the Source

The Walt's People series is an oral history of all things Disney, as told by the artists, animators, designers, engineers, and executives who made it happen, from the 1920s through the present.

Walt’s People: Volume 3 features appearances by Ben Sharpsteen, Ward Kimball, Art Babbitt, Joe Grant, Bill Justice, Volus Jones, Bill Peet, Lee Blair, James Algar, Jack Bradbury, Tony Strobl, Floyd Norman, Burny Mattinson, Phil Nibbelink, and Andreas Deja.

Among the hundreds of stories in this volume:

- BEN SHARPSTEEN recalls the politics of the early Disney Studio, how Walt balanced the creative side of the company against management, and why Mickey Mouse wasn't made for the long haul.

- ART BABBITT provides insight into the Disney Studio strike of 1941 that he instigated, a near fistfight with Walt Disney, and how the aftermath of the strike had a profound effect on the remainder of his career.

- BILL PEET takes no prisoners in his shockingly candid diatribe about his political battles at the Disney Studio, and how he found his greatest success after Disney, as a best-selling author.

- FLOYD NORMAN talks about his awestruck first meeting with Walt as a "kid animator", addresses racism at the Disney Studio, and discusses his work on The Jungle Book and other Disney feature films.

The entertaining, informative stories in every volume of Walt's People will please both Disney scholars and eager fans alike.

Table of Contents

Foreword

Introduction

Ben Sharpsteen by Dave Smith

Ward Kimball by Thorkil B. Rasmussen

Ward Kimball by Klaus Strzyz

Art Babbitt by Klaus Strzyz

Art Babbitt by Michael Barrier

Joe Grant by Michael Lyons

Bill Justice by Jim Korkis

Volus Jones by Wes Sullivan

Bill Peet by John Province

Lee Blair by Robin Allan

James Algar by Robin Allan and Dr. Bill Moritz

Jack Bradbury by Klaus Strzyz

Tony Strobl by Klaus Strzyz

Floyd Norman by Celbi Vagner Pegoraro

Burny Mattinson by Christian Renaut

Andreas Deja by Christian Renaut

Andreas Deja by Didier Ghez

Andreas Deja by Christian Ziebarth

Further Reading

About the Authors

Foreword

Oral history is not for sissies. It is very, very hard work.

A friend recently chided me that it must be the easiest job in the world to listen to some old guy ramble on about his life, transcribe the tape, send it off to a magazine, and wait to collect a fat check. There are so many things wrong with that one sentence it is difficult to know where to begin.

In the first place, some Disney Legends don’t want to be interviewed at all for a variety of reasons, and it takes patience and persistence to persuade them to change their minds. For most of us, it is difficult to remember what we had for lunch last Tuesday, and yet here is an interviewer asking someone to remember with clarity and accuracy what they were thinking, seeing, and doing forty or fifty or more years ago.

A good interviewer comes prepared with research to help prompt those memories, from pictures to filmographies to the actual animated cartoons. Often, it is a good idea to have the spouse there as well since she often corrects statements or provides other avenues of discussion. Other times, having the spouse there can lead to arguments and laconic responses.

A good interviewer has a set of prepared questions, but must also take advantage of the situation when the interviewee goes off on an unexpected tangent, even if it means some of his questions might not get answered.

Anyone who has transcribed an interview will shudder at the tedious and time-consuming work of playing back short sections of conversation over and over and over to get the words just right, or trying to decipher words that are now muffled, or struggling over identifying people vaguely alluded to during the conversation. Then, while transcribing, there is the decision whether to eliminate incomplete sentences and thoughts or correct dates that were misremembered, or whether the subject should be given the chance to review the final copy even if it means they will want to eliminate some of the juiciest stories.

Then, sadly, there really is no market for the interview to be printed, unless it is heavily edited by someone with no understanding of Disney and a lack of interest in some of the more esoteric details.

The interviews showcased in these volumes have been conducted by historians who have done their homework and know what questions to ask and how to guide an interviewee to reveal long-forgotten information or to sidestep the standard pre-prepared story about a particular topic.

