- Visit the Imagineering Graveyard

- Now Sailing: "Skipper Stories" - Tales from the Jungle Cruise

- Coming Soon: The biography of Disney animator Jack Hannah

- Coming Soon: A Haunted Mansion anthology

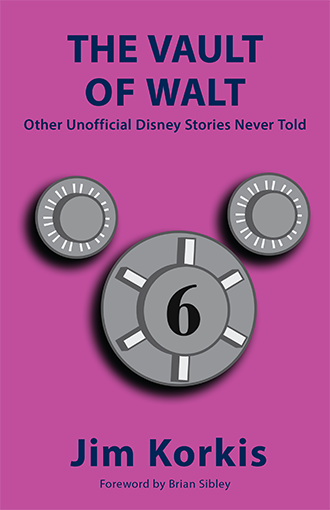

The Vault of Walt: Volume 6

Other Unofficial Disney Stories Never Told

by Jim Korkis | Release Date: December 16, 2017 | Availability: Print, Kindle

Disney History at Its Best

No one knows Disney history, or tells it better, than Jim Korkis, and he's back with a new set of 20 stories from his Vault of Walt. Whether it's Disney films, Disney theme parks, or Walt himself, Jim's stories will charm and delight Disney fans of all ages.

The best-selling Vault of Walt series has brought serious, but fun, Disney history to tens of thousands of readers. Now in its fifth volume, the series features former Disney cast member and master storyteller Jim Korkis' home-spun, entertaining tales, from the early years of Walt Disney to the present.

Step inside the vault with Jim to hear about:

- The story of Walt Disney's first studio, Laugh-O-gram

- Dinosaurs in the Disney theme parks

- The little-known People and Places short film series

- Walt's connections with Charlie Chaplin, Abraham Lincoln, and Bob Clampett

- The story of Duffy the Bear

Discover these and many other new tales of Disney history, as only Jim Korkis can tell them, in The Vault of Walt: Volume 6.

Then be sure to check out ALL the volumes in THE VAULT OF WALT!

Table of Contents

Foreword

Introduction

Part One: Walt Disney Stories

The Charlie Chaplin Connection

The Abraham Lincoln Connection

Roy O. Disney Remembers Walt

Walt Never Said It

The Canadian Connection

Part Two: Disney Film Stories

Seal Island: The First True-Life Adventure

People and Places: The Forgotten Series

The Laugh-O-gram Story

The Love Bug Story

The Orange Bird Film

Part Three: Disney Park Stories

The Disney Hub

Disneyland 1957

Disneyland 1967

Theme Park Dinosaurs

Epcot Center Opening

Part Four: Other Disney Stories

The Bob Clampett Connection

The Disney Pigeons

The Snow White Lawsuit

Duffy the Bear

Remembering Roy E. Disney

Foreword

I have something to get off my chest: despite having spent a disproportionate part of my life collecting and writing about all things Disney: my earliest encounter with the Mousetro’s work proved deeply traumatic for me and acutely embarrassing for my parents.

What ended as a nightmare had begun as a treat for my fourth birthday: a visit to a now-long-gone British institution, the News Theatre on London’s Waterloo Station. Open daily, from 9 a.m. to 11 p.m., the News Theatre screened a continuous program of newsreels, comedy one-reelers, and cartoons.

On this particular day, the bill featured the vintage 1938 Disney short, Brave Little Tailor, in which Mickey Mouse, in the title role, tackles an enormous giant in order to win the hand of the Princess Minnie.

At a crucial point in this drama, Mickey hides in a cart laden with pumpkins and, when the giant grabs a handful as a snack, Mickey finds himself being hurled into the giant’s mouth. Dodging the pumpkins as they hurtle by him like bowling balls, he only avoids being swallowed by hanging onto the giant’s uvular.

These antics were, naturally, greeted with hilarity by every other youngster in the cinema—but not, unfortunately, by me! Terrified at the mouse-threatening scenario unfolding before me in the dark, I screamed and screamed until my humiliated parents bundled me out of the theatre and rushed me off to the nearest café to pacify me with tea and buns.

I make this confession as it may help to explain the fixation with Disney that has obsessed me virtually ever since that harrowing day. Without that shock to my young system, that jolt to my nascent psyche, would I have co-authored several books on Disney topics (from Mickey Mouse and Snow White to Mary Poppins) or made several dozen hours of radio programmes for the BBC about Uncle Walt, his company and movies? Probably not.

