- Visit the Imagineering Graveyard

- Now Sailing: "Skipper Stories" - Tales from the Jungle Cruise

- Coming Soon: The biography of Disney animator Jack Hannah

- Coming Soon: A Haunted Mansion anthology

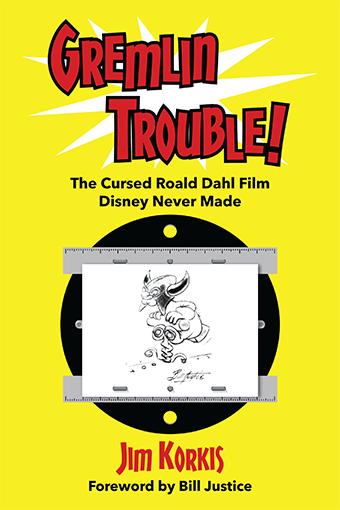

Gremlin Trouble!

The Cursed Roald Dahl Film Disney Never Made

by Jim Korkis | Release Date: February 25, 2017 | Availability: Print, Kindle

Blame It on Gremlins?

In the 1940s, Walt Disney had his hands on a new film franchise involving gremlins, little creatures that caused mischief, mostly of the mechanical kind. But no gremlins film was ever made. Walt himself cancelled the project. This is the story of what went wrong. (And it wasn't gremlins.)

Dashing RAF pilot Roald Dahl, best-known as the author of Willie Wonka and the Chocolate Factory, wrote his first book on a topic familiar to his fellow pilots: gremlins. These nasty buggers were often held responsible whenever a British plane was damaged or crashed during World War II.

Dahl convinced Walt Disney that a film, equal parts live action and animation, about gremlins, who were essentially Nazi saboteurs, would be a great companion to such Disney classics as Snow White, Fantasia, and Pinocchio.

Disney bought the rights—in fact, they still own the rights— to Dahl's gremlins, but then ran into a problem bigger than any mythic beast: Dahl himself.

As the Disney studio struggled to make heroes out of the malicious gremlins, and labored to write a script that would appeal to an American audience, a wave of "gremlin mania" swept the country, but Disney had no film to take advantage of it, due in large part to Dahl's lack of cooperation and outright opposition.

Americans soon tired of gremlins, and Disney soon tired of Dahl. The incomplete story, art, and animation for the proposed film was chucked deep into the Disney archives, where it remains today.

Best-selling author Jim Korkis presents the fascinating tale of Walt Disney and the gremlins, from Dahl's early involvement to a mini-resurgence in recent years, with the publication of a trio of gremlins graphic novels.

Table of Contents

Foreword

Introduction

Chapter 1: Walt Goes to War

Chapter 2: What Are Gremlins?

Chapter 3: Who Was Roald Dahl?

Chapter 4: Guide to Dahl’s Gremlins

Chapter 5: Disney’s Fifinella

Chapter 6: Disney Gets the Gremlins

Chapter 7: Bill Justice Interview

Chapter 8: The Cosmopolitan Story and Clause 12

Chapter 9: The Random House Book

Chapter 10: Gremlin Concerns

Chapter 11: Walt Disney Talks Gremlins

Chapter 12: Gremlin Merchandise

Chapter 13: The Life-Saver Controversy

Chapter 14: Gremlin Comic Books

Chapter 15: Gremlin Insignia

Chapter 16: The Animated Feature

Chapter 17: What Killed the Gremlins?

Chapter 18: The Warner Brothers Gremlins

Chapter 19: Disney's Failed Gremlins Revival

Chapter 20: The Dark Horse Gremlins Revival

Appendix A: The Disney Studio's War Cartoons 1942-1943

Appendix B: zisney Training Films 1942-1943

Selected Bibliography

Foreword

I always tell people that I was just a lucky fellow who was able to find a job he loved. For me, that job just happened to be working for a unique genius named Walt Disney. There was no one else ever like Walt Disney and there never will be.

I joined the Disney studio in 1937 and worked there for forty-two years as an animator on both the shorts and the features, special projects with my friends X. Atencio and T. Hee, and finally as an Imagineer programming audio-animatronics characters.

One of the projects I worked on that was never made was the story of the gremlins concocted by writer Roald Dahl during World War II. Walt gave me the chance to actually design some new Disney characters and a book was published in 1943 featuring my illustrations.