Oral history is tremendously valuable since it captures the memories and perspectives of those who were actually there during those magic days at Disney. Unfortunately, too many of the people showcased in these volumes are no longer with us, and these interviews are their only opportunity to share with future historians and fans the true stories and legends behind the magic.

These interviews are gifts to those of us who study and write about Disney history. It is thanks to the patience, hard work, enthusiasm, and persistence of Didier Ghez that these gifts are available to a wide audience and will be available to future researchers to help with their oral histories.

Introduction

I opened the first volume of Walt’s People with the plea: “Re-animate Disney history: unlock the vaults!” I am happy to say that since then the Disney history situation has improved substantially, though we played but a small part in this revival. The E-Ticket magazine has resumed publication, Clay Kaytis has launched the Animation Podcast website, Stephen Worth has started ASIFA’s Virtual Archive project, Kathy Merlock Jackson has edited a collection of interviews with Walt Disney for University of Mississippi Press, and Adrienne Tytla has finally released the long-awaited biography of her husband Bill Tytla. In other words, if Persistence of Vision would only resume publication, and if Disney historians were allowed to get access to Ward Kimball’s famous diaries, we would be in Disney history heaven.

We are not there yet, so let’s carry on our efforts to stimulate Disney history by offering you even more exciting interviews than in earlier volumes of Walt’s People.

There are a few key subjects explored in more detail in this specific volume. By looking at the table of contents, you will have noticed that this book contains two interviews with Art Babbitt, and so you already know that one of those key subjects is the 1941 Studio strike, as seen through the eyes of the strike catalyst. But we also feature a non-striker, Ward Kimball, who gives us, as ever, his own particular version of Disney history.

While reading Ward Kimball’s and Art Babbitt’s testimonies, it is more important than ever to always keep in mind that no statement from any interview should ever be considered as the absolute truth, as the interviewee might have misremembered the facts, may have seen only part of the events described, or may have his own personal reasons for representing reality in a certain way.

Bill Justice and Volus Jones take us back to the world of the Donald Duck shorts that we already explored in detail once through the eyes of Jack Hannah, in Walt’s People: Volume 1.

The Bradbury and Strobl interviews are forays into the world of Disney comics that we had glimpsed through the Gottfredson interview in Walt’s Peole: Volume 2. We will often return to this in the future thanks to famous comics historians like Donald Ault and Alberto Becattini.

Finally, we always try to find the right balance between lesser-known artists like Volus Jones and more-famous ones like Bill Peet and Lee Blair. Likewise, we also believe it is important to include in each volume a few artists who represent the second and third generation of Walt’s people: great artists like Floyd Norman, who worked at the Studio while Walt was still there but did not interact very much with him, and Andreas Deja, who joined after Walt’s death but was trained and tremendously influenced by artists who were part of Walt’s inner circle. These interviews with Norman and Deja also give us the opportunity to welcome Celbi Pegoraro and Christian Ziebarth to the team of Walt’s People contributors.

Talking of new contributors to the series, I have saved the best part for last, as I am happy to announce that Disney archivist Dave Smith has accepted my invitation to contribute to Walt’s People. His interview with Walt’s right hand, Ben Sharpsteen, is considered by many Disney historians as a classic, as it gives key insight into the workings of the Disney Studio in the Hyperion days.

Don’t believe me? Then let’s meet a very unassuming artist…

Didier Ghez

Didier Ghez has conducted Disney research since he was a teenager in the mid-1980s. His articles about the Disney parks, Disney animation, and vintage international Disneyana, as well as his many interviews with Disney artists, have appeared in Animation Journal, Animation Magazine, Disney Twenty-Three, Persistence of Vision, StoryboarD, and Tomart’s Disneyana Update. He is the co-author of Disneyland Paris: From Sketch to Reality, runs the Disney History blog, the Disney Books Network, and serves as managing editor of the Walt’s People book series.

A Chat with Didier Ghez

If you have a question for Didier that you would like to see answered here, please get in touch and let us know what's on your mind.

About The Walt's People Series

How did you get the idea for the Walt's People series?

