- Visit the Imagineering Graveyard

- Now Sailing: "Skipper Stories" - Tales from the Jungle Cruise

- Coming Soon: The biography of Disney animator Jack Hannah

- Coming Soon: A Haunted Mansion anthology

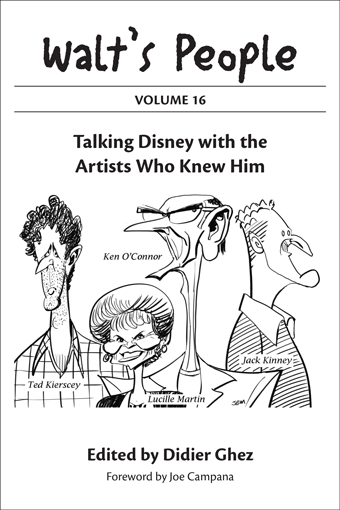

Walt's People: Volume 16

Talking Disney with the Artists Who Knew Him

by Didier Ghez | Release Date: July 6, 2015 | Availability: Print, Kindle

Disney History from the Source

The Walt's People series is an oral history of all things Disney, as told by the artists, animators, designers, engineers, and executives who made it happen, from the 1920s through the present.

Walt’s People: Volume 16 features appearances by Louis A. Pesmen, Grim Natwick, Gyo Fujikawa, Hicks Lokey, Jack Bradbury, Jack Kinney, Charles August "Nick" Nichols, Milt Kahl, Marc Davis, Bill Tytla, Ken Annakin, Irwin Kostal, Lucille Martin, Woolie Reitherman, Mel Shaw, Claude Coats, William "Sully" Sullivan, George McGinnis, Jack Buckley, and Ted Kierscey, plus an article by William M. Watkins about roller coaster design and excerpts from the November 1940 issue of The Bulletin (a weekly newsletter once published by the Disney studio) about the making of Fantasia.

Among the hundreds of stories in this volume:

- KEN ANNAKIN shares memories of his time spent with Walt Disney in England working on such films as Robin Hood and The Sword and the Rose.

- LUCILLE MARTIN provides unique insight about Walt Disney based on her many years of service as his personal secretary.

- WILLIAM "SULLY" SULLIVAN talks about his four decades with Disney, starting in 1955 on Walt's Jungle Cruise and ending with his retirement as vice-president of Magic Kingdom.

- GEORGE McGINNIS, an Imagineer and industrial designer, explains the nuts and bolts behind such attractions as Space Mountain, Horizons, and the Mark V monorail (which he designed).

The entertaining, informative stories in every volume of Walt's People will please both Disney scholars and eager fans alike.

Table of Contents

Foreword

Introduction

Louis A. Pesmen

Grim Natwick by Robin Allan

Articles from "The Bulletin"

Gyo Fujikawa

Gyo Fujikawa by John Canemaker

Hicks Lokey by Mark Langer

Excerpts from Jack Bradbury's Autobiography

Jack Kinney

Charles August "Nick" Nichols

Milt Kahl, Marc Davis, and Bill Tytla

Ken Annakin by EMC West

Irwin Kostal by Richard Holliss

Lucille Martin by Michael Broggie

Woolie Reitherman and Mel Shaw by Frank Thomas and Ollie Johnston

Claude Coats by Jay Horan

William "Sully" Sullivan by Jim Korkis

George McGinnis by Didier Ghez

Making Magic: How Computers Influenced Roller Coaster Design by William M. Watkins

Walt Disney World's Space Mountain by George McGinnis

Disneyland's Space Mountain by George McGinnis and William M. Watkins

Horizons by George McGinnis

On Track by George McGinnis

Jack Buckley by Bob Thomas

Ted Kierscey by Didier Ghez

Further Reading

About the Authors

Foreword

If you are interested in Walt Disney, it probably won’t be long before you become curious about the myriad of movies, television shows, theme parks, or even the company that bears his name.

Among the first questions that might come to mind are: How were all these things accomplished? How were the animated classic films created? What were the steps involved in designing and building the Disney theme parks? Of course, Walt Disney didn’t accomplish these things by himself. He might best be described as the conductor—leading an orchestra of talented artists, technicians, and managers.