I worked long and hard on that animated feature but, for a number of reasons, Walt decided not to pursue the project, despite investing quite a bit of money in it that we really didn’t have at that time.

One of the few mementos that I have kept over the decades from my time at Disney is The Gremlins book. In my copy, Walt wrote in his distinctive cursive style: “To Bill Justice—With my thanks and appreciation for a swell job. Sincerely, Walt Disney.”

He was trying to tell me that it wasn’t my fault that the film got shelved and that he was happy with the work I had done. When I look at it today, it still brings tears to my eyes that he took the time to do something like that.

When Walt Disney World opened in 1971, my job was to program the audio-animatronics figures in several of the attractions.

Out of boredom, I sketched Disney characters on my programming console.

Among the familiar characters like Donald Duck and Chip’n’Dale, it seemed appropriate given the problems we often had to include a few gremlins. I had to always explain to people who they were and that they were Disney characters.

I am glad that my friend Jim Korkis is writing a book about them so that people will know who they are.

I’ve known Jim since he lived in California and attended those Mouse Club and National Fantasy Fan Club conventions where I talked to fans. When I visited Walt Disney World, Jim was often my “opening act” when I did shows at Give Kids the World. Jim would do comedy magic and make balloon animals to warm up the audience for me drawing Disney characters on a big easel.

Walt used to call “Stalky” Dahl the “chief greminologist” because he was the ultimate expert on the subject. I consider Jim a top greminologist as well. He has reminded me of so much that I had forgotten over the years as well as sharing information that I never knew.

It was great fun spending time with Jim at the Disney Institute where he is an animation instructor and talking about the “good old days” at Disney like the gremlins. I just hope gremlins don’t decide to mess with his book to keep their secrets secret!

Introduction

When Walt Disney passed away in December 1966, his office at the Disney studio in Burbank, California, was closed off exactly as he left it, except for some activity by his secretaries in the first year who needed material located there and later by the maintenance staff that went in occasionally to dust and vacuum. It remained untouched until it was re-opened in 1971 for Disney archivist Dave Smith to document the room before things were removed.

Dave made some unexpected discoveries, including the original illustrated story script for the cartoon Steamboat Willie (1928) in the bottom drawer of Walt’s desk. Another unexpected discovery was a plush doll in mint condition that Charlotte Clark had made in 1943 of the character of Gremlin Gus for an unmade Disney animation project. It had been in Walt’s office as reference for well over two decades and no one had paid any attention to it being there. When Dark Horse Publishing created a new series of Disney gremlin merchandise in 2006, it used the doll found in Walt’s office for its re-created Gremlin Gus plush doll.

Ever since I first heard about the Disney gremlins in an article entitled “Walt Disney and the Gremlins: An Unfinished Story” by my friend and former writing and business partner John Cawley in the magazine American Classic Screen (Spring 1980), I was fascinated. With that article began my decades of personal research into the seemingly cursed film beginning with quizzing John about all the material he uncovered but was unable to include in his article because of space limitations.

Over the years, I wrote several short articles about different aspects of the unmade film. In 1997, I interviewed Disney animator Bill Justice extensively about his participation in the film, since he was the one who worked closely with author Roald Dahl and came up with the final Disney designs for the characters. He had shared some stories in his own book, Justice for Disney, but I was able to prod some more information from his self-proclaimed failing memory.

I wrote a lengthy article showcasing some of this new research in 1997 for the never-published issue 11 of the Disney fanzine Persistence of Vision that was to be devoted to Disney during World War II.

I wrote an article over a decade ago that was over 10,000 words for the prestigious cartooning magazine Hogan’s Alley #15 entitled “The Trouble with Gremlins: The True Story of a Never-Made Disney Animated Classic.” For years, it remained the definitive article about the film.

Author and film historian Leonard Maltin used it as a reference for his introduction to the Dark Horse Publishing reprint of the 1943 Random House release of The Gremlins in 2006.

I connected with David Lesjak, an acknowledged authority on Disney during World War II, who shared with me information he had gathered during his own research into the topic.

Many people wanted a book about Disney’s gremlins, but no one wanted to write it or felt they didn’t have all the necessary information to write it. I decided to give it a try so that at least the material I had found could be used by others.

Gremlins remain an intriguing concept and certainly the Disney designs are loaded with appeal which is why people keep coming back to the idea of trying to revive the idea.