GHEZ: The Walt’s People project was born out of an email conversation I conducted with Disney historian Jim Korkis in 2004. The Disney history magazine Persistence of Vision had not been published for years, The “E” Ticket magazine’s future was uncertain, and, of course, the grandfather of them all, Funnyworld, had passed away 20 years ago. As a result, access to serious Disney history was becoming harder that it had ever been.

The most frustrating part of this situation was that both Jim and I knew huge amounts of amazing material was sleeping in the cabinets of serious Disney historians, unavailable to others because no one would publish it. Some would surface from time to time in a book released by Disney Editions, some in a fanzine or on a website, but this seemed to happen less and less often. And what did surface was only the tip of the iceberg: Paul F. Anderson alone conducted more than 250 interviews over the years with Disney artists, most of whom are no longer with us today.

Jim had conceived the idea of a book originally called Talking Disney that would collect his best interviews with Disney artists. He suggested this to several publishers, but they all turned him down. They thought the potential market too small.

Jim’s idea, however, awakened long forgotten dreams, dreams that I had of becoming a publisher of Disney history books. By doing some research on the web I realized that new "print-on-demand" technology now allowed these dreams to become reality. This is how the project started.

Twelve volumes of Walt's People later, I decided to switch from print-on-demand to an established publisher, Theme Park Press, and am happy to say that Theme Park Press will soon re-release the earlier volumes, removing the few typos that they contain and improving the overall layout of the series.

How do you locate and acquire the interviews and articles?

To locate them, I usually check carefully the footnotes as well as the acknowledgments in other Disney history books, then get in touch with their authors. Also, I stay in touch with a network of Disney historians and researchers, and so I become aware of newly found documents, such as lost autobiographies, correspondence with Disney artists, and so forth, as soon as they've been discovered.

Were any of them difficult to obtain? Anecdotes about the process?

Yes, some interviews and autobiographical documents are extremely difficult to obtain. Many are only available on tapes and have to be transcribed (thanks to a network of volunteers without whom Walt’s People would not exist), which is a long and painstaking process. Some, like the seminal interview with Disney comic artist Paul Murry, took me years to obtain because even person who had originally conducted the interview could not find the tapes. But I am patient and persistent, and if there is a way to get the interview, I will try to get it, even if it takes years to do so.

One funny anecdote involves the autobiography of the Head of Disney’s Character Merchandising from the '40s to the '70s, O.B. Johnston. Nobody knew that his autobiography existed until I found a reference to an article Johnston had written for a Japanese magazine. The article was in Japanese. I managed to get a copy (which I could not read, of course) but by following the thread, I realized that it was an extract from Johnston’s autobiography, which had been written in English and was preserved by UCLA as part of the Walter Lantz Collection. (Later in his career Johnston had worked with Woody Woodpecker’s creator.) Unfortunately, UCLA did not allow anyone to make copies of the manuscript. By posting a note on the Disney History blog a few weeks later, I was lucky enough to be contacted by a friend of Johnston's family, who lives in England and who had a copy of the manuscript. This document will be included in a book, Roy's People, that will focus on the people who worked for Walt's brother Roy.

How many more volumes do you foresee?

That is a tough question. The more volumes I release, the more I find outstanding interviews that should be made public, not to mention the interviews that I and a few others continue to conduct on an ongoing basis. I will need at least another 15 to 17 volumes to get most of the interviews in print.

About Disney's Grand Tour

You say that you've worked on this book for 25 years. Why so long?

DIDIER: The research took me close to 25 years. The actual writing took two-and-a-half years.

The official history of Disney in Europe seemed to start after World War II. We all knew about the various Disney magazines which existed in the Old World in the '30s, and we knew about the highly-prized, pre-World War II collectibles. That was about it. The rest of the story was not even sketchy: it remained a complete mystery. For a Disney historian born and raised in Paris this was highly unsatisfactory. I wanted to understand much more: How did it all start? Who were the men and women who helped establish and grow Disney's presence in Europe? How many were they? Were there any talented artists among them? And so forth.

