- Visit the Imagineering Graveyard

- Now Sailing: "Skipper Stories" - Tales from the Jungle Cruise

- Coming Soon: The biography of Disney animator Jack Hannah

- Coming Soon: A Haunted Mansion anthology

The Imagineering Pyramid

Using Disney Theme Park Design Principles to Develop and Promote Your Creative Ideas

by Louis J. Prosperi | Release Date: April 16, 2016 | Availability: Print, Kindle

Learn from the Disney Imagineers

Creativity. Innovation. Success. That's Disney Imagineering. It was the Imagineers who brought Walt Disney's dreams to life. Now you can tap into the principles of Imagineering to make your personal and professional dreams come true.

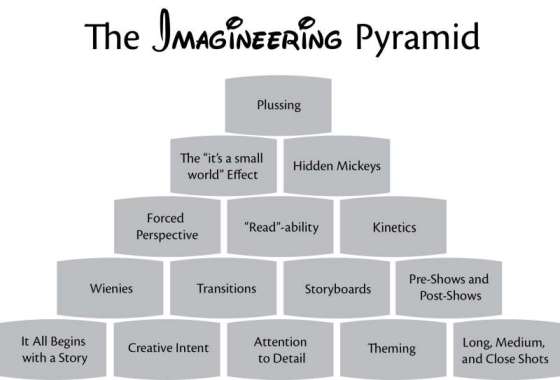

Even if you're not building a theme park, the Imagineering Pyramid can help you plan and achieve any creative goal. Lou Prosperi designed the pyramid from the essential building blocks of Disney Imagineering. He teaches you how to apply the pyramid to your next project, how to execute each step efficiently and creatively, and most important, how to succeed.

The Imagineering Pyramid is a revolutionary creative framework that anyone can use in their daily lives, whether at home or on the job. Prosperi shares with you:

- How to use "The Art of the Show" to stay focused on your mission.

- Practical tutorials for each of the fifteen building blocks that make up the pyramid.

- Creative Intent, Theming, "Read"-ability, Kinetics, Plussing, and other Imagineering concepts.

- Imagineering beyond the berm: how to apply the pyramid to fields as diverse as game design and executive leadership.

- An "Imagineering Library" of books to further your studies.

UNLEASH YOUR CREATIVITY WITH THE DISNEY IMAGINEERS!

Table of Contents

Foreword

Preface

Introduction

Part One: PreShow—Peeking Over the Berm

Chapter 1: What is Imagineering?

Chapter 2: A Quick Look at the Pyramid

Chapter 3: Imagineering and the Power of Vision

Part Two: The Imagineering Pyramid

Chapter 4: The Art of the Show

Chapter 5: It All Begins with a Story

Chapter 6: Creative Intent

Chapter 7: Attention to Detail

Chapter 8: Theming

Chapter 9: Long, Medium, and Close Shots

Chapter 10: Wienies

Chapter 11: Transitions

Chapter 12: Storyboards

Chapter 13: Pre-Shows and Post-Shows

Chapter 14: Forced Perspective

Chapter 15: “Read”-ability

Chapter 16: Kinetics

Chapter 17: The “it’s a small world” Effect

Chapter 18: Hidden Mickeys

Chapter 19: Plussing

Part Three: Imagineering Beyond the Berm

Chapter 20: Imagineering Game Design

Chapter 21: Imagineering Instructional Design

Chapter 22: Imagineering Management and Leadership

Chapter 23: Post-Show—Final Thoughts and a Challenge

Appendix A: My Imagineering Library

Appendix B: The Imagineering Pyramid Checklist

Bibliography

Acknowledgments

About the Imagineering Toolbox Series

Foreword

How do they do that?

If you are like me, you have asked yourself that question a thousand times while experiencing the magic of Disney. Regardless of whether it is a moment of animation, a memory from an attraction, or the unmistakable ambiance of a theme park, our curiosity (one of Walt’s most consistent character traits) inevitably gets the best of us. It is then that we just need to know, “How do they do that?”

Making magic isn’t easy. But in the pages ahead, you have the opportunity to discover the method behind the magic. The Imagineering Pyramid provides the average layperson, people just like you and me, the opportunity to learn and apply the very principles the Imagineers use in creating and designing the most immersive attractions and theme parks in the world.

At some level, we all wish to bring home more than memories after visiting a Disney park. This is why Disneyland opened with souvenir shops on day one and we have been collecting Disneyana memorabilia ever since. The belief that your take-away can be more significant than a t-shirt, or even your own personalized pair of Mickey Ears, was my motivation for writing The Wisdom of Walt: Leadership Lessons from The Happiest Place on Earth. Disneyland is not just the place where dreams come true. Disneyland can be the place that inspires and shows us how to make our dreams come true.

Much to my delight, Lou Prosperi has taken this concept even further. Creativity is not an easy language to translate, but in the magical pages that follow you will see that Lou successfully shows us how to translate the work of the Imagineers into almost any creative endeavor. As a bonus, this course on creativity also allows us to discover some of the history behind the parks and hear stories about some of our most beloved attractions.

