- Visit the Imagineering Graveyard

- Now Sailing: "Skipper Stories" - Tales from the Jungle Cruise

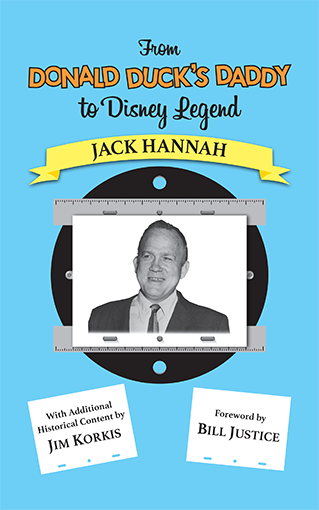

- Coming Soon: The biography of Disney animator Jack Hannah

- Coming Soon: A Haunted Mansion anthology

From Donald Duck’s Daddy to Disney Legend

by Jack Hannah (with Jim Korkis) | Release Date: January 12, 2017 | Availability: Print, Kindle

Donald Duck's Other Daddy

Disney animator, storyman, and director Jack Hannah's career with Walt (both Disney and Lantz) spanned decades, beginning with his first job at the Disney studio in 1933, as a clean-up artist. His stories are as memorable as the character he helped define, Donald Duck.

When Jack Hannah was hired by Disney, the Depression was in full swing. He was lucky to find the job. Walt put him to work as an animator, then as a storyman. But it was Hannah's years as a "Duck man", with Donald Duck cartoonist Carl Barks, that put him on the map. In all, he directed 65 Donald Duck shorts, and in his later years, directed Walt Disney himself for the live-action segments of Walt's Disneyland TV show.

Hannah's stories are simply told, often with a punch matching his brief stint as a Golden Gloves boxer, and focus on the artists, animators, storymen, and other creatives he encountered at the Disney studio, and later at the Walter Lantz Studio, where he created new characters as well as directing some of Lantz's originals, like Woody Woodpecker.

As a coda to his career, Hannah shares remembrances of the two most important "characters" in his life: Donald Duck and Walt Disney.

Plus, an exclusive, exhaustive filmography of Hannah's many shorts.

Table of Contents

Foreword

Introduction

Chapter 1: The Jack Hannah Story

Chapter 2: Hannah on Being a Disney Animator

Chapter 3: Hannah Animation Filmography

Chapter 4: Hannah on Being a Disney Storyman

Chapter 5: Hannah Story Filmography

Chapter 6: The Story Behind Pirate Gold

Chapter 7: Hannah Remembers Pirate Gold

Chapter 8: Working on Dell Comic Books (1942-1947)

Chapter 9: Hannah on Comics

Chapter 10: Hannah’s Comic Book Credits

Chapter 11: Hannah on Disney Directing

Chapter 12: Hannah Disney Directing Filmography

Chapter 13: Hannah Oscar-Nominated Cartoons

Chapter 14: Hannah on the Disneyland TV Show

Chapter 15: Hannah Disneyland TV Show Filmography

Chapter 16: The Walter Lantz Story

Chapter 17: Hannah on Lantz

Chapter 18: Hannah Lantz Filmography

Chapter 19: Hannah After Lantz

Chapter 20: The CalArts Story

Chapter 21: Hannah on CalArts

Chapter 22: Hannah Remembers Donald Duck

Chapter 23: Hannah Remembers Walt Disney

Chapter 24: Unmade Donald Duck Cartoons

Foreword

I will always be grateful to Jack Hannah.

Some people call me the father of Chip ‘n’ Dale. It is true that I have animated almost all of their scenes, except for the very earliest appearances where they looked much different.

It is not really accurate to think of me as their “father.” I think that accolade belongs to Jack Hannah. He directed all of their shorts and deserves much of the credit for their success.

In fact, he was responsible for their names. One of Jack’s assistants was Bea Selke who mentioned the Chippendale line of antique furniture and Jack was the one who realized it would be the perfect name for these feisty chipmunks.

I still don’t know why I was “cast” as the main animator for Chip ‘n’ Dale. One day, Jack simply handed me a batch of scenes for the cartoon Chip an’ Dale (1947). The characters became stars and more cartoons were developed and Jack kept giving me the chipmunk scenes to animate. I loved working on them even though they required more drawings than usual.

