- Visit the Imagineering Graveyard

- Now Sailing: "Skipper Stories" - Tales from the Jungle Cruise

- Coming Soon: The biography of Disney animator Jack Hannah

- Coming Soon: A Haunted Mansion anthology

Walt's People: Volume 16

Talking Disney with the Artists Who Knew Him

by Didier Ghez | Release Date: December 23, 2015 | Availability: Print, Kindle

Disney History from the Source

The Walt's People series is an oral history of all things Disney, as told by the artists, animators, designers, engineers, and executives who made it happen, from the 1920s through the present.

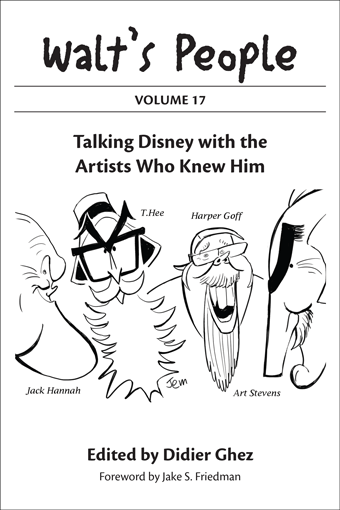

Walt’s People: Volume 16 features appearances by Lorina Coomber Butler, Leigh Harline, Jim MacDonald, Woolie Reitherman, T. Hee, Jack Hannah, Frank Thomas and Ollie Johnston, Ken Anderson, Dan Doonan, Jack Bruner, Art Stevens, Bill Anderson, Bob McCrea, General Joe Potter, Harper Goff, and Phil Mendez, plus a short autobiography by Bill Wright and an article by Mary Lou Whitman about her job as a color supervisor at the Disney Studio in the late 1930s.

Among the hundreds of stories in this volume:

- FRANK THOMAS AND OLLIE JOHNSTON chat about their long careers at the Disney Studio as two of Walt Disney’s “Nine Old Men”, their lifelong friendship, and the politics and philosophies of animation.

- BILL ANDERSON shoots from the hip with his candid comments about Walt and Roy Disney, Disney artists and animators, and how close the studio came to disbanding Feature Animation after Walt's death.

- GENERAL JOE POTTER shares war stories about the many challenges he overcame during the construction of Walt Disney World.

- HARPER GOFF reflects upon his relationship with Walt, his years as an Imagineer with WED, and his work on such films as 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea, in a unique book-length narrative.

The entertaining, informative stories in every volume of Walt's People will please both Disney scholars and eager fans alike.

Table of Contents

Welcome to Walt's People!

Foreword

Introduction

Lorina Coomber Butler by Dave Smith

Leigh Harline by R. Vernon Steele

Jim MacDonald by John Culhane

Woolie Reitherman

T. Hee by John Culhane

My Job at Walt Disney’s

Jack Hannah

Frank Thomas and Ollie Johnston by Michael Barrier

Frank Thomas and Ollie Johnston by Michael Barrier

Ken Anderson by John Culhane

Ken Anderson by John Culhane

Dan Noonan by Bill Spicer and Vince Davis

The Autobiography of Bill Wright

Jack Bruner by Dave Smith

Art Stevens

Bill Anderson by Bob Thomas

Bill Anderson by Michael Broggie

Bob McCrea by Dave Smith

Bob McCrea by Bob Thomas

The “Lost” Joe Potter Interview by Sam Rosen

Harper Goff by Jay Horan

Phil Mendez by Didier Ghez

Further Reading

About the Authors

Foreword

Walt Disney: He smoked regularly, drank socially, loved chili, and created a baby the old-fashioned way.

Some fifty years after his death, he has been exalted as a dreamer who made it. He muscled his way through a world of hardship to make room for whimsy and fantasy. For that, he will forever be an individual folk hero.

But Walt lived. In his lifetime, he ran a groundbreaking studio with hundreds of artists—an exceptional feat. And the clearest window into that living man is not through shining the spotlight on him alone, but by illuminating those around him. These people were part of the process that made Walt into the stuff of legend.

