- Visit the Imagineering Graveyard

- Now Sailing: "Skipper Stories" - Tales from the Jungle Cruise

- Coming Soon: The biography of Disney animator Jack Hannah

- Coming Soon: A Haunted Mansion anthology

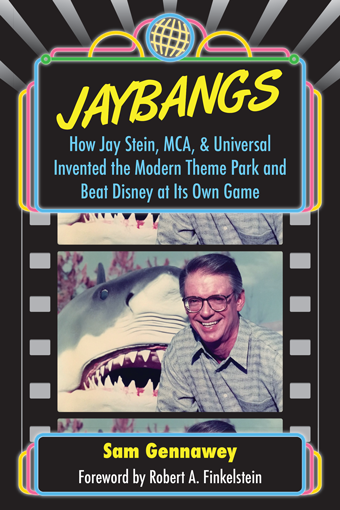

JayBangs

How Jay Stein, MCA, & Universal Invented the Modern Theme Park and Beat Disney at Its Own Game

by Sam Gennawey | Release Date: October 16, 2016 | Availability: Print, Kindle

Jay Stein Builds a Better Mousetrap

After years of sitting fat and happy atop the theme park totem pole, Mickey Mouse discovered a big cat in his backyard named Jay Stein. Against stiff odds, corporate politics, and fierce opposition from Michael Eisner's Disney, Jay Stein founded Universal Studios Florida. This is how he did it.

Starting in the mailroom of MCA (now NBCUniversal), where his duties included delivering messages to stars like Alfred Hitchcock and Ronald Reagan, Jay Stein soon found himself in charge of the Universal Studio Tour, reporting directly to MCA chairman Lew Wasserman. He became a keen observer of what Walt Disney had accomplished in Disneyland—and how one day he might do even better.

That day came when Wasserman gave Jay the go-ahead to build a Universal theme park in Orlando, Florida. With help from Steven Spielberg, Jay got to work, in Jay style: no excuses, no retreats, no failures. Despite Disney's relentless attempts to sabotage the project, and ruinous infighting among members of his own team, Jay did not give up.

When the new theme park opened in 1990, it was full of Jay's patented "JayBangs"—rides and attractions that stunned, shocked, and surprised guests, dousing them with water, blasting them with air, heat, or cold, and giving them what the Disney parks of that time lacked: fear and visceral delight.

It was beating Michael Eisner at his own game. It was catching Mickey in a trap he couldn't aw-shucks his way out of. It was Jay Stein's triumph. But the man who went from delivering messages to building theme parks wasn't done yet...

Table of Contents

Foreword

Introduction

Chapter 1: Becoming an MCA Man

Chapter 2: Universal Studios Tour

Chapter 3: The National Parks

Chapter 4: On the Hunt

Chapter 5: Universal Studios Florida: Take One

Chapter 6: Universal Studios Florida: Take Two

Chapter 7: Universal Studios Hollywood

Chapter 8: Cartoon World

Chapter 9: That’s a Wrap

Epilogue

Appendix

Foreword

I received my undergraduate degree from MCA, Jay Stein in particular; my post graduate from Mickey Rudin, a prominent entertainment lawyer; and an advanced degree from Jerry Weintraub. A finer education is unimaginable.

But for Jay Stein and MCA, both Mickey and the presidency of Jerry’s Management III and Concerts West and all that followed representing Frank Sinatra, Gregory Peck, Norman Lear, Groucho Marx, the Cary Grant estate, and others, and my running my own entrepreneurial business, would have been impossible. You see, Jay, besides his mentoring, arranged (after my graduation from UCLA and working four years for the Universal Studio Tour) for MCA to pay the tuition for me to go to Georgetown Law School in return for my agreeing to come back to MCA for three years after graduating. It is a rare privilege to be a part of introducing the public to this remarkable man.

In 1965, Mike Ovitz and I were roommates in college; we learned from Herb Steinberg that Universal Studios was hiring college students for summer jobs giving tours of the studio.

