- Visit the Imagineering Graveyard

- Now Sailing: "Skipper Stories" - Tales from the Jungle Cruise

- Coming Soon: The biography of Disney animator Jack Hannah

- Coming Soon: A Haunted Mansion anthology

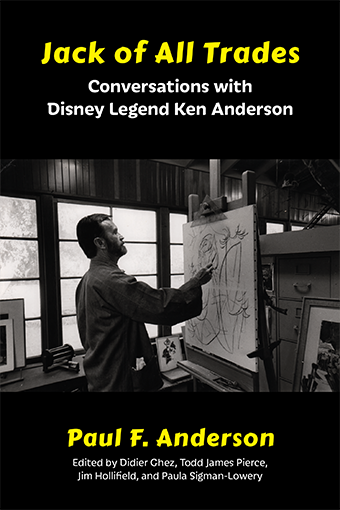

Jack of All Trades

Conversations with Disney Legend Ken Anderson

by Paul F. Anderson | Release Date: March 10, 2017 | Availability: Print, Kindle

Have Ken, Can Do

Before Disney art director, animator, and writer Ken Anderson's death, historian Paul Anderson spent hours talking to Walt Disney's "tenth old man". Their candid, revelatory conversation, presented here for the first time anywhere, charts the creative life of this multi-talented Disney Legend.

Walt Disney famously called his top nine artists and animators the Nine Old Men. Like the fifth Beatle, there was a tenth old man: Ken Anderson. A jack of all trades, Anderson was equally adept in the studio working on films like Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs and One Hundred and One Dalmatians and as an architect and designer of Disneyland and Epcot Center.

Despite an occasionally rocky relationship with Walt, Anderson was trusted with the studio's most important films, and later became an integral part of the Imagineering team responsible for Disneyland.

At times reverential, at times critical, but always revealing, Anderson gives an unvarnished, insider's account of the Disney film and theme park empire like no other.

Over the course of 20 meticulously transcribed and edited cassette tapes, recorded before Anderson's death in 1993, you'll enjoy a unique, extensive, first-hand account of the earliest days of the Disney studio through the decades after Walt's death.

Foreword

Ken Anderson’s flurry of inked lines always fascinated me. This is probably why he has remained my favorite Disney artist throughout the years. That and the fact that he designed the characters of all the Disney features that I grew up with: from The Jungle Book to The Aristocats, Robin Hood, and The Rescuers. Ever since I could afford it I decided to collect his original drawings. I never regretted it: looking at them I feel closer to Disney’s creative process than I do with any other piece of Disney artwork. In other words, I fell in love at a very young age with Ken Anderson’s talent.

Which is why, when I launched the book series Walt’s People, back in 2004, I knew that the first volume needed to contain at least one interview with Ken. And I knew who to talk to, of course: my good friend and fellow Disney historian, Paul F. Anderson.

In the late 1980s, Paul had struck a friendship with Ken, who came to consider him as his adopted son. Helped by this friendship and motivated by his deep interest in Disney history, Paul decided to conduct a long oral history with Walt’s “jack-of-all-trades.” Twenty-one tapes later, in 1993, the oral history was abruptly interrupted when Ken passed away.

I had always dreamed of reading these interviews and of seeing them released in one single place, in book form.

Thanks to the efforts of transcribers Kevin Carpenter, Carol Cotter, Ryan Ehrfurt, Skye Lobell, James Marks, David Skipper, and Julie Svendsen, as well as to the work of my co-editors James Hollifield, Todd James Pierce, and Paula Sigman-Lowery, I am glad to finally see this long-time goal become reality, through the generosity of Bob McLain and Theme Park Press.

While reading these interviews, it is important to always keep in mind that no statement from any interview should ever be considered as the absolute truth, as Ken Anderson might have misremembered the facts, may have seen only part of the events described, or may have his own personal reasons for representing reality in a certain way. And since those interviews were conducted at the end of his life over the course of a few years, you will notice some understandable discrepancies in Ken’s recollections. Despite those discrepancies Ken’s memories remain fascinating.

You will notice that tape 9 is missing. Despite our best efforts we were unable to locate it. If and when we do so, its content will be released in a future volume of Walt’s People. In the meantime, we hope you will enjoy the fascinating life and time of Walt’s “jack of all trades,” Disney Legend Ken Anderson.

Paul F. Anderson

Paul F. Anderson has spent well over half of his life researching, writing, and delving into the creative legacy of Walt Disney. As of this writing, he has done over 250 interviews. Feeling a need and a responsibility for his work to be shared with others, Paul started a historical journal devoted to the creative legacy of Walt Disney titled Persistence of Vision, for which he served as editor and publisher.

