- Visit the Imagineering Graveyard

- Now Sailing: "Skipper Stories" - Tales from the Jungle Cruise

- Coming Soon: The biography of Disney animator Jack Hannah

- Coming Soon: A Haunted Mansion anthology

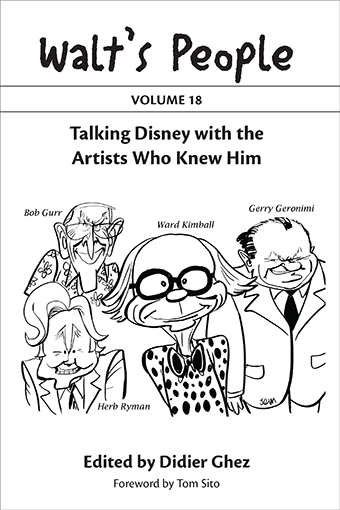

Walt's People: Volume 18

Talking Disney with the Artists Who Knew Him

by Didier Ghez | Release Date: June 6, 2016 | Availability: Print, Kindle

Disney History from the Source

The Walt's People series is an oral history of all things Disney, as told by the artists, animators, designers, engineers, and executives who made it happen, from the 1920s through the present.

Walt's People: Volume 18 features appearances by Mique Nelson, Katherine Kerwin, Gerry Geronimi, Ward Kimball, Dick Huemer, Ken O'Connor, Janet Martin, Herb Ryman, Don Douglass, Ken Peterson, Kay Wright, Del Connell, Elma Milotte, Bob Gurr, Barbara Palmer, and Hani El-Masri.

Among the hundreds of stories in this volume:

- HANI EL-MASRI recounts his fascinating journey from the streets of Cairo, Egypt, to Disney Imagineering.

- GERRY GERONIMI, perhaps the least-liked person ever to work at the Disney Studio, tells his side of the story about his feud with Ward Kimball, his firing by Walt Disney, and other incidents.

- BOB GURR tells the tale of horror that was Autopia on Disneyland's opening day in 1955.

- ELMA MILOTTE shares her and her husband Al's thrilling exploits across the world as the photographers for Disney's True-Life Adventure series.

The entertaining, informative stories in every volume of Walt's People will please both Disney scholars and eager fans alike.

Table of Contents

Foreword

Introduction

Mique Nelson

Katherine Kerwin by Dave Smith

Gerry Geronimi by Michael Barrier and Milton Gray

Gerry Geronimi by Ross Care

Ward Kimball by Ross Care

Ward Kimball by John Culhane

Dick Huemer by John Culhane

Ken O'Connor by Ron Merk

Chaperone for Donald Duck by Janet Martin

Herb Ryman by Katherine and Richard Greene

Five Years with Walt by Don Douglass

Ken Peterson by Bob Thomas

Ken Peterson by Bob Thomas

Kay Wright by Alberto Becattini

Del Connell by Bill Spicer

Elma Milotte by MICO Productions

Bob Gurr by Doobie Moseley

Bob Gurr by Jim Korkis

Bob Gurr by Didier Ghez

Barbara Palmer by Michael Broggie

Hani El-Masri by Julie Svendsen

Further Reading

About the Authors

Foreword

I am a Disney animator. I have not worked for the studio in over twenty years. But that does not matter. In my forty-year career I have worked for Warner Bros., Hanna & Barbera, Filmation, and a dozen other studios around the globe. But that does not matter. To the public who still loves Roger and Jessica, Ariel and Simba, I will always be a Disney animator.

I first observed this phenomenon in 1977 in New York when I became the assistant to James “Shamus” Culhane on his final film. We were working on a low-budget educational film. Shamus had animated for J.R. Bray, Max Fleischer, Walter Lantz, and Leon Schlesinger, animated Saul Bass’ title designs for Mike Todd’s Around the World in Eighty Days, and created some of the earliest animated television commercials. He had been married to the daughter of Chico Marx and lived with the Marx Brothers. But what he was really known for was his work at Walt Disney. He was a Pluto animator under Norm Ferguson, on shorts like Hawaiian Holiday. He animated several scenes in the Heigh-Ho, Heigh Ho march in Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, and he did some early scenes of Honest John and the Coachman in Pinocchio. No matter what he did for the rest of his life, those films were part of his reputation. Richard Williams called credits like that your armor.

Shamus was proud of his years at Disney. He said he owed a lot to the training he got there. The art lessons from Don Graham. The screenings and lectures. The insistence on getting it right over doing it cheaply or quickly. That Walt brought in people like Frank Lloyd Wright and Sergei Eisenstein to debate aesthetics. “You don’t understand, at Fleischer we were only doing formula gags,” he’d say to me. “Walt Disney was really DOING it! Pure personality work!” He said by the late 1930s Disney was the studio leading the entire field of animation. Shamus really admired Walt Disney the man, even though he admitted Walt Disney could be a hard boss at times, and a mean SOB, if you ever crossed him.

