- Visit the Imagineering Graveyard

- Now Sailing: "Skipper Stories" - Tales from the Jungle Cruise

- Coming Soon: The biography of Disney animator Jack Hannah

- Coming Soon: A Haunted Mansion anthology

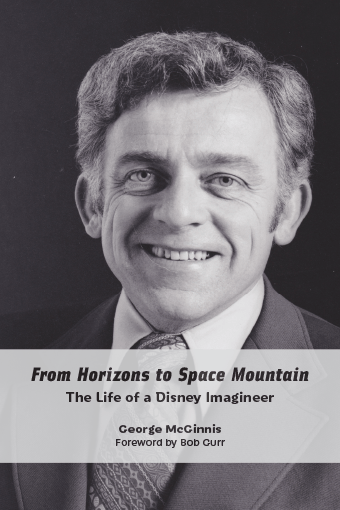

From Horizons to Space Mountain

The Life of a Disney Imagineer

by George McGinnis | Release Date: May 21, 2016 | Availability: Print, Kindle

Walt Disney's Final Imagineer

Walt hired George McGinnis in 1966, and right away George found himself in design meetings with his new boss. For the next three decades, George contributed to such high-profile projects as the new monorails, Epcot's Horizons, and two Space Mountains.

Working alongside Disney luminaries like Marty Sklar, Bob Gurr, and John Hench, George brought his unique background as an industrial designer to the creation of the Mark V and Mark VI monorails, and much of Disneyland and Walt Disney World's Space Mountains. His concept art, often begun on the back of napkins, influenced the final look of many theme park attractions.

George writes in detail of his Imagineering work; his interactions with Walt and many of the company's Imagineers, engineers, and artists; and his career after Disney, which included the design of trolleys for billionaire real estate developer Rick Caruso's upscale California communities.

But George's heart and soul went into one attraction no longer in existence: Horizons. As the manager of Disney's Industrial Design Department, responsible not just for Horizons but for other Epcot attractions, George takes readers truly behind the scenes during what many fans consider Epcot's golden age.

SHARE THE LIFE OF A DISNEY IMAGINEER!

Table of Contents

Foreword

Introduction

An Imagineer's Story

A Chat with George McGinnis

An Imagineer at Work

An Imagineer at Work: Monorails

An Imagineer at Work: Epcot’s Horizons

An Imagineer at Work: Space Mountains

George and The Black Hole

George McGinnis, in Pictures

Foreword

George McGinnis. Let me tell you about George. I never met a designer that exasperated me as much as George. What I did not realize until decades later was that what set my hair on fire at the time was the very characteristic George had that made him probably Walt Disney Imagineering’s finest industrial designer of all time.

No person I ever worked with stuck to his guns over getting every last detail completely correct, staying true to the design requests given to him. He’d show me every single detail and explain why it was so important. As the manufacturing design guy for his projects, I was ready to roll forward while he was continuing to refine his designs. His main boss, Dick Irvine, would exclaim,”George, you’re glossing the goose!”

An example. The WDW 20,000 Leagues submarine was patterned after the dramatic and fantastical Jules Verne-style submarine. George was going to make sure “his” submarine would truly reflect the Verne concept. It’s just a ride vehicle to me, but not to George! He added a most elegant brass helm and fancy wheel, totally unneeded on a ride. Irvine said no, and I grabbed the parts and confiscated them to my home. I still have them today … my personal monument to George’s unyielding honor to “just do it right”.

And doing it right is what George unfailingly pursued during his entire career with Disney, his work on Rick Caruso’s trolleys and beyond. When I visit Glendale’s Americana today, I still stop to admire George’s fantastical, beautiful (and correct) trolley, another wonderful monument to his superb design integrity.

George’s autobiography will be a joy to everyone who values authentic design. He shares tales and details—all in the most thorough manner—through his revealing text and illustrations. And to those who wish to pursue Imagineering, in fact, any significant creative career, this is your guiding treasure.

Introduction

Industrial designer George McGinnis began his career at Walt Disney Imagineering in 1966. His senior project at the Art Center College of Design, a working model of a futuristic high-speed train, attracted the attention of Walt Disney. George was invited to Imagineering by Walt, who showed him the WEDway PeopleMover system in development. Walt proceeded to introduce George to Dick Irvine, President of Imagineering, who invited George to become an Imagineer.

George’s first assignment was to design miniature transportation models for the Progress City display for the Carousel of Progress attraction that opened at Disneyland in July 1967. He was also responsible for concept design of both the Mighty Microscope for the Disneyland attraction Adventure Through Inner Space and the Saturn-style “winged rocket with boosters” for Disneyland’s Tomorrowland Rocket Jets (1967). From 1967 to 1971, George designed WEDway PeopleMover trains and parking lot shuttle vehicles for Walt Disney World. In 1971, he became a show designer, involved with such major projects as Space Mountain for both Walt Disney World (1975) and Disneyland (1977). A year later, in 1978, he worked on the concept designs for the robots in Disney’s The Black Hole motion picture.