Jack and I worked well together and he always had great scenes for me to work on. I was part of his unit and one of the things that I remember is that he was always willing to listen to whatever ideas I had. He felt I had a good “story sense,” as he called it. He listened to everyone else on his team as well and I think that was one of the reasons he was such a great cartoon director.

He had experience in animating and doing story work and he brought those perspectives with him to his directing that made him different from anyone else I worked with. He knew how to communicate to an artist like Walt did because he was one.

Even though he was open to suggestions, he was a fighter and no push-over. He knew what he wanted. He always challenged me and others to put something “extra” into whatever I was doing. He really wanted me to bring out the personalities of Chip ‘n’ Dale and he never hesitated to push me to get it just right.

He once told me that we always need to do the best we can because we would have to live with all this stuff the rest of our lives. I didn’t realize at the time how right he was. Things I did almost half a century ago are up there on a huge screen for new audiences.

I always tried to do my very best work for Jack. When I became a director, I always thought back to working for Jack and how he did things and it helped me tremendously in how I did things and made decisions.

Every blank sheet of paper is a challenge. Every scene is a challenge. People ask, “Don’t you get bored sitting there drawing chipmunk after chipmunk?” I am trying to bring that chipmunk to life. That is the challenge of animation.

If you are thinking, “Oh, gosh, I got to make another drawing and then another drawing and another…,” then you are in the wrong business and you better get out because you don’t like to draw and that’s what this business is all about.

Walt Disney and the people I worked with at the studio like Jack really wrote the book on quality animation. I’d like to think I helped with a page here and there.

I was brought to tears when Jim Korkis told me that Jack held me in high esteem as well. Talking with Jim was like hearing Jack again as he told me the stories that Jack had told him. Jim knows and loves Disney animation. There’s no better person to tell Jack’s story.

I am happy he has decided to put together his interviews with Jack to share with a new generation. I don’t think people know about artists like Jack these days and their contributions. I am eagerly looking forward to reading all of this and reliving one of the best times of my life and learning some things I never knew.

Introduction

Jack Hannah was the first animator I ever met and the first animator I ever interviewed.

To this day, I have nothing but respect and fond memories of him and many of his Disney short cartoons still make me laugh out loud. He was always kind and patient and it was meeting him that led me to become a real Disney historian rather than just a Disney fan.

I was a teenager living in Glendale, California, and I was fascinated with animation. I would watch the weekly Disney television show and on the episodes that spotlighted animation, I would write down the names in the credits at the end of the show.

One of the first names I wrote down was “Jack Hannah” whose name appeared in several episodes devoted to animation. I found his address and phone number in the Glendale phone book.

I wrote a formal letter to “Mr. Hannah,” explaining my interest in animation and that I had many questions. I rewrote that letter several times before mailing it.

To my surprise, he wrote back within a few days “I would be most happy to meet with you on the early days of Donald Duck and my new affiliations with the Disney Studios. Please call me.” I did and we agreed to meet at his house on a Saturday afternoon.

It was August 1977.

Even though he lived in Glendale, he was a good fifteen minutes or more by car from where I lived, so my mother drove me and dropped me off. I was wearing the suit that I wore to church. It was solid black with a thin black tie on my starched white shirt. The temperature was in the high 80s. I wanted to look like someone who was mature and serious and not just a kid.

I had a rickety cassette tape recorder with a tiny attachable microphone. I also had several pens (because I feared they might run out of ink) and two spiral-bound school notebooks.

In one, I had written as much as I knew about Disney animation and some questions about Donald Duck. In those days, there really were not any easily obtainable source materials on animation or Disney history.

I had also arrived almost one hour early because I was fearful of being late and seeming rude. So, to kill time, I walked slowly around the block. That didn’t eat up enough time so I walked around the block again the other way, and then once more.

Finally, it was just ten minutes from the agreed-upon time so I hesitantly walked up the stone steps that were on an incline to the front door and ran the bell. A smiling older woman opened the door and I explained that I was Jim Korkis and that I had an appointment with Mr. Hannah.

She turned and yelled to the living room. “It is him! You were right!”