Shamus Culhane was the first of the tribe of Golden Age Walt Disney artists who I got to know well. In the coming decades I befriended many more: Marc Davis, Alice Davis, Frank Thomas, Ollie Johnston, Joe Grant, Maurice Noble, Art Babbitt, Grim Natwick, Ward Kimball, Dave Hilberman, Jules Engel, Kendal O’Connor, Vance Gerry, Stan Green, Dale Oliver, Corny Cole, Floyd Norman, Bud Hester, Charlie Downs, Charles “Nick” Nichols, Bill Melendez, Ed Fourcher, Hicks Lokey, and Roy E. Disney.

I knew a lot of other artists from the other studios, but there was something special about being Disney. Their fierce loyalty to Walt’s memory. “The difference between you and me,” Joe Grant once said to me, “is you work for Disney’s, while I work for WALT Disney.” Even artists who felt unjustly treated by Walt, like Babbitt, still maintained a glowing respect for the man. The halls of the studio still echoed with his presence. So much so, that twenty years after his death, people in meetings would still say, “Whattaya think Walt would say?”

Many people talk about the Walt Disney Studio, but once you were an animator inside its walls, you were accepted. You were one of them. And we animators enjoyed a special status as cardinals of the church. When the Nine Old Men were named in 1949, they were all character animators—something pointed out to me with great annoyance by their peers from the other departments. When you became part of the fraternity, the older animators who would speak to the public with a gentle “aw-shucks” humility would suddenly come clean to you. “Geez, never liked C … , I’m sure glad he’s dead,” etc. I once asked Joe Grant, “What is the main difference between the animators now and the animators of 1940?” He replied, “Aw … same old pressures, same politics, same deadlines … people drew better back then.”

The work environment of the animation studios of the early twentieth century had evolved out of the newspaper business. As children, many Disney animators had originally dreamt of being comic-strip artists in one of the big city papers. They became animators almost as a fall-back job. Some indeed moved on to fame in print like Walt Kelly, George Baker, and Fleischer assistant animator Jacob Kurtzberg, who changed his name to Jack Kirby. Those that remained modeled their workspace after a newspaper bullpen. They referred to animation as “the racket”. A hard-drinking, cigar-chomping, spittoon-spitting, profane bunch. In the early silent movie days, studio heads like Bud Fisher of Mutt & Jeff and Pat Sullivan of Felix the Cat were known to waste much of their studios’ profits on bootleg gin, and Ziegfeld Follies chorus girls. Walt Disney decided to change this image of what a studio was, starting with himself.

As young artist Walt Disney matured, he developed an image of the kindly, squeaky-clean Uncle Walt, welcome in every family’s home. He was very careful in its creation. The real Walt chain-smoked Marlboros and enjoyed his after-work cocktail, often brought to him by the studio nurse on a dish. He could resort to profanity when it suited him “It’s MY goddamn studio, so we’ll do it my way!” But this Walt was carefully hidden from the general public. What everyone saw in interviews, magazines, and TV was this genial, modest figurehead with the warm smile and soft voice. Anecdotes began to ciruclate of Walt firing a story artist for using too much profanity in his pitches, and firing one guy for telling a dirty joke. The guy wasn’t even saying it to Walt. Walt just happened to overhear it as he walked past.

This ideal filtered down to his artists. From early on, Walt encouraged his people to think they were separate and apart from the rest of the animation business, that they were special, the elite. Many of them prized their closeness to Walt, and emulated him. One old artist said, “It was the darndest thing. If one day Walt came in wearing a suede jacket, soon everyone was wearing suede jackets!” They followed their leader in adopting this clean-cut, all American image. It suited the temperament of the post-war era: middle age, middle class, middle American.

I always felt the difference between the Golden Age generation and my own Baby Boom generation at Disney was that the old guys were in on this style change from the beginning, while my generation grew up actually believing it. When I first came out from New York, where animation was closely tied to the tough advertising world of Madison Avenue, at first look Walt Disney’s seemed like I was trapped in the world of That Darn Cat or Those Calloways. After the cultural revolutions of the 1960s, Lenny Bruce and Woodstock, people on the Disney lot still used expletives like “Jimminy!” and “Gosh!” The Disney style code was finally relaxed so that women could wear jeans only in 1977!

With the arrogance of youth, at first I viewed this all with disdain. But in retrospect I can appreciate the power of the image’s attraction, watching the reactions of people, especially children, when you say you drew Sebastian or Simba. Disney is more than an image, it’s a way of life. Something positive and good. The innocence and enthusiasm of childhood celebrated. Something timeless. Many today don’t go out of their way to watch a movie from 1937, but you can still enjoy Snow White like the day it first opened. Fox Studios can be iconoclastic, Warner Bros. could be urbane and cynical. But Walt Disney’s cannot go there and still remain Walt Disney.