Tickets for the tour were $2.50. The tour started from a makeshift facility at the front lot. Cliff Walker was the operations manager and the face of the tour, as far as we were concerned. Cliff lived and breathed outdoor recreation and had his finger on the pulse of managing and understanding young adults. Jules Stein, Lew Wasserman, and Al Dorskind were seen at the tour from time to time, but the operation was an annoyance to the studio. We were forbidden from identifying Cary Grant if we observed him on the lot or from going to an actual filming location.

In time, we were told of plans to expand the tour and open the upper lot, and eventually heard about this “relative” of Jules Stein who was going to be involved with the Tour. This is my first recollection of the name Jay Stein; I guess that was 1967. The upper lot opened, with the stunt show, the make-up show, the Tower of London set, souvenir shops, and food service—nice but certainly not Disney standards.

Guests parked in the new upper lot parking and were directed to kiosks to purchase their tickets before entering the lobby area to board the tram. The tour was a success and attracting near capacity attendance. By this time I was a tour guide foreman who would often double on the turnstile taking tickets. Who was the man in the suit that stood for hours in the lobby just observing and observing what was happening and once in a while whispering in Cliff Walker’s ear? This was my first visual introduction to Jay Stein, the new “tower” person responsible for the tour. (The whispering soon stopped). Jay was laser focused and you could practically see the gears of his mind working. While Cliff and Barry Upson were very engaging with all of the employees, Jay followed a careful chain of command, at least at first. You could feel Cliff musing how this “suit” from the tower was going to contribute to his outdoor entertainment domain.

The most important part of the “ticket-taking” job description became the hourly count. Jay, from his new perch in the tower, appeared to be myopically fixated on the count. What the hell difference did it make if the count was one thousand an hour or six hundred—business was good, and people still had to wait too long in line after they passed the turnstile (especially during the summer months). At that time I was not privy to Jay’s equal fixation with every other aspect of the tour, its minuet of numbers and margins. Lesson: numbers are critical. Untold additional business gems are revealed in Sam Gennawey’s narrative of the MCA/Stein take-no-prisoners winning business acumen.

Jay’s “suit/tower style” morphed, somewhat, after he had absorbed all of the operational details of the tour. He would on occasion drop in after the operating day was over to Cliff’s office where Cliff and the department heads would participate in a nightly review of the day’s and upcoming events with a cocktail, or maybe two. In hindsight, I think it was these off-the-clock but on-the-record gatherings that created the foundation of loyalty and camaraderie with Jay, even when he could be as demanding and speak at decibel levels above OSHA standards.

I became an assistant operations manager of the tour while attending UCLA. The tour was open on the weekend and UCLA was on the quarter system, so I could go to school Tuesday and Thursday and work full-time at the studio the rest of the week and weekends. Jay, Dorskind, and sometimes Wasserman would come up to the tour on weekends and I developed somewhat of a relationship with each of them, in particular, Jay.

At the time I was graduating from UCLA (1969), MCA had just started Landmark Services in Washington, D.C. So not only was MCA going to pay for my law school, but Jay arranged with Tom Mack (a tour guide when I first started and another recipient of Jay’s stewardship, now running the operation in Washington) for me to work at Landmark on the weekends.

Upon graduating law school, Jay placed me in an office on the 14th floor around the corner from his palatial office and next to Taft Schreiber’s. While I loved the law, Jay had instilled in me a passion for business.

It was now that my relationship with Jay became even closer and that I studied and observed, first hand, his amazing executive prowess. The tour, while very successful, was still in its adolescence. While I had some line responsibility, I attended almost all of Jay’s meetings. Jay was a circling lion looking for new opportunities and ways to constantly improve the tour. Most importantly, he was seeking to continually introduce new elements that he could promote and advertise. I was witness to Jay’s merciless grilling of the department heads on the numbers and the assumptions. Why didn’t that fucking thing work? Under no circumstances was Jay going to get positioned with Wasserman or Sheinberg in not being able to answer any question or have proposed or implemented a solution before the question was asked.