One of the by-products of this career (of which I’ve only provided the sketchiest of detail since I’m taking up space in somebody else’s book on Disney) is the occasional invitation to write a foreword such as the one I’m just about to get down to writing here.

Within the annals of cinema history there is a small but growing coterie of dedicated scribes who are dubbed Disney historians. There is an urgent imperative to chronicle the life and times of Walt Disney and the achievements of his studio because it is the story of many people, most of whose contributions have only begun to be recorded in the past 50 years since the death of the man whose internationally recognized signature came to represent the combined talents of an army of artists, writers, musicians, and technicians.

Some of us of a certain age can still recall when there were scarcely more than a handful of books about the art and industry of Disney. Today there are shelf-loads of such books—representing a wide range of approaches from the academic and authoritative via the critical to the anodyne and scurrilous.

Nevertheless, there are still first-hand recollections needing to be recorded and new chapters of the story waiting to be written—not to mention the tedious task of correcting inaccuracies and remedying misconceptions.

One of the most prolific of these Disney historians is the indefatigable Jim Korkis (“At last!” you say, “This foreword is finally getting to the point!”) whose Disney vault you are about to enter.

I first met the vault keeper sixteen years ago, on December 5, 2001 (Walt’s hundredth birthday). We were in the VIP lounge of the Norway pavilion in Epcot and, whilst I no longer recall the reason for that choice of venue, I mention it since the fact that Epcot has a Norway VIP lounge will be, for some, an irresistible piece of Disney park trivia eagerly learned.

After signing a book of mine for Jim (despite my protestations that the only valuable copies are the unsigned ones), he gave me a cracking interview for one of my radio shows as a result of which I immediately had the measure of Jim’s talent: he was, like Shakespeare’s clown Autolycus, “a snapper-up of unconsidered trifles,” by which I mean that he collected a wealth of information that others had overlooked or disregarded and stored it away in his vast memory bank—or, you could say, vault!

Korkis books are always filled with these discoveries, fashioned together so as to create a series of diverse narratives of varying—but satisfyingly appropriate—length where the whole is always greater than the sum of the parts.

Jim is a born teller of tales, able to engage, excite, intrigue, and amuse us with stories that reveal not just his talent for research but also his gift of infectious enthusiasm. If something fascinates Korkis, he will make sure we share his fascination.

This is not surprising since he has met and talked with dozens of Disney animators and those theme park wizards known as “Imagineers” and has been writing about them and their genius boss for three-and-a-half decades.

Looking through the table of contents I can’t quite decide where I’ll start: maybe with the stories about Walt’s enthrallment with Abe Lincoln and Charlie Chaplin; or, perhaps, with the appreciation of Disney park dinosaurs; or, possibly, with the articles on the Oscar-winning documentary Seal Island, and the zany comedy that introduced the world to Car 53—Herbie, the Love Bug. Wherever I start, I can guarantee to be riveted and end up knowing immeasurably more than when I started.

In view of the distressing recollection with which I began this foreword, I was wondering if an essay on Disney giants might be on offer; but it really doesn’t matter because Jim can always add it to the possible contents list for his next foray into the Disney vault; meanwhile (since I’ve detained you far too long already), you can start enjoying this one.

Right, then! Off you go…

Introduction

Where do the stories come from? That was the title of an episode of ABC’s Disneyland weekly television show that originally aired on April 4,1956.

Walt said at the beginning of that show:

We have often been asked where do we get the ideas for our stories. Potential story ideas exist all around us and our story men have been trained to closely observe every day happenings with the thought of twisting a common occurrence into a story.

During the show, Walt explained how books, songs, personal experiences, and hobbies could springboard the development of an entertaining story.

I’ve often been asked a similar question about the stories that appear in The Vault of Walt series of books. Sometimes these books are the only place where a reader can find information about Walt Disney’s involvement in the DeMolay organization or the educational films made featuring Figment or Walt’s mother’s recipe for apple pie.

How do I know all these things if they don’t appear elsewhere? For nearly forty years I have been writing stories about Disney history that have been shared in a variety of media. At one point, I even worked for the Disney company and had access to people and material that others did not and wrote articles and did historical presentations for the company.