My meeting with Walt Disney came in 1983. I was the target age for the newly launched Disney Channel. My parents had a hand-operated, wood-paneled VCR. Tapes and tapes of Disney Channel cartoons filled our shelves (back then you could watch blocks of classic cartoons during Good Morning Mickey, Donald Duck Presents, and Mouseterpiece Theater—hosted by George Plimpton). The network also aired the “lesser” Disney features, like Dumbo, Robin Hood, and Alice in Wonderland, and those, too, became my childhood.

We watched reruns of classic Disney shows like Zorro and The Mickey Mouse Club, but my favorite was anything hosted by Walt himself. For me, Uncle Walt was very much alive. His suit, his mustache, and his smile were as real as anything else in my world. I’m not sure when I learned that he had died, but it didn’t change his status in my mind. Contrariwise, it only added to his mystique and sainthood.

Growing up is a funny thing. The simplicities we’re taught at one age make way for the complexities we discover later. No one gives us a textbook of what really happened, we’re just entrusted to figure it out ourselves. I asked Mrs. Brown in 3rd grade why we only tell the story of the first Thanksgiving from the Pilgrims’ point of view. She naturally pointed out that the natives’ perspective would be a very different story.

We grow, we read, we discover. Just take a look. The deeper we go, the more human elements rise to the surface. People behaving like people. They’re not always squeaky clean, and their stories are never simple.

When I was eleven, I presented a book report on storyman Bill Peet’s autobiography. Peet’s depiction of Walt was of a no-nonsense boss with a short fuse. It was a surreal contrast to his television persona. Later, as a teen, I read animator Shamus Culhane’s memoir, and his account of the Disney Studio opened my mind even wider.

These were the days when the independent books about the Disney Studio were few and far between. It was also a time when animation meant pencils and graphite. Hell, I watched The Disney Afternoon, whose intro had Mickey placing paper over a pegboard. Talk about the old days. If it were remade now, the Mouse might be clicking a mouse.

It seems that, as the animation medium turns increasingly digital, we grow more nostalgic for the old days. People don’t use pegboards very much anymore, but we want to know what it was like when they did. And it seems that as a culture, we’re ready to hear those stories, to go beyond the TV persona. We appreciate Walt for more than just his suit and his smile—neither of which he wore as much as we thought. We have matured, as has our view of Walt as a fascinatingly complex figure.

Walt Disney: he couldn’t draw that well, he loved his family, and he could inspire the largest team of artistic talent outside the European Renaissance. Those voices testify here in these pages.

Introduction

As I write these lines, Theme Park Press is about to release the 1940s autobiography of story artist and Goofy’s voice, Pinto Colvig, It’s a Crazy Business. This would not have happened without the persistence of my good friend and fellow Disney historian, Todd James Pierce, who spent years lobbying the Oregon Historical Society, who own the book’s copyright.

“Be very persistent” is key to the success of any Disney historian.

A year ago, while conducting research on the second volume of They Drew as They Pleased, I contacted the son of animator and story artist Retta Scott. I wanted to know if he had preserved any documents related to his mother’s Disney career. He mentioned that he only had a few autobiographical notes written by Retta. That was excellent news, but I wondered if that was really all he had. I kept insisting and he kept mentioning that he had nothing else.

While reading the notes, I noticed that Retta, after 30 years out of the business, had come back to animation in the ’80s, at the end of her career and right before her death. I decided to track down artists who had worked with her at the time. While interviewing one of them, I learned that Retta had once shown that artist the mock-up of a book called B-1st that she had designed with fellow Disney artist Woolie Reitherman in 1941. I emailed Retta’s son right away to find out if he knew anything about that book, and he emailed back letting me know that he actually had the book! If he had that book and had not mentioned it, what else did he have?

I spent the next few weeks insisting politely, and after a while, he realized that he had a few documents that might be of interest to me—as in over a hundred pieces of never-seen-before Disney concept art by his mother. In other words: be polite, but be persistent!