I managed to chip away at the brick wall, by learning about the existence of Disney's first representative in Europe, William Banks Levy; by learning the name George Kamen; and by piecing together the story of some of the early Disney licensees. This was still highly unsatisfactory. We had never seen a photo of Bill Levy, there was little that we knew about George Kamen's career, and the overall picture simply was not there.

Then, in July 2011, Diane Disney Miller, Walt Disney's daughter, asked me a seemingly simple question: "Do you know if any photos were taken during the 'League of Nations' event that my father attended during his trip to Paris in 1935?" And the solution to the great Disney European mystery started to unravel. This "simple" question from Diane proved to be anything but. It also allowed me to focus on an event, Walt's visit to Europe in 1935, which gave me the key to the mysteries I had been investigating for twenty-three years. Remarkably, in just two years most of the answers were found.

Will Disney's Grand Tour interest casual Disney fans?

DIDIER: Yes, I believe that casual readers, not just Disney historians, will find it a fun read. The book is heavily illustrated. We travel with Walt and his family. We see what they see and enjoy what they enjoy. And the book is full of quotes from the people who were there: Roy and Edna Disney, of course, but also many of the celebrities and interesting individuals that the Disneys met during the trip. And on top of all of this, there is the historical detective work, that I believe is quite fun: the mysteries explored in the book unravel step by step, and it is often like reading a historical novel mixed with a detective story, although the book is strict non-fiction.

Walt bought hundreds of books in Europe and had them shipped back to the studio library. Were they of any practical use?

DIDIER: Those books provided massive new sources of inspiration to the Story Department. "Some of those little books which I brought back with me from Europe," Walt remarked in a memo dated December 23, 1935, "have very fascinating illustrations of little peoples, bees, and small insects who live in mushrooms, pumpkins, etc. This quaint atmosphere fascinates me."

What other little-known events in Walt's life are ripe for analysis?

DIDIER: There are still a million events in Walt's life and career which need to be explored in detail. To name a few:

- Disney during WWII (Disney historian Paul F. Anderson is working on this)

- Disney and Space (I am hoping to tackle that project very soon)

- The 1941 Disney studio strike

- Walt's later trips to Europe

The list goes on almost forever.

Other Books by Didier Ghez:

- They Drew as They Pleased: The Hidden Art of Disney's Golden Age (2015)

- Disney's Grand Tour: Walt and Roy's European Vacation, Summer 1935 (2013)

- Disneyland Paris: From Sketch to Reality (2002)

Didier Ghez has edited:

- Walt's People: Volume 15 (2014)

- Walt's People: Volume 14 (2014)

- Walt's People: Volume 13 (2013)

- Walt's People: Volume 12 (20xx)

- Walt's People: Volume 11 (20xx)

- Walt's People: Volume 10 (20xx)

- Walt's People: Volume 9 (20xx)

- Walt's People: Volume 8 (20xx)

- Walt's People: Volume 7 (20xx)

- Walt's People: Volume 6 (20xx)

- Walt's People: Volume 5 (20xx)

- Walt's People: Volume 4 (20xx)

- Walt's People: Volume 3 (2015)

- Walt's People: Volume 2 (2015)

- Walt's People: Volume 1 (2014)

- Life in the Mouse House: Memoir of a Disney Story Artist (2014)

- Inside the Whimsy Works: My Life with Walt Disney Productions (2014)

Art Babbitt, once a top animator at Disney's, talks about the studio strike he instigated which led to a lifelong feud with Walt and, arguably, dimmed his career.

Gunther Lessing, who was the vice president and legal counsel for the Disney Studio, called me in one day and said that we should form a union of cartoonists. I was very naïve and I didn’t quite know—I mean, here he was on the management’s side—why should he want a union? What he wanted was a company union that would keep regular unions from getting into the Studio. This is the first time it has ever been mentioned that Gunther Lessing had anything to do with the formation of the union. I’ve spoken of it to people, but this is the first time I’ve put it in recorded form.