Growing up in the Los Angeles area near the Disney studio, I had the opportunity to personally interview animators, Imagineers, executives, theme park cast members, Disney family, and others who knew and worked with Walt. I also was able to attend countless events where people shared their Disney stories, and got to interact with them afterwards.

I spent time and money acquiring a personal library of documents, from vintage newspaper and magazine clippings to private letters, publicity material, and obscure books. All of this was my foundation to begin writing. However, just because someone says something or it appears in print does not make it true.

Sometimes people had faulty memories, only saw their part of the project, had a personal agenda they wanted to assert, wanted to promote something aggressively, simply repeated stories that “everyone knows” but no one ever really checked, or other things that obstruct the truth.

So, while having this rich foundation of information to begin work, it was only just the beginning. The hardest work was to try to verify it through several independent sources.

When more and more people began writing about Disney history, it quickly became apparent that they were concentrating on the same familiar stories and sometimes just repeating falsehoods that had previously appeared somewhere without doing any original research to confirm or debunk. Even today those falsehoods often crop up with alarming regularity.

No one seemed to be writing about the stories that I knew. I began to feel an obligation to share the stories that had been so generously shared with me, especially from people who were no longer around to share them with others.

When I wrote the first volume in this series, I fully believed there might be enough interest in these out-of-the-ordinary stories to sell a few copies. However, those stories proved so popular that right now I am writing this introduction to the sixth volume in the series and preparing a file folder of material for a possible seventh.

Some of the stories that follow are particular favorites of mine and have been greatly enhanced with new discoveries I and others have made over recent years. For now, there seems still to be some interesting stories left to share.

As always, I hope you enjoy these stories and will share them with others.

Jim Korkis

Jim Korkis is an internationally respected Disney historian who has written hundreds of articles and twenty books about all things Disney over the last forty years. The Vault of Walt series began in 2012 and continues with a new edition every year.

Jim grew up in Glendale, California, where he was able to meet and interview Walt’s original team of animators and Imagineers. In 1995, he relocated to Orlando, Florida, where he worked for Walt Disney World in a variety of capacities, including Entertainment, Animation, Disney Institute, Disney University, College and International Programs, Disney Cruise Line, Disney Design Group, Marketing.

His original research on Disney history has been used often by the Disney company as well as other organizations such as the Walt Disney Family Museum.

Jim is not currently an employee of the Disney company.

Several websites currently regularly feature Jim’s articles about Disney history, and he is a frequent guest on multiple podcasts.

Young Walt Disney idolized Charlie Chaplin, the "Little Tramp", and routinely won cash prizes at Chaplin look-alike contests. Later, Walt met Chaplin, and made no secret that aspects of Mickey Mouse were based on Chaplin's Tramp character.

When Walt arrived in Hollywood in 1923, he purposely made sure that when he walked to the employment office looking for work that he lingered for a while on LaBrea where the Chaplin movie studio was located in the hopes of catching a glimpse of his silent-screen hero. In an interview, Walt admitted that if he had seen his idol, he would have been too awestruck to say anything to him.

Chaplin had built the studio in 1917 to resemble an old English village with a Tudor mansion façade and trimmed landscaping. It still stands today, although half the size of its original five acres.

When Chaplin left the U.S. in 1952, the studio was taken over by a variety of owners including CBS, which filmed shows like The Adventures of Superman there, and it later became the headquarters for A&M Records under Herb Alpert. Finally, the studio was purchased by Jim Henson Productions and as a fitting tribute a statue was installed at the entrance of Kermit the Frog dressed as the Little Tramp.

Walt and Chaplin were formally introduced around 1930 when Mickey Mouse had became a success.

Walt told writer Pete Martin in June 1956:

Charlie was a great friend. He was an admirer and it was mutual admiration because way back in my life, I used to impersonate Charlie Chaplin. I won a lot of prizes in theaters. I did it when I was going to school. I did it in theaters on amateur night. I was movie struck. I was stage struck.

One of the things I did was Chaplin. I had all his tricks down. I never missed a Chaplin picture. A neighbor boy—he’s over at the studio with me now—together we had a little act. He was the count. He was the straight man with me as Chaplin. Then we would go to these amateur things. We’d put on our little act.