I am so grateful to Didier Ghez for creating this series of Walt’s People books to permanently preserve the oral histories of all these wonderful animation artists, many of whom are now gone. Hollywood studios nowadays hire and fire on a per-project basis, so there is little opportunity to perfect your technique over a long period. Disney’s studio acted like a repertory company, where the same artists went on from film to film—some like Frank & Ollie for over forty-six years. Their styles of animation were so individual that you could spot them on screen. That looks like a Tytla scene. That looks like a John Sibley. These talented people all came from different backgrounds, and possessed different temperaments and opinions. Yet what they all had in common was this shared understanding of what it took to be a Walt Disney artist. And what Walt Disney, as an ideal, means to the rest of the world.

As a young artist I was in awe of these white-haired gods. Now I am white haired. I have movies to my credit no one can ever take away: Who Framed Roger Rabbit?, The Little Mermaid, Beauty and the Beast, Aladdin, The Lion King, Pocahontas. They are my armor. The stress of the deadlines, money arguments, studio politics have melted away over the years. Now all that remains is the warm glow of their success.

When you become a Disney animator, you feel the weight of the legacy. You see the exquisite drawings of the old masters on the walls. You sit at their old desks and inspect the cigarette burns on the edges of the shelves. You wonder who actually sat at the desk you are now at. You check reference books out of the Disney Research Library and spot who signed them out before you: Marc Davis, Ward Kimball, Albert Hurter. It feels like you’ve been given a priceless antique glass figurine to juggle. And all the while you are juggling it, you are warned that no one has ever dropped it before. Now that I have passed that glass on, I am proud of the part I have played in maintaining and advancing the Walt Disney legacy to a new generation of fans.

Over the years I have had many titles: clean-up artist, director, storyboard artist, author, historian, guild president emeritus, professor and chair of animation for the University of Southern California. But the title I cherish the most, the title I am most proud of, is Walt Disney animator.

Introduction

When I was a kid, I dreamt of building a time machine. I read time-travel novels with fascination. I learned everything there was to learn about the science of time. And I discovered that from a scientific standpoint, time travel would never be a reality.

That’s when I decided to take a different approach. My passion being Disney history, I started looking for diaries, correspondence, and photographs linked to the men and women who had worked for Walt Disney. I discovered more than I expected. In themselves they were small time capsules. Taken as a whole, they acted like time machines.

Over the last few days, I just spent time looking over the shoulder of the Ecuadorian artist Eduardo Solá Franco, thanks to the letters he wrote daily to his family while working for the Disney Studio on the Don Quixote project in 1939. I looked around his office, I shared his joys and frustrations, and I even met his friends. I will share the results of this time-travel experience in the third volume of They Drew As They Pleased, in September 2017.

A few weeks ago, I travelled to Salta, Argentina, with artists James Bodrero, Frank Thomas, and Larry Lansburgh, thanks to the 1941 diary of Lansburgh. Through their eyes I witnessed a barbaric condor hunt and took part in an unforgettable feast at the end of the day, complete with a mouth-watering “asado”.

The perspectives of Lansburgh and Solá Franco, however, are highly subjective ones. They are exhilarating as a time-travel experience, but writing about history involves going one step further and contextualizing them. This truth was particularly obvious in the case of the Solá Franco letters. As you read them, you realize quickly that Solá Franco had no idea of how the Disney Studio operated when it came to corporate power plays and other failings of large corporations. His frustrations were often the result of these deep misunderstandings. As a historian, one has to give the readers the clues which allow them to understand this.

As often stated in the past, the Walt’s People book series does not contextualize much, and should therefore be used not as a history book but as a collection of tools to build future history books. I am giving you the raw material which, later, will need to be put into perspective.

The collection of raw material in this new volume is particularly satisfying, with some of the highlights being the long interview with layout artist Ken O’Connor by Ron Merk, the fascinating interview of director Gerry Geronimi by Michael Barrier, the never-seen-before article by Janet Martin about the 1941 trip to Latin America, and the interview with Elma Milotte, which I had been trying to include in Walt’s People for many years.

But, of course, my favorite piece has to be the first one in the volume, the correspondence of background artist Mique Nelson, since it gives us a sense of immediacy like no other in the book.

And so, without further ado, thanks to Mique Nelson it is time, once more, to board our newly built time machine.

Didier Ghez

Didier Ghez has conducted Disney research since he was a teenager in the mid-1980s. His articles about the Disney parks, Disney animation, and vintage international Disneyana, as well as his many interviews with Disney artists, have appeared in Animation Journal, Animation Magazine, Disney Twenty-Three, Persistence of Vision, StoryboarD, and Tomart’s Disneyana Update. He is the co-author of Disneyland Paris: From Sketch to Reality, runs the Disney History blog, the Disney Books Network, and serves as managing editor of the Walt’s People book series.

A Chat with Didier Ghez

If you have a question for Didier that you would like to see answered here, please get in touch and let us know what's on your mind.

About The Walt's People Series

How did you get the idea for the Walt's People series?