In 1979, George became manager of Industrial Design for Epcot and later project show designer for the Horizons Pavilion. In addition, he also designed SMRT-1 and the Astuter Computer Revue for the Communicore Pavilion. From 1983 to 1987, George designed the Mark V monorail train for Disneyland, which debuted in 1987. Following that, George contributed design ideas for the Magic Kingdom attraction Delta Dreamflight/Take Flight, designed the Walt Disney World Mark VI monorail, and designed tram vehicles for the Disney-MGM Studios Backlot Tour.

Between 1990 and 1995, George brought his skills as a show designer to several projects for Disney theme parks around the world: boat vehicles for Splash Mountain at Tokyo Disneyland and the Magic Kingdom, Indiana Jones Adventure ride vehicles for Disneyland, the Space Mountain ride vehicle concept for Disneyland Paris, river boats, safari vehicles, and a “steam” locomotive and cars for Disney’s Animal Kingdom at Walt Disney World. Since retiring from Imagineering in 1995, George has continued to work for Disney as a consultant on the Rocket Rod concept vehicle for Tomorrowland, river rafts for Animal Kingdom, and California Adventure.

In addition to his post-retirement work for Disney, George designed trolley cars for real estate developer Rick Caruso. Both trolleys are popular attractions at The Grove and the Americana, two of Caruso’s upscale residential/shopping communities in California.

George McGinnis

George McGinnis is a retired Disney Imagineer, the last Imagineer personally hired by Walt Disney, in 1966. His three-decade career with the company involved such high-profile projects as the Mark V and Mark Vi monorails, Horizons, and Space Mountain.

George takes on Marty Sklar's challenge of designing the "largest special effect ever" for Horizons.

Epcot opened in 1982 and Horizons was scheduled to open the next year. This one pavilion now had the use of WDI’s best artists, writers, and designers who had created Epcot. General Electric’s representatives on the team had experience working with Disney on past shows. Early on, working names for the pavilion were Century III and FutureProbe. Of the latter, Ned Landon, GE representative on the Horizons Imagineering creative team, said “Not bad. But we always thought it had a rather uncomfortable medical connotation.” Ned was comfortable with the name Horizons. Quoting Ned:

There always is a horizon out there. If you try hard enough, you can get to where it is—and when you do, you find there’s still another horizon to challenge you, and another beyond that.

The Horizons show would pick up the story from the Carousel of Progress by presenting that show’s memorable family one generation older. The parents are now grandparents communicating with their kids spread the world over and into space. The story sequenced through past, present, and future. The “past” was presented as “Looking Back at the Future”, as science fiction writers had portrayed it. The “present”, viewed on giant Omnimax screens, used current science images from the space shuttle lifting off to views of molecular structures and DNA by filmmaker Eddy Garrick. The “future” would let us visit the family members in habitats and environments that are still a dream in scientists’ minds. The father and mother keep in touch with their children in these distant places via holographic devices.

I had the pleasure of joining Ned Landon when he gave Jack Welch, by then the new GE chairman, a walking tour of the nearly completed pavilion. Jack immediately recognized the father and mother when we reached the “future” scenes. He wanted to know why we were using the characters from the old Carousel Theater. Ned explained the story’s premise and from then on the warmth of the story became evident to Jack.

The late Claude Coats, one of the original WED/WDI art directors, was show designer directing the initial concept (a most prolific designer, Claude got the first licks in on most of the Epcot pavilions). Claude worked with industrial designer Bob Kurzweil and architect Bill Norton on the first ride layout. Collin Campbell developed the wonderful early scenes with Albert Robida’s vision of the future on to the Art Deco home with robots vacuuming, cutting hair, and cooking.

Viewing all this from the vehicle required a version of the Omnimover to effectively put you into the scenes. I recall that Gil Keppler and I built the full-size mockup for testing in just thirteen hours. (John Horney, WDI artist, skilled at caricatures, sketched Claude, Marty, the late John Hench, and me in the mock-up vehicle. He gave us all a good laugh.) Guests may have wondered where they would go if the ride stopped, especially when hanging out in space. If an evacuation was called for, which seldom happened, a door would pop open behind the guests and an operator would guide them to an exit.

