- Visit the Imagineering Graveyard

- Now Sailing: "Skipper Stories" - Tales from the Jungle Cruise

- Coming Soon: The biography of Disney animator Jack Hannah

- Coming Soon: A Haunted Mansion anthology

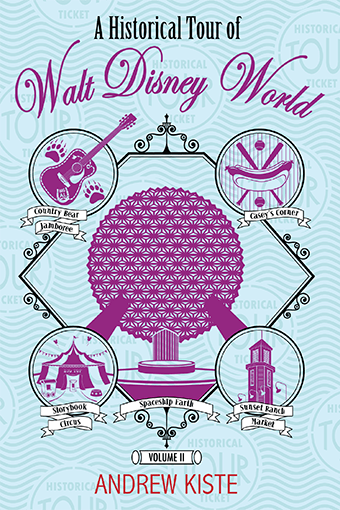

A Historical Tour of Walt Disney World

Volume 2

by Andrew Kiste | Release Date: June 1, 2016 | Availability: Print, Kindle

Deep Dive into Disney History

The Imagineers are no slouches when it comes to history. Many of the attractions and shows they create are steeped in it. But the history is hidden. In this second of Andrew Kiste's best-selling "tours", you'll dig deeply into the back stories of five Walt Disney World favorites.

Have you ever wondered who's the Casey in Casey's Corner? Why its baseball theme, as well as the circus theme of Storybook Circus, are such powerful symbols in American culture? How the many scenes in Spaceship Earth deliver a surprisingly rich, detailed timeline of civilization to astute guests—but only if you first know what the Imagineers knew when they created it?

You'll learn all that and more on your historical tour of:

- Spaceship Earth: Earn an honorary degree in world history as you absorb, in depth, the historical background of each scene in Epcot's centerpiece attraction.

- Country Bear Jamboree: Trace the lineage of these singin' bears back to Walt's plans for his never-built Mineral King Resort.

- Casey's Corner: Learn the story of baseball over hot dogs in this Magic Kingdom restaurant where it's always the bottom of the ninth.

- Sunset Ranch Market: Brush up on World War II at Hollywood Studios' open-air food court.

- Storybook Circus: Take in the history of the American circus and how this new area of Fantasyland puts you squarely under the big top.

THE HAPPIEST HISTORY CLASS ON EARTH IS IN SESSION!

Table of Contents

Introduction

Country Bear Jamboree

Casey's Corner

Storybook Circus

Spaceship Earth

Sunset Ranch Market

Afterword

Selected Bibliography

Introduction

When Walt Disney created Disneyland during the 1950s, he opened it as a man who had red, white, and blue running through his veins. In fact, when he dedicated the park on its opening day in 1955, Walt explained that “Disneyland is dedicated to the ideals, the dreams, and the hard facts that have created America, with hope that it will be a source of joy and inspiration to all the world.”

Walt, of all people, had a reason to be proud of his country as an American patriot.

His father, Elias Disney, worked as a carpenter, and was hired to help build the temporary structures that would house the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition, better known as the Chicago World’s Fair, which served as a way for America to showcase its industrial strength and cultural dominance over the rest of the world.

As a boy, young Walter moved to Marceline, Missouri, which had sprung up in the late 1800s along the Santa Fe Railroad line. During the late 1800s and early decades of the 1900s, the railroad served as the backbone of American economics, acting not only as a method of long-distance transportation for passengers, but also as the main method through which raw materials and products were transported across the country. Many of the towns through which the railroad ran and the surrounding areas provided resources and raw materials to help the railroad function at full capacity, as well as any goods that those traveling along the railway may have required, something that Walt participated in during his teenage years in Kansas City, selling newspapers and snacks to railroad patrons. Walt’s love of trains developed at this young age, and would later manifest itself when he would build the Carolwood Pacific Railroad in the backyard of his home, and later, the passenger railroad that would encircle Disneyland.

Young Walt was also employed by his father to deliver newspapers after the family moved to Kansas City, leading to a transition in Walt’s life from the backbone of American industry working on the railroad to delivering newspapers, the lifeblood of American culture in the era of his youth. While Walt often discussed the hard times he endured twice daily delivering the Kansas City Star for his father, including the bitter cold of Midwest winters and the utter exhaustion from beginning his deliveries before dawn, he also recognized that the experience developed in him a strong work ethic and helped him to become the man he eventually would become.