Being persistent is not enough, however. You also have to have a good sense of timing. A few days ago, I sent an email to a fellow animation enthusiast. For close to ten years I had been trying to locate the memoir of a Disney story artist from the 1950s and I thought that this animation enthusiast might be able to help. I asked him if he knew how I could contact the granddaughter of the artist (since both the artist and his daughter were long gone). He told me to re-contact him in three months since he was too busy to help at the moment. That was a Thursday morning. On the Friday morning he emailed me again, this time to ask me to call him right away, which I did in a heartbeat. He had stunning news for me: a few hours after he had first emailed me back, he had heard from the granddaughter of the Disney artist, who called to have breakfast with him on Sunday morning in Los Angeles. He had not heard from her in three years and she lived in Rome, Italy. If I had emailed him just a few days later…

This is the story of how, day in, day out, we stumble upon the treasures that are released in Walt’s People and other Disney history books.

This specific volume features quite a few treasures. My favorites: the rare essay by Disney’s publicist Janet Martin about her trip to Latin America in 1941, written for her sorority magazine; the lecture about Man in Space by Art Stevens at CalArts; and the in-depth interview of Imagineer Harper Goff by Jay Horan. I am certain that you will find many others that you will love in this very eclectic volume.

Didier Ghez

Didier Ghez has conducted Disney research since he was a teenager in the mid-1980s. His articles about the Disney parks, Disney animation, and vintage international Disneyana, as well as his many interviews with Disney artists, have appeared in Animation Journal, Animation Magazine, Disney Twenty-Three, Persistence of Vision, StoryboarD, and Tomart’s Disneyana Update. He is the co-author of Disneyland Paris: From Sketch to Reality, runs the Disney History blog, the Disney Books Network, and serves as managing editor of the Walt’s People book series.

A Chat with Didier Ghez

If you have a question for Didier that you would like to see answered here, please get in touch and let us know what's on your mind.

About The Walt's People Series

How did you get the idea for the Walt's People series?

GHEZ: The Walt’s People project was born out of an email conversation I conducted with Disney historian Jim Korkis in 2004. The Disney history magazine Persistence of Vision had not been published for years, The “E” Ticket magazine’s future was uncertain, and, of course, the grandfather of them all, Funnyworld, had passed away 20 years ago. As a result, access to serious Disney history was becoming harder that it had ever been.

The most frustrating part of this situation was that both Jim and I knew huge amounts of amazing material was sleeping in the cabinets of serious Disney historians, unavailable to others because no one would publish it. Some would surface from time to time in a book released by Disney Editions, some in a fanzine or on a website, but this seemed to happen less and less often. And what did surface was only the tip of the iceberg: Paul F. Anderson alone conducted more than 250 interviews over the years with Disney artists, most of whom are no longer with us today.

Jim had conceived the idea of a book originally called Talking Disney that would collect his best interviews with Disney artists. He suggested this to several publishers, but they all turned him down. They thought the potential market too small.

Jim’s idea, however, awakened long forgotten dreams, dreams that I had of becoming a publisher of Disney history books. By doing some research on the web I realized that new "print-on-demand" technology now allowed these dreams to become reality. This is how the project started.

Twelve volumes of Walt's People later, I decided to switch from print-on-demand to an established publisher, Theme Park Press, and am happy to say that Theme Park Press will soon re-release the earlier volumes, removing the few typos that they contain and improving the overall layout of the series.

How do you locate and acquire the interviews and articles?

To locate them, I usually check carefully the footnotes as well as the acknowledgments in other Disney history books, then get in touch with their authors. Also, I stay in touch with a network of Disney historians and researchers, and so I become aware of newly found documents, such as lost autobiographies, correspondence with Disney artists, and so forth, as soon as they've been discovered.

Were any of them difficult to obtain? Anecdotes about the process?

Yes, some interviews and autobiographical documents are extremely difficult to obtain. Many are only available on tapes and have to be transcribed (thanks to a network of volunteers without whom Walt’s People would not exist), which is a long and painstaking process. Some, like the seminal interview with Disney comic artist Paul Murry, took me years to obtain because even person who had originally conducted the interview could not find the tapes. But I am patient and persistent, and if there is a way to get the interview, I will try to get it, even if it takes years to do so.