GHEZ: The Walt’s People project was born out of an email conversation I conducted with Disney historian Jim Korkis in 2004. The Disney history magazine Persistence of Vision had not been published for years, The “E” Ticket magazine’s future was uncertain, and, of course, the grandfather of them all, Funnyworld, had passed away 20 years ago. As a result, access to serious Disney history was becoming harder that it had ever been.

The most frustrating part of this situation was that both Jim and I knew huge amounts of amazing material was sleeping in the cabinets of serious Disney historians, unavailable to others because no one would publish it. Some would surface from time to time in a book released by Disney Editions, some in a fanzine or on a website, but this seemed to happen less and less often. And what did surface was only the tip of the iceberg: Paul F. Anderson alone conducted more than 250 interviews over the years with Disney artists, most of whom are no longer with us today.

Jim had conceived the idea of a book originally called Talking Disney that would collect his best interviews with Disney artists. He suggested this to several publishers, but they all turned him down. They thought the potential market too small.

Jim’s idea, however, awakened long forgotten dreams, dreams that I had of becoming a publisher of Disney history books. By doing some research on the web I realized that new "print-on-demand" technology now allowed these dreams to become reality. This is how the project started.

Twelve volumes of Walt's People later, I decided to switch from print-on-demand to an established publisher, Theme Park Press, and am happy to say that Theme Park Press will soon re-release the earlier volumes, removing the few typos that they contain and improving the overall layout of the series.

How do you locate and acquire the interviews and articles?

To locate them, I usually check carefully the footnotes as well as the acknowledgments in other Disney history books, then get in touch with their authors. Also, I stay in touch with a network of Disney historians and researchers, and so I become aware of newly found documents, such as lost autobiographies, correspondence with Disney artists, and so forth, as soon as they've been discovered.

Were any of them difficult to obtain? Anecdotes about the process?

Yes, some interviews and autobiographical documents are extremely difficult to obtain. Many are only available on tapes and have to be transcribed (thanks to a network of volunteers without whom Walt’s People would not exist), which is a long and painstaking process. Some, like the seminal interview with Disney comic artist Paul Murry, took me years to obtain because even person who had originally conducted the interview could not find the tapes. But I am patient and persistent, and if there is a way to get the interview, I will try to get it, even if it takes years to do so.

One funny anecdote involves the autobiography of the Head of Disney’s Character Merchandising from the '40s to the '70s, O.B. Johnston. Nobody knew that his autobiography existed until I found a reference to an article Johnston had written for a Japanese magazine. The article was in Japanese. I managed to get a copy (which I could not read, of course) but by following the thread, I realized that it was an extract from Johnston’s autobiography, which had been written in English and was preserved by UCLA as part of the Walter Lantz Collection. (Later in his career Johnston had worked with Woody Woodpecker’s creator.) Unfortunately, UCLA did not allow anyone to make copies of the manuscript. By posting a note on the Disney History blog a few weeks later, I was lucky enough to be contacted by a friend of Johnston's family, who lives in England and who had a copy of the manuscript. This document will be included in a book, Roy's People, that will focus on the people who worked for Walt's brother Roy.

How many more volumes do you foresee?

That is a tough question. The more volumes I release, the more I find outstanding interviews that should be made public, not to mention the interviews that I and a few others continue to conduct on an ongoing basis. I will need at least another 15 to 17 volumes to get most of the interviews in print.

About Disney's Grand Tour

You say that you've worked on this book for 25 years. Why so long?

DIDIER: The research took me close to 25 years. The actual writing took two-and-a-half years.

The official history of Disney in Europe seemed to start after World War II. We all knew about the various Disney magazines which existed in the Old World in the '30s, and we knew about the highly-prized, pre-World War II collectibles. That was about it. The rest of the story was not even sketchy: it remained a complete mystery. For a Disney historian born and raised in Paris this was highly unsatisfactory. I wanted to understand much more: How did it all start? Who were the men and women who helped establish and grow Disney's presence in Europe? How many were they? Were there any talented artists among them? And so forth.

I managed to chip away at the brick wall, by learning about the existence of Disney's first representative in Europe, William Banks Levy; by learning the name George Kamen; and by piecing together the story of some of the early Disney licensees. This was still highly unsatisfactory. We had never seen a photo of Bill Levy, there was little that we knew about George Kamen's career, and the overall picture simply was not there.

Then, in July 2011, Diane Disney Miller, Walt Disney's daughter, asked me a seemingly simple question: "Do you know if any photos were taken during the 'League of Nations' event that my father attended during his trip to Paris in 1935?" And the solution to the great Disney European mystery started to unravel. This "simple" question from Diane proved to be anything but. It also allowed me to focus on an event, Walt's visit to Europe in 1935, which gave me the key to the mysteries I had been investigating for twenty-three years. Remarkably, in just two years most of the answers were found.

Will Disney's Grand Tour interest casual Disney fans?