Jay’s timelines were as demanding as his questioning. There was no moderation to his priorities of items; everything, everything was due yesterday. I recall that Jay’s first wife had to have the water running in the bathroom at the time he got home so that he would not have to wait for the water to get hot to wash his hands. (You better not be playing in a slow foursome in front of Jay.)

I worked closely with Jay on the Amphitheatre, Yosemite, the counter-culture plans for the Real Estate, a Tivoli Garden concept for the upper lot, exploring an acquisition of Mammoth, Squaw Valley, developing a theme restaurant based upon the Knights of the Round Table, and many of the other early projects that Sam artfully explores. Lesson: one-of-a-kind attractions with exclusivity and significant barriers to entry will serve you well.

Sam reveals the never-before-known depths of Jay’s competitive spirit in making sure the Amphitheatre was a success and that the Greek was going to get the second choice acts for their summer season.

It was during the first year of the Amphitheatre that Jay and I first met Jerry Weintraub, John Denver’s manager. Jerry became a friend of Jay’s and was a participant in a weekly tennis game at Jules Stein’s house in Beverly Hills. We had to sweep the court before we could play, until Jerry got a house with his own court. Sam goes behind-the-scenes of the relationship between Jerry and Jay. Jay was one of the last people to be with Jerry before his sudden death last year.

By 1975, I had worked at MCA for three years and Jerry asked me to come to work for him. I told Jerry that in leaving MCA I really would like to practice law. Jerry arranged an interview with Mickey Rudin, the attorney who represented Jerry and Frank Sinatra. One of my missions while working with Mickey, out of loyalty to MCA and Jay, was convincing Mickey and Frank that Frank should play the Amphitheatre. Frank eventually consented to an engagement and set the Amphitheatre’s attendance record.

I was there at the beginning; I was there when Dan Slusser was hired; Tom Williams, Mark and Ron Bension, Terry Winnick, Tony Sauber, but I never saw Florida, I never saw the development of the multi-million dollar thrill rides. I never saw Jay’s realization of his dreams, the result of Jay’s magic in engaging the full potential of a cadre of committed ordinary individuals achieving extraordinary results. Sam Gennawey puts you smack in the middle of this amazing journey.

JayBangs is the answer to every company that thinks they need MBAs from Ivy League schools, consultants, and market testing. They need a Jay Stein. There is a complete business/show business education to be found in Sam’s story of Jay Stein and in Jerry Weintraub’s autobiography. Ironically, both of them credit Lew Wasserman.

Robert A. Finkelstein has known Jay Stein for more than 48 years. He was in the first tour guide class along with Mike Ovitz, Tom Mack, and Jay’s second wife, Susan. Finkelstein helped opened Landmark Services and was a key executive in the early years of operating in Yosemite. He is co-chairman of Frank Sinatra Enterprises and the attorney who represents the Frank Sinatra Estate.

Introduction

I am 78 years old, Sid is 80+, Lew is dead, Jules is dead, Drabinsky is in jail, Katzenberg and Spielberg probably don’t want to be interviewed; Eisner will probably say I’m lying when he learns what I could show you. You be the judge. I’m determined to get history right. Would you like to interview me and examine my evidence as to what happened? Let me know.

The plot for the Jay Stein story could have been ripped from the typewriter of a Hollywood screenwriter. All the elements are there. An ambitious guy starts out in the mailroom, works hard, claws his way up the ladder, overcomes obstacles and bloodthirsty enemies, to end up a mogul, and then completely revolutionizes an industry. Then he disappears at the top of his game. Years later, he comes back to set the record straight.

Unlike most Hollywood stories, the Jay Stein story is true. Jay was in charge of the Universal Studios theme parks for almost 30 years. He changed the nature of theme parks, including Disney’s. Walt Disney may have invented the theme park, but Jay is the real “father” of the modern theme park.

