- Visit the Imagineering Graveyard

- Now Sailing: "Skipper Stories" - Tales from the Jungle Cruise

- Coming Soon: The biography of Disney animator Jack Hannah

- Coming Soon: A Haunted Mansion anthology

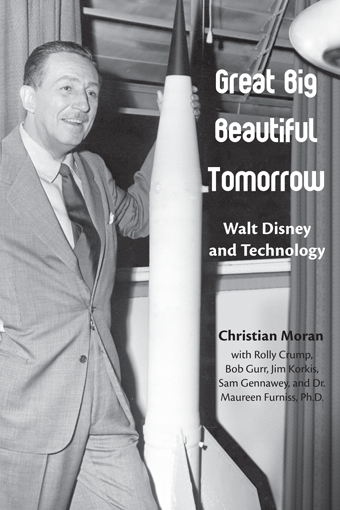

Great Big Beautiful Tomorrow

Walt Disney and Technology

by Christian Moran | Release Date: May 24, 2015 | Availability: Print, Kindle

Walt Disney and the Pursuit of Progress

Walt Disney is well-known for animation, theme parks, and Mickey Mouse. But his real passion was technology, and how he could use it to shape a better, prosperous, peaceful future for everyone.

From Walt's start in the 1920s as a struggling cartoonist to his unrealized dream of EPCOT, documentary filmmaker Christian Moran tells the amazing story of how technology created by Walt and the Disney Studio entertained and changed the world.

With lengthy recollections from Rolly Crump and Bob Gurr about their many years working for Walt, along with analyses from Disney historians Jim Korkis and Sam Gennawey, and animation historian Dr. Maureen Furniss, Ph.D., this book adaptation of Moran's forthcoming film, Great Big Beautiful Tomorrow, features:

- A new perspective on the life of Walt Disney, focusing on the technology he pioneered to make his magic happen

- How Walt used the Silly Symphonies as a "research and development" tool

- Walt's reluctance to build "Disneyland East", and why EPCOT was to be his crowning achievement

- Exclusive stories from Bob Gurr and Rolly Crump about Walt's robotics, Disneyland, Autopia, the 1964 World's Fair, and much more

Find out how Walt Disney shaped the future while entertaining the masses, and then catch the film when it's released in 2015.

Table of Contents

Introduction

Part One: Evolving Animation Through Technology

Chapter 1: Big Things Have Small Beginnings

Chapter 2: It All Started with a Mouse

Chapter 3: Silly Symphonies: Animation R&D

Chapter 4: The Struggle: Giving Birth to Feature Animation

Chapter 5: The Burbank Studio: Walt’s Animation Utopia

Chapter 6: ‘Pinocchio’: Masterpiece of Special Effects Animation

Chapter 7: ‘Fantasia’: The Art of Sight and Sound

Chapter 8: The Last Studio to Strike

Part Two: War and Recovery

Chapter 9: Walt and the War

Chapter 10: The Film That Won the War: ‘Victory Through Air Power’

Chapter 11: The Long, Hard Road

Chapter 12: ‘Cinderella’: Savior of the Disney Studio

Chapter 13: Subs & Squids: Adventures in Live-Action Filmmaking

Part Three: Expansion of the Kingdom

Chapter 14: The Journey to Disneyland

Chapter 15: Television: The New Frontier

Chapter 16: The Happiest Place on Earth

Chapter 17: Black Sunday

Chapter 18: Tomorrowland: Science-Factual Entertainment

Chapter 19: ‘Walt Disney’s Wonderful World of Color’

Chapter 20: Monorail: The Transportation System of the Future

Chapter 21: Walt Disney: Robotics Pioneer

Part Four: The Dream of Tomorrow

Chapter 22: The 1964 World’s Fair: Prelude to Utopia

Chapter 23: EPCOT: Designing Utopia

Chapter 24: EPCOT: Walt’s Final Dream

Part Five: Walt's Death and Aftermath

Chapter 25: Shuffling Off This Mortal Coil

Chapter 26: EPCOT: The Dream Passes with Walt

Chapter 27: Disney After Walt

Conclusion

Selected Bibliography

Introduction

The name Walt Disney means different things to different people. To some it conjures up images of princesses and fairy tales. To others, a multi-billion-dollar media conglomerate. When I think of Walt, I think of positivity, progress, and the belief that tomorrow can always be better than today, if we simply work hard enough to make it so. In the nearly half century since his death, many myths and legends have sprung up about the man, not all of them kind or true. Some young people today don’t even realize that he was a real person, equating him to Ronald McDonald or Betty Crocker, a kind of corporate symbol.