DIDIER: Yes, I believe that casual readers, not just Disney historians, will find it a fun read. The book is heavily illustrated. We travel with Walt and his family. We see what they see and enjoy what they enjoy. And the book is full of quotes from the people who were there: Roy and Edna Disney, of course, but also many of the celebrities and interesting individuals that the Disneys met during the trip. And on top of all of this, there is the historical detective work, that I believe is quite fun: the mysteries explored in the book unravel step by step, and it is often like reading a historical novel mixed with a detective story, although the book is strict non-fiction.

Walt bought hundreds of books in Europe and had them shipped back to the studio library. Were they of any practical use?

DIDIER: Those books provided massive new sources of inspiration to the Story Department. "Some of those little books which I brought back with me from Europe," Walt remarked in a memo dated December 23, 1935, "have very fascinating illustrations of little peoples, bees, and small insects who live in mushrooms, pumpkins, etc. This quaint atmosphere fascinates me."

What other little-known events in Walt's life are ripe for analysis?

DIDIER: There are still a million events in Walt's life and career which need to be explored in detail. To name a few:

- Disney during WWII (Disney historian Paul F. Anderson is working on this)

- Disney and Space (I am hoping to tackle that project very soon)

- The 1941 Disney studio strike

- Walt's later trips to Europe

The list goes on almost forever.

Other Books by Didier Ghez:

- They Drew as They Pleased: The Hidden Art of Disney's Golden Age (2015)

- Disney's Grand Tour: Walt and Roy's European Vacation, Summer 1935 (2013)

- Disneyland Paris: From Sketch to Reality (2002)

Didier Ghez has edited:

- Walt's People: Volume 15 (2014)

- Walt's People: Volume 14 (2014)

- Walt's People: Volume 13 (2013)

- Walt's People: Volume 12 (20xx)

- Walt's People: Volume 11 (20xx)

- Walt's People: Volume 10 (20xx)

- Walt's People: Volume 9 (20xx)

- Walt's People: Volume 8 (20xx)

- Walt's People: Volume 7 (20xx)

- Walt's People: Volume 6 (20xx)

- Walt's People: Volume 5 (20xx)

- Walt's People: Volume 4 (20xx)

- Walt's People: Volume 3 (2015)

- Walt's People: Volume 2 (2015)

- Walt's People: Volume 1 (2014)

- Life in the Mouse House: Memoir of a Disney Story Artist (2014)

- Inside the Whimsy Works: My Life with Walt Disney Productions (2014)

Mique Nelson, though little known, nonetheless gives a fascinating account of the early Disney Studio.

Walt works almost entirely now with the story room. Before each picture is started, a gag meeting is held at which the entire animating and production staff submits gags for the picture under discussion. Two fifty is paid for every gag accepted. The Story Department gets these gags to build up.

When the story has been whipped into shape and gagged, it goes to the director who times it, plans the animation and the scenes with his layout men. As soon as this is done, the layout men get active and build up the scenes.

That is wonderfully interesting work. It means roughing out the whole picture in sketches. Every scene is plotted so that the action will be clear and in no way interfered with, and when the mechanical requirements of the scenes have been met, the picture goes to the background artists.

As soon as the picture is plotted by the director and layout men, elaborate production sheets are prepared, each line of which corresponds to a beat of music. The musician who builds the score has arranged his music to fit every scene perfectly, and the drawings are made to synchronize with the music. Every beat has to fit the animation.

An animator works on a drawing board that has a piece of plate glass set in the middle and a light shining thru the glass. There are two metal pegs on his board on which he fits pieces of punched bond paper. He makes his first drawing in a particular scene. Suppose it is a sequence where only the lifting on an arm is involved. To complete that movement normally, sixteen drawings will be required, because the eye has sixteen stopping points in every normal movement. The animator will draw perhaps three of these stopping points—the beginning, the halfway mark, and the end—each on a separate sheet. All sheets are punched alike,—all are placed on the pegs, and so the result will be smooth continuity.

The drawings made, he turns them over to an inbetweener who nearly traces them, supplying the necessary in-between positions. A tedious job. If fast action is required, fewer inbetweens. For slow action, more inbetweens. For very slow, the cameras will shoot each inbetween from two to four times.

Ordinarily we have about an average of 55 scenes to a picture, requiring about 35 separate background paintings. Some of these scenes are very short—one in my last picture was only 2½ seconds in length or 60 frames—less than 4 feet of film. It required the making of a very intricate panorama background which took me two days to paint.

Our average picture takes from ten to fifteen thousand separate animation drawings.

When an animator finishes a scene, all the drawings go to the inkers. At times three or four assistants have been working on one scene and maybe as many as four drawings will have to be assembled to make up the action of each shot on the camera. So the girls assemble all the drawings bearing the same number, put them on their drawing-board pegs, place a sheet of clear celluloid over the whole, and carefully trace the animation in ink on the celluloid, commonly termed a “cel”.

When a scene has been inked it goes to the painters. If it is a Mickey, all the characters are filled in in opaque grays, white, and black. I have previously had to decide on tones of gray for the painting that will contrast strongest with my backgrounds.