So, anyhow, I got the message around the Studio, and very soon I was elected president of this company union. Our attorney at that time was a man by the name of Leonard Janofski, who was at that time legal representative for the Screen Writers Guild. I’m almost certain that this is the same Leonard Janofski who is now head of the American Bar Association. Leonard Janofski said to us, “Look, if you’re going to have a union, you should behave as a union behaves. The idea is to improve the conditions of the people who are represented, financially, safety-wise, medically, and so on.”

We had people at the Studio working for as little as $16 and $18 a week at that time. I happened to be fortunate: at that time my base salary was $200 a week, and stock distribution and bonuses brought my average salary up to $300. In other words, $15,000 a year, which at the height of the Depression was really something. I had two servants, a big house, entertained a lot, I had three cars, which is insanity, you know.

I called for a meeting with Gunther Lessing; Roy Disney, who was business head of the Studio; and Bill Garity, who was the production manager of the Studio, and I proposed that the inkers, who were the lowest paid, be given a two-dollar raise in pay, because even in those days you couldn’t survive on $18 a week. Later that afternoon, Roy Disney called me on the dictagraph—that’s like an intercom now—and said, “You keep your nose out of our business or we’ll cut it off!” I decided then and there that possibly I wasn’t doing the right thing. And mind you, on some of the meetings of the company union Gunther Lessing was present in my house. On one occasion I tried to get my assistant, Bill Hurtz, a raise. He assisted me on Fantasia. Bill Hurtz was a terrific artist, and no matter how bad my art was, he would make it look beautiful. He was getting $25 a week and I was trying to get him $27.50, but no matter how hard I tried, I couldn’t get this raise for him. When I asked for a raise for him, I was told to mind my own business, that if these people were worth it they’d be getting it, and to not care a goddamn about anybody, just worry about my own self. So I finally called Walt Disney and told him what I wanted, and Walt himself said, “Why don’t you mind your own god-damned business, if he was worth it he’d be getting it.” He said, “The trouble with you is that you and your communist friends live in a world so small you don’t know what’s going on around you.” So I said, “Well, if you can’t afford to give it to him, I’ll give him the two-and-a-half dollars a week, because he’s worth it and lots more, and furthermore, I don’t care what you think of my politics as long as you respect my work.” And I said, “If you care to follow me around in the evening you’ll find I still do have a friend or two.” At any rate, to show me that he could afford it, the next morning a whole group of assistants got two-and-a-half-dollar raises.

At that time the Screen Cartoonists Guild had tried to organize the Warner Bros. and MGM Cartoon Departments, and they asked for a meeting with me. They explained what their objectives were, and they asked if I’d join them in making an honest union, one that would really benefit the people we represented, and after thinking it over a few days I agreed to join them. I went about getting people to join the Guild at the Studio, and the way I would do it would be to have meetings in my home. I would have representative people from the Inking Department, for example, come to my house for drinks and a very nice dinner, and then I would give my little talk about unionization and joining this Screen Cartoonists Guild. I did this with all departments. I don’t think any union organization was ever carried on in this manner.

I also recruited on Studio grounds whenever I had the chance, and the Studio warned me not to solicit membership in this union on Studio property at any time. Well, it so happens that we had a law passed in 1936, I believe, called the Wagner Labor Relations Act. Essentially, the law said that no employer could prevent you from soliciting membership in a union. After a considerable amount of time in getting people to join, we had a sizable membership at the Disney Studio. We knew that if we didn’t win recognition at Disney’s, there would be no chance of winning recognition at any of the other studios.

So, the reason for the strike was to get union recognition, because as a group we would have more power to raise salaries and improve conditions. Another big reason for the strike was this: there were two men by the name of Willie Bioff and George Browne who controlled all of the studio unions except the painters, and they were crooks, they were henchmen of Al Capone. Willie Bioff was blown up in his car; his car was dynamited in Arizona or Nevada or someplace about ten or twelve years ago. These two men came out here, and through pressure made arrangements with the various studio heads that they would run the IATSE. The IATSE controlled all the theatrical and motion picture unions at that time, the studio teamsters, the studio carpenters, the studio set builders, the works. We little cartoonists didn’t want gangsters to run our union. It so turns out that the Disney Studio was working very closely with Willie Bioff and George Browne.