If you find any errors of any kind in this book, you must realize that I am completely blameless. It is the work of gremlins, and by reading their secrets in the following chapters you are now on their list as well.

Sorry about that. Be careful when you fly.

Jim Korkis

Jim Korkis is an internationally respected Disney historian who has written hundreds of articles about all things Disney for over three decades. He is also an award-winning teacher, a professional actor and magician, and the author of several books.

Korkis grew up in Glendale, California, right next to Burbank, the home of the Disney studios. As a teenager, Korkis got a chance to meet the Disney animators and Imagineers who lived nearby, and began writing about them for local newspapers.

In 1995, he relocated to Orlando, Florida, where he portrayed the character Prospector Pat in Frontierland at the Magic Kingdom, and Merlin the Magician for the Sword in the Stone ceremony in Fantasyland.

In 1996, Korkis became a full-time animation instructor at the Disney Institute teaching all of their animation classes, as well as those on animation history and improvisational acting techniques. As the Disney Institute re-organized, Jim joined Disney Adult Discoveries, the group that researched, wrote, and facilitated backstage tours and programs for Disney guests and Disneyana conventions.

Eventually, Korkis moved to Epcot as a Coordinator for the College and International Programs, and then as a Coordinator for the Epcot Disney Learning Center. He researched, wrote, and facilitated over two hundred different presentations on Disney history for Cast Members and for such Disney corporate clients as Feld Entertainment, Kodak, Blue Cross, Toys “R” Us, and Military Sales.

Korkis has also been the off-camera announcer for the syndicated television series Secrets of the Animal Kingdom; has written articles for several Disney publications, including Disney Adventures, Disney Files (DVC), Sketches, and Disney Insider; and has worked on many different special projects for the Disney Company.

In 2004, Disney awarded Jim Korkis its prestigious Partners in Excellence award.

A Chat with Jim Korkis

If you have a question for Jim Korkis that you would like to see answered here, please get in touch and let us know what's on your mind.

You began exceptionally early as a Disney historian. You were how old?

I was about 15 when I interviewed Jack Hannah with my little tape recorder and school notebook with questions printed neatly in ink. I learned to develop a very good memory because often when the tape recorder was running, people would freeze up. So, I sometimes turned off the tape recorder and just took notes which I later verified with the person. I always gave them a chance to review what they had said and make any changes. I lost a lot of great stories, although I still have them in my files for future generations, but gained a lot of trust.

How were able to hook up with these guys

I was very, very lucky. I was a kid, and it never occurred to me that when I saw their names in the end credits of the weekly Disney television show that I couldn't just find their names in the local phone book and call them up. Ninety percent of them were gracious, but there were about ten percent who thought it was a joke and that maybe one of their friends had put me up to phoning them.

It was like dominoes. Once I did one interview and the person was pleased, he put me in touch with others. After some of those interviews were published in my school paper and local newspapers, it gave me some greater credibility. Later, when they started to appear in magazines, I got even more opportunities.

How do you conduct your research?

JIM: You know, one of the proudest things for me about my books is that not a single factual error has been found.

To do my research, I start with all the interviews I've done over the past three decades, some of which are some available in the Walt's People series of books edited by Didier Ghezz. When necessary, I contact other Disney historians and authorities to fill in the gaps. And I have amassed a huge library of books, magazines, and documents.

When I moved from California to Florida, I brought with me over 20,000 pounds of Disney research material. The moving company that had just charged me a flat fee was shocked they had so severely underestimated the weight, and lost thousands of dollars. That was over fifteen years ago and the collection has only grown since that time.

About The Vault of Walt Series

You've been writing articles and columns about Disney for decades. Why all of a sudden start writing Vault of Walt books?

JIM: I was fortunate to grow up in the Los Angeles area at a time when I had access to some of Walt’s original animators and Imagineers. They shared with me some wonderful stories. I wrote articles about their for various magazines and “fanzines” of the time. All of those publications are long gone and often difficult to find today.

As more and more of Walt’s “original cast” pass away, I realized that their stories had not been properly documented, and that unless I did something, they would be lost. Everyone always told me I should write a book telling these tales and finally I decided to do it.

Walt's daughter Diane Disney Miller wrote the foreword to your first book. How did that come about?