Within the pages of this book, and to a far greater degree in the pages of the astounding fifteen volumes that precede it, you are able to read the first-hand accounts of the people in that “orchestra”, the people who worked with Walt Disney on the many projects that he set into motion during his active and varied career.

I wish to extend a heartfelt “Thank You” to Didier Ghez for undertaking the effort of getting these stories published. Who among us would have imagined the access we have been granted over the past decade to the hundreds of interviews and other stories contained in this series? To those of us who seek a clearer understanding of such matters, the books of the Walt’s People series stand among the best resources available.

In this book, you will find a wide range of interesting content extending beyond the realm of interviews: from the story of Walt’s first job in an art studio, as told by his employer, Louis Pesmen, to a multi-part examination of the projects of designer and Imagineer George McGinnis.

The interviews here include two with Gyo Fujikawa who was among the few early female artists at the studio outside of the Ink andPaint Department; Claude Coats, artist and Imagineer; animation directors “Nick” Nichols and Jack Kinney; live-action director Ken Annakin; music arranger and conductor Irwin Kostal; effects animators Jack Buckley and Ted Kierscey; character animators Grim Natwick and Hicks Lokey who each came to the Disney studio after having worked earlier for the Fleischer Studio in New York; and Lucille Martin, one-time secretary to Walt Disney who became the special assistant to the company’s board of directors.

Also here is an in-depth autobiography of animator Jack Bradbury; an informative panel discussion with character animators Milt Kahl, Marc Davis and Bill Tytla; a brief interview from the 1980s with Woolie Reitherman and Mel Shaw; an interview with “Sully” Sullivan who had an incredibly varied career at both Disneyland and Walt Disney World; and an article by William Watkins on the role of computers in roller coaster design.

Rounding out this collection are nine articles that originally appeared in a 1940 edition of the studio’s weekly newsletter, The Bulletin. Each was written by a different person and offers an interesting perspective on the production of Fantasia.

Most of the interviews in this series of books were conducted years (or decades) ago as research material for a book or magazine article and were never intended to be released in the nearly raw form presented here. Given that form, we are allowed insight into the organic nature of an interview—and how one’s memory can open doors to other recollections and a path to further questions.

I feel the need to make a point that can be easily overlooked. You, too, can sit down and conduct interviews! In fact, all the elements needed to accomplish this are remarkably easy to pull together. All you need is a subject to interview, a set of questions, and a device to record the session.

Not too many years ago, it took a fair amount of effort to record an interview. Not so in today’s world! Whether they know it or not, most everyone now carries a portable recorder with them. The smart phone in your pocket or purse is also a digital recorder. Learn to use it!

You will be surprised how enlightening it can be to conduct an interview—even with a member of your own family. You can start by asking questions of your parents, grandparents, or a favorite aunt or uncle. Ask them about the jobs they have had, the friends they knew, the cars they drove, what they did for fun, how they met their spouses.

Promise me that if, in the course of one of your interviews, you discover someone who happened to have worked with Walt Disney or for the Walt Disney Company, you will consider letting Didier know.

Introduction

When you conduct research, there is nothing more exhilarating than “the snowball effect”: a small discovery that leads to more and more discoveries.

A few weeks ago, I was reading a 1978 interview of Disney’s head of story research in the late ’30s, John Rose. The interview, conducted by Milt Gray for Michael Barrier, was fascinating in itself, but one short section, in which Rose mentioned an Ecuadorian artist called Eduardo Solá Franco, caught my attention. Rose was discussing Solá Franco’s work in 1939 and early 1940 on the abandoned Disney project Don Quixote. I had never heard of Eduardo Solá Franco and found myself googling him right away. And the discoveries started happening: Solá Franco had created, during his entire life, illustrated diaries of tremendous beauty. While studying those diaries, I realized that most of the paintings from Don Quixote reproduced in the book The Disney That Never Was and attributed to Bob Carr had in fact been painted by Solá Franco. This had the added benefit of solving an old mystery which had always puzzled me, since Bob Carr was a writer, not a visual artist (several of the paintings in The Disney That Never Was by an “unknown artist” and by Martin Provensen are also clearly the work of Solá Franco). But the discoveries did not stop there. I also located Solá Franco’s correspondence, which, if I manage to get access to it, might contain more revelations, historical treasures, and even leads to more discoveries.