As I complete backgrounds, which are simply watercolor paintings, the background and cels are sent to the camera. There the cels are superimposed on the background and shot. Cels are removed and a fresh batch put on and shot and this goes on—four cels at each shot, until a scene is taken in sequence of action. You remember the books of prize fighters and ballplayers that we had when kids—flipped the pages and got action. Well, each assembly of cels over the background is like one page in one of those books. When they are run thru a projector at the rate of 24 frames or pictures per second, we get smooth and continuous action.

If the picture is a Symphony, the cels are painted in brilliant opaque colors instead of the grays. Our shooting then is done at Technicolor. Four negatives are shot—one black, and the others with filters to get the three primaries, red, yellow, and blue. Then, in some secret manner, they actually print their colors from positive prints of the four keys—all printed like process printing on a color press.

I have to draw my backgrounds from the layout designs and then paint them the same as I would paint from nature, except that I have to paint entirely from memory. There is a world of detail to be familiar with regarding the mechanics of animation, registration of characters to my backgrounds, so that when a character is to pass behind a tree, for example, he will pass behind that tree. Fortunately, I got deeply interested in photography about five years ago and have gone pretty far in the art. So I brought more knowledge of the mechanics of the camera to my job than the cameramen at the studio have brought to theirs. When we have to devise tests for definite gammas and so forth in printing, I usually get stuck for the job. But it has helped me go ahead.

Where lateral or horizontal action is required, I paint what we term “pans”. Some of these have reached 24 feet in length. The average is five feet. In pan action not only the animated characters move, but at each shot of the camera the background is moved. For very slow pan movement, we move the background a sixteenth of an inch at a shot. We scale from that up to speed where the pan moves an inch at a shot.

Before the picture is entirely shot, the sound and dialogue are recorded. I think you know the process. The sound is actually photographed and shot on film and the image of the soundwaves is transposed back into sound when projected with the picture. The musicians all wear earphones and get their beat from the film running thru the sound truck, so they are in perfect “sync” with the animation. We dub now in French and Spanish dialogue.

Now the preview. Usually at a Hollywood house. There we get the reaction of the audience. For ourselves, we have run the damned picture a hundred times on our small Moviola projector in the sweatbox. Every day the animators make test drawings and we project the negatives and criticize. As scenes are shot, the daily rushes come back from the lab and we run and criticize them: animation, painting, backgrounds.

If something is sour at a preview, the offending department or persons are given a luncheon in the studio dining room the following day. Ann serves a lovely meal, the studio pays for it, but nobody but Walt enjoys it. Why? Because when the dishes have been cleared away and the cigars passed, hell will no doubt break loose and the alibis will flow. These usually last until 3pm and send the mob home with prize headaches. To be invited to a luncheon is to be fattened for the slaughter.

There is the process.

Continued in "Walt's People: Volume 18"!

In a long interview, animator Ken O'Connor talks about his career with Disney, his forced retirement and triumphant return, and his opinions about a few of his fellow Disney animators and artists.

RON MERK: Tell us a little about working with Ken Anderson.

KEN O'CONNOR: I thought he was a very brilliant guy. When he first came in, I thought he was old-fashioned and out of date [from a] cartoon thinking [standpoint]. But he proved to be really good at developing sequences to Walt’s satisfaction, which wasn’t easy, and developing and designing new characters. He was very good at that. He had a checkered career, when he first came in, almost the time I did, in 1935. Something went wrong and they put him out in the Machine Shop. They thought he had TB or something, some ailment that he had to be outdoors, and he couldn’t…. That was a terrible blow to him, to be told he couldn’t work indoors, because that was his life, in the studio, drawing and so on. Then he recovered from that, and he seemed to appear to come healthy.

RM: What was the project that you remember most closely working on with Ken?

KO: Well, actually, I was friends with him, but in the studio I had hardly any direct contact. The one time I seem to remember most was when he was a layout man, how he was for a while, and he was clever enough to get out of that. And he did a good pan of a stork flying away and back, in a picture I did, called Clock Cleaners. However, I just observed his work from afar, and he was a very good renderer.

RM: What was it like working with Art Babbitt?

KO: You’re touching on tender spots. Art Babbitt and I fell out at the time of the strike. I knew why they were striking, over the yellow-dog contracts, as they called them, that the studio was giving them. But my opinion was they should have talked first, and struck afterwards. They were a bunch of hotheads, and people of other inclinations, like [David] Hilberman, who decided to take the boys out. In those days, there was talk of a labor relations election to see if the Screen Cartoonists [Guild] would be our bargaining agent or not, and I have a feeling the boys felt that if we had an election they might lose it. So it was better to go out on strike and force the issue, rather than just go down quietly as a result of voting. I was completely against striking at that time. I understood what unions do: a thing that Walt never did. He was mystified by unions. He felt they were just against him, and that was it. So I had decided to become a strikebreaker, and I rode to work every day with a pipe wrench under the front seat of the car, thinking I might have to use it in self-defense because my dear friends were all climbing up telephone poles, and taking pictures of me to use at the union hall, and offering to turn my car over, and getting pretty offensive.