Many biographies and treatises have been written about Walt Disney, but this book will focus on a section of his personality that is often overlooked: his life as a futurist and his use of technology to better not only the industry of animation, but also robotics, transportation, and even urban planning. Walt spent his life attempting to make people happy. Though that goal started with cartoons, it evolved to the point that by the time of Walt’s death, he was well into the process of building EPCOT, a “utopian” city where all 20,000 residents would be employed and where nearly all transportation would be electronically powered mass transit.

Growing up in the midwestern United States in the early 20th century, Walt was raised with a strong sense of community. He was extremely interested in inventors like Thomas Edison and Henry Ford, and looked up to American icons like President Lincoln. He read Jules Verne and visited the cinema whenever possible, mesmerized by the magic of the silver screen.

Sam Gennawey:

If you look at a lot of the people whom Walt said that he admired, you find that he liked inventors, he liked gadget guys. He believed in technology. Everything that he did, especially when he got cornered, involved technology. I think one of his great skills was the ability to use technology, use story, and allow the technology to subside to the back and let the story come to the front. Because really, technology that works the best is technology you never notice. It’s there, it just functions. He was one of the first people, I think, that found a way of doing that, especially through the entertainment industry.

But I think he was just a geek, ultimately he was just a technical geek. He liked looking at technology, he was fascinated by it. One of the things I think Walt enjoyed about being a celebrity, as much as he liked being a celebrity, was it gave him access into corporate headquarters to look at things. I have some wonderful photographs of Walt Disney in Huntsville, Alabama, with a bunch of rocket scientists, and you just look at his face and he’s like a little boy. It’s great!

Walt was taught the value of hard work by his father, Elias, who had his son delivering newspapers at a young age. Later in his life, Walt would recall waking up in the early hours of the morning to deliver papers in near-blizzard conditions, using up all his energy to push through snow banks, sometimes even passing out in them, then hurrying off to a full day of school before heading back out to deliver the evening edition of the paper. Though his relationship with his father could be described as strained, Walt had a strong love of family and was close to his siblings, particularly his brother and partner, Roy, and his sister, Ruth, whom he kept in contact with through letters until the last year of his life. After they had achieved success, Walt and Roy took care of their parents, putting them up in a house near the Disney Studio. I mention these things—family, hard work, and community—because they shaped Walt’s belief of what technology should be used for: to help people live happier, more productive lives, and to create the kind of society where it’s possible for them to do so.

Rolly Crump:

Well, he always looked ahead. I think one thing was—and this really is interesting, because it’s all based on family—that whatever we were going to do it, should be “family” [oriented]. I think he wanted a better life for families, and I think a lot of the things, especially with EPCOT [, were based around family]. EPCOT was based on a city of the future, and everything they did in there was futuristic, but it was also family-oriented. The projects that they had there—he wanted all the top industry, like Ford, General Electric, and all of the big companies, to have research structures in the complex so that the people who lived there could work for those companies. He really believed in cross-pollination. He didn’t like the idea that General Electric was doing this and somebody else was doing that, and they’re not working together. Because everything we did was teamwork, and he felt that the country should be run with teamwork.

Walt’s close friend Ray Bradbury described him as an “optimal behaviorist” because Walt would work to the best of his ability every day on the task at hand. That way, when he looked back at the end of the day, week, month, or year, he could reflect on what he had accomplished and know that he had achieved all that he was capable of. As Walt put it: “Why worry?, If you’ve done the very best you can, worrying won’t make it any better.”

What kind of a man was Walt Disney? Since his death he has been labeled a racist, sexist, anti-Semite, and an icon of mid-century American conservatism and capitalism. Any person who investigates any of these claims will find them to be untrue. In an interview conducted by Arn Saba in 1979, Disney cartoonist Floyd Gottfredson expressed his belief that many of these derogatory claims stem from Richard Schickel’s 1968 book, The Disney Version. Gottfredson said:

Most of the derogatory stories you heard were sour grapes stories, people who didn’t make it, and Walt gave them every chance in the world. He tried them over and over and shifted them around and so on. When they finally couldn’t make it and he had to let them go, that’s where these stories came from on the outside.”