Until Jay developed the Universal Studios tours, and ultimately the Universal parks, most second-tier theme parks were crummy affairs with names slapped on off-the-shelf rides. In Disney’s case, there were cute, wholesome attractions, which at best were only mildly scary (in a child-friendly way), along with their versions of something out of real life (or an imagined real life that never actually existed). The Universal parks put visitors in situations that either did not exist in real life or made the experience seem scary or funny, with an adult edge to them; attractions with an attitude.

Jay accomplished it all despite tight budgets and deadlines, often less- than-enthusiastic superiors, and severe external opposition. He insisted on complete involvement (generally from a leadership role) in creation and design, in both the big picture and the smallest details, as well as in advertising and marketing, frequently even coming up with the basic premises of commercials. Jay demanded that his team collaborate, with the best ideas surviving the process. He achieved this through a sometimes cruel, impatient, demanding supervision of subordinates. His management style caused many to leave, but he got the rest to perform beyond their expectations.

Sam Gennawey

Sam Gennawey is a prolific author and Disney historian, a contributor to Planning Los Angeles and other books, as well as a columnist for the popular MiceChat website.

His unique point of view built on his passion for history, his professional training as an urban planner, and his obsession with theme parks has brought speaking invitations from Walt Disney Imagineering, the Walt Disney Family Museum, Disney Creative, the American Planning Association, the California Preservation Foundation, the California League of Cities, and many Disneyana clubs, libraries and podcasts.

He is currently a senior associate at the planning firm of KPA.

If it hadn't been for Bruce Jenner in his helicopter, Jay Stein might have been put in charge of the Disney theme parks.

Jerry Weintraub had managed artists including Frank Sinatra, Neil Diamond, and John Denver. The Universal Amphitheatre was frequently the venue for his clients. Later, he organized and managed large arena concerts. He then became a successful television and movie producer.

When Weintraub called Jay in July 1985, nothing seemed out of the ordinary. Jay had known the producer for many years. The two played tennis weekly, and Jay considered Weintraub a good friend. Also, Jay was always on the hunt for new ideas and new properties to exploit, and he relied on his relationships with producers to give him an edge. Weintraub told Jay that he wanted to meet privately as he had something crucial he wanted to share with him.

Jay prodded for more information, but Weintraub said that he could not discuss it on the phone. Jay told him that he was busy with the pre-production for Florida and could not afford the time to drive all the way out to Weintraub’s house in Malibu. Weintraub then reluctantly divulged that somebody wanted to meet him. Jay agreed, and they set a date to meet.

When Jay arrived at Weintraub’s house on the Pacific coast’s Paradise Cove, he was met by Weintraub’s wife, singer Jane Morgan, and she led him to Weintraub who was sitting outside alone, overlooking the ocean on that beautiful warm day. Morgan offered Jay a drink, and he ordered one of whatever Weintraub was drinking. Jane poured some lemonade and then left.

“Why all the mystery,” Jay asked. Weintraub just smiled and said, “He just called, and he’s running a little late; he will be here shortly.” Ten minutes later, in walks a very tall, thin, patrician-looking man wearing glasses. It was Frank Wells, president of the Walt Disney Company. Jay recognized him immediately. Weintraub made the introductions, and they began about thirty minutes of talking about Wells’ failed attempt to scale Mount Everest in 1983.

Jay was clueless as to why this meeting was taking place. Finally, Wells started talking about Disney and how their Florida parks were performing. He asked Jay numerous questions about how they do things and was effusively complimentary. Then Wells smoothly switched gears and said they were having some “leadership” issues. He told Jay that the man they had running their parks was a long-time loyal employee who was a good soldier, but he lacked imagination and creativity.