I was harassed for months before the strike by studio management, and told to cut out my union activities or else. Of course, I refused to acquiesce to that, and I went on just as I had before because I knew I had the law on my side. One day, to my surprise, I guess, two detectives from the Burbank police station appeared in my office and arrested me, and the charge against me was carrying a concealed weapon. My weapon was so concealed that to this day they have not found it. I was taken to the Burbank jail. Now there were just a few coincidences that day. One was that at 2:00 that afternoon I was scheduled to go to the National Labor Relations Board to give my deposition about why we wanted recognition, and how the Studio was thwarting us. The other coincidence was that the chief of police of Burbank was the brother-in-law of the chief of studio security at Disney’s. That’s just a coincidence. The detectives picked me up at noon, took my fingerprints, the whole bit, and put me in the Burbank jail. I wasn’t allowed to make any phone calls. I was put into a big cell which is called a cooler, where they put drunks, pimps, dope peddlers, and so on, and it was below street level. One tiny window. Near that little window a young boy, maybe 10, 12, would come by selling apples and cigarettes and things like that. Everything was taken from me when I was put in this little room, but one of the pimps had some money, and he bought apples and cigarettes for all of us, which made me think that, possibly, they had the wrong people in jail and the wrong people outside of jail. At any rate, the girl who was assistant chairman of the Disney unit of the Guild—I was the chairman—called the various jails, figuring I had to be in jail someplace, and finally she found out where I was in Burbank. All of a sudden, I was released and taken to Disney’s office, and Disney again gave me a fatherly lecture to the effect that if I lived right and thought right everything would be marvelous.

I guess I didn’t live right. A few weeks later, about lunch time, two Studio policemen came to get me. They handed me a very foolishly and stupidly written letter by this Gunther Lessing. The essence of it was that since they had repeatedly warned me to not do any unionization efforts or something like that at the Studio and I hadn’t obeyed them, I was being fired. No warning or anything like that. It so happens that I had a three-year contract with two more years to go, I had work in progress, but they fired me. So I said, “Alright, I’ve been here for many years, do you mind if I go get my pencils and things?” Well, it took me half an hour to get my pencils, and by that time quite a crowd had collected. The two policemen marched me out of the Studio gate, and there was quite a bit of commotion caused by the people who had witnessed this.

Continued in "Walt's People: Volume 3"!

Teenaged Floyd Norman (now a Disney Legend who celebrated his 80th birthday in 2015) recalls his first encounter with Walt Disney.

Well, I didn’t really meet Walt Disney the first time I saw him.

It was my first week at the Disney Studio as a young animation trainee. Seven of us were in an animation class trying to qualify as Disney animation artists. We were going through drawing exercises and classes.

One day we were told to report to the screening room up on the third floor of the Animation Building. While we waited in the hallway, we heard the elevator doors open at the far end of the hallway, and a shadowy figure emerged from the elevator. The figure moved slowly toward us backlit by the large window at the south side of the hall. Suddenly, we realized the man coming toward us was none other than Walt Disney. Backlit by the window, Walt seemed to be a vision. Like Moses coming down from the mount. All of us kids backed against the wall as Walt Disney walked past. He had a smile on his face because I’m sure he was amused by our silly behavior.

At this time in my career, I was just a kid who was afraid to talk to animators, much less Walt Disney. In time, I grew more confident, and got to know many of the Disney animators, and even some musicians and actors who worked at the Studio. Walt Disney spent most of his time with the story artists upstairs, and was rarely seen in the animation halls on the first floor. He would watch the films in “sweat box” sessions on the second floor, but none of us newcomers were invited to such meetings with the boss.

Still, Walt Disney was a friendly gentleman, and he would always speak to us as he walked past on the Studio lot. A conversation with Walt was reserved for the senior members of his team, or high-level employees. I never dared to even talk to Walt unless he spoke first. One day, one of my animation pals had a visitor from Africa. This little lady was a missionary, and had just seen Walt Disney’s The African Lion. We happened to see Walt strolling on the back lot, and my friend introduced Walt to the missionary. Walt was very proud of his new movie, but the missionary said the film was not all that accurate when it came to portraying African lions. Walt insisted the film was correct, and the missionary insisted it was not. This was one conversation with Walt Disney that turned out to be a very bad idea.