One funny anecdote involves the autobiography of the Head of Disney’s Character Merchandising from the '40s to the '70s, O.B. Johnston. Nobody knew that his autobiography existed until I found a reference to an article Johnston had written for a Japanese magazine. The article was in Japanese. I managed to get a copy (which I could not read, of course) but by following the thread, I realized that it was an extract from Johnston’s autobiography, which had been written in English and was preserved by UCLA as part of the Walter Lantz Collection. (Later in his career Johnston had worked with Woody Woodpecker’s creator.) Unfortunately, UCLA did not allow anyone to make copies of the manuscript. By posting a note on the Disney History blog a few weeks later, I was lucky enough to be contacted by a friend of Johnston's family, who lives in England and who had a copy of the manuscript. This document will be included in a book, Roy's People, that will focus on the people who worked for Walt's brother Roy.

How many more volumes do you foresee?

That is a tough question. The more volumes I release, the more I find outstanding interviews that should be made public, not to mention the interviews that I and a few others continue to conduct on an ongoing basis. I will need at least another 15 to 17 volumes to get most of the interviews in print.

About Disney's Grand Tour

You say that you've worked on this book for 25 years. Why so long?

DIDIER: The research took me close to 25 years. The actual writing took two-and-a-half years.

The official history of Disney in Europe seemed to start after World War II. We all knew about the various Disney magazines which existed in the Old World in the '30s, and we knew about the highly-prized, pre-World War II collectibles. That was about it. The rest of the story was not even sketchy: it remained a complete mystery. For a Disney historian born and raised in Paris this was highly unsatisfactory. I wanted to understand much more: How did it all start? Who were the men and women who helped establish and grow Disney's presence in Europe? How many were they? Were there any talented artists among them? And so forth.

I managed to chip away at the brick wall, by learning about the existence of Disney's first representative in Europe, William Banks Levy; by learning the name George Kamen; and by piecing together the story of some of the early Disney licensees. This was still highly unsatisfactory. We had never seen a photo of Bill Levy, there was little that we knew about George Kamen's career, and the overall picture simply was not there.

Then, in July 2011, Diane Disney Miller, Walt Disney's daughter, asked me a seemingly simple question: "Do you know if any photos were taken during the 'League of Nations' event that my father attended during his trip to Paris in 1935?" And the solution to the great Disney European mystery started to unravel. This "simple" question from Diane proved to be anything but. It also allowed me to focus on an event, Walt's visit to Europe in 1935, which gave me the key to the mysteries I had been investigating for twenty-three years. Remarkably, in just two years most of the answers were found.

Will Disney's Grand Tour interest casual Disney fans?

DIDIER: Yes, I believe that casual readers, not just Disney historians, will find it a fun read. The book is heavily illustrated. We travel with Walt and his family. We see what they see and enjoy what they enjoy. And the book is full of quotes from the people who were there: Roy and Edna Disney, of course, but also many of the celebrities and interesting individuals that the Disneys met during the trip. And on top of all of this, there is the historical detective work, that I believe is quite fun: the mysteries explored in the book unravel step by step, and it is often like reading a historical novel mixed with a detective story, although the book is strict non-fiction.

Walt bought hundreds of books in Europe and had them shipped back to the studio library. Were they of any practical use?

DIDIER: Those books provided massive new sources of inspiration to the Story Department. "Some of those little books which I brought back with me from Europe," Walt remarked in a memo dated December 23, 1935, "have very fascinating illustrations of little peoples, bees, and small insects who live in mushrooms, pumpkins, etc. This quaint atmosphere fascinates me."

What other little-known events in Walt's life are ripe for analysis?

DIDIER: There are still a million events in Walt's life and career which need to be explored in detail. To name a few:

- Disney during WWII (Disney historian Paul F. Anderson is working on this)

- Disney and Space (I am hoping to tackle that project very soon)

- The 1941 Disney studio strike

- Walt's later trips to Europe

The list goes on almost forever.