In fact, Walt rarely fired anyone. He would move them to a dead-end area of the company in hopes that they would eventually quit.

So what proof do we have that these allegations are false?

Sexism. In the early days of animation, women were mostly confined to the Ink and Paint Department, not only at Disney, but at all animation studios. As Disney historian Jim Korkis writes in his Vault of Walt series of books, the allegations of sexism usually arise due to a standard form letter that was circulated in-house in 1938. The letter states that men starting at the Studio were to begin as in-betweeners in animation, and women were to begin in ink and paint. However, Korkis points out that more women worked outside of ink and paint by percentage at Disney than at any other animation studio of the time. In fact, animator Retta Scott joined the Story Department in 1938 and became an animator in 1941, well before women were animating at any other studio. Walt’s personal favorite artist was Mary Blair, a concept artist who would go on to do design work for Cinderella, Alice in Wonderland, Peter Pan, and the “it’s a small world” attraction. Retta Davidson became an effects animator in 1939, and nine other women became in-betweeners and background artists in 1941. This would never have happened at other studios. The women that worked at the Studio loved Walt, and he made sure that the male staff treated them with respect and dignity. An in-house memo was sent to all the men at the Studio in 1939 stating that crass language had been used by men around the women, and that Walt hoped the Studio would be a place where women could be employed without embarrassment or humiliation.

Anti-Semitism. In 1944, Walt joined a group known as the Motion Picture Alliance for the Preservation of American Ideals. Other members included Gary Cooper, Clark Gable, Ronald Reagan, Ginger Rogers, and John Wayne. The group claimed to be fighting against communist and fascist influences in Hollywood, and it has since been claimed that the organization held some anti-Semitic views. That is the beginning and the end of the allegations against Walt—that he was a member of an organization that expressed some anti-Semitic views. But if this makes Walt an anti-Semite, then why not Clark Gable and future president Ronald Reagan as well? In truth, Walt worked with, and was friends with, many Jewish people, such as his merchandising guru Kay Kamen, Disney executive Marty Sklar, and songwriters Richard and Robert Sherman. Walt’s daughter, Sharon, even dated a Jewish boy for a time, with no complaint from Walt. In 1955, the Beverly Hills chapter of B’nai B’rith named Walt their man of the year. Along with representatives of various Christian faiths, Rabbi Edgar Magnin took part in the opening ceremony for Disneyland.

Racism. Floyd Norman became the first black animator at Disney when he was hired in 1956. He was later moved by Walt to the Story Department, a very high honor indeed, for The Jungle Book. Norman claims to have never witnessed or heard claims from others at the Studio that Walt ever did or said anything racist. Even during production of Song of the South, Walt attempted to bring in representatives from the NAACP to help ensure the film would not be offensive to black people. They declined his invitation. At most, one might claim that Walt allowed racially insensitive material into some early productions, just as all the other studios did at the time. But, in terms of how he treated people, he was not a racist. Walt loved people of all races, religions, cultures, and genders. He even helped an employee who had been arrested on charges of engaging in homosexual behavior. That employee stayed on at Disney for years.

Jim Korkis:

There’s been talk that Walt didn’t care for women. Well, during the time period when Walt lived, women were considered second-class citizens. The only reason they had a job was to find a husband. Walt saw beyond that. In fact, in the 1940s, when other studios were only offering women the opportunity to do ink and paint (which is a very tough job to do, it’s very, very precise, and the women who did that did not feel demeaned by doing it, they took that as an art work), Walt had women who were animators, who were concept artists, who were story artists. He had women in positions of authority.

At a time when Jews were given a very hard time, Walt put them in positions of authority. At one point Kay Kamen said, “There’s more Jews working at the Disney Studio than in any of the books of the bible.”

Walt didn’t care about the color of your skin or your religion or your sex. Could you do the job? My friend Floyd Norman was one of the very first black animators. He was hired at the Studio by Walt himself when Floyd was just a teenager. In fact, afterwards Walt hired a second black animator, Frank Braxton. People don’t hear about that. I asked Floyd: “Did you see any difference in the way Walt treated you?” Floyd said, “That was the amazing thing. Walt made me an animator, which I wouldn’t have been able to get at any other studio. Then he promoted me to story man on Jungle Book, which in terms of status at the Disney Studio was very prestigious. Walt treated me just the way he treated everybody else; that none of us knew anything and he was going to make us do the best we could possibly do, more than we thought we could ever do.”