A cheerful Jack dressed in a sporty short-sleeve shirt came to meet me at the door. “We’ve been watching you from the front window for about an hour. We were wondering when you might come in.”

He ushered me into his living room. It was a pleasant, homey room, and he sat in an overstuffed chair by the front window. Near it was a small end table with a lamp and I set up my tape recorder and sat in a straight chair that was on the other side.

A smiling Mrs. Hannah left to do something in the kitchen.

I think we both expected that the interview might be a half hour or so. It lasted over three hours. I was lucky I brought several extra blank cassette tapes.

Fortunately, Jack was enthusiastic in talking about the good old days to an appreciative and awestruck teenager. It was as if the doors to wonderland had been opened wide to me as he rattled off unfamiliar names, interesting stories, and patiently explained some animation concepts.

The room only had one item that indicated Jack had ever worked at Disney. It sat proudly on the mantel above the fireplace: the famous bronze Duckster statuette that he had been given to Jack by Walt and Roy Disney for his years of exemplary service when he left the studio on May 27, 1959. The first Duckster was given out in 1952 to Martha Torge.

The Disney studio also gave out Mousecars (a Mickey Mouse Oscar statuette) to distinguished people at the studio. Walt gave the first Mousecar to Roy in 1947. The Disney company has no official record of how many Ducksters or Mousecars were handed out over the years.

The Duckster is a rarer award since fewer of them were given out, but it is known that ones were given to Carl Barks, Bob Karp, Al Taliaferro, and Clarence Nash, among others who were involved with Donald Duck. In 2005, Hannah’s family auctioned off his statuette for $4,813.

I later found out that Jack had sold off most of his Disney stuff. Los Angeles Dodgers’ baseball player Wes Parker got much of it. Parker specifically contacted Disney artists to purchase the material from them or their widows and offered a sizeable sum that would have been foolish to turn down.

The rest of the living room was decorated with photos of Jack’s family and some of his landscape paintings that had been exhibited in art galleries. “My wife won’t let me sell those,” he smiled. “I’m taking a break right now from another one I am working on. Usually I spend my Saturday in a room I converted into my art studio, but it is much too messy to hold a conversation there.”

Jack was 64 years old when I first interviewed him, which seemed ancient to me. He obviously embraced what he was doing at that time rather than nostalgically living in the past. In that first interview, his statement that “nobody seems old in this business” was never truer than applied to Hannah himself. He could easily have been mistaken for someone twenty years younger.

His eyes twinkled with mischief and an easy smile often came to light up his entire face as we talked. His voice was clear and deep. When it started to become a little raspy after three hours, I realized it was time to end the interview.

When he moved from his chair to illustrate the movements of some character, his body and face were as fluid and distinct as any character he ever directed.

He was short and stout and resembled a boxer, which may be one of the reasons he moved so easily. I later found out he had been in Golden Gloves tournaments when he was younger. “I didn’t like getting hit,” he smiled. “Doing art was safer, at least physically.”

He was filled with energy and was excited to be teaching character animation at California Institute of the Arts. He was not only passionate but articulate and I envied his students, one of whom he mentioned was a kid that he said showed a lot of promise, John Lasseter.

When we started the interview, Jack’s answers came slowly as he carefully worded his responses to make sure he stayed close to whatever the Disney studio might want to see in print. As the conversation continued and he began to trust my enthusiasm, he loosened up and was geniunely happy to relive the days at the studio, even regaling me with some off-color stories of studio parties.

Several times he asked that the tape recorder be turned off so he could gather his thoughts or to talk “off the record,” despite my assuring him that he could edit the final manuscript.

It took me several weeks to transcribe the interview and take it back to him and my heart dropped as he crossed out entire paragraphs. He had spent some time railing about Ben Sharpsteen being Walt’s “hatchet man” at the studio and how he was hated and Jack cut all of that out.

“It doesn’t add to the knowledge of animation to attack guys who can no longer defend themselves,” he told me as I pleaded with him to let me include some of the stories that he cut out. “Sometimes you get in a mood and days later you start thinking a little clearer. I think you’ve got enough stuff here.”

We did another interview over Christmas vacation that year to fill in some gaps and because his reading the transcript prompted some additional memories.