In addition to conducting interviews, researching Disney history, and writing in-depth examinations of Disney topics, Paul travels across the United States to give lectures and talks on Disney. In 2000 he was invited to be an adjunct professor at Brigham Young University to teach a class on Walt Disney and American culture through the American Studies program. He has authored several books, including The Davy Crockett Craze, which takes a scholarly look at the 1950s Disney cultural phenomenon.

As the recognized authority on Walt Disney’s later projects, he worked for the Walt Disney Family Educational Foundation and wrote two essays for their CD-ROM on Walt Disney’s life. He also served as a historical consultant for the Disney family on the documentary film Walt Disney: The Man Behind the Myth and was also interviewed for the film.

Strip away all the heavy mythology surrounding the early Disney Studio and you're left with just a bunch of guys swapping stories and pulling pranks.

Ken Anderson: I wanted to get in on story, stories that could be adapted. A well-known story had a chance of being accepted. We thought we had no chance of being accepted if we came up with an original story; we had to sell that original story to people, we’d have to get an in first.

Paul F. Anderson: In the late 1940s, was it still pretty much one picture at a time and then soon as that was over you’d work on the next one? Was there ever any crossover where you may have been working on two or three pictures at a time that you remember?

KA: I always had something that I was doing.

[On trying new approaches to styling:]

KA: [We’d try] taking an approach in an attempt to find out what styles we could use that would be available to us to utilize.… And if nothing else it did prove that that didn’t work, but that we’d made a new style: something that was partly Mary Blair’s, and something that was brand new.

PA: Did you have a style that you had worked with and created for Melody Time, for Pecos Bill or Johnny Appleseed, Little Toot? Blame It on the Samba?

KA: No, we didn’t. Each one was a style that suggested itself.

PA: Were there any styles that you suggested? Or something you leaned toward or wanted to try?

KA: Well, we were trying to make Mary Blair’s style work. And it just wouldn’t. But we didn’t know it actually wouldn’t, we just knew it was damn hard to do: to make a two-dimensional scene be a three-dimensional scene—it’s still to be a two-dimensional scene.

PA: Is there anything you can think of that maybe came close, where you guys made her style work? It just couldn’t be done?

KA: It just never went anywhere.

PA: What were you like at the studio in the 1940s? Were you shy, were you outgoing, did you get to work early?

KA: I’ve always been outgoing!

PA: Well, you’re a great storyteller. Were you storytelling then, too?

KA: I think I’ve always been the same.

PA: Hopping from room to room?

KA: Not too much; I think I was too involved in the appearance of things and the drawing of things. At the desk, I was too involved with my desk to get up and go somewhere and tell stories.

PA: Do you remember what your desk was like? Did you have doodads or knickknacks from home? What kind of things did you have on your desk?

KA: Mostly mementoes of what we were working on.

PA: Do you remember who you were sharing a room with at this time? Was it Hugh Hennesy still?

KA: I was all alone.

PA: Who were some of the people you liked to hang around with in the 1940s at the studio?

KA: I remember Hugh, Charlie Philippi, Tom Codrick, and all the top animators including.…

PA: Frank and Ollie?

KA: Yeah. And the storymen.

PA: Were you involved in the 1940s with any of the studio activities, such as the sports, or baseball or softball teams?

KA: Not in a professional way. Not in a way that we were vying for a title. I was naturally always involved in the animation or in the actual work, or the trial.

PA: You were quite a bunch of pranksters in the 1940s. Didn’t Walt have a saying once, “Why don’t you write some of these pranks into the movies?”

KA: Yeah. Some of the stuff [ended up] on the screen.

PA: [Do you] remember any of the pranks that were played on you, or that you played on anybody else? Would you just kind of run into somebody’s room and steal their pencil? Or were these elaborate pranks? Or both?

KA: They were elaborate pranks, but they were never planned, we never knew ahead of time what they were going to be, or when they were going to take place. But we’d always play a prank on somebody new, if he needed a prank. If there was some reason for a prank to take place, then it always would.

One of the new men was a know-it-all and kept telling everybody he knew it all. He was bragging about his frog’s food, this animal food. It was the best damn stuff: it would make anything grow, and it was wonderful. And we got sick and tired of listening to him tell about it. So we went in and we took a frog that was bigger than the one he had, and substituted it for him, and the next day he was really pleased that this food he was using had made it work so well. And we kept this up with bigger and bigger frogs, and he was just absolutely ecstatic. And then we decided to make them smaller, and we went down, down, down, down using the smaller frogs—and he was quite distressed that this frog food had backfired on him. It was going in the wrong direction.

PA: Were you always outgoing?