During the latter days of Walt’s teenage years, he was finally able to escape the growing dullness of the Midwest and his father’s high expectations. After three of Walt’s older brothers, including Roy, joined the armed forces in 1917, when America entered the First World War, Walt also desired to enlist to defend the country he loved and follow in his brave brothers’ footsteps. Being only sixteen, Walt was too young to enlist in the infantry forces, and instead applied to become an ambulance driver for the American Red Cross. When Walt and a friend were rejected, he changed his birth date on his passport to 1900, instead of 1901, explaining to his parents that he didn’t want his grandchildren to think he was a “slacker” for not supporting his country in the war. Elias and his wife, Flora, finally relented, and Walt traveled to Chicago, where he was stationed, awaiting deployment.

Before he could be deployed overseas, Walt contracted influenza during the epidemic of 1918 and had to return home to be cared for by his parents. When finally he returned to Chicago, the war had ended, but he was chosen to be sent to France to help the nation recover in the war’s aftermath.

While stationed in France, Walt was employed as an ambulance driver, but did very little transporting of the sick or injured. Instead, he ran errands for the hospitals and those who were enlisted, as well as providing tours of the region for visiting dignitaries. During downtimes, Walt drew cartoons of a doughboy character he had created, a young soldier fighting on behalf of the Americans against the regime of German Kaiser Wilhelm II.

After a year in France, Walt returned to America where he would soon begin his work in animation. Serving his nation as a military representative, even though he did not fight in battle, helped to deepen a sense of American pride in the young Midwesterner.

Walt carried his American pride into adulthood, making it a key part of Walt Disney Productions. During the 1940s, Walt would once again have the opportunity to serve his nation when he turned the Disney studio into a propaganda production facility, employing ninety percent of the studio’s animators and artists in the creation of training films for the military and animated shorts to educate the American public about ways to support the war effort.

For example, the animated short Food Will Win the War educated Americans about food conservation, as well as helping to encourage farmers of their significance in defeating the Axis Powers of Germany, Italy, and Japan during World War II. Another short film, Education for Death, showed a young German boy, Hans, as he grows from childhood innocence and, after being indoctrinated by Nazi ideology, becomes a Nazi soldier, ultimately dying for the German cause in war. A more lighthearted look at the war featured Donald Duck in numerous propaganda films, including Der Fuehrer’s Face, which portrayed Nazi Germany and its radical practices in a ridiculous manner, encouraging Americans not to take the Germans too seriously while showing them how thankful they should be that they lived in a nation of freedom.

Disney was also called upon by the United States government to help increase good will toward the country in Latin America. In the early 1940s, Walt Disney and some of his best artists and animators were sent to Latin and South America, where they made observations of and created art based on Latin American landscapes, peoples, and customs. Out of this trip came two important, but lesser-known Disney animated films, Saludos Amigos and The Three Caballeros, released in 1942 and 1944, respectively.

Many of Disney’s animated shorts and feature films, as well as numerous live-action feature and television films focused on American themes, as well. For example, in 1948 Disney released Melody Time, featuring two animated shorts that were based on historical American legends: Johnny Appleseed and Pecos Bill. In 1957, Disney released Johnny Tremain to theaters, which would later air on The Wonderful World of Disney television anthology series. The film, based on the novel of the same name, followed a young man living in Boston during the events of the American Revolution.

However, the most popular of Disney’s history-based projects was Davy Crockett: King of the Wild Frontier, a five-part miniseries that aired on his Disneyland anthology television series from 1954–1955. This show helped to bring the coon-skin cap into the American consciousness, and even made its way into Disneyland when it opened in 1955 through the introduction of the Davy Crockett Frontier Museum, featuring wax figures of many of the show’s popular characters as well as the Davy Crockett Explorer Canoes and the Mike Fink Keel Boats, which allowed guests to navigate the Rivers of America surrounding Tom Sawyer Island.

One of the most interesting ways Walt Disney contributed to Americana, however, was also significant to the history of The Walt Disney Company and Disney theme parks throughout the world today.