An edited version (for space) of that first interview appeared in the animation fanzine Mindrot #11 (July 1978) published by David Mruz. Jack even did a quick sketch of Donald painting a painting for me to include in the piece.

With Jack’s help I was even able to put together a filmography of his work at Disney. It was the first time he received published recognition for his animation work. A Florida art magazine had interviewed him previously over the phone and ran a short article on Jack and his paintings but had never sent him a copy.

This interview brought some much-deserved attention to Jack’s many accomplishments and the people at the Disney studio started contacting him for event appearances and projects.

I continued to interview him over the next decade, gathering material for articles that eventually appeared in Animania, Persistence of Vision, The Carl Barks Library, In Toon, Animato!, Walt’s People, and many other publications.

Jack used to joke that I was the official “Hannah Historian” and one night when he had to introduce Walter Lantz at some function, he frantically phoned me up and asked me to remind him of some of the stories he had shared about working at Lantz and what cartoons he had worked on there. I was happy to do so.

College, a girlfriend, and my interest in theater stole most of my time and I spent less and less of it with Jack, to my everlasting regret because he had so much more to share. My last interviews with him were done over the phone. He passed away from cancer in June 1994.

It amused but also irritated him that people confused him with Jack Hanna, the animal expert who regularly appeared on talk shows like Johnny Carson and David Letterman, and with animator and producer Bill Hanna of the famous television animation studio Hanna-Barbera.

“Don’t they see that I have an “h” at the end of my name?” he would laugh. “People send me mail all the time that should be going to these guys and I had to figure out how to forward it.”

While I was visiting him one day, Jack picked up the phone and talked with three other animators and told them they should let me interview them. One of them was Ward Kimball, the next animator I met in person. With a smile, Jack warned me to be careful because Ward was “crazy” and not to trust everything he told me.

What I remember about Jack was that he was feisty, funny, friendly, and an inspiration. His family was important to him. He loved getting together with friends from his days at the Disney studio and mourned the ones who had already died much too soon.

He was excited about his teaching work at CalArts and beamed with fatherly pride when he talked about his students. “When they go up to present their stuff, I’m just as nervous as they are,” he confided to me.

Even though Jack Kinney interviewed Jack several times when he was writing his book about his Disney days, he doesn’t mention Jack in the book. Jack told me that he had gone into great detail describing the push pin throwing contests at the studio, in which he apparently had some skill.

I gave Jack copies of books like Of Mice and Magic by Leonard Maltin where he was mentioned and other gifts to thank him for his patience and generosity.

When Jack passed away, I decided that I should write a book about him using the interviews we had done over the years. He deserved to be remembered. Even when he was alive, Jack never exploited his career as many of his peers did and was relatively unknown to most Disney and animation fans, so publishers weren’t interested in my project.

One told me that Jack was probably not that important since he wasn’t one of the fabled Nine Old Men, who at the time people thought were the best of the best and the only ones who really did the animation.

Moving to Florida to take care of my parents also slowed down the project. In the last five years I have built up a wonderful working relationship with publisher Bob McLain and his Theme Park Press that has enriched Disney history with its extensive catalog of books. Bob encouraged me to pull out my old original notes and put together a book about Jack Hannah.

While I had known Bill Justice since his many appearances in Los Angeles at Disney fan club conventions, I built up more of a friendship with him when I moved to Orlando. Bill and I would both perform at Give Kids the World. He would draw sketches of Disney characters and hand them out to the children and I did comedy magic and balloon animals.

He graciously agreed to write a foreword for my proposed Jack Hannah book. That foreword appears here now, after being filed away for almost twenty years.

There is material in this book that exists nowhere else, and over the years it has been annoying that some of the Jack Hannah quotes that have appeared elsewhere are from my interviews, often without credit. I wish others had taken the opportunity to interview Jack as well, getting material that I missed.

I have made corrections in Jack’s credit listings because he was often credited for things he never did or his credit was left off of other things that he worked on.

This is not a full biography but rather a scrapbook of memories. Try to imagine yourself on a warm August day sitting in a comfortable living room while a master storyteller takes a few moments for the first time to remember some of his old friends and the fun he had.

I enjoyed that feeling as I was putting together this material and looking at my scribbled notes in an old school notebook. I wish I had been smart enough to ask more questions.