All of this is not to say that Walt was a perfect man. He had an ego and, sometimes, a temper. He demanded excellence from all of his employees, just as he demanded it of himself. He hired the absolute best, and he expected you to perform. He would never, but on rare occasion, compliment you to your face. He would compliment your work to others and expect them to tell you what he had said. He did not like being told “no”, while at the same time he despised yes-men. In his interview with Arn Saba, Floyd Gottfredson recounted that when Walt was working with a group at Imagineering on the new animatronics technology, someone said that what Walt wanted to do could not be done. Walt responded, “God damn it, if you can visualize it, if you can dream it, then there’s some way to do it! Now keep after it until we get it!” Those that understood the way Walt worked went on to thrive in the Walt Disney Company.

Jack Cutting began working at the Disney Studio in 1929, shortly after the initial success of Mickey Mouse. In a 1972 interview, he painted a very interesting picture of working with and being around Walt:

Walt was the catalyst that made it all work. He had tremendous ability to generate inspiration and he created an atmosphere in the Studio that gave direction to many of the artists who otherwise might have floundered on their own and not gone far, because they lacked Walt’s verve and bold concepts. Most talents need outside inspiration, and Walt supplied lots of it because his innate taste and creative perception was so far above average.

Walt was only 28 when I came to the Studio, but he seemed older and at times very serious-minded. I always felt his personality was a bit like a drop of mercury rolling around on a slab of marble, because he changed moods so quickly. I believe it was because he was extremely sensitive.

Walt had the instincts of an internationalist. He was fascinated by places and people who had been brought up in an environment that was different from the one he had grown up in. Although Walt could exude great charm if he was in the mood, he could also be dour and indifferent toward people. But this was usually because he was preoccupied by problems. Sometimes you would pass him in the hall, say hello, and he would not even notice you. The next time he might greet you warmly and start talking about a new project he was excited about. You might not understand at first what he was getting at because he didn’t always give you a preamble on the subject. If you didn’t pick up his chain of thought quickly, he would sometimes look at you as though you were slow-witted, because when he was excited about an idea it was clear to him and he assumed it was to everyone else.

The people who worked best with Walt were those who were stimulated by his enthusiasm for a story idea or whatever his subject was, and were able to build on his ideas and enthusiasm. More than once when he was in a creative mood and ideas were popping out like skyrockets, I have seen him suddenly look like he had been hit in the face with a bucket of cold water: the eyebrow would go up and suddenly reality was the mood in the room. This change of mood was often prompted by someone in the group being out of tune with the creative spirit that he was generating. Then he would say that he found it difficult to work with so-and-so. But Walt was also a realist and also practical and would pull the balloons down if he had second thoughts about something he had been very high on the day before.

Bob Gurr:

Walt had the niftiest working relationship with people because, unlike what business is today, where everybody has an MBA and you have layers of management with a president at the top and rungs of upper, middle, and lower management beneath him, right down to the operator level, Walt talked directly with anybody doing anything. He cut through all the layers of management.

In hindsight it’s very simple. Let’s say Walt gave an order down through a couple of layers. Well, that’s going to go through a filter, an agenda, before it reaches the bottom. And when that answer comes back up, it’s going to go through another filter with somebody’s agenda, and Walt might learn about something two weeks late and it’s wrong. Well, he’s two weeks late trying to fix it. Guess what? Just get out of the office, go walk around, and see what’s going on with your own eyes and talk to people.

So Walt was a classic Walk Around. This served a terrific purpose in two different ways. If something wasn’t quite right as things were progressing, Walt would be the first guy to see it. Well, guess what? He’s right there with the guy doing it and he can get into a conversation about it. But he would never threaten you and say, “You’re not doing what I told you to do!” Or, “We’ll fire you if you do anything wrong!” He would look at something and say, “Say, Bobby, what do you think if...”, and he’d suggest a little change. Now you understand that he’s interested in what you’re doing.

That led to a very interesting way of working, and let’s say you have a suggestion and he pursues it and it doesn’t work. Now you’d be terrified. Walt would just say, “Oh, well, we know what doesn’t work. We’ll just find another way and we’ll do that.” To your great relief,he didn’t fire you when your dumb idea bombed out, when you wasted his time and money. That was the most tremendous management style I have ever seen.