JIM: She actually contacted me. Her son, Walter, loved the Disney history columns and articles I was writing and would send them to her. I was overwhelmed that she enjoyed them. She was appreciative that I tried to treat her dad fairly and not try to psycho-analyze why he did what he did.

She also liked that I revealed things she never knew about her father. As we talked and I told her I was doing the book, I asked if she would write the foreword. She agreed immediately and I had it within a week. She even invited me to go to the Disney Family Museum in San Francisco and give a presentation. She is an incredible woman.

What was Diane's favorite story in the book?

JIM: Obviously, the ones about her dad were a big hit. She especially liked the chapter about Walt and his feelings toward religion. She told me that it accurately reflected how she saw her dad act.

What's your favorite story in the book?

JIM: That’s like asking a parent to pick their favorite child. I tried to put in all the stories I loved because I figured this might be the only book about Disney I would ever write.

One chapter that I have grown to love even more since it was first published is the one about Walt’s love of miniatures. I recently found more information about that subject, and then on the trip to Disney Family Museum, I was able to spend hours examining some of Walt’s collection up close.

About Who's Afraid of the Song of the South?

Why did you decide to write a book about Song of the South?

JIM: I wanted to read a “Making of the Song of the South” book, but nobody else was ever going to write it. I wanted to know the history behind the production, why Walt made certain choices, and as many behind-the-scenes tidbits that could be told. I didn’t want to read a sociological thesis on racism.

Fortunately, over the years I had interviewed some of the people involved in the production, had seen the film multiple times, and had gathered material from pressbooks to newspaper articles to radio shows of the era.

There are a lot of misconceptions about Song of the South. I wanted to get the facts in print and let people make up their own minds.

Did you learn anything new when writing the book?

JIM: I thought I knew a lot after being actively involved in Disney history for over three decades, but writing this book showed me how little I really know.

For example, I learned that it was Clarence Nash, the voice of Donald Duck for decades, who did the whistling for Mr. Bluebird on Uncle Remus’ shoulder. I learned that Ward Kimball used to host meetings of UFO enthusiasts at his home. I learned that the Disney Company tried for years to make a John Carter of Mars feature. I learned that Walt himself tried to make a sequel to The Wizard of Oz. I learned that Disney operated a secret studio to make animated television commercials in the mid-1950s to raise money to build Disneyland. And so much more.

Even the most knowledgeable Disney fans will find new treasures of information on every page of this book.

What's the biggest takeaway from the book?

JIM: Walt Disney was not racist. That is one of those urban myths which popped up long after Walt died, and so he was unable to defend himself.

In my book, I make it clear that Walt had no racist intent at all in making Song of the South. He merely wanted to share the famous Uncle Remus stories that he enjoyed as a child, and he treated the black cast with respect and generosity.

Many people don't realize that the events in the film take place after the Civil War, during the Reconstruction. So many offensive Hollywood films made at the same time as Song of the South, even one with little Shirley Temple, depicted the Old South during the Civil War in an unrealistic manner. Walt's film got lumped in with them, and he was a visible target for a much larger crusade.

Books by Jim Korkis:

- The Vault of Walt: Volume 3 (2014)

- Animation Anecdotes: The Hidden History of Classic American Animation (2014)

- Who's the Leader of the Club? Walt Disney's Leadership Lessons (2014)

- The Book of Mouse: A Celebration of Walt Disney's Mickey Mouse (2013)

- Who's Afraid of the Song of the South? And Other Forbidden Disney Stories (2012)

- The Vault of Walt: Volume 2 (2013)

- The Vault of Walt: Volume 1 (2012)

With John Cawley:

- Animation Art: Buyer's Guide and Price Guide (1992)

- Cartoon Confidential (1991)

- How to Create Animation (1991)

- The Encyclopedia of Cartoon Superstars: From A to (Almost) Z (1990)

Walt Disney was impressed when he met Roald Dahl (whom he nicknamed "Stalky") for the first time, and for a while it seemed that a Disney film based on Dahl's gremlins was a shoe-in.

Within months of his arrival in Washington, Dahl had written his first book entitled at the time Gremlin Lore. As a serving officer he was required to submit for approval everything he wrote to the British Information Services (BIS) based in New York.

He sent the rough draft manuscript to Sidney Bernstein at BIS. Before the war, Bernstein had been a British film entrepreneur who built many movie theater palaces and would later found Granada Television in England.