Jack was not an angel. Walt often thought of him as a “problem child” because he could get so argumentative. In addition, like so many other Disney animators, he was sometimes too friendly with alcohol because of all the stress, but in his later years, removed from those studio pressures, he was very much in control.

Jack was full of life and good humor and no nonsense. I hope some of that comes across in the text. I miss him and will forever be grateful to him.

Jim Korkis

Jim Korkis is an internationally respected Disney historian who has written hundreds of articles about all things Disney for over three decades. He is also an award-winning teacher, a professional actor and magician, and the author of several books.

Korkis grew up in Glendale, California, right next to Burbank, the home of the Disney studios. As a teenager, Korkis got a chance to meet the Disney animators and Imagineers who lived nearby, and began writing about them for local newspapers.

In 1995, he relocated to Orlando, Florida, where he portrayed the character Prospector Pat in Frontierland at the Magic Kingdom, and Merlin the Magician for the Sword in the Stone ceremony in Fantasyland.

In 1996, Korkis became a full-time animation instructor at the Disney Institute teaching all of their animation classes, as well as those on animation history and improvisational acting techniques. As the Disney Institute re-organized, Jim joined Disney Adult Discoveries, the group that researched, wrote, and facilitated backstage tours and programs for Disney guests and Disneyana conventions.

Eventually, Korkis moved to Epcot as a Coordinator for the College and International Programs, and then as a Coordinator for the Epcot Disney Learning Center. He researched, wrote, and facilitated over two hundred different presentations on Disney history for Cast Members and for such Disney corporate clients as Feld Entertainment, Kodak, Blue Cross, Toys “R” Us, and Military Sales.

Korkis has also been the off-camera announcer for the syndicated television series Secrets of the Animal Kingdom; has written articles for several Disney publications, including Disney Adventures, Disney Files (DVC), Sketches, and Disney Insider; and has worked on many different special projects for the Disney Company.

In 2004, Disney awarded Jim Korkis its prestigious Partners in Excellence award.

A Chat with Jim Korkis

If you have a question for Jim Korkis that you would like to see answered here, please get in touch and let us know what's on your mind.

You began exceptionally early as a Disney historian. You were how old?

I was about 15 when I interviewed Jack Hannah with my little tape recorder and school notebook with questions printed neatly in ink. I learned to develop a very good memory because often when the tape recorder was running, people would freeze up. So, I sometimes turned off the tape recorder and just took notes which I later verified with the person. I always gave them a chance to review what they had said and make any changes. I lost a lot of great stories, although I still have them in my files for future generations, but gained a lot of trust.

How were able to hook up with these guys

I was very, very lucky. I was a kid, and it never occurred to me that when I saw their names in the end credits of the weekly Disney television show that I couldn't just find their names in the local phone book and call them up. Ninety percent of them were gracious, but there were about ten percent who thought it was a joke and that maybe one of their friends had put me up to phoning them.

It was like dominoes. Once I did one interview and the person was pleased, he put me in touch with others. After some of those interviews were published in my school paper and local newspapers, it gave me some greater credibility. Later, when they started to appear in magazines, I got even more opportunities.

How do you conduct your research?

JIM: You know, one of the proudest things for me about my books is that not a single factual error has been found.

To do my research, I start with all the interviews I've done over the past three decades, some of which are some available in the Walt's People series of books edited by Didier Ghezz. When necessary, I contact other Disney historians and authorities to fill in the gaps. And I have amassed a huge library of books, magazines, and documents.

When I moved from California to Florida, I brought with me over 20,000 pounds of Disney research material. The moving company that had just charged me a flat fee was shocked they had so severely underestimated the weight, and lost thousands of dollars. That was over fifteen years ago and the collection has only grown since that time.

About The Vault of Walt Series

You've been writing articles and columns about Disney for decades. Why all of a sudden start writing Vault of Walt books?

JIM: I was fortunate to grow up in the Los Angeles area at a time when I had access to some of Walt’s original animators and Imagineers. They shared with me some wonderful stories. I wrote articles about their for various magazines and “fanzines” of the time. All of those publications are long gone and often difficult to find today.