Rolly Crump:

On a personal level he was gorgeous, because whenever he talked to you he was always talking about whatever you were interested in. So he always put that in there, and he wasn’t dictatorial, he was just wanting to know what you were like as a person. He also got to know his guys. Everybody that he worked with, he knew them inside out and backwards. He was the best casting director that was ever put on this planet. He knew exactly who to put on what, which was just great.

So, the personal level was, whenever he came into the Model Shop he’d go to every table, talk to everybody there no matter who they were. He’d stop and talk to me about what I’m doing, and he was like a big sponge. I learned that from him. I learned to be a good sponge, and I think that’s a secret you need to pass on to other designers or people that are in art. Be a sponge and absorb as much as you can.

Walt looked at everybody as his team, and he knew that cross-pollination was what it would take to make that work. In fact, when he was in animation and he would work on a storyboard or a story for a film, he’d put two story men together that didn’t get along. He did that on purpose because he wanted them to kind of battle for what they felt was the best. He really understood how to work as a team and how to put people together.

Walt was a visionary, a man who believed not only that he and his team could build whatever he dreamed up, but that the human race could build a better world for all peoples. His ethos is most concisely expressed as, “If you can dream it, you can do it.”

If you are not already aware of the information contained within this book, I believe you will be fascinated by everything Walt accomplished, or attempted to accomplish, in his lifetime. He believed that it was important to understand the past, so that we could make more informed decisions as to how to move into the future. He is quoted as saying, “Around here we don’t look backwards for very long. We keep moving forward, opening new doors and doing new things, because we’re curious, and curiosity keeps leading us down new paths.”

Christian Moran

Christian Moran is a filmmaker and writer who was born on March 29, 1985, in Columbus, Ohio. He completed one year at Ohio State University, majoring in archaeology, before moving to Los Angeles at the age of 19 to attend film school. His first documentary, Ayahuasca Diary, was completed in 2008, and his documentary web series, Everything Will Be Alright, premiered in 2014. Along with his writing and filmmaking he heads his family’s charitable organization, the Grant Town Foundation.

Christian’s admiration of Walt Disney began by visiting the Disney parks as a child, but has evolved into an immense appreciation of the man, his ideals, and vision.

Today, Christian lives in Los Angeles with his exceptionally talented wife, Christina, and their three pets: Calvin, Nyx, and Tini.

To learn more about Christian Moran, visit his website:

A Chat with Christian Moran

Coming soon...

Disney Legend Rolly Crump talks about Walt’s concerns over using real birds in the Tiki Room, and how the “robotic” birds really do respond to music.

Walt and his wife, Lillian, were always picking up antiques and other interesting trinkets on their travels around the world. On one such trip to New Orleans, Walt purchased a small, mechanical bird. Upon his return to the Studio, Walt tasked Roger Broggie, head of the Disney Machine Shop, with figuring out how it worked and improving upon it. Walt then had the idea of having WED build a Confucius-type Audio Animatronics character to talk to guests outside of a planned Chinese restaurant that was to be built at the park. When that idea was scrapped, Walt went back to the concept of the mechanical bird. After various discussions, the concept evolved into what became Walt Disney’s Enchanted Tiki Room, the first Audio Animatronics attraction ever built.

Rolly Crump:

Walt would have an idea, and he’d come and we’d have a work session with maybe four or five of us with the idea. Then the session would go to maybe another session, another session, and then little by little we were into a project. I think a good example of that was the Tiki Room. They had a restaurant on Main Street, I worked on the concept, then they decided to move the restaurant into the Tahitian Terrace area. The fellow that was in charge wanted to have John Hench do an illustration of what a Tiki restaurant might look like, because it was going to be in that area. So John did this beautiful rendering. It wasn’t any bigger than that [makes a small frame with his hands]. It was a picture of a restaurant with birds in cages and totem poles with Tikis. Walt came in and he took one look at it and he said, “John, you can’t have birds in cages in the restaurant.” John said, “Why not?”. Walt says, “They’ll poop in the food.” John said, “No, no, no, no. They’re not real birds, they’re stuffed birds.” Walt said, “Disney doesn’t stuff birds, John.” John said, “No, they look like stuffed birds, they’re little mechanical birds.” “Walt said, Ohhhh, they’re little mechanical birds”. There’s about six of us in the meeting and somebody else in the meeting said, “Yeah, well, you know, if they’re mechanical birds we could have them chirp.” Then one of the other guys said, “Well, maybe we’ll get them to chirp back and forth to each other.” So that’s kind of how that meeting went. Then Walt left and, it was interesting, he had total recall. He’d come back a week later and pick it up right where we left off. So then on we went, and, as I said, there were just four or five of us who were in charge of designing the Tiki Room.