Wells was referring to Dick Nunis. Nunis had started at Disneyland just before the opening as one of the trainers and rose to the position of chairman of Walt Disney Attractions. Wells began to trash Nunis, saying that Nunis only knew how to do things one way, and was hesitant to introduce anything new. They were looking to make a change. Wells asked Jay, “How would you like to come work for the Walt Disney Company? You can build the park you want. What would you do differently in our parks?”

During the conversation, a helicopter was circling over Weintraub’s house. Jay noticed Wells beginning to show signs of sweat under his shirt. He was growing very uncomfortable. He finally asked Jerry, “What the hell is going on with that helicopter? Why is it circling your house?” Weintraub began to laugh, “It’s nothing Frank. It’s Bruce Jenner. He does this all the time.”

Now the helicopter was hovering with its pilot looking in their direction. At this point, Wells stood up and said, “I don’t want to continue our discussion at this time. That helicopter is bothering me! I just don’t like it.” Weintraub again tried to convince Wells it was only Jenner “doing his thing.” Wells was not persuaded. The meeting lasted only a couple of minutes longer before the nerve-racked Wells felt like he was being set up. They all quickly shook hands, and he left abruptly.

Once Wells had left, Jay asked Weintraub what the purpose of the meeting was. Weintraub replied, “They were trying to steal you away.” Jay was not so sure about the offer. He never heard from Wells or Disney again. Jay has kept this meeting a secret until now, for this book. Only Tony Sauber and Bob Finkelstein knew of the offer.

There were several occasions over the following years when Jay was publically criticizing Disney and Michael Eisner often responded, “Stein is only mad, angry because we did not hire him.” Every time these remarks came up in print, Jay expected a call from Sheinberg or Wasserman demanding an explanation. They never called, nor did any of Jay’s employees ever question if this were true. Eisner’s credibility within the ranks of MCA was so small and insignificant that everybody just ignored his remarks.

On July 6, 2015, Jerry Weintraub passed away. The day before, he and Jay had breakfast, and they reminisced about the meeting with Wells. Jay speculated on what would have happened if Wells had not been interrupted and had put a firm offer on the table. Jay’s first action would have been to go to Sheinberg and tell him about the offer. He felt that would be the honorable thing to do. If asked to stay, Jay would only ask for two conditions. First, MCA would have to match the Disney offer. More importantly, Sheinberg would have to give Jay an iron-clad commitment that they would build the Florida park with or without a partner. Unfortunately, for Jay, the search for that elusive partner would have to continue.

Continued in "JayBangs"!

When word got back to Disney CEO Michael Eisner that Jay Stein was building a new theme park just down the road, Mickey's white gloves came off and the battle was on.

The man in charge of selling Universal Studios Florida to the world was David Weitzner. Weitzner was trying to extricate himself from the employ of Jerry Weintraub and the Weintraub Entertainment Group. He got a call from Jon Sheinberg, a friend and the son of Sid Sheinberg. Sheinberg told him that there was a top marketing job at Universal and asked if Weitzner was interested. He had worked at the studio twelve years before, and his friend Tom Pollock was running the film division. What could be better?

Instead of meeting with Pollock, Sid Sheinberg had Weitzner meet with Jay. Suddenly, Weitzner realized he was not interviewing for a job heading the marketing department at the film division but the Recreation Division. A day later he met with Jay again; they talked, or as Weitzner describes it, he listened for about an hour. Most of the conversation centered on Universal City. Jay liked that Weitzner came from the film-making side of the business, just like him. Then Jay suggested they take a short drive to MCA’s Planning and Development offices on Lankershim Boulevard to look at some models and artists renderings of the Orlando park.

What Weitzner saw erased the slightest doubt about joining Jay and his team. He thought the elaborate presentation that the team had been using was the most amazing thing and a marketing executive’s dream. He recalled Jay’s smile, which seemed to say, “I told you so.” Weitzner was named the president of Worldwide Marketing the next day.