As more and more of Walt’s “original cast” pass away, I realized that their stories had not been properly documented, and that unless I did something, they would be lost. Everyone always told me I should write a book telling these tales and finally I decided to do it.

Walt's daughter Diane Disney Miller wrote the foreword to your first book. How did that come about?

JIM: She actually contacted me. Her son, Walter, loved the Disney history columns and articles I was writing and would send them to her. I was overwhelmed that she enjoyed them. She was appreciative that I tried to treat her dad fairly and not try to psycho-analyze why he did what he did.

She also liked that I revealed things she never knew about her father. As we talked and I told her I was doing the book, I asked if she would write the foreword. She agreed immediately and I had it within a week. She even invited me to go to the Disney Family Museum in San Francisco and give a presentation. She is an incredible woman.

What was Diane's favorite story in the book?

JIM: Obviously, the ones about her dad were a big hit. She especially liked the chapter about Walt and his feelings toward religion. She told me that it accurately reflected how she saw her dad act.

What's your favorite story in the book?

JIM: That’s like asking a parent to pick their favorite child. I tried to put in all the stories I loved because I figured this might be the only book about Disney I would ever write.

One chapter that I have grown to love even more since it was first published is the one about Walt’s love of miniatures. I recently found more information about that subject, and then on the trip to Disney Family Museum, I was able to spend hours examining some of Walt’s collection up close.

About Who's Afraid of the Song of the South?

Why did you decide to write a book about Song of the South?

JIM: I wanted to read a “Making of the Song of the South” book, but nobody else was ever going to write it. I wanted to know the history behind the production, why Walt made certain choices, and as many behind-the-scenes tidbits that could be told. I didn’t want to read a sociological thesis on racism.

Fortunately, over the years I had interviewed some of the people involved in the production, had seen the film multiple times, and had gathered material from pressbooks to newspaper articles to radio shows of the era.

There are a lot of misconceptions about Song of the South. I wanted to get the facts in print and let people make up their own minds.

Did you learn anything new when writing the book?

JIM: I thought I knew a lot after being actively involved in Disney history for over three decades, but writing this book showed me how little I really know.

For example, I learned that it was Clarence Nash, the voice of Donald Duck for decades, who did the whistling for Mr. Bluebird on Uncle Remus’ shoulder. I learned that Ward Kimball used to host meetings of UFO enthusiasts at his home. I learned that the Disney Company tried for years to make a John Carter of Mars feature. I learned that Walt himself tried to make a sequel to The Wizard of Oz. I learned that Disney operated a secret studio to make animated television commercials in the mid-1950s to raise money to build Disneyland. And so much more.

Even the most knowledgeable Disney fans will find new treasures of information on every page of this book.

What's the biggest takeaway from the book?

JIM: Walt Disney was not racist. That is one of those urban myths which popped up long after Walt died, and so he was unable to defend himself.

In my book, I make it clear that Walt had no racist intent at all in making Song of the South. He merely wanted to share the famous Uncle Remus stories that he enjoyed as a child, and he treated the black cast with respect and generosity.

Many people don't realize that the events in the film take place after the Civil War, during the Reconstruction. So many offensive Hollywood films made at the same time as Song of the South, even one with little Shirley Temple, depicted the Old South during the Civil War in an unrealistic manner. Walt's film got lumped in with them, and he was a visible target for a much larger crusade.

Books by Jim Korkis:

- The Vault of Walt: Volume 3 (2014)

- Animation Anecdotes: The Hidden History of Classic American Animation (2014)

- Who's the Leader of the Club? Walt Disney's Leadership Lessons (2014)

- The Book of Mouse: A Celebration of Walt Disney's Mickey Mouse (2013)

- Who's Afraid of the Song of the South? And Other Forbidden Disney Stories (2012)

- The Vault of Walt: Volume 2 (2013)

- The Vault of Walt: Volume 1 (2012)

With John Cawley:

- Animation Art: Buyer's Guide and Price Guide (1992)

- Cartoon Confidential (1991)

- How to Create Animation (1991)

- The Encyclopedia of Cartoon Superstars: From A to (Almost) Z (1990)

Jack has fond memories of his first boss, Walt Disney.