From April 22, 1964, until October 17, 1965, the New York World’s Fair was held in Flushing Meadows Park in Queens, New York. While many different nations contributed to world’s fairs, these expositions were generally meant to glorify the host nation and its accomplishments and technological innovations. Three American companies (General Electric, Ford, and Pepsi) and the State of Illinois called upon Walt during the planning stages for the fair. Walt and his crew of Imagineers focused on highlighting American ingenuity, the American dream, and American liberty for three of these pavilions.

In the Ford Magic Skyway attraction, Walt himself narrated a ride through history, highlighting man’s past, the invention of transportation, and the future of vehicles. Walt’s partnership with Ford featured a fitting dynamic, as both Henry Ford and Walt Disney were true American visionaries, focusing on how they could improve the lives of Americans during the times in which they lived.

The second pavilion, General Electric’s Carousel of Progress, highlighted American ingenuity and the progress of technology, as a family pursued the American dream from the late nineteenth century through the near future.

The third pavilion, sponsored by the state of Illinois, highlighted the most famous of the state’s historical figures who exemplified American freedom and liberty, Abraham Lincoln.

The fourth pavilion, hosted by Pepsi as a salute to UNICEF, featured the now classic attraction, It’s a Small World, and worked to instill a message of acceptance, tolerance, and love between the nations of the world.

These four attractions provided Disney with the finances and motivation to develop the fledgling technology of audio-animatronics, which would soon be used in his growing theme park empire.

Walt’s newest project, the Experimental Prototype Community of Tomorrow, more commonly known as Epcot, would never come to fruition in its original concept due to Walt’s death in 1966. However, in addition to his goals of achieving the utopian ideals of city planning and eradicating the problems of slum living and infrastructure and transportation issues, Walt understood what it meant to be an American. In everything that he did, he attempted to improve upon things, to make life better for himself, his children, and the families of America.

As I researched the topics of this book, I realized that each of them, while not necessarily influenced by Walt on a personal level, were influenced by the ideas and American beliefs of Walt Disney. The attractions and venues discussed in this volume reflect the American ideals and beliefs that Walt held dear:

- The Country Bear Jamboree was to be an entertainment offering at the Mineral King Ski Resort that Walt had initially planned on developing in the Sequoia National Forest in 1965.

- Casey’s Corner, a small counter-service restaurant located on the west side of Main Street, U.S.A., in Walt Disney World’s Magic Kingdom, is based on the animated segment “Casey at the Bat” from the 1946 package film Make Mine Music, and reflects the turn-of-the-twentieth-century sports culture that Walt may have experienced while living in Marceline.

- Storybook Circus, a mini-land attached to New Fantasyland in the back of the Magic Kingdom, harkens back to family entertainment, as well as influence from numerous circus-themed shorts and films produced by Disney, including Dumbo and “Bongo”, which was a part of the package film Fun and Fancy Free.

- Spaceship Earth, the attraction located inside the iconic geodesic sphere located at the entrance to Epcot, represents the American spirit of innovation and improvement of technology, even while looking at key points of human history, beyond that of the USA.

- Sunset Ranch Market, an outdoor food court located on Sunset Boulevard in Disney’s Hollywood Studios, and themed around World War II, features different insignias designed by Disney animators to represent different units of the United States military during that war.

While Walt Disney has been gone for almost fifty years, his legacy of innovation, pursuing the American Dream, remembering and honoring our past, and appreciating the freedom and liberty we have in our nation continues to live on in numerous films, lands, and attractions as the result of his effort to showcase the best of America.

Andrew Kiste

Andrew Kiste teaches high school history in Greensboro, North Carolina, and has loved both Disney World and writing for as long as he can remember. He was raised in Grand Rapids, Michigan, and made many family trips to Walt Disney World over the years. Always interested in American and world history, he found himself gravitating to the rides and attractions that centered around historical topics, such as the Hall of Presidents, Pirates of the Caribbean, Walt Disney’s Carousel of Progress, Spaceship Earth, and The American Adventure.

After a lengthy trip to Walt Disney World while still in high school, Andrew began doing research online about the park and frequenting fan blogs, forums, and websites. Some time later, he published his first historical article about a Disney attraction, and then his first book, A Historical Tour of Walt Disney World: Volume 1. From there has not looked back.