One thing that made the transition smooth for Weitzner was his close and personal relationship with Steven Spielberg. They had worked together in the past when he was responsible for the marketing campaign for E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial (1982) During one brainstorming meeting with Weitzner, Sheinberg, and Jay, Spielberg suggested the phrase that bests defined the Universal experience: Ride the Movies. At Universal, the theatrical experience would be extended. Not only would visitors see the movie, but they would also become participants. It was a eureka moment.

Weitzner turned to Steve Hayman, Hal Kaufman, and Bruce Miller from the advertising firm Foote, Cone & Belding to develop the marketing plans. Kaufman, a copywriter, described the challenge of going against the strongest brand in the business. He said what Disney did well was selling the forest. If one of the Disney parks burnt down tomorrow, they would be able to advertise “come feel the warmth” and people would visit. Universal’s strength was selling the trees; promoting one attraction at a time. Each attraction was marketed like the release of a major motion picture.

In preparation for a marketing presentation to MCA and Cineplex management before the opening of the Florida park, Jay told the team from Foote, Cone & Belding to lead the effort, and that the meeting participants did not know anything about marketing. He warned them they will be peppered with questions but whatever happened, Jay informed them that he did not want the participants to get a hit off his marketing team. He did not even want one to get out of the infield. One more thing: they were on their own. Jay put the fear of God into his marketing team just before they walked into the conference room. Jay did not want to change the marketing plans, and it was Foote, Cone & Belding’s responsibility to sell it. Jay was proud of the ideas, and he did not want the others to screw it up.

On one side of the table were the top brass from MCA. On the other was the team from Cineplex Odeon. Questions came from the left and the right including Sheinberg asking why there was no advertising for Texas since he just had relatives move into Corpus Christie. In the end, the presentation was successful. Jay turned to Bruce Miller and with typical understated faint praise said, “You did okay.”

After at least a dozen flights from Los Angeles to Orlando, all on Delta Airlines, which had the only two daily non-stop flights, Weitzner noticed that the Disney executives all sat on one side of first-class while the Universal executives sat on the other side. Both teams were trying to cast a wandering eye at what was on the competition’s computer screens. This “us against them” attitude was fostered daily by Jay and to a lesser extent, Sid Sheinberg.

It was on one of these flights that Weitzner came up with a brilliant plan. He noticed that Delta had a monthly in-flight magazine called Sky Magazine. At the time, Delta was known as the “official airline of Walt Disney World.” Weitzner saw the opportunity for a marketing home run and secretly and successfully negotiated an exclusive three-year agreement for thirty-six covers of the magazine. Later, Weitzner said he was sure the salesman who made the deal thought he had died and gone to media heaven until he found out the buyer was none other than Universal Studios.

A few weeks later, at one of the monthly Joint Venture board meetings in Orlando, Weitzner waited for just the right moment, suddenly stood up, and threw down on the table a mocked up copy of the first three-page gatefold with the rendering of the new theme park. Weitzner secretly had the Foote, Cone & Belding team mock up the advertisement. Not even Jay knew what was coming. The response was everything Weitzner hoped for.

When word got back to Michael Eisner, he was less than pleased. Prompted by Jay, the Sky Magazine ads allowed Universal to “tweak the mouse” monthly. After the first year, Wasserman called Weitzner into his office. He told the young executive to cancel the final two years of the contract. Wasserman felt that they had made their point.

Another marketing coup was the billboard campaign. The marketing team secured the best remaining advertisement sites along I-4 and other freeways in the Orlando and central Florida area, especially those roads leading from the airport. One of the things that puzzled Jay was that Disney did not do billboard advertising for their parks. At the very least, once they knew Universal was coming to Orlando; Disney could have acquired the best remaining billboard sites and preempted the marketing campaign.