Other Books by Didier Ghez:

- They Drew as They Pleased: The Hidden Art of Disney's Golden Age (2015)

- Disney's Grand Tour: Walt and Roy's European Vacation, Summer 1935 (2013)

- Disneyland Paris: From Sketch to Reality (2002)

Didier Ghez has edited:

- Walt's People: Volume 15 (2014)

- Walt's People: Volume 14 (2014)

- Walt's People: Volume 13 (2013)

- Walt's People: Volume 12 (20xx)

- Walt's People: Volume 11 (20xx)

- Walt's People: Volume 10 (20xx)

- Walt's People: Volume 9 (20xx)

- Walt's People: Volume 8 (20xx)

- Walt's People: Volume 7 (20xx)

- Walt's People: Volume 6 (20xx)

- Walt's People: Volume 5 (20xx)

- Walt's People: Volume 4 (20xx)

- Walt's People: Volume 3 (2015)

- Walt's People: Volume 2 (2015)

- Walt's People: Volume 1 (2014)

- Life in the Mouse House: Memoir of a Disney Story Artist (2014)

- Inside the Whimsy Works: My Life with Walt Disney Productions (2014)

Frank Thomas and Ollie Johnston talk to animation historian Michael Barrier about the politics of animation at the Disney Studio.

MICHAEL BARRIER: Was Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs the real turning point, as far as the animators taking on more responsibility for the staging?

FRANK THOMAS: I think that was a very gradual thing, depending upon which animator was working with which director, which layout man, and how Walt felt about what he was getting. We were in a very frustrating spot because, say you were working under Geronimi, and Geronimi was working under Ben Sharpsteen, and Ben was getting the word from Walt. You’re way down at the end of the line, and you’re not sure that even if Geronimi heard the correct comments from Walt, he would pass it on to you correctly. The same applied to Ben, and they felt the same way about us. And you couldn’t get to Walt to find out what he had said. It might have been a casual little statement like, “Oh, I think we ought to wait and see what he’s going to do here.” But by the time you got it, it might be interpreted as, “ I don’t think Frank can handle this stuff very well.” Walt maybe hadn’t said that at all, and yet there were two different interpretations by the time it got to you.

OLLIE JOHNSTON: That was an attitude Geronimi would then take.

FT: Because he thought that was what Walt had said. And until you got in a sweatbox, and showed your stuff to Walt, and he would tell you what he thought—he would jolly well tell you what he thought—and he’d tell Geronimi what he thought. So that everybody then knew. But as long as you were passing the word from Walt on down…

OJ: That was a difficult period.

FT: And occasionally Walt would say to Ben, or Gerry, or whoever it happened to be, “Just let Ollie go for a few scenes, see what he comes up with, he might surprise us all.” So then, hands off, let the animator lead on it. Other times, he’d say, “They don’t seem to be getting hold of it, let’s get in there and make sure what we’re doing.” There was no set procedure.

OJ: I remember a specific case, on Sleeping Beauty, we had just done a few scenes, and we were going to start on another section. I remember Walt saying, “Why don’t we let Frank get in there and work this out the way he does?” In other words, he was putting his confidence in him to work out the business, the cutting and everything, and develop it. We had a storyboard, and we had a running reel on it, but I remember specifically him saying that. So it worked both ways. If he felt he was going to get the best results that way, he’d do it. If he felt he was going to get the best results by having Geronimi badger us, he’d do it that way.

FT: And he was quick to change his mind, depending on what he saw. He might have put someone in charge; he hated titles, and he hated—

OJ: —setting anybody up with authority.

FT: One of the funniest incidents, from our standpoint, was when someone thought they had been set up with authority—and maybe they actually had, in words, they’d been told, “You’re in charge here, you see that this gets done”—and then Walt would go out and undercut them, in the next half hour, tell everybody else, “Watch out for that guy, he thinks he’s the boss, he’s trying to tell you what to do, don’t you pay any attention to him.”

OJ: He always set somebody up to counter somebody else. I remember on Bambi, Harry Tytle sent around that memo, about footage, and the same day, [Walt] told Dave Hand that what he really wanted on here was quality, and not to worry about the footage. He had one guy worrying about the footage, and sending memos to us, and Dave working from the other side.