Batter up! Grab a hot dog and a cold Coca-Cola in Casey's Corner, right on Main Street, U.S.A., and experience the history of the America's favorite pastime, baseball.

Originally opened as the Coca-Cola Refreshment Corner in 1971, the restaurant located at the corner of Main Street, U.S.A. and the park hub was refurbished and renamed Casey’s Corner in 1995. The eatery, one of the most popular in the park, sells “designer hotdogs”, including chili-cheese dogs, corn dog nuggets, and the barbecue slaw dog. While there are still a few slight nods back to the Coca-Cola Refreshment Corner through the use of Coca-Cola signage and advertisements, the theming of the restaurant leans heavily toward the game of baseball, specifically around the turn of the century.

As guests approach the restaurant from the hub, they find an outdoor seating area across the sidewalk against the wrought-iron fence surrounding the gardens of flowers, which is often occupied by the families of ducks that frequent this area of the Magic Kingdom. These tables, covered by red and white umbrellas, offer additional seating. A pianist playing ragtime piano often performs beneath the canopy of the restaurant. Attached to the canopy, on the corner of the building, is the sign for the restaurant, a large red “C” outlined by clear electric light bulbs, with the restaurant’s name, Casey’s Corner, printed in blue letters along the curves of the sign. The large red C is shaped in the same style as that on the opening scene for the animated short in the segment from Make Mine Music. Inside the hollow part of the sign is a figure of a baseball player swinging at a pitched baseball. The baseball is hollow on one side, and on windy days causes the figure to spin in a circle as though the player is striking out, like the baseball hero in Thayer’s poem. A six-foot-tall wooden figure of a baseball player wearing a white uniform with vertical blue stripes and the restaurant’s name scrolled across his chest welcomes guests as they walk into Casey’s Corner through its Main Street, U.S.A. entrance.

The white entrance doors show the opening date of the restaurant, engraved on a baseball, as 1888. This date fits into the overall story of the town of Main Street, U.S.A., but also connects back to the year that Thayer published “Casey at the Bat”. Upon entering the small counter-service restaurant, guests find the ceiling painted red, with red-and-white striped wallpaper. Above the service counter is an ornate wooden awning, similar to something that would have hung over the box office or concession stand of a baseball stadium in the 1880s. Stained glass lamps featuring the Coca-Cola logo hang from the ceiling, making the room feel even more a part of the era it is meant to represent.

The menu, attached to the wooden awning over the counter, features the fateful scene from the Disney short, with Casey standing haughtily on the left while the opposing pitcher stands on the right in mid-pitch. The room is decorated with framed photographs and magazine advertisements featuring baseball players and ladies in Victorian dress drinking Coca-Cola out of glass bottles. A wooden cabinet on the left wall of the room, which serves as a condiment station for the hot dog fixin’s and other supplies, including napkins and straws, is decorated with baseball-themed props, such as a metal basket full of baseballs and cardboard popcorn buckets. Similar supply cabinets throughout the restaurant feature other memorabilia, including beer steins emblazoned with baseball team logos, glass bottles of Coca-Cola, baseball caps, and glass jars full of peanuts.

To the right of the main entrance of Casey’s Corner is the small main dining room. Above the entryway into this dining room is a large white banner reading “BALL GAME TO DAY”, beneath which hang five small American flags featuring a circular pattern of thirteen stars. This flag is out of place here, as the flag of the United States in 1888 would have been a similar pattern of stars in the rows that we have today, but would have forty stars for the forty states, rather than the thirteen stars on the flag that was adopted in 1777. The flag that flies atop the building on Main Street that the restaurant is located in is actually a more accurate representation of what the flag would have looked like in the period of the restaurant’s story: it features forty-five stars organized into six rows, leading us to believe that our visit to the restaurant is taking place sometime between 1896 and 1907, which is when the forty-five star flag would have flown. The flag would not have forty-six stars until 1907 when Oklahoma became a state. This flag may place the restaurant in the year 1902, as this is the date referenced in the animated short when Colonna explains that Casey is “the Sinatra of 1902”.