One of my favorite stories about the dream of Disneyland involves Walt’s original work with architects who never could understand what it was that Walt wanted. Exasperated, the architects themselves eventually encouraged Walt to turn inward and find people on his own team who could build the stage and tell the stories that would one day become Disneyland. The architects who turned Walt down had in fact provided him with sage advice. Living in Southern California, I have the privilege of talking with folks who visited the park that first year, or maybe were even there on opening day. To a person they will say, “I had never seen anything like it. There was nothing like it anywhere in the world.”

Walt’s successful staff of studio craftsman would eventually evolve into the famed Imagineers who would go on to build not just Disneyland, but Disney parks and Disney attractions around the world, including the new Disneyland Shanghai, scheduled to open in 2016. Today, the Happiest Place on Earth is one of the most replicated places on earth. And to think it all started with a mouse—a mouse, a man, and a creative core of Imagineers who would push the limits of themed entertainment to heights never before believed possible or even imagined.

You can become your own replicator and be an “armchair Imagineer” by reading The Imagineering Pyramid. But don’t just read this book; be sure to actually apply the pyramid’s principles. Who knows, successful implementation could well result in someone experiencing your creative project and asking “How did you do that?”

Preface

“I bet that’s him,” my wife said as the young man walked past us.

“You think so? I guess we’ll find out.”

It was 11:20 on a Friday morning in late August, and we (my wife and kids and I) were waiting in the lobby of the Hollywood Brown Derby restaurant at Disney’s Hollywood Studios theme park at Walt Disney World. We were there for the “Dining with an Imagineer” dining experience where you have lunch with one of the people who design and build Disney theme park attractions and shows.

As we waited in the lobby for our dining experience to begin, a young man (well, younger than me, anyway) wearing khaki shorts and a black polo jersey had just walked past us into the restaurant. Since the restaurant hadn’t opened yet and the man hadn’t checked in with the host, we figured he had to be a cast member (the Disney term for employee). We would soon discover that my wife was right, and that he was, in fact, “our” Imagineer.

For me, this lunch was the part of our trip that I was most looking forward to. The chance to talk with an Imagineer about Disney theme parks was something I just couldn’t pass up. I had even tried to find out in advance the name of our Imagineer, in case it was someone I recognized, but the cast members at the restaurant either didn’t know (which I think was the case) or didn’t want to spoil the surprise.

Just after 11:30, the hostess led us, along with four other people, through the main dining room and into the Bamboo Room, a private area in the back of the restaurant where the young man in the khaki shorts and black jersey was waiting for us. The young man introduced himself as Jason Grandt, a senior concept designer, and we spent the next two-and-a-half hours enjoying a wonderful lunch and hearing stories about how the Imagineers work. He told us all sorts of stories, ranging from old ones about Walt Disney and some of the earliest Imagineers, to more recent accounts of his own experiences. I felt like a kid on Christmas day.

So, why was this such a big deal to me? Well, to understand that, we need to go back in time…

My interest (some friends and family might say obsession) with Walt Disney World in general and Imagineering in specific began, not surprisingly, with my first visit to the park. It was in May 1993 when my wife and I went to Disney World on our honeymoon. Prior to this, my only exposure to the Disney theme parks was through pictures and TV, and while a picture may be worth a thousand words, that’s still not enough to convey the true wonder, magic, and delight that I felt when I first experienced the “Most Magical Place on Earth” (not the “Happiest Place on Earth”, which is the official tagline for Disneyland).

We started our visit at Epcot (or as it was known then, EPCOT Center). The park wasn’t crowded at all, and we were able to walk onto nearly every attraction. We started with Spaceship Earth and made our way clockwise around Future World, starting in Future World East at the Universe of Energy, Wonders of Life, Horizons, and the World of Motion, followed by Future World West and Journey into Imagination, The Land, and The Living Seas.

While each of these attractions was more amazing than the last, exposing me to a type of entertainment I had never experienced or even imagined before, it was Journey into Imagination that really captured my imagination (pardon the pun) and began my journey along the path that would lead to that lunch with our Imagineer and writing this book. Following Dreamfinder and Figment along their “flight of fancy” that first time reminded me of the power of imagination and where it can take us. I had always been a kid at heart (or as a former girlfriend used to say, “childlike, not childish”), and that ride really spoke to the kid inside me.

You’ll have to forgive the melodrama, but I believe that riding Journey into Imagination in May 1993 was a pivotal moment in my life.

And if Journey into Imagination had started my journey, my first visit to the Magic Kingdom the next day sealed the deal forever. There was no turning back. I remember being nearly awestruck seeing Cinderella Castle for the first time. It seemed like it couldn’t be real, but there it was. I remember taking pictures of the castle from different angles, hoping to capture that feeling forever on film, but unfortunately, photography is not my strong suit. In the end it didn’t matter. The magic born from Imagineering had implanted itself into my heart, mind, and soul, and I would never forget.

But just to help me keep the magic alive, I bought what books I could find about the parks, starting with a souvenir guide and a big full-color hardcover book entitled Walt Disney World: Twenty Years of Magic.