Think this is a one-off? Think again. A few months ago, while working with historian Ross Care on the editing of his extensive correspondence with director Wilfred Jackson, I decided to try and locate the family of “Jaxon” with the help of my good friend Joe Campana. We managed to locate a granddaughter. A few years back, story artist Burny Mattinson had mentioned that Disney Legend Eric Larson had told him that, throughout his life, Wilfred Jackson had been writing a professional diary. When I spoke to Wilfred’s granddaughter, she told me that she was not aware of a diary, but she promised to look and tell me if she found something. A few weeks later she had found a lot of interesting material, but no diary. And then one day she called me with the news: the diary existed, and she had located it. The document will appear in the book that Ross and I are currently working on, but what ties it to the “snowball effect” story is that while reading it, I learned that one of the concept artists, whose life and career I am studying for my new book series (They Drew As They Pleased), Sylvia Holland, had worked on very early concepts for what would become Toot, Whistle, Plunk, and Boom. This led me to try and reconnect with Sylvia Holland’s family, which led to the discovery of one of the largest treasure troves ever uncovered by Disney historians. I have a feeling that its content will be mined for years to come and that it will lead to many more discoveries. You can start to recognize the pattern.

And so the principle which I keep expounding in those introductions remains truer than ever: the more you learn about Disney history, the likelier you are to make discoveries, which in turn will lead to more and more discoveries. Hence Walt’s People’s old battle cry: “Unlock the vaults!”

Two prominent historians, John Canemaker and Mark Langer, heard that cry loud and clear when they provided me with their fascinating interviews with Gyo Fujikawa and Hicks Lokey for this volume. And I thought that I could no longer be amazed!

But before you get to those gems and to the others that Walt’s People: Volume 16 has in store, let’s travel back to a time when the Disney studio did not even exist…

Didier Ghez

Didier Ghez has conducted Disney research since he was a teenager in the mid-1980s. His articles about the Disney parks, Disney animation, and vintage international Disneyana, as well as his many interviews with Disney artists, have appeared in Animation Journal, Animation Magazine, Disney Twenty-Three, Persistence of Vision, StoryboarD, and Tomart’s Disneyana Update. He is the co-author of Disneyland Paris: From Sketch to Reality, runs the Disney History blog, the Disney Books Network, and serves as managing editor of the Walt’s People book series.

A Chat with Didier Ghez

If you have a question for Didier that you would like to see answered here, please get in touch and let us know what's on your mind.

About The Walt's People Series

How did you get the idea for the Walt's People series?

GHEZ: The Walt’s People project was born out of an email conversation I conducted with Disney historian Jim Korkis in 2004. The Disney history magazine Persistence of Vision had not been published for years, The “E” Ticket magazine’s future was uncertain, and, of course, the grandfather of them all, Funnyworld, had passed away 20 years ago. As a result, access to serious Disney history was becoming harder that it had ever been.

The most frustrating part of this situation was that both Jim and I knew huge amounts of amazing material was sleeping in the cabinets of serious Disney historians, unavailable to others because no one would publish it. Some would surface from time to time in a book released by Disney Editions, some in a fanzine or on a website, but this seemed to happen less and less often. And what did surface was only the tip of the iceberg: Paul F. Anderson alone conducted more than 250 interviews over the years with Disney artists, most of whom are no longer with us today.

Jim had conceived the idea of a book originally called Talking Disney that would collect his best interviews with Disney artists. He suggested this to several publishers, but they all turned him down. They thought the potential market too small.

Jim’s idea, however, awakened long forgotten dreams, dreams that I had of becoming a publisher of Disney history books. By doing some research on the web I realized that new "print-on-demand" technology now allowed these dreams to become reality. This is how the project started.

Twelve volumes of Walt's People later, I decided to switch from print-on-demand to an established publisher, Theme Park Press, and am happy to say that Theme Park Press will soon re-release the earlier volumes, removing the few typos that they contain and improving the overall layout of the series.

How do you locate and acquire the interviews and articles?

To locate them, I usually check carefully the footnotes as well as the acknowledgments in other Disney history books, then get in touch with their authors. Also, I stay in touch with a network of Disney historians and researchers, and so I become aware of newly found documents, such as lost autobiographies, correspondence with Disney artists, and so forth, as soon as they've been discovered.