KA: I was always trying. I wasn’t holding back for anybody. If there’s anybody that took precedence in a meeting over me, it was Walt.

PA: That was quite a change from when you started in the 1930s in the meetings and you were kind of … surrounded by all these guys, and didn’t want to say much. Was this a confidence that was built up within you over the years, and the product that turned out?

KA: Yes, if anything, that’s what enabled me to do that. But I don’t think I had enough presence of mind to take over meetings and to take over the studio work. I wasn’t going to run everything. I just think that I had more self-confidence than I had had before, and it enabled me to make suggestions and do things that I hadn’t been able to do before. And also to admire other work that was very good.

PA: That’s quite an accomplishment considering you were in a profession with a man like Walt who wasn’t very complimentary. The only way you found out if he liked your stuff was from somebody else.

KA: That’s true. And that didn’t always work either. Sometimes he never told anybody. If you were still working, you were doing well.

PA: That’s how you knew?

KA: That’s the only way you knew.

PA: As long as you were still getting a paycheck. Did that ever bother you?

KA: It constantly worried me. I didn’t know until it was all over with that I still had a job.

PA: And yet in the 1940s, considering you could’ve made more money doing architecture … there was something that was keeping you there. You must’ve loved the place.

KA: I’m sure I did. I loved the challenge. Every day it was presented to you as a different challenge. It never was the same thing, and so it was always fresh. A fresh challenge, there was more to conquer.

PA: When you think about it, I mean, what could be more challenging than Walt?

KA: [Laughs] I can’t think of anything.

Continued in "Jack of All Trades"!

The Disney company denies that Walt Disney recorded a "secret" film for a select few to watch upon his death. In the film, Walt allegedly revealed his plans for taking the company forward into new films and, of course, EPCOT. But Disney says it never happened. Ken Anderson watched that film....

Paul F. Anderson: There was always a rumor that after Walt’s death, a couple weeks or months, perhaps, that there was a film of Walt talking to everybody. A bunch of the higher-up people went into a boardroom, turned off the light, and turned on a film and it was Walt. He was talking to each person individually and outlining ideas that he wanted to go on. Have you ever heard that rumor?

Ken Anderson: Yes.

PA: Do you know anything about it?

KA: I was in the meeting, but I don’t know anything about it. I don’t remember being particularly addressed by him.

PA: But you remember seeing a film where he talked about what he wanted? The Walt Disney Company denies that the film exists.

KA: It does.

PA: How many people were in the boardroom? I heard it was just twelve or fifteen or so.

KA: I think that’s right. It wasn’t a big meeting. He didn’t talk to everybody; he talked to us all as a group. He was portraying what he wanted to happen in Disney World mostly, but Walt didn’t have a feeling that the studio would continue without him, or that anything would happen without him. It was his hobby, and anything that would happen there, he could only visualize it if he was at the center of it.

PA: So then after that, it left quite a void.

KA: I thought it was all over. As far as I was concerned, it was.

PA: But Walt must have wanted his plans to go on if he left this film.

KA: I think the film that existed was just a picture of him and not his drawings or ideas. Well, there were a few drawings and ideas, but it wasn’t a wonderful film.

PA: It was just him talking, saying what he wanted.

KA: Yeah, that’s all it was. Yeah, which was a very magnificent one for EPCOT, which was what he was concentrating on, because Disney World was just to be another Disneyland, placed on the East Coast. But his big thought was this wonderful land that he was preparing next to Disney World, an Environmental Prototype Community of the Future, and he waxed eloquent on that. He was really sold on it. He had in mind these eight different lands within the land that would be applied for, and each land would be a different area. So if there was an agricultural area like the Midwest of the United States, it would be a complete Midwestern community of agriculture, and there would be every beneficial thing that had been invented or discovered. Our agriculture would be taken care of. And this would consist of schools and everything else. That would be the primary interest in this area. And then all eight would be different ones. There’d be a mill area, which would take into account everything from coal to steel, and it would be beneficial and that way it would teach … it would be a wonderful area. There would be a wonderful way of making that a better area than it could possibly be without his advancement. And why each one of these would be so good would be that they would be made up of all of the brains of America for each free land. The one on mills would have to do with all those who had thought of mills and what they had to do and it would be composed of the best brains for each area. So they would have maybe teams of five or six outstanding … they were all the top people [who] would be involved with the development of each area that they were primarily interested in. There may be, just as a guess, maybe forty or fifty experts constantly involved, making sure that each area worked for the best for that particular area.