I found myself back at Disney World two years later, in 1995, along with my whole family, to celebrate my parents’ 40th anniversary. I made sure to visit my friends Figment and Dreamfinder at Journey into Imagination a couple of times, and soaked in even more of the Imagineering magic. And of course, I bought more books. This time I found books about Walt Disney himself, including a book of his quotes and a biography (The Man Behind the Magic: The Story of Walt Disney), as well as a book about the Disney company (The Disney Touch, by Ron Grover). I had looked for more books about the parks and Imagineering, but back in those days, there simply weren’t that many books about the subject to be had, or if there were, I couldn’t find them. Years later I would learn about other Imagineering resources, such as The “E” Ticket magazine, but at that time, I was limited to what I could find at Disney World gift shops and in the local bookstore (and to what fit within my budget).

That changed in 1996 with the publication of Walt Disney Imagineering: A Behind-the-Dreams Look at Making the Magic Real. This was the first true glimpse I got into the process of how the Imagineers design and build Disney theme park attractions. It would turn out to be just the first of many items in my Imagineering library, but it would be awhile before I was able to add more.

Fast forward to 2005. Between 1996 and 2005, real life and other interests had (temporarily) drawn my attention away from Disney parks and Imagineering. During this time my wife and I had our first child (my son, Nathan), I returned to college to get my degree, we moved from Chicago back to Massachusetts, and then we had our second child (my daughter, Samantha).

My interest and passion in Disney parks was rekindled when we visited Walt Disney World again, this time with my wife’s family to celebrate her parents’ 40th anniversary. This was also the first time my kids had visited Disney World, and to see it through their eyes helped remind me of just how magical and special a place it can be. During this trip I also learned there were lots of other books that would eventually join my Imagineering library. The book I bought while there was The Imagineering Way: Ideas to Ignite Your Creativity, a collection of essays and stories written by Disney Imagineers (including Jason Grandt, the Imagineer we would meet a few years later) about creativity and the creative process. It was another look into the Imagineering process, and it re-ignited my interest in Imagineering. From that point on, I began tracking down every book or resource I could about Imagineering, Disney theme parks, and Disney in general.

Since that time, I’ve been to Disney World several more times, and have added dozens of books to my Imagineering library. Some of the highlights of my library include John Hench’s Designing Disney: Imagineering and the Art of the Show; Karal Marling’s Designing Disney’s Theme Parks: The Architecture of Reassurance; Jeff Kurtti’s Walt Disney’s Imagineering Legends and the Genesis of the Disney Theme Park; Jason Surrell’s books about the Haunted Mansion, Pirates of the Caribbean, and the Disney Mountains; the Imagineering Field Guides by Alex Wright; and many, many others.

As I added each new book to my Imagineering library, I didn’t just read each and set it aside. I studied each one, often cross-checking stories and references across other books in my library to make sure I understood how it all fit together. I’ve read some of the books in my library four or five times (in particular, Alex Wright’s Imagineering Field Guide series, which I’ve also indexed). Each time I re-read a book I come away with some new distinction or discovery. I even transcribed the entire Imagineering glossary from Walt Disney Imagineering: A Behind the Dreams Look at Making More Magic Real, word for word. (I told you my family might say I’m obsessed.)

As if I wasn’t already obsessed enough, my interest in Imagineering got an additional boost when I had an “a-ha” moment that would further deepen my interest in Imagineering and eventually lead to our lunch with an Imagineer and to this book. How is that? Well, one day I was reading Pirates of the Caribbean: From the Magic Kingdom to the Movies by Jason Surrell (not for the first time) and I came across the following:

In a ride system, you only have a few seconds to say something about a figure through your art, Blaine [Gibson] told Randy Bright. So we exaggerate their features, especially the facial features, so they can be quickly and easily understood from a distance.

I was working as a technical writer and trainer at the time, and as I read those words, I thought to myself “that’s like what we do when we develop training materials—we simplify concepts and ideas so that students can understand them quickly and easily” (something I now call “read”-ability).

As I began to look at Imagineering through the lens of instructional design, I realized that many of the techniques and principles used by Walt Disney Imagineering could also have applications not just for instructional design, but across a wide variety of activities that lie outside the parks, or “beyond the berm”.

If I had been eager to find new books about Imagineering before, this grew my appetite even more. I scoured every book in my library (and continued to add new ones), looking for the principles behind the practices, the hows and whys that explain how Imagineering magic really works. And as you might guess, I found further examples of how the Imagineering processes and practices could be applied to instructional design and other creative fields.

It was this continued search that was a main driver for my wanting to have that lunch with an Imagineer (you didn’t think I’d get back to that, did you?). I wanted to be able to pick the Imagineer’s brain about their processes, techniques, and “theory”. I tried my best to scale back my enthusiasm and not completely dominate the conversation, but I’m not sure how well I succeeded. The lunch exceeded my expectations. Our Imagineer was a gracious host, the food was excellent (especially the Double Vanilla Bean Crème Brûlée), and his answers to my questions helped me clarify some of the distinctions I had been making about how Imagineering works.