Were any of them difficult to obtain? Anecdotes about the process?

Yes, some interviews and autobiographical documents are extremely difficult to obtain. Many are only available on tapes and have to be transcribed (thanks to a network of volunteers without whom Walt’s People would not exist), which is a long and painstaking process. Some, like the seminal interview with Disney comic artist Paul Murry, took me years to obtain because even person who had originally conducted the interview could not find the tapes. But I am patient and persistent, and if there is a way to get the interview, I will try to get it, even if it takes years to do so.

One funny anecdote involves the autobiography of the Head of Disney’s Character Merchandising from the '40s to the '70s, O.B. Johnston. Nobody knew that his autobiography existed until I found a reference to an article Johnston had written for a Japanese magazine. The article was in Japanese. I managed to get a copy (which I could not read, of course) but by following the thread, I realized that it was an extract from Johnston’s autobiography, which had been written in English and was preserved by UCLA as part of the Walter Lantz Collection. (Later in his career Johnston had worked with Woody Woodpecker’s creator.) Unfortunately, UCLA did not allow anyone to make copies of the manuscript. By posting a note on the Disney History blog a few weeks later, I was lucky enough to be contacted by a friend of Johnston's family, who lives in England and who had a copy of the manuscript. This document will be included in a book, Roy's People, that will focus on the people who worked for Walt's brother Roy.

How many more volumes do you foresee?

That is a tough question. The more volumes I release, the more I find outstanding interviews that should be made public, not to mention the interviews that I and a few others continue to conduct on an ongoing basis. I will need at least another 15 to 17 volumes to get most of the interviews in print.

About Disney's Grand Tour

You say that you've worked on this book for 25 years. Why so long?

DIDIER: The research took me close to 25 years. The actual writing took two-and-a-half years.

The official history of Disney in Europe seemed to start after World War II. We all knew about the various Disney magazines which existed in the Old World in the '30s, and we knew about the highly-prized, pre-World War II collectibles. That was about it. The rest of the story was not even sketchy: it remained a complete mystery. For a Disney historian born and raised in Paris this was highly unsatisfactory. I wanted to understand much more: How did it all start? Who were the men and women who helped establish and grow Disney's presence in Europe? How many were they? Were there any talented artists among them? And so forth.

I managed to chip away at the brick wall, by learning about the existence of Disney's first representative in Europe, William Banks Levy; by learning the name George Kamen; and by piecing together the story of some of the early Disney licensees. This was still highly unsatisfactory. We had never seen a photo of Bill Levy, there was little that we knew about George Kamen's career, and the overall picture simply was not there.

Then, in July 2011, Diane Disney Miller, Walt Disney's daughter, asked me a seemingly simple question: "Do you know if any photos were taken during the 'League of Nations' event that my father attended during his trip to Paris in 1935?" And the solution to the great Disney European mystery started to unravel. This "simple" question from Diane proved to be anything but. It also allowed me to focus on an event, Walt's visit to Europe in 1935, which gave me the key to the mysteries I had been investigating for twenty-three years. Remarkably, in just two years most of the answers were found.

Will Disney's Grand Tour interest casual Disney fans?

DIDIER: Yes, I believe that casual readers, not just Disney historians, will find it a fun read. The book is heavily illustrated. We travel with Walt and his family. We see what they see and enjoy what they enjoy. And the book is full of quotes from the people who were there: Roy and Edna Disney, of course, but also many of the celebrities and interesting individuals that the Disneys met during the trip. And on top of all of this, there is the historical detective work, that I believe is quite fun: the mysteries explored in the book unravel step by step, and it is often like reading a historical novel mixed with a detective story, although the book is strict non-fiction.

Walt bought hundreds of books in Europe and had them shipped back to the studio library. Were they of any practical use?

DIDIER: Those books provided massive new sources of inspiration to the Story Department. "Some of those little books which I brought back with me from Europe," Walt remarked in a memo dated December 23, 1935, "have very fascinating illustrations of little peoples, bees, and small insects who live in mushrooms, pumpkins, etc. This quaint atmosphere fascinates me."

What other little-known events in Walt's life are ripe for analysis?