The Largest Special Effect Ever

The ninety-foot Omnimax theater had to be positioned before the building design could be completed. Architect George Rester formed the “spaceship” building and the ride layout conformed to Rester’s pavilion outlines from then on. The huge Omnimax theater was beneath the center of the pyramidal form. Early on, Marty Sklar had stopped me in the hall and asked me to see whether an IMAX theater could be adapted to the ride.

In the past I had been playing with the idea of an Omnimax simulator experience that wasn’t going anywhere. Here was my opportunity to use it. I laid out a three-screen arrangement that allowed vehicles to have a continuous show through two circuits around a triangular core, housing three projection rooms. I was able to hide the load/unload at the base of this tower. In my mind the Omnimax theater would be the big ending experience, but the writer’s story used it instead to tell the “present” with all the amazing advances in science.

Marty then asked me to come up with a “wienie” (a Walt term for something that draws your attention) for the ending. I developed the traveling-screen concept, which allowed four guests to “Choose Their Future” by voting on touch panels. The choices were video simulations of travel through environments we had visited: desert, undersea, and space, ending up back at the FuturePort where our journey began. Engineer Marty Kindel began working out the complicated logistics that would enable each car to see a different environment.

Continued in "From Horizons to Space Mountain"!

George recalls getting started with one of the biggest challenges of his Imagineering career: Walt Disney World's Space Mountain.

Roger Broggie Sr. headed up the engineering side of WED and played an important part in the development of Space Mountain. Roger’s genius over the years was in getting things done for Walt. This contributed to Bill being allowed to change the design concept that had been used on the Matterhorn to the more efficient gravity ride. Not everyone in WED’s management was happy that Roger was bringing the design and manufacturing of Space Mountain in-house instead of continuing with the effort at Arrow Development.

The first track design Bill and I worked on was to be in Disneyland. There was a space in Tomorrowland, the perimeter of which was described by substructures that could not be removed. For a while we struggled with a building configuration that would fit in Tomorrowland and enclose the two-track system.

I built a small wire model of the track. When it was shown to Dick Irvine, the president of WED, his comment was, “George, can’t it be more pyramidal in form?” Of course at this presentation it had no “mountain” cover and it was practically a “cube” of wire. My early sketches on the exterior attempted to retain a mountain shape as on John’s sketch, by letting the outer curves of track protrude from the mountain as were also on John’s sketch.

Events related to sponsorship at Walt Disney World changed everything. RCA sold its computer business to Univac and would not be sponsoring John Hench’s Alice in Computerland (which would be reborn as the Astuter Computer Review at EPCOT Center for Sperry Univac), so RCA was given the option of sponsoring Space Mountain.

Roger Broggie, whose engineering department I was loaned to after six months at WED, was now serious about Space Mountain. Roger sent me to see John Hench about the show aspects of the mountain. John described what he wanted: the load/unload areas to be at the back and pre-show and post-show spaces along a moving belt going in and out.

The Post-Show

I did renderings and layouts of the show spaces and a group of us traveled to New York for a presentation to Robert Sarnoff, then chairman of RCA, for approval. These were early concepts and much would change as Bill and I integrated show with track.

The late Claude Coats contributed to this huge effort and this began an unofficial competition that ran through several projects over the years. Claude was prolific in his output. X. Atencio, a Disney artist and writer, once described him as a person you wouldn’t find “hanging around the water cooler”.

Claude tended to work alone and was aided by model builders extensively. I built my own models and I used them to develop designs. On the return trip from New York, we were in the upper level of a Boeing 747 and were discussing the post-show. I sketched out a post-show concept of hexagonal spaces, which would frame the scenes of RCA’s Home of the Future. To my surprise, Claude had a model builder on it the next morning. (The modeler was Rick Harper, a recent graduate of Cal Arts film school. He went on to do great things, including the film for the France Pavilion.)

The post-show story was of family members, in each room of the home, busy communicating via TV screens or learning through RCA’s new VideoDisc. In detailing the rooms, I created ridiculously large screens assuring a future look. They still look large, but not as impressive now that the “future” has arrived.

Before opening day, RCA requested that their famous Nipper be represented in the pre-show. I designed a classic flying saucer for RCA’s fox terrier mascot, popular from the earliest days of recording. Nipper was the first to greet RCA’s guests as they descended the entrance ramp that led to the long tunnel. The tunnel passed under the Walt Disney World railroad tracks leading on through to the pre-show to the vehicle loading area.

“We Can Build It”

Locating the mountain at Walt Disney World required track changes to incorporate show spaces. One change that had been suggested earlier was the strobe tunnel. Leaving the load area, the vehicles would dive into a long tunnel of blinking strobes and light panels, inspired by a similar tunnel in the movie 2001: A Space Odyssey. My purpose in suggesting the tunnel, besides the special effect, was to have the chain lift pointed in the opposite direction. That would allow the front of the mountain to slope away without the high point of the track protruding to the front. This idea was conceived when we were trying to fit Space Mountain into Disneyland, but now a larger building was going to give us more than enough room for track and show.