My ongoing journey into Imagineering is also what brought about this book. The concepts of the Imagineering Pyramid outlined herein first took form as a presentation about instructional design called “The Imagineering Model: Instructional Design in the Happiest Place on Earth” that I gave to some curriculum developer colleagues. I later expanded and refined the material and presented “The Imagineering Model: What Disney Theme Parks Can Teach Us About Instructional Design” at a Society for Applied Learning Technology (SALT) conference in Orlando in 2011 (during which I also visited Disney World. Big surprise, I know!) Then, in early 2014, I presented a third version (renamed as “The Imagineering Model: Applying Disney Theme Park Design Principles to Instructional Design”) as a SALT webinar. I posted both versions of the presentation on Scribd and SlideShare, and caught the attention of Theme Park Press, who reached out to me about expanding the presentation into a book.

I’m still buying Imagineering books, both old and new, and am still on my journey into Imagineering. This book is a next step in that journey, and I’m glad to have you along for this part of it.

Introduction

I’ve been fortunate to have been involved in a number of creative fields for much of my adult life. When I first went to college, I studied music composition, and in addition to my original music, I also wrote several arrangements for a small jazz ensemble. Later I worked for as a freelance game designer before getting a full-time position as a product line developer for a small game company. After leaving that job, I did more freelance game design work, then worked for nine years years as a technical writer and trainer. For the past six years, I’ve served as the manager of a team of technical writers and curriculum developers for a small business unit in a large enterprise software company.

Now, I know what some of you may be thinking: “Music and game design are creative fields, but technical writing and training? Those don’t seem all that creative.” I disagree. I believe that there is a creative aspect to nearly everything we do. Even the most seemingly mundane of activities involves some level of creativity.

I’m not alone in this belief in the diverse nature of creativity. In The Creative Habit: Learn It and Use It for Life, renowned choreographer Twyla Tharp writes: “Creativity is not just for artists. It’s for business people looking for a new way to close a sale; it’s for engineers trying to solve a problem; it’s for parents who want their children to see the world in more than one way.” In their book Creative Confidence: Unleashing the Creative Potential Within Us All, authors Tom Kelley and David Kelly refer to the idea that creativity is something that applies only to some people as ‘the creativity myth’. It is a myth that far too many people share.” They also tell us: “Creativity is much broader and more universal than what people typically consider the ‘artistic’ fields. We think of creativity as using your imagination to create something new in the world. Creativity comes into play wherever you have the opportunity to generate new ideas, solutions, or approaches.”

Likewise, I believe everyone is creative, even the people who tell you that they “don’t have a creative bone in their body”. The challenge for many of us lies in finding the right model of how creativity and the creative process works so we can apply it in our own fields. This book is my attempt at providing just such a model. But before we get to that, let’s look at that word “creativity” a bit.

Creativity is a “magnetic” word for me. It draws my attention like a magnet.

You know when you buy a new car, suddenly you see that car everywhere? You may have never noticed it before, but now, everywhere you look there’s a car just like yours. Did all those people also just buy the same type of car? Most likely not. What’s happened is that your brain and perceptions have become more sensitive to that type of car because it’s important to you. This recently happened to my wife and I when we bought a new car. One or two days after buying that car, I started noticing it on the roads far more often than I ever had before.

A similar thing happens when we set goals. After we’ve set a goal and gotten specific about what we can do to accomplish that goal, we start noticing more things that can contribute to us accomplishing that goal. Our brain filters out input that doesn’t help us make progress on our goals, freeing us up to notice all those things that can help.

I have a similar experience with certain words, and I suspect the same is true for many of us. I think most of us have our own magnetic words, related to whatever it is that interests us, and those words capture our attention more than others. Some of my magnetic words include “Disney”, “Imagineering”, “imagination”, “creativity”, and “innovation”. When I stumble upon an online article, blog, or Facebook post about any one of these, it immediately captures my attention and I spend a few moments investigating. Most times I quickly scan the item to see if it’s something I want to devote more time to, and if so, I either make a note of it or spend a few minutes reading further. I also intentionally seek out online content about some of these words as well. I have Google Alerts set up for “Disney”, “Imagineering”, and “creativity”, among others, and get daily updates with links to various online sources related to each.

I said earlier that I suspect many of us have own set of magnetic words. Some of those may be unique, but many of us also share magnetic words with those who share common interests. For instance, I strongly suspect that I’m not alone in having “Disney” or “Imagineering” among my magnetic words. I would guess that many of you are reading this book because of your own interest in Disney and Imagineering. And while some words are magnetic to only a (relatively) small number of people, some are shared by so many that they become nearly universal. Creativity is one of the latter. Over the last several years, creativity has gained more and more attention, and has become a buzz word in business. In a blog post called “Creativity Creep” from September 2, 2014, on The New Yorker website, Joshua Rothman writes:

Every culture elects some central virtues, and creativity is one of ours. In fact, right now, we’re living through a creativity boom. Few qualities are more sought after, few skills more envied. Everyone wants to be more creative—how else, we think, can we become fully realized people?