DIDIER: There are still a million events in Walt's life and career which need to be explored in detail. To name a few:

- Disney during WWII (Disney historian Paul F. Anderson is working on this)

- Disney and Space (I am hoping to tackle that project very soon)

- The 1941 Disney studio strike

- Walt's later trips to Europe

The list goes on almost forever.

Other Books by Didier Ghez:

- They Drew as They Pleased: The Hidden Art of Disney's Golden Age (2015)

- Disney's Grand Tour: Walt and Roy's European Vacation, Summer 1935 (2013)

- Disneyland Paris: From Sketch to Reality (2002)

Didier Ghez has edited:

- Walt's People: Volume 15 (2014)

- Walt's People: Volume 14 (2014)

- Walt's People: Volume 13 (2013)

- Walt's People: Volume 12 (20xx)

- Walt's People: Volume 11 (20xx)

- Walt's People: Volume 10 (20xx)

- Walt's People: Volume 9 (20xx)

- Walt's People: Volume 8 (20xx)

- Walt's People: Volume 7 (20xx)

- Walt's People: Volume 6 (20xx)

- Walt's People: Volume 5 (20xx)

- Walt's People: Volume 4 (20xx)

- Walt's People: Volume 3 (2015)

- Walt's People: Volume 2 (2015)

- Walt's People: Volume 1 (2014)

- Life in the Mouse House: Memoir of a Disney Story Artist (2014)

- Inside the Whimsy Works: My Life with Walt Disney Productions (2014)

In this excerpt from Disney animator Jack Bradbury's autobiography, Jack remembers his tenuous start at Disney's as an inbetweener.

Old Disney studio on Hyperion. The first Monday after arriving, I hurried out to Hyperion Avenue on the east side of Hollywood, where the studio was located. There I was taken in to meet George Drake, the man in charge of the Inbetween Department and new trainees.

We had a little informal chat first, then sitting at an animation desk in his office, George flipped through an animated scene to show me how the progression of drawings gave the illusion of movement. This was fascinating, for I was now seeing just how it was done. George took out a couple of key drawings.

“These,” he said, “are called ‘extremes’. They are the important or key drawings in the scene. The animator creates the movement by drawing the character moving through the scene as prescribed by the director. His main key drawings are the extremes of the action. Then an assistant breaks it down to simple inbetweens, which are done in this department. That’s what you will be learning to do here.”

As he said this, he placed the two key drawings, numbers 43 and 47, on the two pegs that held the drawings in place. Turning on a light beneath, we could now see the bottom drawing through the top one. He then put a blank sheet of paper on the pegs over the other two. Then flipping the top two separately, he began to create a drawing that was half-way between the two. He again flipped the two top drawings separately to show me the bit of movement between the three drawings. “See how it works?” he said.

“Always leave the bottom drawing still, just flip the top two and do it constantly as you draw, to see just where to put the lines as you make the middle drawing, called an inbetween.”

He pointed to a little vertical line drawn in the corner which was divided in half, then in half, then in half again. Each division was numbered. The middle one between 43 and 47 was numbered 44, the next one dividing 44 and 47 was 45, and the final drawing between 45 and 47 was 46.

“You see,” George explained, “here the animator has indicated he wants the inbetweens done this certain way, which will slow the action into 47. Do you understand?” George smiled at me scratching my head. I didn’t quite get it, not until later. “Think you can do that?” he asked. I wasn’t at all sure, but I wasn’t going to admit it. “I’ll sure give it a good try.” I grinned not too confidently. He gave me an old scene from a past production, from which he’d removed all the inbetweens. Then he handed me a metal Eversharp pencil and a small box of long, thin HB leads.

From his office in the rear, he walked me through the large, well-lit inbetweener’s room of five or six rows of animation desks, each row having three or four inbetweeners cheerfully busy at their work. They seemed like a happy crew and glanced up, smiling as we walked by. In the front end of the big room was a row of four desks kept only for those “trying out”. I was the only one at present, but soon I’d see others come and go, most of whom would leave disappointed, never to return.

“There’s plenty of paper above you there on the shelf, Jack. So go to it. And if there’s anything you don’t understand, or if you have any questions, just come back and see me.” I thanked him and sat down to look at the scene on which I’d be making that so-important “tryout”. I tried holding it in one hand and flipping the pages with the other as George had done, but I was awkward and clumsy. I switched hands and got the same result.