FT: But you see, Walt’s feeling on that—and there’s a validity to it—was that if you called everyone together and said, “Look, fellows, we can’t spend too much money here, we have to be careful,” then everyone’s going to be wishy-washy. He wanted positive, he wanted aggressive, he wanted fighters. And so he would put one guy against another, and that way, one guy’s going to be working all the time to hold expenses down, the other guy’s going to be working for quality, and they’re going to get mad at each other, and they’re both going to work harder than they would otherwise, and Walt’s going to back them each up, and every day tell them, “Now watch that guy, you’re not going to let him put anything over on you.” So they each worked harder, and as a result, you got the best quality you could for the best price you could.

OJ: The animators really had enough pride, and of course, you didn’t want Walt jumping all over you, so you were going to see that your stuff was good, one way or another, no matter how hard you had to work at it to turn out the footage.

MB: Did he in effect pit animators and directors against one another as well? Ward Kimball tells stories about his conflicts with directors. Was this part of the same pattern?

OJ: He liked to stir things up. He didn’t like things to get too peaceful.

FT: If he felt three guys were working together, hand in glove, he was quick to break it up.

MB: He thought friction was creative?

OJ: He didn’t want them fighting with each other.

FT: Stimulation would be a better word than friction. Occasionally, of course, it would work the other way, it would kill your creative drive [because there was] too much opposition. That was the chance he was taking. But I think he recognized that.

OJ: I don’t ever remember a place where he was setting up animators who had a conflict, though. We usually worked quite well together. It was more between the story and direction, or between the direction and animation.

FT: I think the thing that Walt realized was that the drawings on the screen were where it’s at; and only the animator could put those there. Walt knew how to direct, he knew how to do story, he knew how to do everything else except animation. If he didn’t agree, or he questioned what somebody might do, he was more apt to turn an animator loose than he was a director.

OJ: He could give you a rough time, too; still, we always felt we were, in a way, a chosen few.

Continued in "Walt's People: Volume 17"!

Bill Anderson's recounts some of his many unique encounters with Walt Disney.

BOB THOMAS: Did Roy ever try to discourage Walt from building the thing [Disneyland]?

BILL ANDERSON: He tried to get him to commit and then stick with that commitment. It was like when Walt’s building a picture, Walt had a better idea than anybody did about what a picture could do. He was very shrewd. He knew when he had made a clunker. I’ve worked with a lot of people in this business and he always knew how to improve the product. That’s one of the greatest abilities he had was to see that something that he was setting up to do, how he could improve it. So he just kept doing it. That’s why his cartoons took so long and cost so much money. It wasn’t that we didn’t know how to do it, it was just that he wouldn’t let loose of it until it was as near right as he could get it. He was a master at going in and seeing that something wasn’t really working. So Roy, on the last meeting, Roy would say, “OK, Walt said this is the way we’re going to go.” And he meant it, but he didn’t mean it tomorrow if he saw a way to do it better. He was fabulous. I never saw him ever ruin anything, except one or two he got caught up in.

BT: Pictures?

BA: Yeah. But, anyway, that was a great problem for Roy. Roy would come to me and say, “Can’t you handle your budget? Can’t you do it ?” And you just couldn’t. He didn’t have anyone else to blame, so he blamed me. But he was very, very good. I admired him very much.

BT: That was a big job, financing the place.

BA: Oh, it was! Terrible.

BT: The ABC deal helped, but he still had to get some backers.

BA: Oh, yeah, he had to get it from the publishing people [Western Publishing], the same amount. Walt called me one time, and he said, “Bill, are you free this morning at eleven o’clock?” I said, “Yeah, I’m just going down on the stage.” He said, “If you could be back here, I’d appreciate it.” So I came back and it was the day that Leonard Goldenson was there. The years had gone by and the Disneys wanted to pay off ABC. Leonard was there trying to talk Walt into not paying off that bill. The way it was set up, there’s no question Disney had the right, but Leonard was leaning. He had talked to Roy. Roy had told him he was going to pay it off and Leonard didn’t want it. I just thought, “How the worm turns,” because Leonard saw Disney as a great asset for ABC and he wanted to keep that in there so that if anything ever happened he might be able to move in for Disney.

BT: You think so?