On July 1, 1942, Bernstein, sensing a project with fanciful similarities to Disney’s animated feature films, sent the draft to Walt Disney. He included a brief note that stated:

Flight Lieutenant Ronald [sic] Dahl has written a story about a New Dream Community that has risen in the Air Force, and I am enclosing you his effort which has been submitted through literary agent to a magazine.

The idea, I think, has great possibilities, as a film, if done in your own inimitable style. I have no personal interest in the matter, and if you would be interested in communicating with Dahl, his address is the British Embassy, Washington. I hope to be in Hollywood during August and have the pleasure of meeting you again.

By the beginning of 1942, the Disney studio was having both financial and creative challenges. The closure of the foreign market for American films and Walt’s agreement to make military and government training films “without profit” (only the cost of actual production) for the war effort resulted in a deficit of over a million dollars.

Money was going out but little if any was coming back in, and many of Walt’s most talented and dependable artists were serving in the armed forces or were in danger of being drafted soon.

After years of experimentation and artistic growth, Walt and his staff were now feeling constrained by the restrictions of limited animation, technical jargon, unrealistic deadlines, and interference by military advisors. Because of time, labor, and expense, more creative options such as the developing of a new animated feature had been shelved for the duration of the war, although a small handful of commercial entertainment animated shorts were still being made.

When Walt received the Gremlin Lore manuscript, he supposedly saw an opportunity to do a feature that would allow his staff to utilize the military expertise they had developed, maintain their commitment to the war effort, explore Walt’s recent fascination with the possibilities of aviation, and perhaps recapture some of the financial and creative rewards of Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937) with characters that had some superficial similarities to the dwarfs.

It would be a wartime fairy tale and seemed ideal for Disney’s animation expertise and talent. In addition, it would have the cache of being from a well-known decorated RAF pilot.

Walt immediately cabled both Dahl and Bernstein on July 13, 1942, to inform them of his interest. The telegram to Dahl stated:

Sidney Bernstein has sent me your story of the Gremlins. Believe it has possibilities. Would be interested in seeing your material and will have our Mr. Feitel in Washington contact you regarding same.

Chester D. Feitel was a sales representative for the Disney studio assisting marketing executive Kay Kamen with merchandising. He was based in Washington, D.C., and so geographically had easy access to Dahl.

That same day, Walt cabled Bernstein his thanks for locating the story:

Gremlins idea has great possibilities. Am contacting Dahl in Washington. Hope we will be able to work out something so we can produce it. Many thanks for sending it on to me. Looking forward to seeing you in Hollywood in August. Kindest regards, Walt Disney.

Three days later, Feitel’s written report of his meeting with Dahl was being read by Walt and Roy in Burbank, California:

Dahl is a young fellow…does not regard himself as a professional writer…. Gremlin Lore has not been copyrighted, and is not in the hands of any literary agent. The Gremlin characters are not creatures of his imagination as they are “well known” by the entire RAF and as far as I can determine no individual can claim credit.

Therefore, I doubt that the name “Gremlin” can be copyrighted.

Feitel added that the payment for the story would be shared by Dahl and the RAF, but that Dahl probably “would accept any reasonable deal on our usual basis.”

Two days later, on July 18, Kay Kamen wrote to Feitel:

Walt phoned and instructed me to see Dahl, obtain a copy of manuscript Gremlins and forward copy to you for conference with Roy.

Despite this fevered interest, it still took awhile to formalize the deal. Kamen’s note to Feitel dated August 3, 1942, states:

As per copy of letter to Roy which I sent to you, you will understand the present situation. Apparently Dahl’s contacts with Walt through Mrs. Mercier-Fairre [a Washington socialite that Dahl flirted with and who knew Walt casually] are interpreted by him as a proposition—one more liberal than my understanding of Walt’s and Roy’s wishes.

However, an arrangement was made with Dahl, and the Disney studio started devising ways to acquaint the American public with gremlins, develop a workable story with appropriate character designs, and establish a copyright for Disney’s version of gremlins just as it had for Disney’s versions of the foreign folk tales of Snow White and Pinocchio.

In an essay by Dahl entitled Lucky Break (1978), the writer remembered his first two-week excursion to the Disney studio in November 1942:

Because of the Gremlins, I was given three weeks’ leave from my duties at the Embassy in Washington and whisked out to Hollywood. There, I was put up at Disney’s expense in a luxurious Beverly Hills hotel and given a huge shiny car to drive about in.