Finally, I got so I could flip the pages well enough to see the action more clearly, and as I sat studying the movement, it suddenly occurred to me that this scene, created by one of the talented animators, had already been seen on the screen by millions of people. A little chill of excitement ran through me.

Placing the scene on the shelf, I took the first two extremes from the stack of drawings, number 1 and 5, and placed them on the pegs, then a blank sheet of paper on top of both. Then taking out a thin HB lead, I inserted it into the Eversharp and I was ready to go. No, not quite. As thin as the lead was, it still had a blunt point, so I took another sheet of paper and worked the point sharp. Now I was ready.

Trying to flip the two top drawings, as George had so easily done, was difficult to do. And there was no sense trying to draw the inbetween until I could flip the drawings well enough to see where to put the darn inbetween lines. For a long time I sat just trying to flip the two top drawings properly. Unable to perform this simple requirement right off, I felt like a clumsy dummy, never suspecting that everyone seated behind me in that big room had also probably gone through the same thing. I don’t know why, but I was positive they’d all been able to master this trick right away.

It took me a couple of days and a lot of wasted paper to get a decent start, but as I got into it, I began to see how many things you could do wrong on a simple inbetween. It is so easy to get the size of the head, or the hands, or the body of your inbetween character wrong. Yours might be smaller, larger, too thin, or somehow unlike the other two drawings. It is difficult to see at first, and being able to do inbetweens right comes only after working hard at it for quite some time.

Still sitting alone in “try-out” row, I could hear the other inbetweeners behind me working away happily, talking and singing as they banged out their drawings. I knew I could learn to do this and I wanted badly to become one of them.

Continued in "Walt's People: Volume 16"!

In an interview with Michael Broggie, Walt's personal secretary, Lucille Martin, talks about his moods, the only time he got angry with her (it involved Bob Hope), and other topics.

MB: People talked about Walt’s moods and tempers and things like that.

LM: I never saw it. In the office he was even keel. He got mad at me once, but it was the only time. It was on a Friday and everyone went home early on a Friday afternoon then, but not Walt. He would say, “Get so and so,” and I found out they left for the day. Then he’d say, “Get the next person,” and I’d say, “Left for the day.” “Somebody else.” “Left for the day.” And on it went. So I’d say, “Sorry, they left for the day,” and he’d say, “That’s okay, they’re working all the time. They’re creative and you just don’t turn that off. So it’s okay if they leave early, they’re working.” He never got mad at them and never got mad at either one of us, except that one time he got mad at me.

It was his last summer and he was really looking forward to this cruise in Alaska and all the children were going, and it was kind of unusual to get all the children together. I think Ron and Diane had six kids. They were going, and Bob Brown and Sharon, and Victoria who was a baby. She was, I think, nine months old. They flew up to Seattle and boarded the yacht. He called in every evening to get his messages and anything we needed him for.

There was this airline strike then, and Bob Hope chartered a yacht when Walt left. He was going to go fishing with some of his buddies and he called and said could he fly up to Seattle on the plane going to pick up Walt and his family. I asked Walt and he said, “Fine, no problem.” So I made arrangements with Bob and I asked the pilots what time Bob Hope and his buddies should be out at the flight office in order to be there at the time Walt specified to pick them up in Seattle. I think they were taking the boat from Canada to Seattle.

The night before they were due to be picked up, Bob Hope called the captain to see that everything was alright and it just so happened that Walt was in the cabin with the captain. So the captain said, “Walt’s right here.” So Bob asked to speak to him. He wasn’t prepared and didn’t know exactly what to say, so kiddingly he said, “This is great, we really appreciate you giving us this ride, because we can’t get a plane up, but why did you have to get us up so early?”

And Walt was upset and the next morning he called me and said, “Why did you make Bob Hope get up so early?” I said, “It was the time the pilots said they had to leave in order to pick you up at that time.” He said, “We could have changed our time.” But I know with all those children and with Mrs. Disney waiting, just because Bob Hope didn’t want to get up early, and a nine-month-old baby, there’s no way I should have done any different. I’ve always been like that. If I know I’m right, it doesn’t bother me. I’m very apologetic if I’m wrong. But he came in and walked right past my desk.