As time went on, Walt seemed to recognize me. He never called me by name, but often said, “Hiya, kid!” as he walked passed me in the hallway or on the Studio lot. I was pleased to be called “kid” because at least the boss seemed to know who I was. As I moved up the ranks, I was able to attend meetings and screenings with Disney. This was great, because I was able to hear from the boss himself. I got to know first-hand what he really liked or didn’t like and why. I think I learned a great deal, not so much by talking to Walt Disney, but by listening to him. Of course, I was just a kid, and really didn’t have anything to contribute. I was at the Disney Studio to learn, not to talk. One day, I did have a brief conversation with Walt Disney as he walked to his office. It was on a narrow walkway between the theater and the recording stage. After Disney went on his way, I kept thinking to myself, “Gee, Walt Disney actually talked to me!” That was many years ago, but I’ll never forget that day as long as I live.

Continued in "Walt's People: Volume 3"!

About Theme Park Press

Theme Park Press is the world's leading independent publisher of books about the Disney company, its history, its films and animation, and its theme parks. We make the happiest books on earth!

Our catalog includes guidebooks, memoirs, fiction, popular history, scholarly works, family favorites, and many other titles written by Disney Legends, Disney animators and artists, Mouseketeers, Cast Members, historians, academics, executives, prominent bloggers, and talented first-time authors.

We love chatting about what we do: drop us a line, any time.

Theme Park Press Books

The Unauthorized Story of Walt Disney's Haunted Mansion The Ride Delegate 501 Ways to Make the Most of Your Walt Disney World Vacation The Cotton Candy Road Trip The Wonderful World of Customer Service at Disney Disney Destinies Disney Melodies The Happiest Workplace on Earth Storm over the Bay A Historical Tour of Walt Disney World: Volume 1 Mouse in Transition Mouseketeers Down Under Murder in the Magic Kingdom Walt Disney and the Promise of Progress City Service with Character Son of Faster Cheaper A Tale of Two Resorts I Saw Ariel Do a Keg Stand The Adventures of Young Walt Disney Death in the Tragic Kingdom Two Girls and a Mouse Tale Ears & Bubbles The Easy Guide 2015 Who's the Leader of the Club? Disney's Hollywood Studios Funny Animals Life in the Mouse House The Book of Mouse Disney's Grand Tour The Accidental Mouseketeer The Vault of Walt: Volume 1 The Vault of Walt: Volume 2 The Vault of Walt: Volume 3 Who's Afraid of the Song of the South? Amber Earns Her Ears Ema Earns Her Ears Sara Earns Her Ears Katie Earns Her Ears Brittany Earns Her Ears Walt's People: Volume 1 Walt's People: Volume 2 Walt's People: Volume 13 Walt's People: Volume 14 Walt's People: Volume 15

Write for Theme Park Press

We're always in the market for new authors with great ideas. Or great authors with new ideas. Whichever type of author you are, we'd be happy to discuss your book. Before you contact us, however, please make sure you can answer "yes" to these threshold questions:

Is It Right for Us?

We specialize in books that have some connection to Disney or theme parks. Disney, of course, has become a broad topic, and encompasses not just theme parks and films but comic books, animation, and a big chunk of pop culture. Your book should fit into one (or more) of those broad categories.

Is It Going to Make Money?

There's never a guarantee that any book will make money, but certain types of books are less likely to do so than others. They include: hardcovers, books with color photos, and books that go on forever ("forever" as in 400+ pages). We won't automatically turn down these types of books, but you'll have to be a really good salesman to convince us.

Are You Great to Work With?

Writing books and publishing books should be fun. The last thing you want, and the last thing we want, is a contentious relationship. We work with authors who share our philosophy of no drama and zero attitude, and the desire for a respectful, realistic, mutually beneficial partnership.

If you said "yes" three times, please step inside.