BA: Sure. He couldn’t get anywhere and he couldn’t talk to Walt the way he wanted to with me there. Walt had told me, “Don’t you leave this room. I don’t care if they call you from the stage or anyplace. Don’t you leave this room until Leonard leaves!”

BT: What did they talk about?

BA: They talked all around. We had a lot of [garbled], but he never would get down to it because Walt wouldn’t bite. Walt wouldn’t bite. It was a delicious experience for me. I’ve seen Leonard several times since and all he does is kind of look at me like he’s going to kill me. It wouldn’t have done him any good. Walt just didn’t want to be in that position.

BT: He finally had to sue ABC.

BA: Yeah.

BT: Then they finally did settle.

BA: Sure.

BT: But it was a sweet deal for ABC.

BA: Oh, sure. But that’s not what Leonard wanted. Leonard knew the real cookie was right there if he could get his hands on it.

BT: Isn’t it ironic?

BA: Yes! That’s just what I’m saying, isn’t that ironic the way the whole thing has twisted?

BT: Of course, Goldenson is no longer in charge.

BA: He was a very interesting guy. Leonard was a shrewd guy. He could see that whole thing the way the park eventually went: he didn’t want to get his money out of there.

BT: Where he made a mistake was cancelling The Mickey Mouse Club and Zorro and not letting Disney sell it to another network. That was the opening I’m sure Roy wanted.

BA: Yeah, but those are the kind of deals that he wanted to negotiate with Walt. Walt didn’t want any negotiations. Walt knew the value of Disneyland and the whole park idea. He didn’t want anyone getting their fingers in it.

BT: Do you think Roy warned Walt what Goldenson was after?

BA: I’m sure, yes! That’s the only reason Walt knew there was no sense in having Roy there, because Roy and Leonard had already crossed swords. He just didn’t want Leonard to get him. He just wanted someone there. He just wanted somebody there. When Leonard brought up about mutual values and all that, Walt said, “Leonard, I’ve got something over here that I’m kind of working on.” He just kept it very fluid and he would never let Leonard get off his base at all.

BT: Smart.

BA: But Roy had that problem for so many years. Always the same problem, because of Walt going through the problems of the war and their markets being closed off and Walt trying to keep his organization together. He knew that the real value was in that organization. It wasn’t that Walt couldn’t work with any organization, but Walt always worked the best when he was working with people that he had confidence in and he knew that they were loyal. We had individuals there that didn’t work too well with Walt or thought they had a better way of doing something. He couldn’t work in that atmosphere. You didn’t have to be a yes man with Walt or with Roy. You could say what you believed, and if they believed that you were straight and honest about it, by god they’d accept you standing up to them. Some people say that I was a yes man for Walt. I wasn’t a yes man for Walt. I certainly “yessed” him plenty, but when I was put to the point, I could stand up and say to Walt… Like when we made the little dog picture, Old Yeller, I found the property. I immediately just read it in an old Collier’s magazine. It was in three issues. I read the first one. I read that and I realized immediately that this had potential for something, a different kind of picture for Walt to make. So I immediately got to find out who owned it. I finally called Collier’s in New York for the publisher. They told me who the agent was in New York for the publishing. I finally found out that it was—who’s the wonderful tall guy that always wore the flower in his pocket that was the agent? I can’t think of his name.

Anyway, I called him and he didn’t know anything about the property at all. I said, “Who is the writer?” and he said, “I know I have it, but I’ll have to get back to you with it.” So he got back to me and he said it was a writer down in Texas. I said, “I’m the first one to call you.” It was kind of a thing in Hollywood then: whoever called him first had the first right at least to give him an answer. So we had a grab on it. To make a long story short, I called back the publisher and got the advanced issues, had them send them right out to me, and I read it all and I took it to Walt. I said, “It’s a little different for you to make, but I think it’s a picture we really need to make.” The minute Walt thought you were selling him something, that hide came up. Anyway, he wouldn’t give me an answer. I’m only telling you all this to show that you could stand up to him. Finally, he was going to leave to go someplace and he hadn’t given me an answer yet and the agent was calling me saying MGM had heard about this property. They were kind of interested in it. I said, “Look, I haven’t had a word out of Walt, but I’ll get it.” So I approached Walt and he put his jacket down and he said, “That property wouldn’t even make a good TV show.” I sat down and said, “Walt, you haven’t read all that material. If you’d read that, you couldn’t say it.” He just kept looking at me like you are and I looked at him and didn’t blink either and he finally said, “You’re through with your drink, aren’t ya?” I said, “Yes,” and he said, “I’m through with mine.” I went home, it was dark, and it was a Friday night or something. Sunday morning the phone rang.