MB: So you knew something was up. What was his usual greeting?

LM: “Good Morning,” and “Get me a cup of coffee.” But it didn’t bother me. I thought, “He’ll get over it. I know I did right. He’ll get over it.” But he did it for about two days. Didn’t call my intercom to make any phone calls and then it was all over. But it really didn’t bother me. Tommie said about the girl before me, who was there just a couple of weeks, that if he said anything cross to her that she would cry. Tommie would say, “You have to go someplace else and cry. You can’t sit at this desk and cry.” But it didn’t bother me a bit, and he was always so nice, and in a couple of days it was over and forgotten about. I know I asked Diane and Sharon, “What did he say about that?” They said he never mentioned it, never said a word. He knew he was wrong, and he never complained about it or said a word.

We were always asked to find a gift for Mrs. Disney, and I remember Tommie was on the phone trying to find a piece of jewelry or a watch or a new perfume and suggest it to him, and he said, “No.” After a couple of days he came in one morning and said, “I got it. Send her…” I can’t remember what the anniversary was. It was like thirty-seven or thirty-nine red roses. He said “And say, ‘you lucky girl’.” Mrs. Disney didn’t remember that, but I remembered it. I was so touched by it. I thought it was pretty special. He was very pleased about it.

MB: Did you have anything to do with having the hat bronzed? It was given on Valentine’s Day one year. It was the hat that Lillian had flipped right into the bullring when they were in Mexico.

LM: Oh no, that must have been before my time.

MB: She hated that hat. We have one of them in the barn on display. It was a favorite hat that he liked to wear. So she pulled it off his head and flipped it right into the bullring, hoping the bull would trample and ruin it, so she wouldn’t have to look at him in that silly hat.

LM: She was a gutsy lady.

MB: One of the toreadors who retrieved it brought it back over and handed it to him, so he brushed it off and put it back on, and as a gift for Valentine’s Day he had the crown shaped as a heart and had it bronzed on a plaque, and it was still hanging on a wall in the pool house at Carolwood. When I used to go and visit Mrs. Disney, there it was right on the wall.

LM: It wasn’t there when I used to go in.

MB: The children, did they ever come around the offices?

LM: Yes, they did. I can’t remember an occasion, but they did come in and out. I can remember, I think it was when Patrick was born, and he was so eager to get out to the hospital to see Diane and his new grandson.

MB: He was very pleased when Walter was born: finally a son. He was beginning to wonder, because he wasn’t happy the first one wasn’t named after him. [Christopher was the first grandson.] So there were a couple of girls who came along after, then finally Walt, and he had these cigars made up.

LM: I remember seeing those cigars.

MB: He passed them all around. He was very proud. My father didn’t smoke, but he had a collection of cigars that had been given to him, and they were on this little gadget on the back of his desk. I remember, when I was kid, I would look at the cigars because they had this writing on them. One of them was that “Walter” cigar.

LM: And then he got two more boys, because it was Walter, Ronnie, and Patrick. He was gone when Patrick was born, so it was Ronnie he visited. [Ronald was born on October 9, 1963, and Patrick onNovember 19, 1967.] I went to work for Ron [Miller] after. I stayed on and wrote “Thank You” letters for Mrs. Disney. We had a lot of those to send out and we answered every one of them. Mrs. Disney and Diane answered them, and I stayed on another year in the office. I don’t remember when I went on to Ron Miller’s office. So I was in Walt’s office and Ron was just a vice president, and I went to work with him and then he was made president and we went back to Walt’s office. When Michael Eisner came in, he was in Walt’s office.

MB: Didn’t you work with Card Walker, too?

LM: No, I never went to work for him. I went from Walt to Ron to Michael.

MB: Donn Tatum was in there, too, with Card.

LM: Donn Tatum had Mary Mullen that worked for him.

MB: Did they all take Walt’s office at one time or another?

LM: No. Just Walt and Ron and Michael had Walt’s office.

MB: As I understand, for a long time the offices were just kept closed and all the furniture was there and they finally took it all out and took it down to Disneyland.