The whole thing was such a wonderful idea, but everybody said, “Who the hell is Walt Disney? A god? How can he tell these people the best way to live?” When Walt died, it was with that in mind that all these people were disgusted, because Walt was playing a god. So, they had to discard his idea, but they went to work on this idea which was Roy’s, I think, of all the different lands in the world, each land would be depicting the best things for each country, and it would be an entertainment area which would show the best parts of the land as it is, and the best parts of the land to be developed in the future. That’s known as EPCOT.

PA: The original idea that you said would be different lands that Walt had planned, was that something that you heard Walt tell you or was that something that you read?

KA: No, that’s something that Walt told me. In fact, when he was in the hospital, he was lying back and he had his brother, Roy, come over and he was pointing out the tiles on the ceiling as different areas, depicting the different scales so he could have each area be a hundred square feet or it could be a half mile. He could have it be whatever he wanted. He had visualized all these areas and what went on in each one, and he lay there pointing these things out to Roy as an advisable thing for EPCOT. And that was with the idea in mind that there were eight communities which would be completely redone every ten years with the advent of a whole new succession of brilliant brains that came in. They would be able to amass all their information and see what they had there that worked, didn’t work, and then they would redo it. So every ten years it would be rebuilt as a better and newer version. But his whole idea was crap, because it was too dictatorial from the standpoint of the people who he’d accept. It’s a wonder, really, that they went ahead with anything. The idea dried up right after the meeting of this great idea of Walt’s. It was canned for a while as if there wasn’t gonna be any EPCOT, and then in the depths of somewhere this idea came up. Someone said, “Give it to Roy,” but I don’t know who, and EPCOT became all these different lands, of which Africa should be one.

PA: Everyone always talks about what Walt wanted for EPCOT, but nobody explains some of the ideas he had. As excited as he was, he must have had some ideas. He must have talked to people about it.

KA: Oh, he sure did.

Continued in "Jack of All Trades"!

About Theme Park Press

Theme Park Press is the world's leading independent publisher of books about the Disney company, its history, its films and animation, and its theme parks. We make the happiest books on earth!

Our catalog includes guidebooks, memoirs, fiction, popular history, scholarly works, family favorites, and many other titles written by Disney Legends, Disney animators and artists, Mouseketeers, Cast Members, historians, academics, executives, prominent bloggers, and talented first-time authors.

We love chatting about what we do: drop us a line, any time.

Theme Park Press Books

The Unauthorized Story of Walt Disney's Haunted Mansion The Ride Delegate 501 Ways to Make the Most of Your Walt Disney World Vacation The Cotton Candy Road Trip The Wonderful World of Customer Service at Disney Disney Destinies Disney Melodies The Happiest Workplace on Earth Storm over the Bay A Historical Tour of Walt Disney World: Volume 1 Mouse in Transition Mouseketeers Down Under Murder in the Magic Kingdom Walt Disney and the Promise of Progress City Service with Character Son of Faster Cheaper A Tale of Two Resorts I Saw Ariel Do a Keg Stand The Adventures of Young Walt Disney Death in the Tragic Kingdom Two Girls and a Mouse Tale Ears & Bubbles The Easy Guide 2015 Who's the Leader of the Club? Disney's Hollywood Studios Funny Animals Life in the Mouse House The Book of Mouse Disney's Grand Tour The Accidental Mouseketeer The Vault of Walt: Volume 1 The Vault of Walt: Volume 2 The Vault of Walt: Volume 3 Who's Afraid of the Song of the South? Amber Earns Her Ears Ema Earns Her Ears Sara Earns Her Ears Katie Earns Her Ears Brittany Earns Her Ears Walt's People: Volume 1 Walt's People: Volume 2 Walt's People: Volume 13 Walt's People: Volume 14 Walt's People: Volume 15

Write for Theme Park Press

We're always in the market for new authors with great ideas. Or great authors with new ideas. Whichever type of author you are, we'd be happy to discuss your book. Before you contact us, however, please make sure you can answer "yes" to these threshold questions:

Is It Right for Us?

We specialize in books that have some connection to Disney or theme parks. Disney, of course, has become a broad topic, and encompasses not just theme parks and films but comic books, animation, and a big chunk of pop culture. Your book should fit into one (or more) of those broad categories.

Is It Going to Make Money?

There's never a guarantee that any book will make money, but certain types of books are less likely to do so than others. They include: hardcovers, books with color photos, and books that go on forever ("forever" as in 400+ pages). We won't automatically turn down these types of books, but you'll have to be a really good salesman to convince us.

Are You Great to Work With?

Writing books and publishing books should be fun. The last thing you want, and the last thing we want, is a contentious relationship. We work with authors who share our philosophy of no drama and zero attitude, and the desire for a respectful, realistic, mutually beneficial partnership.

If you said "yes" three times, please step inside.