Creativity is now a literary genre unto itself: every year, more and more creativity books promise to teach creativity to the uncreative. A tower of them has risen on my desk—Ed Catmull and Amy Wallace’s Creativity, Inc.; Philip Petit’s Creativity: The Perfect Crime—each aiming to “unleash”, “unblock”, or “start the flow” of creativity at home, in the arts, or at work. Work-based creativity, especially, is a growth area. In Creativity on Demand, one of the business-minded books, the creativity guru Michael Gelb reports on a 2010 survey conducted by IBM’s Institute for Business Values, which asked fifteen hundred chief executives what they valued in their employees. “Although ‘execution’ and ‘engagement’ continue to be highly valued,” Gelb reports, “the CEOs had a new number-one priority: creativity,” which is now seen as “the key to successful leadership in an increasingly complex world.”

And so, if creativity is in such high demand, where can we turn to help us cultivate and develop our own creativity? Many of us turn to books. As Rothman notes, creativity has almost become its own literary genre, with dozens of books being published every year covering different aspects of creativity. Beyond books, the internet offers a seemingly endless array of online articles and blog posts focused on creativity as well, and nearly every day there are new items posted.

But even with all of the books and online content, I still think there’s something missing from the “creativity literature”. My observation is that the creativity literature seems focused on two main areas: 1) theory about creativity (traits of creative people, etc.) and 2) tips and techniques to help us “be more creative” or “generate new ideas”.

While these are both valuable and useful to people wanting to be more creative, from my point of view what’s missing is a model for the creative process—an example that we can look to for concepts and principles that can be applied across a variety of creative fields (and remember, there is a creative aspect to nearly everything we do).

Now. you might be asking, “Isn’t being more creative a good thing?” Well, I suppose, but what exactly does “being more creative” even mean? Isn’t it important to come up with new ideas? Again, I suppose it is, but the challenge here is this: ideas are easy—it’s execution that’s difficult. The real work is in taking those ideas and making them real. Put another way, generating ideas—sometimes also known as brainstorming or ideation—is not all there is to creativity. It’s important, to be sure, but it’s only a part of the challenge of employing our creativity. What’s equally (or perhaps more) important is how we follow through and develop and/or implement our creative ideas.

Related to this is another important aspect to creativity that is rarely found in the creativity literature, namely, promoting and communicating our creative ideas to others. If we don’t find ways to share our ideas and effectively communicate and promote them, they often go unrecognized, or worse, unrealized.

In his book, The Myths of Creativity, David Burkus outlines ten myths about creativity and explores the truths behinds those myths. This book is an excellent example of what I consider creativity theory, and should be in the library of anyone interested in creativity or in how we can be more creative. One of the myths explored in this book is the “Mousetrap Myth”, or the idea that “once you have a creative idea or innovative new product, getting others to see its value is the easy part, and that if you develop a great idea, the world will willingly embrace it.” The chapter on the Mousetrap Myth (the final chapter in the book) explores the flaws with the thinking behind this myth. The first is that, quite often, new creative ideas are seen as a challenge and/or a threat to the status quo, and are therefore either ignored or shunned. One of the best examples is Kodak ignoring the potential of digital photography (which they invented) because it challenged their market dominance in film and film processing. Burkus also explores the flawed idea that people with creative ideas often think the idea will speak for itself, and so don’t work at promoting and communicating their ideas. Failure to promote and communicate has led many creatives to watch their ideas either die in a drawer, or be developed and marketed by someone else. As Burkus notes, “We don’t just need more great ideas; we need to spread the great ideas we already have.”

I wrote earlier that I believe the challenge for many of us lies in finding the right model of how creativity and the creative process works so we can apply it in our own fields. I think there is an assumption that people can apply their own expertise or technical know-how to take their ideas to the next level. And while there may be some truth to that, examples and models of taking an idea and shepherding it through the process of turning it into a reality seem to be few and far between.

So where can we look for a model or example of the creative process, and developing and communicating our creative ideas? I think one of the best places to look is Disneyland and other Disney theme parks. More specifically, I believe one of the best models for creativity is found in the design and development of Disney theme parks, a practice better known as Imagineering.

As we’ll examine in more detail in the first part of this book, Imagineering was born from the blending of expertise from a number of fields. Just as the first Imagineers adopted techniques and practices from animation and movie-making to develop the craft of Imagineering, we can borrow (and steal) principles and practices from Imagineering and apply them to other creative endeavors.

In the foreword to Jeff Barnes’ The Wisdom of Walt: Leadership Lessons from the Happiest Place on Earth, Garner Holt and Bill Butler of Garner Holt Productions (the world’s largest maker of audio-animatronics) write: “Disneyland is still the ultimate expression of the creative arts: it is film, it is theater, it is fine art, it is architecture, it is history, it is music. Disneyland offers to us professionally (and to everyone who seeks it) a primer in bold imagination in nearly every genre imaginable.”

If you look at what goes into the design and construction of Disney theme parks and attractions, you discover that Imagineering combines several disciplines often associated with creativity (including illustration, art direction, writing, music and sound design, interior design, lighting design, and architecture) as well as disciplines not typically considered creative such as various engineering fields (structural, mechanical, electrical, and industrial), project management, research and development, and construction management. As a source of inspiration about creativity and the creative process, Imagineering has few peers.