We always got a little more applause than someone else imitating Chaplin because we were younger and there was a team of us. We won a lot of prizes. We’d get a couple of bucks or something. But it was more the fun of doing it, you see? Chaplin was my idol. His comedy, the subtleties of it and things like that I always admired.

Chaplin admired Walt and Mickey Mouse as well. On October 15, 1933, there was a Writers’ Club dinner in Hollywood where Walt was the guest of honor. Chaplin attended and sat at the same table as Walt. To amuse the animator, Chaplin got up and did a little pantomime including his famous Little Tramp walk. American humorist Will Rogers, a friend of Walt’s who also attended the event, wrote:

We were all down to a mighty fine dinner they gave to Walter Disney. He is the sire and dam of that gift to the world, Mickey Mouse. Now, if there wasent (sic) two geniuses at one table, Disney and Charley (sic) Chaplin. One took a derby hat and a pair of big shoes and captured the laughs of the world, and the other one took a lead pencil and a mouse, and he has the whole world crawling in a rat hole, if necessary, just to see the antics of those rodents.

But there was more than shoes and pencils and derby hats and drawing boards there. Both had a God-given gift of human nature. Well, of course, they base it all on psychology of some kind and breed, but it’s something human inside these two ducks that even psychology hasent (sic) a name for.

In the January 20, 1934, issue of the New Yorker there is a cartoon by “Alain” where a phony sophisticate is venting to his entranced girlfriend: “All you hear is Mickey Mouse, Mickey Mouse, Mickey Mouse! It’s as though Chaplin had never lived.”

At the 1932 Academy Award ceremonies, Walt received the second special award in the academy’s five year history “for the creation of Mickey Mouse.” The previous special award recipient in 1929, Charlie Chaplin, was supposed to present Disney’s award, but elected at the last minute to stay home.

As Alva Johnston wrote in the July 1934 issue of Woman’s Home Companion:

Charlie Chaplin and Mickey Mouse are the only two universal characters that have ever existed. The greatest kings and conquerors, gods and devils have by comparison been local celebrities. Mickey’s domain is today even more extensive than Chaplin’s. Charlie’s mustache, hat, pants, shoes, and cane belong to Western civilization and make him a foreigner in some regions. Mickey Mouse is not a foreigner in any part of the world.

By the mid-1930s, Mickey had indeed started to eclipse Chaplin’s fame and popularity, yet during the early 1930s, writers delighted in connecting the two comedy legends because of several obvious similarities.

Both Mickey and Chaplin uniquely entertained a broad public audience as well as the intellectual elite and did so primarily through their actions and reactions rather than with dialog. Both spawned extensive merchandise empires as well, unmatched by other Hollywood stars.

Walt Disney himself loved to foster the impression that the two icons had a similar ancestry.

In The American Magazine for March 1931, he described Mickey’s creation:

I can’t say just how the idea came. We felt that the public—especially children—like animals that are “cute” and little. I think we were rather indebted to Charlie Chaplin for the idea. We wanted something appealing and we thought of a tiny bit of a mouse that would have something of the wistfulness of Chaplin ... a little fellow trying to do the best he could.

Continued in "The Vault of Walt: Volume 6"!

The dinosaurs in the Disney parks, with an exception or two, will not be devouring guests in the middle of Liberty Square. Theme park saurians tend toward the scientific, not the savage.

The real reason dinosaurs are in the Universe of Energy pavilion is not because of their tentative connection with oil but because of Walt Disney’s fascination with making dinosaurs “live again” for modern audiences.

It began with the animated feature Fantasia (1940). Walt said he wanted the “Rite of Spring” segment focusing on the reign and extinction of the dinosaurs to look “as though the studio had sent an expedition back to earth sixty million years ago.” The studio contacted museums and world-famous authorities like Roy Chapman Andrews, Julian Huxley, Barnum Brown, and Edwin P. Hubble with detailed requests for information.

Disney animators were confronted with the challenge of how to draw a dinosaur in movement. The director told the puzzled animators to “just draw a 12-story building in perspective, then convert it into a dinosaur and animate it.”

Walt told the animators: “Don’t make them cute animals. Make them real”. To help achieve a sense of size, the camera level was kept low so audiences were always looking up at the massive animals.

Paleontologists had reconstructed skeletons of the extinct giants, but how does a Stegosaurus tail move and what was the skin texture and skin color like? Disney animators had to use their knowledge of balance, weight, and color, as well as their experience drawing real animals, and were able to create a reasonable approximation that garnered accolades in the scientific community.