I don’t remember deadlines when I was doing the concepts, but I was always ready to show my work. About the time Roger Broggie sent me to see John Hench, an office opened up in the main building and I was moved. This was a memorable day—Orlando Ferrante and Fred Tatum, two members of WED supervision, welcomed me by stomping on the floor overhead. These are big fellows and I’m sure it tested the lift-slab structure we were in to near destruction. Then they came down to say hello.

I was now situated in an area that was called Show Design. When Dick Irvine had sent me to Roger Broggie’s MAPO Engineering, he said, “You’ll be back.” Five years later his promise was fulfilled. Nearby was a small conference room next to Dick Irvine’s office (eventually called Edie’s Conference Room, after Dick’s wonderful support person, Edie Flynn). It was interesting that when I was called without warning to “show and tell” there would be more than just Dick Irvine, John Hench, and Marty Sklar reviewing my work.

When I showed the artwork and plans for the strobe tunnel, it was Marc Davis who put his seal of approval on it. Bill Martin, the senior show designer for WED, would sometimes sit in and make constructive remarks. I remember the day he suggested Glenn Durflinger take over the production of Space Mountain’s architectural construction drawings. Glenn was an experienced architect and the right person for the task. In another meeting with John Hench and Don Edgren, WED’s chief engineer, I presented the chain-lift Space Port concept model. With its high walls and robotic arms grasping the InterPlanetary Explorer [spaceship], I wondered if it would survive. Don said, “We can build it.” Those are words all show designers like to hear from engineers.

Continued in "From Horizons to Space Mountain"!

About Theme Park Press

Theme Park Press is the world's leading independent publisher of books about the Disney company, its history, its films and animation, and its theme parks. We make the happiest books on earth!

Our catalog includes guidebooks, memoirs, fiction, popular history, scholarly works, family favorites, and many other titles written by Disney Legends, Disney animators and artists, Mouseketeers, Cast Members, historians, academics, executives, prominent bloggers, and talented first-time authors.

We love chatting about what we do: drop us a line, any time.

Theme Park Press Books

The Unauthorized Story of Walt Disney's Haunted Mansion The Ride Delegate 501 Ways to Make the Most of Your Walt Disney World Vacation The Cotton Candy Road Trip The Wonderful World of Customer Service at Disney Disney Destinies Disney Melodies The Happiest Workplace on Earth Storm over the Bay A Historical Tour of Walt Disney World: Volume 1 Mouse in Transition Mouseketeers Down Under Murder in the Magic Kingdom Walt Disney and the Promise of Progress City Service with Character Son of Faster Cheaper A Tale of Two Resorts I Saw Ariel Do a Keg Stand The Adventures of Young Walt Disney Death in the Tragic Kingdom Two Girls and a Mouse Tale Ears & Bubbles The Easy Guide 2015 Who's the Leader of the Club? Disney's Hollywood Studios Funny Animals Life in the Mouse House The Book of Mouse Disney's Grand Tour The Accidental Mouseketeer The Vault of Walt: Volume 1 The Vault of Walt: Volume 2 The Vault of Walt: Volume 3 Who's Afraid of the Song of the South? Amber Earns Her Ears Ema Earns Her Ears Sara Earns Her Ears Katie Earns Her Ears Brittany Earns Her Ears Walt's People: Volume 1 Walt's People: Volume 2 Walt's People: Volume 13 Walt's People: Volume 14 Walt's People: Volume 15

Write for Theme Park Press

We're always in the market for new authors with great ideas. Or great authors with new ideas. Whichever type of author you are, we'd be happy to discuss your book. Before you contact us, however, please make sure you can answer "yes" to these threshold questions:

Is It Right for Us?

We specialize in books that have some connection to Disney or theme parks. Disney, of course, has become a broad topic, and encompasses not just theme parks and films but comic books, animation, and a big chunk of pop culture. Your book should fit into one (or more) of those broad categories.

Is It Going to Make Money?

There's never a guarantee that any book will make money, but certain types of books are less likely to do so than others. They include: hardcovers, books with color photos, and books that go on forever ("forever" as in 400+ pages). We won't automatically turn down these types of books, but you'll have to be a really good salesman to convince us.

Are You Great to Work With?

Writing books and publishing books should be fun. The last thing you want, and the last thing we want, is a contentious relationship. We work with authors who share our philosophy of no drama and zero attitude, and the desire for a respectful, realistic, mutually beneficial partnership.

If you said "yes" three times, please step inside.