The main dining room has red painted walls featuring photographs, advertisements, portraits, and artist renderings of the game of baseball during America’s Victorian era. A wooden chair rail stretches about three-and-a-half feet off the ground with square wainscoting below, adding to the Victorian elegance of the restaurant. Felt banners and pennants hang from the crown moulding along the ceiling of the room commemorating different baseball clubs from the turn-of-the-century, including St. Louis, Lehigh, Downer, and Lockport. Red and white tables with decorative metal chairs litter the room, sitting atop black-and-white tiled floors. Electric lamps hang from the ceiling featuring upturned glass fixtures and Tiffany lampshades.

On the left hand wall of the room is a scoreboard that seems to just be another decoration fitting in with the baseball memorabilia. Astute observers will realize that the scoreboard actually references the poem and Disney short: the teams on the scoreboard at Republic Field are listed as VISITORS and MUDVILLE, with Mudville trailing by two runs. The ninth inning scores list both teams as having scored zero runs; a number is only placed on a scoreboard in baseball after the completion of the inning. As a result, we can assume that the scoreboard is showing the final score of the game, referencing Casey’s failure to win the game for his team in the bottom of the ninth inning. Also, the scoreboard explains that the game is taking place at Republic Field, although neither the animated short nor the original poem named the field on which the game was played. Instead, the field’s name listed on the scoreboard in the restaurant is likely a reference to the full title of Thayer’s poem, “Casey at the Bat: A Ballad of the Republic Sung in the Year 1888”.

Continued in "A Historical Tour of Walt Disney World: Volume 2"!

Each scene in Spaceship Earth, when fully "unpacked", presents a fascinating, in-depth mini-course about a pivotal time in world history, such as this one, the burning (actually, the third burning!) of the Library of Alexandria. If you don't recognize the name, you certainly recognize the smell...

After displaying the glories and strength of ancient Rome, the following scene shows its decline. Interestingly enough, the scene representing the fall of Rome did not actually take place in Rome itself, but, rather, in the city of Alexandria, in Egypt. Amidst one of the favorite smells of many Disney fans, simply known as “Rome Burning”, Dench explains that the Roman Empire fell and that much of the learning that was discovered during the time of the ancient Greeks and Romans was destroyed when the Library of Alexandria is burned. Originally built to house the wealth of Egypt when Alexander the Great established the capital city of his Hellenistic Empire at the mouth of the Nile River after conquering Greece and Egypt in 331 BC, the library had varying amounts of papyrus scrolls (books as we know them had not yet been invented), with some estimates as high as 400,000 scrolls in the library’s collection at any given time.

While the attraction portrays the burning of the great library as being a result of the fall of the Roman Empire, or even leading to the empire’s fall, neither is the case. In fact, the attraction doesn’t even specify which burning of the Library of Alexandria is being portrayed. There were actually three different instances in which the library was destroyed. The first burning occurred in 48 BC when, in an attempt to conquer Alexandria, Julius Caesar burned the Egyptian ships anchored in the harbor. The fire spread unintentionally from the ships to the library, causing all documents in the collection to be destroyed. However, this is not likely to be the fire depicted in the attraction, as Caesar’s accidental destruction of Alexandria occurred eighty years prior to Caligula’s rule over Rome depicted in the prior scene.

The second burning of the Library of Alexandria took place in 391 AD and was brought about by Theophilus, the patriarch of the Coptic Christian Church of Alexandria. Attempting to establish the power of the church in Egypt, Theophilus decided to destroy all examples of pagan religion, including the various shrines and temples to Egyptian and Roman gods that littered the city. One of these temples, the Temple of Serapis, held ten percent of the scrolls that made up the library’s collection. In order to eradicate the city of all un-Christian influence, he burned the interior of the temple, destroying many of the texts in the process. He then established a Christian church in place of the Temple of Serapis, using the burned-out building as the shell for the new church. While this may be the historical event described by Dench, it is unlikely, due to the fact that she groups the library’s destruction with the fall of the Roman Empire, which occurs approximately eighty-five years after Theophilus’ destruction of the Temple of Serapis. Also, his destruction of the pagan temple did not destroy all of the records; ninety percent of them remained unscathed in the main building of the library nearby.