RM: Did you ever fall back in with Babbitt, and have to work with him?

KO: I was going to say I admired him. He did early, very good work in animation. And, of course, he was on the striker side. He and I had an argument. He met me on Dopey Drive, asking me why in the world I was a strikebreaker. I told him, and he hated me ever since, as far as I know. I didn’t think much of him because his thoughts were in the opposite direction.

RM: Were you ever in a situation where you were forced to work closely together, or were you always apart?

KO: I never worked closely in the studio with him. The only contact I had was this [strike] ruckus. I felt he was a very conceited man, and a man who held extreme positions. I’m not, so we didn’t get along.

RM: Tell us about working with Les Clark.

KO: I didn’t have much to do with him until Walt put in an educational unit. I worked for ten years with the layouts and doing these educationals. He was a very good-living chap. Generally, he was very nice to work with. He rushed in to bore me out one day, about something, and he got tired of punching me like a pillow, and after that he never bore me out again.

RM: How about Claude Coats?

KO: Claude was a marvelous background painter. In fact, he was called the paint machine. He had his mind so geared onto how to paint so that Technicolor would make it come out beautifully. Which meant you painted in the middle ranges, see. Technicolor tended to drop off darks into black, if they were below a certain value, and wash out lights, if they were above a level. He knew just where to work, and make it go in. Maybe the original didn’t look too strong, but once Technicolor hit it, and stepped up the contrast, it came out beautifully. He could paint regular decorative paintings, too, for his own amazement, which he did. I remember stuff I liked that he did, atmospheric stuff in Pinocchio, where Geppetto was looking for the puppet out in the street, and it was misty, and rainy, and foggy, and that’s pretty hard to do with this transparent sort of oil they used to post the colors, and he handled it just magnificently.

RM: Did you ever have to fight the Technicolor people to get them to do something the way you wanted it?

KO: No, I didn’t. See, I went in on the dailies, every day, and I had the capacity of a layout person, and I was very responsible because they wouldn’t shoot anything without it being painted and backgrounded and didn’t have my signature on it. I’d pull it through in the sweatboxes, and I had to look at them. I only had to say, “The yellow looks two points too strong,” and they’d take a note, and they’d change it. They didn’t question what I said at all, thank God. I had the authority of Walt behind me, you see. I was never excessively critical, but I could be quite picky, because I felt I had to be, in my own defense, because I was responsible, not only for staging the picture, but also to see that everything looked good, looked right. I got very expert there. They would flick scenes through the sweatbox, and I could pick out a flyspeck on one frame, and it’d hit me. I was geared to this nervous condition. So I’d say there was a mark on that frame, and they’d back up and play it slowly. Ham Luske, and some of these others, developed abilities to [spot] the most minute differences in sound and color and everything else, at just a frame or two, which was part of the reason Disney got credit for quality. We got fussy, and then they’d change it, and Walt got the credit. [Laughs]

RM: You said you were thrown out of the studio.

KO: That’s right. I think it goes back to J. F. Kennedy. He had a bunch of guys, they were called young Turks, and they apparently instituted this idea that people should retire when they’re 65, period. It became quite general in business. And I was called in one day, and they asked if I was 65. They knew damn well I was 65. The man said, “We’d like you to take retirement.” I said, “Okay, all right, I’ll see you later.” And that was it. At that time, they were throwing the gold out of Fort Knox as fast as they could pick it up. A number of people, anyone who got near that age, was pushed out, and that’s all there was to it. I know that guys like Jack Cummings…. It was unceremonious.

RM: You went back to Disney a few times to consult on some things, and for them to re-mine the gold that they—

KO: After a while, there was no gold. Their credit wasn’t too good. I wasn’t the only one who had to retire. I was at the top of my artistic form, I would say, and getting better, if anything. Because I’ve always studied and practiced, and creative people are like that, some of them.

I got other work from guys like Ben Sharpsteen, for instance, who was putting Calistoga, up north of San Francisco, on the map. He gave them a museum. He needed a muralist and they called me up. So I did a 46-foot mural for him, and damn near froze to death. There was no heat in the place. Anyway, I seemed to get a continuity of work. After a short while, Disney asked me, for the second time, if I’d teach at CalArts. I had refused to before because I didn’t think they were doing it the way Walt wanted it, or would have even put up with. So I said yes, and I went and I taught for three years there, and then I pulled out because I wanted to be more creative than repetitive.

Then they started Tokyo Disneyland, and they called me back for that. So I worked with Imagineering, and then I made a film called Meet the World, that I made entirely out of Japanese prints, which I thought looked pretty good. That was satisfactory. Then they had a thing called Epcot.

Walt had taken me and others in the plane back [in the days] to look at the site, and it was just a black lake. They had to drain the whole damn lake there. These cypress, all these trees blackened the stuff with their juice, and had to be completely taken out, and new water put in. That’s what we saw there that time. It wasn’t any Disney then. I was a barman on the plane, which was a terrible thing because I didn’t know how to be a barman. Here I was a barman with Roy Disney and Walt, but thank God they just drank whiskey, steadily.