Universal began to install incredible, one-of-a-kind, three-dimensional billboards with movement. Starting in 1988, central Florida got its first glimpse at the upcoming theme park wars when E.T.’s head and animated 30-foot long fingers cast in three-dimensional Plexiglas beckoned from a Florida interstate. The caption read, “Fly with me in 1990” and at night his eyes would light up. They called these “spectaculars,” and they featured most of the attractions and shows for the yet-to-open Universal Studios Florida. Every few months they would introduce another one. Each billboard cost more than $25,000 each to build. People were so impressed; they would pull over to the side of the road and take photos. Since Universal had locked up the best locations, Disney could not fight back.

Jay had based his strategy on General James H. Doolittle’s 1942 bombing raid on Tokyo just months after the attack on Pearl Harbor. The raid caused negligible material damage to Japan, but it succeeded in its goal of raising American morale and casting doubt in Japan on the ability of its military leaders to defend their home islands. He confessed that he might have overpaid to get some of these billboards, but they got the job done. Every time Michael Eisner drove from the airport to the Disney property, there was no way to avoid them. Disney knew Universal was coming, ready to fight, and fight hard. So successful were the billboards in capturing the public’s attention and the amount of press throughout the country and the world, both Disney and Sea World would soon copy the concept.

Continued in "JayBangs"!

About Theme Park Press

Theme Park Press is the world's leading independent publisher of books about the Disney company, its history, its films and animation, and its theme parks. We make the happiest books on earth!

Our catalog includes guidebooks, memoirs, fiction, popular history, scholarly works, family favorites, and many other titles written by Disney Legends, Disney animators and artists, Mouseketeers, Cast Members, historians, academics, executives, prominent bloggers, and talented first-time authors.

We love chatting about what we do: drop us a line, any time.

Theme Park Press Books

The Unauthorized Story of Walt Disney's Haunted Mansion The Ride Delegate 501 Ways to Make the Most of Your Walt Disney World Vacation The Cotton Candy Road Trip The Wonderful World of Customer Service at Disney Disney Destinies Disney Melodies The Happiest Workplace on Earth Storm over the Bay A Historical Tour of Walt Disney World: Volume 1 Mouse in Transition Mouseketeers Down Under Murder in the Magic Kingdom Walt Disney and the Promise of Progress City Service with Character Son of Faster Cheaper A Tale of Two Resorts I Saw Ariel Do a Keg Stand The Adventures of Young Walt Disney Death in the Tragic Kingdom Two Girls and a Mouse Tale Ears & Bubbles The Easy Guide 2015 Who's the Leader of the Club? Disney's Hollywood Studios Funny Animals Life in the Mouse House The Book of Mouse Disney's Grand Tour The Accidental Mouseketeer The Vault of Walt: Volume 1 The Vault of Walt: Volume 2 The Vault of Walt: Volume 3 Who's Afraid of the Song of the South? Amber Earns Her Ears Ema Earns Her Ears Sara Earns Her Ears Katie Earns Her Ears Brittany Earns Her Ears Walt's People: Volume 1 Walt's People: Volume 2 Walt's People: Volume 13 Walt's People: Volume 14 Walt's People: Volume 15

Write for Theme Park Press

We're always in the market for new authors with great ideas. Or great authors with new ideas. Whichever type of author you are, we'd be happy to discuss your book. Before you contact us, however, please make sure you can answer "yes" to these threshold questions:

Is It Right for Us?

We specialize in books that have some connection to Disney or theme parks. Disney, of course, has become a broad topic, and encompasses not just theme parks and films but comic books, animation, and a big chunk of pop culture. Your book should fit into one (or more) of those broad categories.

Is It Going to Make Money?

There's never a guarantee that any book will make money, but certain types of books are less likely to do so than others. They include: hardcovers, books with color photos, and books that go on forever ("forever" as in 400+ pages). We won't automatically turn down these types of books, but you'll have to be a really good salesman to convince us.

Are You Great to Work With?

Writing books and publishing books should be fun. The last thing you want, and the last thing we want, is a contentious relationship. We work with authors who share our philosophy of no drama and zero attitude, and the desire for a respectful, realistic, mutually beneficial partnership.

If you said "yes" three times, please step inside.