LM: What happened was they closed his office and Ron didn’t want to go, as he thought it was a bit presumptuous to go to Walt’s office. But Card Walker talked him into it when he became president. So they closed it for a while and then the Archives went in there and then when Ron became president, Card talked him into moving back in it. When Michael came in, he came right into it, too.

MB: What was the change in atmosphere when Michael and Frank [Wells] came aboard?

LM: Michael was trying very hard to be the thing. Two assistants came with him from Paramount, but didn’t stay very long. They always called him “Mr. Eisner”, and after I finally got “Walt” down, I was calling him “Michael”. And, you know, it was “Ron” [for Ron Miller]. Michael said, “I’m not so sure I like to be called by my first name,” because the other girls called him “Mr. Eisner”. I said Walt went by “Walt” and I think I showed him my little picture and he said, “Well, let’s go along with it.” At that time I didn’t know what was going to happen to me. Michael came in with two girls, so I went over to Universal and applied for a job with Jules Stein. He was a good friend of Walt’s and he had been in and out, and he knew me. So I went over thinking, “I better get a job,” because these two girls were going to replace me. It was about at that time there was an employees’ recognition party, and Michael and Frank Wells passed out the awards and Frank was talking about all the assets the company had and how they were going to have to get used to the parks and this and that, and Michael got up and said, “and I got Lucille,” and everybody clapped. So that was when I knew that I had a job.

Continued in "Walt's People: Volume 16"!

About Theme Park Press

Theme Park Press is the world's leading independent publisher of books about the Disney company, its history, its films and animation, and its theme parks. We make the happiest books on earth!

Our catalog includes guidebooks, memoirs, fiction, popular history, scholarly works, family favorites, and many other titles written by Disney Legends, Disney animators and artists, Mouseketeers, Cast Members, historians, academics, executives, prominent bloggers, and talented first-time authors.

We love chatting about what we do: drop us a line, any time.

Theme Park Press Books

The Unauthorized Story of Walt Disney's Haunted Mansion The Ride Delegate 501 Ways to Make the Most of Your Walt Disney World Vacation The Cotton Candy Road Trip The Wonderful World of Customer Service at Disney Disney Destinies Disney Melodies The Happiest Workplace on Earth Storm over the Bay A Historical Tour of Walt Disney World: Volume 1 Mouse in Transition Mouseketeers Down Under Murder in the Magic Kingdom Walt Disney and the Promise of Progress City Service with Character Son of Faster Cheaper A Tale of Two Resorts I Saw Ariel Do a Keg Stand The Adventures of Young Walt Disney Death in the Tragic Kingdom Two Girls and a Mouse Tale Ears & Bubbles The Easy Guide 2015 Who's the Leader of the Club? Disney's Hollywood Studios Funny Animals Life in the Mouse House The Book of Mouse Disney's Grand Tour The Accidental Mouseketeer The Vault of Walt: Volume 1 The Vault of Walt: Volume 2 The Vault of Walt: Volume 3 Who's Afraid of the Song of the South? Amber Earns Her Ears Ema Earns Her Ears Sara Earns Her Ears Katie Earns Her Ears Brittany Earns Her Ears Walt's People: Volume 1 Walt's People: Volume 2 Walt's People: Volume 13 Walt's People: Volume 14 Walt's People: Volume 15

Write for Theme Park Press

We're always in the market for new authors with great ideas. Or great authors with new ideas. Whichever type of author you are, we'd be happy to discuss your book. Before you contact us, however, please make sure you can answer "yes" to these threshold questions:

Is It Right for Us?

We specialize in books that have some connection to Disney or theme parks. Disney, of course, has become a broad topic, and encompasses not just theme parks and films but comic books, animation, and a big chunk of pop culture. Your book should fit into one (or more) of those broad categories.

Is It Going to Make Money?

There's never a guarantee that any book will make money, but certain types of books are less likely to do so than others. They include: hardcovers, books with color photos, and books that go on forever ("forever" as in 400+ pages). We won't automatically turn down these types of books, but you'll have to be a really good salesman to convince us.

Are You Great to Work With?

Writing books and publishing books should be fun. The last thing you want, and the last thing we want, is a contentious relationship. We work with authors who share our philosophy of no drama and zero attitude, and the desire for a respectful, realistic, mutually beneficial partnership.

If you said "yes" three times, please step inside.