Pterodactyls took flight while a herd of brontosauruses quietly grazed in a lake in the film, Those images were later translated into three dimension at the Disney theme parks.

Time magazine reported:

The New York Academy of Science asked for a private showing because they thought [Fantasia’s] dinosaurs better science than whole museum loads of fossils and taxidermy.

As early as the 1950s, an edited version of just the dinosaur segment with narration was released to schools to be used in science classes and other organizations through Disney Educational Media under the title A World Is Born. Stephen Jay Gould, who went on to become one of the century’s great evolutionary biologists, claimed that he became enthused with dinosaurs as a child thanks to seeing this film.

One of the most memorable scenes included a climactic battle between a stegosaurus and a vicious, red-eyed tyrannosaurus rex that could never have happened since those animals lived in different eras, but it was highly memorable and dramatic. It was such an iconic scene that it became an integral part of both Disneyland and Walt Disney World.

Walt’s next step into the prehistoric world was roughly two decades later: actual gigantic moving dinosaurs using Disney’s then-new technology of audio-animatronics. The idea was to do a more authentic and impressive dinosaur show than Sinclair’s Dinoland that proved so popular at the New York World’s Fair that it went on as a traveling exhibit and spawned souvenir toys.

Continued in "The Vault of Walt: Volume 6"!

About Theme Park Press

Theme Park Press is the world's leading independent publisher of books about the Disney company, its history, its films and animation, and its theme parks. We make the happiest books on earth!

Our catalog includes guidebooks, memoirs, fiction, popular history, scholarly works, family favorites, and many other titles written by Disney Legends, Disney animators and artists, Mouseketeers, Cast Members, historians, academics, executives, prominent bloggers, and talented first-time authors.

We love chatting about what we do: drop us a line, any time.

Theme Park Press Books

The Unauthorized Story of Walt Disney's Haunted Mansion The Ride Delegate 501 Ways to Make the Most of Your Walt Disney World Vacation The Cotton Candy Road Trip The Wonderful World of Customer Service at Disney Disney Destinies Disney Melodies The Happiest Workplace on Earth Storm over the Bay A Historical Tour of Walt Disney World: Volume 1 Mouse in Transition Mouseketeers Down Under Murder in the Magic Kingdom Walt Disney and the Promise of Progress City Service with Character Son of Faster Cheaper A Tale of Two Resorts I Saw Ariel Do a Keg Stand The Adventures of Young Walt Disney Death in the Tragic Kingdom Two Girls and a Mouse Tale Ears & Bubbles The Easy Guide 2015 Who's the Leader of the Club? Disney's Hollywood Studios Funny Animals Life in the Mouse House The Book of Mouse Disney's Grand Tour The Accidental Mouseketeer The Vault of Walt: Volume 1 The Vault of Walt: Volume 2 The Vault of Walt: Volume 3 Who's Afraid of the Song of the South? Amber Earns Her Ears Ema Earns Her Ears Sara Earns Her Ears Katie Earns Her Ears Brittany Earns Her Ears Walt's People: Volume 1 Walt's People: Volume 2 Walt's People: Volume 13 Walt's People: Volume 14 Walt's People: Volume 15

Write for Theme Park Press

We're always in the market for new authors with great ideas. Or great authors with new ideas. Whichever type of author you are, we'd be happy to discuss your book. Before you contact us, however, please make sure you can answer "yes" to these threshold questions:

Is It Right for Us?

We specialize in books that have some connection to Disney or theme parks. Disney, of course, has become a broad topic, and encompasses not just theme parks and films but comic books, animation, and a big chunk of pop culture. Your book should fit into one (or more) of those broad categories.

Is It Going to Make Money?

There's never a guarantee that any book will make money, but certain types of books are less likely to do so than others. They include: hardcovers, books with color photos, and books that go on forever ("forever" as in 400+ pages). We won't automatically turn down these types of books, but you'll have to be a really good salesman to convince us.

Are You Great to Work With?

Writing books and publishing books should be fun. The last thing you want, and the last thing we want, is a contentious relationship. We work with authors who share our philosophy of no drama and zero attitude, and the desire for a respectful, realistic, mutually beneficial partnership.

If you said "yes" three times, please step inside.