Each day, I worked with the great Disney at his studios in Burbank, roughing out the story-line for the forthcoming film. I had a ball. I was still only twenty-six. I attended story conferences in Disney’s enormous office where every word spoken, every suggestion made, was taken down by a stenographer and typed out afterwards.

I mooched around the rooms where the gifted and obstreperous animators worked, the men who had already created Snow White, Dumbo, Bambi and other marvelous films, and in those days, so long as these crazy artists did their work, Disney didn’t care when they turned up at the studio or how they behaved. When my time was up, I went back to Washington and left them to it.

Dahl apparently made quite an impression when he was at the studio. By all accounts he played the role of the dashing, enthusiastic war hero and was very personable.

Walt threw a party in Dahl’s honor on his first night in Hollywood. Among those attending were actors Spencer Tracy (Walt’s polo buddy), William Powell, Dorothy Lamour, Greer Garson, and even Charlie Chaplin. One of the party games was having these distinguished screen stars act out different gremlins with Charlie Chaplin taking the prize for his interpretation of a Widget.

Dahl even hooked up with the first of many of his Hollywood affairs, an actress and socialite named Phyllis Brooks nicknamed “Brooksie,” who he treated so badly that she reportedly wanted to kill him just a few months after he had first succeeded in taking her to bed.

Walt was fond of nicknames and since Dahl was six-foot six-inches tall, Walt dubbed him “Stalky.” Walt also had trouble pronouncing the name “Roald” correctly, so this helped him alleviate that situation.

Continued in "Gremlin Trouble"!

How, indeed, do you create a warm family film about creatures that revel in damaging and downing British aircraft, and sending pilots to their doom? Even Walt was stumped, and Stalky was no help at all.

There is no one “smoking gun” for the death of the gremlins project. However, it is apparent that a combination of challenges contributed to its cancellation.

In his article “Walt Disney and The Gremlins: An Unfinished Story,” animation historian John Cawley wrote that as quickly as the public had embraced gremlins, they had now tired of them just as quickly:

By February [1943], it appeared that all the forces on Earth were fighting the completion of the film. Polls showed that filmgoers were tiring of war theme pictures. An Associated Press article titled “Gremlin Stuff is Getting Tiresome” echoed many media columnists when it stated that “They’ve been whimsied to pieces,” and that “very soon any member of the general public who ventures to wax coy about them will run the risk of getting his itsy-bitsy block stoved in.”

In March, an aviation magazine editor also complained about the constant attention to Gremlins. The problem was not so much the overabundance of material, but the image they gave the RAF: “Surely, the greatest flying and fighting service is not going to ape Sir James Barrie at his worst.”

By July, Walt told Dahl that instead of a feature, the Disney studio wanted to do the gremlins subject as a short cartoon and again expressed his concern over the infamous Clause 12 suggesting the British Air Ministry approval.

In a letter to Dahl dated July 2, Walt suggests:

Because of its timely nature and the fact that it should be out now, everybody thinks we ought to put it out as a short…. The complications that arise with the R.A.F. are other reasons why we do not want to consider the feature angle.

Every time I refer to Clause 12, I become a little apprehensive of what I may be facing. With the amount of money that is required to spend on a feature of this type, we cannot be subjected to the whims of certain people, including yourself. I do not mean this unkindly or in any sense as a criticism, but we feel it is simply not good business to undertake the production of the Gremlins as a feature at this time with so much risk involved.

I might fly to Canada to look things over and whatever information seems pertinent I can pass on to the boys. I believe they can get a lot out of films—when you get too authentic on the Gremlins, I feel it handicaps the subject for cartoon entertainment.

Dahl had planned so that Walt and some of his staff could visit the Royal Canadian Air Force headquarters to obtain material for the film. He had made arrangements for Walt’s crew to see Spitfires flying and an operational squadron of Hurricanes on the job with the pilots at readiness and in the dispersal huts in hopes of getting them all excited again about doing the feature. Walt never went.

A lengthy story conference on the project was held August 20, 1943, with Jim Bodrero, Ted Sears, Ham Luske, Wilfred Jackson, Dave Hand, Bill Berg, Dick Shaw, Bill Justice, Perce Pearce, Dick Kinney, and H.C. Holling in attendance trying to see if there was any way to go forward.