The Enchanted Tiki Room, built in Adventureland, was originally supposed to be a restaurant. But since the technology was so radical for its time, the patrons would stay much longer than they normally would, simply to watch the performance again and again. The restaurant would have shared a kitchen with the Tahitian Terrace, which itself no longer exists. Featuring a cast of roughly one-hundred-fifty-six Audio Animatronics characters, including fifty-four orchids, seven birds of paradise, twenty-four masks, twelve Tiki gods, four totem poles, twelve toucans, nine forktail birds, eight macaws, six cockatoos, and twenty various other birds, the Tiki Room was an instant success. The songs the characters sing and move to, most famously the Sherman Brothers’ “The Tiki Tiki Tiki Room”, have become Disney classics. Created during the height of the “Tiki Craze”, the attraction was sponsored by United Airlines to promote their flights to Hawaii.

The various characters were animated by pneumatic actuators triggered by various tones. As the musical score plays in the room, reeds attached to the characters pick up the vibration which sends an electronic pulse to move the pneumatic valves present on the robot. The computer control room for the show was quite a sight to behold in 1963. Located underneath the floor of the Tiki Room, computer banks as tall as the height of the room operated the animatronics through magnetic data tapes. As Walt said in the Disneyland Tenth Anniversary Special:

You know, the same scientific equipment that guides rockets to the moon is used to make Jose and his little friends in the Tiki Room sing, talk, move, and practically think for themselves. I guess you could call him a creature of the Space Age.

Continued in "Great Big Beautiful Tomorrow"!

Architect Victor Gruen gives Walt the idea for EPCOT.

In 1959, Walt received an invitation to visit insurance magnate James MacArthur at his home in Palm Beach, Florida. MacArthur, who also had large investments in RCA and NBC, was one of the three richest people in the country and was interested in helping Walt create a second Disneyland. Walt, however, wasn’t interested in simply building a Disneyland clone. Walt explained that, while he understood that building another theme park was necessary, his main goal was to build a city near the park on the same land. MacArthur, believing wholeheartedly in Walt’s abilities and vision, presented him with a dream offer: four-hundred acres for the park and an additional twelve thousand acres for the city and surrounding area. Walt was ecstatic. He had his brother Roy begin drawing up contracts with MacArthur to move forward on the offer. Unfortunately, when Roy began to make changes here and there to the gentleman’s agreement between Walt and MacArthur, the latter pulled out, leaving Walt back at square one.

Never dissuaded by a deal that fell through, Walt pushed on as only he could. According to Sam Gennawey, Harrison “Buzz” Price recounted that around this time Walt dropped most of his work at Disneyland, outside of Audio-Animatronics, and became totally focused on building a city. But why? Walt, as we know, was concerned about families and the happiness of all people. He had, after all, spent his entire professional life making people happy, first through his films, then by creating Disneyland. By the 1960s, Walt could see the writing on the wall. The 1950s had seen the growth of the suburb, but it had also witnessed the degeneration of city life. Urban areas were becoming slums, and those who were not able to move out were often forced to live lives that Walt considered to be beneath the dignity of human beings. He hated seeing people in miserable living conditions, which contributed to the collapse of families and to the future detriment of children. He believed there had to be a way to solve this problem, a way to not only make life in the city better, but to make cities places where people and families could thrive and grow. Not only did he believe that this was possible, he believed that he was, perhaps, the only person who could prove it, and because of this it was his responsibility to do so.

Walt began to read as much as he could on the subject of urban planning and design. He felt that through proper planning and design, you could create a city unlike any other that had ever been built. He began to read books such as Ebenezer Howard’s Garden City and every magazine article he could find on the subject. Among the articles he read was one in Horizon magazine titled “Out of a City, Out of a Fair”, by architectural critic Ada Louise Huxtable. In it she described a proposal by architect Victor Gruen for Washington D.C.’s bid for the 1964 World’s Fair, which we know was awarded to New York City because of its access to greater resources and capital.