The most likely event as described by Dench occurred in 640 AD, one hundred sixty-four years after the fall of the Roman Empire in 476 AD. The two events are not actually linked; the power of the Roman Empire was no longer a threat, and as a result, it made the burning of the Library of Alexandria possible without opposition. In 640 AD, Muslim armies from the Arabian Peninsula invaded and conquered Egypt, taking it from the fairly weak Byzantine Empire. The conquering officer of the Muslim armies, Amr ibn al-As, wrote to the caliph of the Islamic Empire, Umar Ibn Al Khattab, requesting instruction on what to do with all of the texts stored in the Library of Alexandria. Umar responded famously that the texts “will either contradict the Koran, in which case they are heresy, or they will agree with it, so they are superfluous”. As a result, he ordered the library to be destroyed and the texts burned. Arabic legend says that there were so many scrolls that it took six months to burn all of them, and that the burning paper was used to heat the baths of Alexandria for the invading armies.

This is likely the historical event that the scene represents, especially within the context of the following scene. The burning of the library in 640 AD is not a result of Rome’s fall, as it occurred centuries after the end of the Roman Empire. After being sacked by the nomadic Huns in 476, Rome ceases to exist, and Alexandria becomes a part of the Byzantine Empire, whose capital was located in Constantinople (modern-day Turkey). Although the burning of the library, which this scene likely depicts, occurred in 640, the Byzantine Empire would continue for another 800 years, ultimately coming to an end in 1453 with the Ottoman sacking of the capital city. As a result, the library’s destruction did not affect the stability of any empire, but rather caused the loss of great knowledge.

Continued in "A Historical Tour of Walt Disney World: Volume 2"!

About Theme Park Press

Theme Park Press is the world's leading independent publisher of books about the Disney company, its history, its films and animation, and its theme parks. We make the happiest books on earth!

Our catalog includes guidebooks, memoirs, fiction, popular history, scholarly works, family favorites, and many other titles written by Disney Legends, Disney animators and artists, Mouseketeers, Cast Members, historians, academics, executives, prominent bloggers, and talented first-time authors.

We love chatting about what we do: drop us a line, any time.

Theme Park Press Books

The Unauthorized Story of Walt Disney's Haunted Mansion The Ride Delegate 501 Ways to Make the Most of Your Walt Disney World Vacation The Cotton Candy Road Trip The Wonderful World of Customer Service at Disney Disney Destinies Disney Melodies The Happiest Workplace on Earth Storm over the Bay A Historical Tour of Walt Disney World: Volume 1 Mouse in Transition Mouseketeers Down Under Murder in the Magic Kingdom Walt Disney and the Promise of Progress City Service with Character Son of Faster Cheaper A Tale of Two Resorts I Saw Ariel Do a Keg Stand The Adventures of Young Walt Disney Death in the Tragic Kingdom Two Girls and a Mouse Tale Ears & Bubbles The Easy Guide 2015 Who's the Leader of the Club? Disney's Hollywood Studios Funny Animals Life in the Mouse House The Book of Mouse Disney's Grand Tour The Accidental Mouseketeer The Vault of Walt: Volume 1 The Vault of Walt: Volume 2 The Vault of Walt: Volume 3 Who's Afraid of the Song of the South? Amber Earns Her Ears Ema Earns Her Ears Sara Earns Her Ears Katie Earns Her Ears Brittany Earns Her Ears Walt's People: Volume 1 Walt's People: Volume 2 Walt's People: Volume 13 Walt's People: Volume 14 Walt's People: Volume 15

Write for Theme Park Press

We're always in the market for new authors with great ideas. Or great authors with new ideas. Whichever type of author you are, we'd be happy to discuss your book. Before you contact us, however, please make sure you can answer "yes" to these threshold questions:

Is It Right for Us?

We specialize in books that have some connection to Disney or theme parks. Disney, of course, has become a broad topic, and encompasses not just theme parks and films but comic books, animation, and a big chunk of pop culture. Your book should fit into one (or more) of those broad categories.

Is It Going to Make Money?

There's never a guarantee that any book will make money, but certain types of books are less likely to do so than others. They include: hardcovers, books with color photos, and books that go on forever ("forever" as in 400+ pages). We won't automatically turn down these types of books, but you'll have to be a really good salesman to convince us.

Are You Great to Work With?

Writing books and publishing books should be fun. The last thing you want, and the last thing we want, is a contentious relationship. We work with authors who share our philosophy of no drama and zero attitude, and the desire for a respectful, realistic, mutually beneficial partnership.

If you said "yes" three times, please step inside.