In my search to learn as much as I could about how the Imagineers design and build Disney theme parks and attractions, I’ve identified a set of principles that I believe can serve as a model for the creative process in a variety of fields. I call this set of concepts the Imagineering Pyramid, and it contains principles focused on developing and communicating our ideas. These principles can be applied to developing nearly any type of creative project, from a simple homework assignment to a fully immersive theme park attraction such as Expedition Everest at Disney’s Animal Kingdom.

The rest of this book is divided into three primary parts:

Part One: Pre-Show—Peeking over the Berm presents the origins of “Imagineering” and what the word means, as well as an overview of the Imagineering Pyramid. This will give us a foundation on which we can expand in later chapters. We’ll also look briefly at the idea of having a “vision” and how that fuels the creative process.

Part Two: The Imagineering Pyramid is the heart of the book, and examines fifteen techniques and practices used by Walt Disney Imagineering in the design and construction of Disney theme parks and attractions. Starting with a look at something called the art of the show, this section contains chapters devoted to each block in the Imagineering Pyramid. For each block, we’ll look at examples from the Disney parks, the principles behind each, and how each can be leveraged in other fields.

Part Three: Imagineering Beyond the Berm explores how to apply the principles of the Imagineering Pyramid to a number of specific fields, including game design, instructional design, and leadership and management.

Following Part Three is a “post-show” chapter in which I share some final thoughts and a pair of appendices. Appendix A contains a list of the books, DVDs, and other resources in my Imagineering library (as of this printing, anyway—it doesn’t stay the same for long). Appendix B contains a checklist of questions based on the principles of the Imagineering Pyramid that you can use when developing, evaluating, and promoting your creative ideas.

Lou Prosperi

Lou Prosperi spent 10 years working in the game industry as a freelance game designer and writer, as well as a product line developer at FASA Corporation, where he worked on the Earthdawn roleplaying game. After leaving FASA Corporation, Lou went to work as a technical writer and instructional designer and has been in that role for the last 15 years, providing user and technical documentation and training for enterprise software applications. He currently manages a small team of technical writers and curriculum developers for a small business unit of a large enterprise software company.

Lou has been interested (or obsessed depending on who you ask) in Disney parks since his first visit to Walt Disney World on his honeymoon in 1993. A self-described "Student of Imagineering," Lou has been collecting books about the Disney company, Disney parks, and Imagineering for the last 10+ years. Lou rarely passes up an opportunity to add new books to his Disney and Imagineering libraries, and is nearly always thinking about his next trip to Walt Disney World. Lou lives in Wakefield, Massachusetts with his wife and children.

Don't keep your eye on the ball—keep it on your creative intent!

Staying Focused on Your Objective

In the world “beyond the berm”, focusing on creative intent means staying focused on your objective. We want to make sure that everything we do when developing and promoting our creative projects serves the underlying objective of the project.

Of course, the only way you can stay focused on your objective is to be clear on what that objective is. Like companies and industries and people can lose sight of their mission (as we discussed in Chapter 4), it’s not uncommon for people and companies to lose sight of the true objective of an activity by getting caught up in the details of performing it. For example, if you decide to take up running as a way to get in better shape and lose weight, running isn’t your objective. Improving your physical condition and losing weight are your objectives. Running is the means to that objective.

As another example, the business unit I work for sells enterprise software to the utility industry to help with billing, data management, network and grid operations, and other business processes. A long-held belief of our business is that companies are looking for software that can be customized or tailored to the utility’s specific business processes. That’s changing. Instead of insisting that the software change to meet their business processes, some utilities are willing to change their business processes to accommodate the software they select. One of the reasons is that these companies are realizing that their existing business processes aren’t their real objectives. Those processes were developed at one time to help meet a specific objective, but now these same objectives can also be met in other (often more efficient and less costly) ways. By focusing on their true objectives, these companies become more open to the idea of changing the way they do business.

Vision and Creative Intent

Your project’s creative intent will almost always be strongly based on your vision for the project. Of all of the principles in the Imagineering Pyramid, creative intent is the one most closely related to vision, as it gets to the heart of what you want to accomplish with your project.

One key idea when defining your creative intent is that your objective should be more than to simply create something. The thing you create is simply a vehicle to get your audience to experience something. Your goal isn’t simply to create an example or artifact of your discipline. When designing attractions for Disney parks, the Imagineers’ goal isn’t just to create another attraction. It’s to add a specific experience to the overall show. Whatever field you’re working in, whether it be theme park design, game design, graphic design, or instructional design, your goal shouldn’t be to create an artifact, be it a ride, or game, or illustration, or training course. It’s to create an experience for your audience, whether that audience be an actual audience at a performance or event, a participant in an activity such as a game, a customer or client, or a student in a training class.

As I mentioned earlier, creative intent isn’t something the Imagineers focus on only during the design and construction of an attraction. The Imagineers remain focused on creative intent after the attraction has opened and they continue to focus on it for the life of the attraction. Likewise, if your creative projects have an extended lifespan, it’s important to occasionally evaluate whether or not they’re still fulfilling the objective you had when you first created the project. For example, if you develop a system or process in your work to help solve a problem or a challenge, once it’s been solved you may find that it’s time to retire that process or system. Sometimes we continue to do things long after they’ve served their purpose because those activities become “the way we’ve always done things”. Staying focused on your objective can help prevent you from falling into routines that no longer serve your needs. We’ll look at this idea again in Chapter 22 (Imagineering Management and Leadership).