When they did the World Showcase and those things, for General Motors, I made a film with Collin Campbell on the history of transportation. Then I did stuff on the history of energy, for Exxon. Since then, they subbed the job out to a guy up here who made another film for Disney-MGM Studios, called Return to Neverland, and I set the color on that, and it runs 300 times a day, I guess, back there.

RM: You’ve also done some work on their recent features.

KO: Yes, I’m told, now, that I’m consultant to the Animation Department, although in the last year or so they haven’t remembered I’m alive, I guess. I worked on The Little Mermaid. I did what they call “visual development”. I did inspirational paintings of what Ariel’s room of treasures under the sea might look like, what she had up there. They changed it completely before it got on the screen. And I designed some characters and some systems that they could use, of layout. When you’re flying like a merman or a mergirl, you’re not limited by gravity, and so you come along, and there’s a big cliff, and they just go right down the cliff on the bottom. Things that—when you’re young, you dream you can fly, and you can do things that you can’t. This is like the relaxation of your imagination. And I also designed a wonderful sea witch, which they didn’t use. They used an old whore, I mean madam, who had been cut off at the waist and jammed into a decapitated octopus.

RM: What did your Ursula look like?

KO: I thought what they got didn’t look as if she came from the sea. There’s a real woman’s torso, you know, and this looks of the land, although I made mine out of the great manta ray, those huge great big things that fly through the sea, and they have a black, built-in cape, see. They go like this, with those wings. The manta rays don’t do it, but she could. And I was gonna have a head, and a body, underneath, and a stingray if necessary. At the point of black hat, and the point of the black manta rays, I thought they’re beautiful to see, and they look as if they’re out of the sea, you know, that shape, like a fishy shape, and I thought it would be great when she swept her cape around because she can have this kind of a wand, if you want, and her black cape can be her own wings. But they didn’t use it in the picture, and I thought mine was much more appropriate.

Continued in "Walt's People: Volume 18"!

About Theme Park Press

Theme Park Press is the world's leading independent publisher of books about the Disney company, its history, its films and animation, and its theme parks. We make the happiest books on earth!

Our catalog includes guidebooks, memoirs, fiction, popular history, scholarly works, family favorites, and many other titles written by Disney Legends, Disney animators and artists, Mouseketeers, Cast Members, historians, academics, executives, prominent bloggers, and talented first-time authors.

We love chatting about what we do: drop us a line, any time.

Theme Park Press Books

The Unauthorized Story of Walt Disney's Haunted Mansion The Ride Delegate 501 Ways to Make the Most of Your Walt Disney World Vacation The Cotton Candy Road Trip The Wonderful World of Customer Service at Disney Disney Destinies Disney Melodies The Happiest Workplace on Earth Storm over the Bay A Historical Tour of Walt Disney World: Volume 1 Mouse in Transition Mouseketeers Down Under Murder in the Magic Kingdom Walt Disney and the Promise of Progress City Service with Character Son of Faster Cheaper A Tale of Two Resorts I Saw Ariel Do a Keg Stand The Adventures of Young Walt Disney Death in the Tragic Kingdom Two Girls and a Mouse Tale Ears & Bubbles The Easy Guide 2015 Who's the Leader of the Club? Disney's Hollywood Studios Funny Animals Life in the Mouse House The Book of Mouse Disney's Grand Tour The Accidental Mouseketeer The Vault of Walt: Volume 1 The Vault of Walt: Volume 2 The Vault of Walt: Volume 3 Who's Afraid of the Song of the South? Amber Earns Her Ears Ema Earns Her Ears Sara Earns Her Ears Katie Earns Her Ears Brittany Earns Her Ears Walt's People: Volume 1 Walt's People: Volume 2 Walt's People: Volume 13 Walt's People: Volume 14 Walt's People: Volume 15

Write for Theme Park Press

We're always in the market for new authors with great ideas. Or great authors with new ideas. Whichever type of author you are, we'd be happy to discuss your book. Before you contact us, however, please make sure you can answer "yes" to these threshold questions:

Is It Right for Us?

We specialize in books that have some connection to Disney or theme parks. Disney, of course, has become a broad topic, and encompasses not just theme parks and films but comic books, animation, and a big chunk of pop culture. Your book should fit into one (or more) of those broad categories.

Is It Going to Make Money?

There's never a guarantee that any book will make money, but certain types of books are less likely to do so than others. They include: hardcovers, books with color photos, and books that go on forever ("forever" as in 400+ pages). We won't automatically turn down these types of books, but you'll have to be a really good salesman to convince us.

Are You Great to Work With?

Writing books and publishing books should be fun. The last thing you want, and the last thing we want, is a contentious relationship. We work with authors who share our philosophy of no drama and zero attitude, and the desire for a respectful, realistic, mutually beneficial partnership.

If you said "yes" three times, please step inside.