[Audio cut out]

BA: I said, “We’re going to have to pay more for it,” because I had heard from Swanson. I had heard from him that MGM was ready to make an offer. I said, “We’re going to have to pay more money than we’ve ever paid for a property of this nature.” He said, “I didn’t ask you how much to pay for it. I just said buy it.” It shows you with Walt… I think if I had said that to him about some frivolous kind of thing, Walt would have probably said, “I don’t know that I need you,” or whatever. But if you really believed in what you wanted to do, now he may not agree with you, but by god he wouldn’t hold it against you as long as you didn’t nag him about it or try to make it an issue. Roy was quite similar.

BT: How much did you have to pay for that?

BA: It was only $50,000, but at that time we weren’t paying that kind of money.

Continued in "Walt's People: Volume 17"!

About Theme Park Press

Theme Park Press is the world's leading independent publisher of books about the Disney company, its history, its films and animation, and its theme parks. We make the happiest books on earth!

Our catalog includes guidebooks, memoirs, fiction, popular history, scholarly works, family favorites, and many other titles written by Disney Legends, Disney animators and artists, Mouseketeers, Cast Members, historians, academics, executives, prominent bloggers, and talented first-time authors.

We love chatting about what we do: drop us a line, any time.

Theme Park Press Books

The Unauthorized Story of Walt Disney's Haunted Mansion The Ride Delegate 501 Ways to Make the Most of Your Walt Disney World Vacation The Cotton Candy Road Trip The Wonderful World of Customer Service at Disney Disney Destinies Disney Melodies The Happiest Workplace on Earth Storm over the Bay A Historical Tour of Walt Disney World: Volume 1 Mouse in Transition Mouseketeers Down Under Murder in the Magic Kingdom Walt Disney and the Promise of Progress City Service with Character Son of Faster Cheaper A Tale of Two Resorts I Saw Ariel Do a Keg Stand The Adventures of Young Walt Disney Death in the Tragic Kingdom Two Girls and a Mouse Tale Ears & Bubbles The Easy Guide 2015 Who's the Leader of the Club? Disney's Hollywood Studios Funny Animals Life in the Mouse House The Book of Mouse Disney's Grand Tour The Accidental Mouseketeer The Vault of Walt: Volume 1 The Vault of Walt: Volume 2 The Vault of Walt: Volume 3 Who's Afraid of the Song of the South? Amber Earns Her Ears Ema Earns Her Ears Sara Earns Her Ears Katie Earns Her Ears Brittany Earns Her Ears Walt's People: Volume 1 Walt's People: Volume 2 Walt's People: Volume 13 Walt's People: Volume 14 Walt's People: Volume 15

Write for Theme Park Press

We're always in the market for new authors with great ideas. Or great authors with new ideas. Whichever type of author you are, we'd be happy to discuss your book. Before you contact us, however, please make sure you can answer "yes" to these threshold questions:

Is It Right for Us?

We specialize in books that have some connection to Disney or theme parks. Disney, of course, has become a broad topic, and encompasses not just theme parks and films but comic books, animation, and a big chunk of pop culture. Your book should fit into one (or more) of those broad categories.

Is It Going to Make Money?

There's never a guarantee that any book will make money, but certain types of books are less likely to do so than others. They include: hardcovers, books with color photos, and books that go on forever ("forever" as in 400+ pages). We won't automatically turn down these types of books, but you'll have to be a really good salesman to convince us.

Are You Great to Work With?

Writing books and publishing books should be fun. The last thing you want, and the last thing we want, is a contentious relationship. We work with authors who share our philosophy of no drama and zero attitude, and the desire for a respectful, realistic, mutually beneficial partnership.

If you said "yes" three times, please step inside.