By the way, if you notice a similarity between creative intent and the art of the show, that’s by design. In some ways, creative intent can be thought of as the smaller-scale cousin to the art of the show. The show is the larger-scale mission, while the creative intent is the specific objective of each part of the show. In an earlier version of the pyramid, the art of the show was one of the foundation blocks and creative intent was discussed as part of that block. I later decided that each of these principles, while related, were different enough to warrant separate discussion.

Focusing on your creative intent—your objective—can also help act as a filter when determining which ideas or concepts to include in your project. What has happened to me on more than one occasion is that when brainstorming ideas for a project I’ll get a great idea—well, what I think is a great idea—but unfortunately, when filtered through the lens of my original objective, I realize that my “great” idea really doesn’t fit as well as I thought it would. This is not unlike how your story can help determine which details to include in your project.

The Pyramid in Practice—Creative Intent

My creative intent with this book is fairly obvious—to explore the principles and practices of Imagineering with a particular focus on how they can be applied to other fields. To this end, I’ve included a variety of examples throughout, as well as separate chapters focused on applying the Imagineering Pyramid to a handful of specific fields, including game design, instructional design, and leadership and management.

Continued in "The Imagineering Pyramid"!

Keep it moving!

The third and final block in the middle tier of the Imagineering Pyramid is called Kinetics, a term that, according to Alex Wright in The Imagineering Field Guide to Magic Kingdom at Walt Disney World, Disney Imagineers use to describe “[m]ovement and motion in a scene that give it life and energy. This can come from moving vehicles, active signage, changes in the lighting, special effects, or even hanging banners or flags that move around as the wind blows.”

Like many of the techniques and tools used by the Imagineers, Kinetics has ties back to the studio’s origins in animation. In animation, kinetics is born from animated figures moving in front of (mostly) static backgrounds. As animator and Imagineer Rolly Crump explains: “Your eye watches what moves. When you’ve got an animated screen going, or when you’ve got an animated cartoon on the screen, you’re not looking at the backgrounds.” The same holds true in the three-dimensional world of Disney theme parks.

There are few truly “still” places in the Disney theme parks. The Imagineers use kinetics to keep the atmosphere in the parks alive, dynamic, and vibrant. In some cases, kinetics takes the form of a single element, such as the sliding doors that open near the top of the Twilight Zone Tower of Terror to reveal the rising and falling elevator cars, or the movement of the tea train as it climbs toward the Forbidden Mountain on Expedition Everest. In other cases, the Imagineers use “layers” of kinetics, such what you see as you move from Fantasyland toward Tomorrowland at Magic Kingdom, with the Astro Orbiter spinning alongside the PeopleMover in the foreground, while the Carousel of Progress building spins in the background. A common feature the Imagineers use to create kinetics are water fountains/features around the parks, such as the jumping fountains and reverse waterfall outside Journey into Imagination with Figment as well as the World Fellowship Fountain at Epcot.

Some other examples of kinetics found in the Disney parks are described in Alex Wright’s Imagineering Field Guides:

- The Red Car Trolley at Disney California Adventure “adds an important kinetic element to the streetscape. Its movement activates the environment and augments the spatial relationships in the architecture”.

- On Alice in Wonderland at Disneyland, “the loop exterior track … [is] a wonderful kinetic element that connects it to the relocated Mad Tea Party”.

- Astro Orbitor at Disneyland serves as a “kinetic beacon into the world of Tomorrowland” while its counterpart Astro Orbiter at Magic Kingdom is “one of the primary contributors to the kinetics of Tomorrowland”.

- Primeval Whirl and Triceratops Spin add kinetics to DinoLand U.S.A. at Animal Kingdom

- At the (now closed) Maelstrom attraction in the Norway Pavilion at Epcot, “the boat peeking out of the attraction provides movement in the courtyard”.

- In Frontierland at Magic Kingdom, kinetics can be seen in the Splash Mountain runoff into the Rivers of America; rafts, the Liberty Belle, and other watercraft moving around and near Tom Sawyer Island; and the passing riverboats, Walt Disney World railroad trains, and Big Thunder Mountain Railroad mine cars.

Kinetics are also often used in the design of wienies. A wienie at the end of an avenue that incorporates movement and kinetics is sure to grab the attention of approaching guests. We looked at examples of these “kinetic wienies” in chapter 10, including the Twilight Zone Tower of Terror, Expedition Everest, and Splash Mountain.

Alex Wright explains that another tool the Imagineers use to keep the Disney parks dynamic and active is what they refer to as BGM (background music), “the musical selections that fill in the audio landscape as you make your way around the park. Each BGM track is carefully selected, arranged, and recorded to enhance the story being told, or the area you have entered.”

Beyond enhancing the kinetics of an area, background music can also serve different roles in different areas. In some areas, background music is inspired by and based on the music and songs from the area’s attractions. For example, the background music in Cars Land at Disney California Adventure includes songs originally written for Mater’s Junkyard Jamboree. In cases like this, the background music serves as a form of audio pre-show and post-show. Guests are first exposed to an attraction through the background music before experiencing the attraction, and then reminded of the attraction after they leave.