While Walt had already decided a month earlier that the material would be used to quickly produce a short, these men had put so much time and effort into the project that they decided to have one final meeting to see if there were any possibilities of still doing a feature.

Luske championed the approach of using live action combined with animation. He stated:

If you put [animated] fictitious pilots and fictitious Gremlins together, I don’t get any punch out of it.

Wilfred Jackson brought up the concern of trying to animate a realistic human figure, even if only the hands and feet were shown or just a silhouette from the back. Even the use of rotoscoping (shooting live action as a reference and then tracing over it, perhaps with some artistic exaggeration) had resulted in very stiff figures that did not move naturally.

Perce Pearce remarked at the meeting:

Basically if these little guys are the pilots’ alibis for their own stupidity, dereliction of duty, neglect, then you are taking some of the glamour off the RAF for me….

These Gremlins are very, very heavy villains to me…. They’re cute little guys that are nasty, and the crew doesn’t have a chance to pay them off. The fact that they’re representing the German bullets is enough to tell me that they are the spirit of the enemy.

Others agreed that any attempt to try to create some sympathy for the gremlin mayhem just resulted in trying to get audiences to accept and perhaps cheer for damage to Allied planes and pilots.

While the pilots may have had a certain concept of the gremlins and how they helped alleviate some of the stress of combat and other challenges, communicating that same feeling to an audience completely unfamiliar with the pilots’ culture was almost impossible.

Continued in "Gremlin Trouble"!

About Theme Park Press

Theme Park Press is the world's leading independent publisher of books about the Disney company, its history, its films and animation, and its theme parks. We make the happiest books on earth!

Our catalog includes guidebooks, memoirs, fiction, popular history, scholarly works, family favorites, and many other titles written by Disney Legends, Disney animators and artists, Mouseketeers, Cast Members, historians, academics, executives, prominent bloggers, and talented first-time authors.

We love chatting about what we do: drop us a line, any time.

Theme Park Press Books

The Unauthorized Story of Walt Disney's Haunted Mansion The Ride Delegate 501 Ways to Make the Most of Your Walt Disney World Vacation The Cotton Candy Road Trip The Wonderful World of Customer Service at Disney Disney Destinies Disney Melodies The Happiest Workplace on Earth Storm over the Bay A Historical Tour of Walt Disney World: Volume 1 Mouse in Transition Mouseketeers Down Under Murder in the Magic Kingdom Walt Disney and the Promise of Progress City Service with Character Son of Faster Cheaper A Tale of Two Resorts I Saw Ariel Do a Keg Stand The Adventures of Young Walt Disney Death in the Tragic Kingdom Two Girls and a Mouse Tale Ears & Bubbles The Easy Guide 2015 Who's the Leader of the Club? Disney's Hollywood Studios Funny Animals Life in the Mouse House The Book of Mouse Disney's Grand Tour The Accidental Mouseketeer The Vault of Walt: Volume 1 The Vault of Walt: Volume 2 The Vault of Walt: Volume 3 Who's Afraid of the Song of the South? Amber Earns Her Ears Ema Earns Her Ears Sara Earns Her Ears Katie Earns Her Ears Brittany Earns Her Ears Walt's People: Volume 1 Walt's People: Volume 2 Walt's People: Volume 13 Walt's People: Volume 14 Walt's People: Volume 15

Write for Theme Park Press

We're always in the market for new authors with great ideas. Or great authors with new ideas. Whichever type of author you are, we'd be happy to discuss your book. Before you contact us, however, please make sure you can answer "yes" to these threshold questions:

Is It Right for Us?

We specialize in books that have some connection to Disney or theme parks. Disney, of course, has become a broad topic, and encompasses not just theme parks and films but comic books, animation, and a big chunk of pop culture. Your book should fit into one (or more) of those broad categories.

Is It Going to Make Money?

There's never a guarantee that any book will make money, but certain types of books are less likely to do so than others. They include: hardcovers, books with color photos, and books that go on forever ("forever" as in 400+ pages). We won't automatically turn down these types of books, but you'll have to be a really good salesman to convince us.

Are You Great to Work With?

Writing books and publishing books should be fun. The last thing you want, and the last thing we want, is a contentious relationship. We work with authors who share our philosophy of no drama and zero attitude, and the desire for a respectful, realistic, mutually beneficial partnership.

If you said "yes" three times, please step inside.