Gruen was most famous for creating the world’s first indoor shopping mall in 1956, and his proposal for a D.C.-based World’s Fair intrigued Walt. In Gruen’s opinion, the biggest problem with the various World’s Fair projects was that immense amounts of money were spent on infrastructure for a fair, then that infrastructure would be torn down after the fair was over. Gruen proposed that D.C. build a permanent infrastructure that would be converted into a model city after the fair had run its course. He designed a circular city surrounded by a giant parking lot. The city would be elevated onto a platform and all of the utilities and services would be housed underneath, away from the eyes of the public.

Sam Gennawey:

When Walt read this article he said, “There’s the solution. I’m going to build that. I love it, it’s like Disneyland. It’s circular, it’s got this circular pattern to it. I like the idea of putting all of the services underground. I like the way that it’s organized. I like that there’s a city center, a real center there and everything sort of spreads out. I like everything about this. I even like the fact that he ran the numbers to show how viable that the thing would be. That the thing would actually make money at the time, too.” He liked everything about that, and from that moment forward he thought, “I like Florida, because I’ve now had a chance to visit. I now know what this city could look like. I’m now going to build this city.”

Continued in "Great Big Beautiful Tomorrow"!

About Theme Park Press

Theme Park Press is the world's leading independent publisher of books about the Disney company, its history, its films and animation, and its theme parks. We make the happiest books on earth!

Our catalog includes guidebooks, memoirs, fiction, popular history, scholarly works, family favorites, and many other titles written by Disney Legends, Disney animators and artists, Mouseketeers, Cast Members, historians, academics, executives, prominent bloggers, and talented first-time authors.

We love chatting about what we do: drop us a line, any time.

Theme Park Press Books

The Unauthorized Story of Walt Disney's Haunted Mansion The Ride Delegate 501 Ways to Make the Most of Your Walt Disney World Vacation The Cotton Candy Road Trip The Wonderful World of Customer Service at Disney Disney Destinies Disney Melodies The Happiest Workplace on Earth Storm over the Bay A Historical Tour of Walt Disney World: Volume 1 Mouse in Transition Mouseketeers Down Under Murder in the Magic Kingdom Walt Disney and the Promise of Progress City Service with Character Son of Faster Cheaper A Tale of Two Resorts I Saw Ariel Do a Keg Stand The Adventures of Young Walt Disney Death in the Tragic Kingdom Two Girls and a Mouse Tale Ears & Bubbles The Easy Guide 2015 Who's the Leader of the Club? Disney's Hollywood Studios Funny Animals Life in the Mouse House The Book of Mouse Disney's Grand Tour The Accidental Mouseketeer The Vault of Walt: Volume 1 The Vault of Walt: Volume 2 The Vault of Walt: Volume 3 Who's Afraid of the Song of the South? Amber Earns Her Ears Ema Earns Her Ears Sara Earns Her Ears Katie Earns Her Ears Brittany Earns Her Ears Walt's People: Volume 1 Walt's People: Volume 2 Walt's People: Volume 13 Walt's People: Volume 14 Walt's People: Volume 15

Write for Theme Park Press

We're always in the market for new authors with great ideas. Or great authors with new ideas. Whichever type of author you are, we'd be happy to discuss your book. Before you contact us, however, please make sure you can answer "yes" to these threshold questions:

Is It Right for Us?

We specialize in books that have some connection to Disney or theme parks. Disney, of course, has become a broad topic, and encompasses not just theme parks and films but comic books, animation, and a big chunk of pop culture. Your book should fit into one (or more) of those broad categories.

Is It Going to Make Money?

There's never a guarantee that any book will make money, but certain types of books are less likely to do so than others. They include: hardcovers, books with color photos, and books that go on forever ("forever" as in 400+ pages). We won't automatically turn down these types of books, but you'll have to be a really good salesman to convince us.

Are You Great to Work With?

Writing books and publishing books should be fun. The last thing you want, and the last thing we want, is a contentious relationship. We work with authors who share our philosophy of no drama and zero attitude, and the desire for a respectful, realistic, mutually beneficial partnership.

If you said "yes" three times, please step inside.