In other cases, an area’s BGM is less specific, and intended to help enhance (and blend into) the setting. According to Alex Wright, the background music in Future World at Epcot, for instance, is “less about a specific time or place and more about a mood and the ideas being explored here. It’s chosen by our media designers to reflect the soaring themes and concepts featured in Future World. It can’t be pinned to a particular setting or genre, but completes the effect. You might not even notice that it’s there as you make your away around, but you miss it if it’s not.”

In both examples, the BGM works in tandem with visual kinetic elements to create an active and dynamic environment. For instance, the examples of kinetics in Frontierland noted above also makes use of background music and other sound effects.

Background music can also help in transitions between areas, as I noted in chapter 11, with the gradation of Main Street’s upbeat music into the “growls and howls” of Adventureland, among other examples.

A Dynamic Experience

Kinetics is about keeping the experience dynamic and active. Anything you do to add movement or motion to your project (either literally or figuratively) can help keep it active and “moving”.

Kinetics is especially useful when communicating ideas, such as projects that communicate or convey a message of some sort, or when promoting your projects and ideas. In both cases, kinetics can help keep your audience engaged. For instance, if you’re creating a presentation, using animation (without over-doing it) and other different types of media (music, sound effects, etc.) can contribute to the kinetics of your presentation and help keep your audience’s attention. Graphic design that employs active shapes can also contribute to the kinetics of a presentation or printed materials.

Another way to employ kinetics is through variety—distinguishing specific parts of the overall experience from one another. One way to do this is through using a variety of content and forms of content. Even something as simple as breaking up long blocks of text with bulleted lists or diagrams can help break up the reading experience and make it slightly more dynamic an experience than found when reading walls of words. A good example of employing variety is in instructional design, where we can create kinetic instructional experiences by combining different types of content, such as lectures, demonstrations, exercises, interactivity, and other activities.

Continued in "The Imagineering Pyramid"!

The Imagineering Pyramid!

Each "block" in the pyramid is fully explained in the books, with concrete examples of how you can put Imagineering principles to work for you, right away.

About Theme Park Press

Theme Park Press is the world's leading independent publisher of books about the Disney company, its history, its films and animation, and its theme parks. We make the happiest books on earth!

Our catalog includes guidebooks, memoirs, fiction, popular history, scholarly works, family favorites, and many other titles written by Disney Legends, Disney animators and artists, Mouseketeers, Cast Members, historians, academics, executives, prominent bloggers, and talented first-time authors.

We love chatting about what we do: drop us a line, any time.

Theme Park Press Books

The Unauthorized Story of Walt Disney's Haunted Mansion The Ride Delegate 501 Ways to Make the Most of Your Walt Disney World Vacation The Cotton Candy Road Trip The Wonderful World of Customer Service at Disney Disney Destinies Disney Melodies The Happiest Workplace on Earth Storm over the Bay A Historical Tour of Walt Disney World: Volume 1 Mouse in Transition Mouseketeers Down Under Murder in the Magic Kingdom Walt Disney and the Promise of Progress City Service with Character Son of Faster Cheaper A Tale of Two Resorts I Saw Ariel Do a Keg Stand The Adventures of Young Walt Disney Death in the Tragic Kingdom Two Girls and a Mouse Tale Ears & Bubbles The Easy Guide 2015 Who's the Leader of the Club? Disney's Hollywood Studios Funny Animals Life in the Mouse House The Book of Mouse Disney's Grand Tour The Accidental Mouseketeer The Vault of Walt: Volume 1 The Vault of Walt: Volume 2 The Vault of Walt: Volume 3 Who's Afraid of the Song of the South? Amber Earns Her Ears Ema Earns Her Ears Sara Earns Her Ears Katie Earns Her Ears Brittany Earns Her Ears Walt's People: Volume 1 Walt's People: Volume 2 Walt's People: Volume 13 Walt's People: Volume 14 Walt's People: Volume 15

Write for Theme Park Press

We're always in the market for new authors with great ideas. Or great authors with new ideas. Whichever type of author you are, we'd be happy to discuss your book. Before you contact us, however, please make sure you can answer "yes" to these threshold questions:

Is It Right for Us?

We specialize in books that have some connection to Disney or theme parks. Disney, of course, has become a broad topic, and encompasses not just theme parks and films but comic books, animation, and a big chunk of pop culture. Your book should fit into one (or more) of those broad categories.

Is It Going to Make Money?

There's never a guarantee that any book will make money, but certain types of books are less likely to do so than others. They include: hardcovers, books with color photos, and books that go on forever ("forever" as in 400+ pages). We won't automatically turn down these types of books, but you'll have to be a really good salesman to convince us.

Are You Great to Work With?

Writing books and publishing books should be fun. The last thing you want, and the last thing we want, is a contentious relationship. We work with authors who share our philosophy of no drama and zero attitude, and the desire for a respectful, realistic, mutually beneficial partnership.

If you said "yes" three times, please step inside.