Everybody always wants to know, “What did you think about Walt?” You could say a lot about Walt just by the fact that everybody asks that question. He’s been gone awhile now and people still want to know about him. I could spend the whole afternoon talking about him and there would still be more to say.

Walt was one of the toughest men to work for. He always wanted more from you, but he never did it by encouraging you. There were times when you might have hated him or feared him, but you always respected him. Walt wasn’t doing it for himself. He was doing it for all of us in the business.

Walt had a great story mind. He knew what would entertain. He could look at any story and make it better. He really couldn’t draw well. He probably couldn’t even draw the Mouse’s tail, because he wanted that to have a personality. But he knew what was a good drawing, an effective drawing, to tell the story he wanted to tell. He was the driving force behind every damn thing there.

When you talk about Walt, you think about stories. Right before the war, Walt was making plans for the design of the studio. He had blocks on a table and he would keep moving them around and saying things like “the animation building should be here because of the light.” He was absorbed in doing all of this and somebody asked, “But, Walt, what about the war?” and he responded, “What war?” He could be completely focused on something and nothing else mattered.

Walt had this tremendous faith in the future of animation. Things he said about animation back in the 1930s, I still use in my teaching today.

You can’t ever deny that the man was a genius. There was no one else like him, ever. There was no doubt about it. If you were in his presence, you would know immediately what I am saying. There was an awe about him. You just felt it if he was in the same wing of a building you were in.

In the beginning, he got in with the group and was very gracious with the guys and their wives. That became a problem for him. You have to have that separation between the boss and those who worked for him. There would be these parties after work, and Walt would be there like one of the boys.

Some of the wives, after too many drinks, would come up and corner him and say, “Why isn’t my husband doing better? Why isn’t he being paid more?” Walt was always gracious with women. He respected women, but he couldn’t put up with this type of thing.

Finally, he stopped going to parties altogether, socializing altogether. But at the old parties, he was there having fun as just one of the guys.

One time I was doing a lot of woodworking at home. I was making a big “lazy susan,” but the piece of wood I was using was too big for my lathe, so on Saturdays I’d go down to work at the shop at the studio. Over the years, lots of guys did the same. We spent so much time at the studio that it was like a second home.

Walt would also come in on Saturdays to do work, sometimes working in the shop as well. I had a big sack of expensive cigars and left them on the bench while I went upstairs to use the big lathe. When I came back down, Walt was there working away, and I said, “I’ve got some really good cigars if you want one.” And he said, “Thanks, I’ve already helped myself.”

He’d gone over and taken one of my expensive cigars and already smoked it. If something was in the studio, he felt it belonged to him. I think that also applied to people. I could barely afford those cigars and I had gotten them as a special treat since my wife didn’t want me smoking them in the house.

I always got a kick out of that, him going over and taking it without asking. They were there and he wanted one. End of story. He’d be just one of the guys on a Saturday and then he’d turn right around on Monday morning and he could be so consumed with thinking about something that if I met him in a hall, maybe he would speak to me and maybe he wouldn’t.

When people ask me, “What would Walt think about this?” or “What would Walt do about that?” the thing is you never knew what he would do or say. He was always a surprise. You’d think, “This is something Walt will love,” and he would tear it to shreds while you stood there with your mouth open.

Continued in "From Donald Duck’s Daddy to Disney Legend"!

There were two Walts (that we know of) in Jack's life: Disney and Lantz. The latter, who usually went by Walter, hired Jack after the other Walt wouldn't give him what he really wanted: a live-action film to direct.

I had never met [Walter] Lantz before 1959, but he gave me a call and he and Bill Garity, Walter’s right-hand man at the time, took me to lunch at the Lakeside Country Club and invited me to join their studio.

Garity was another old-timer from Disney who had developed a multiplane camera and Fantasound, and he was now the vice-president and production manager, I believe, with Lantz.

We talked salary, but more importantly, Lantz made me an offer that I would be his supervising director. Walter wanted to do more traveling, so I would help run the production end of the studio from the creative side, and Garity would be running the business end, when Walter was on his vacation trips.

Walter told me that he was very short on stories and wanted me to bring my first story with me when I came over to start work. I got Milt Banta to assist me. Banta had worked with me on a couple of the Disney cartoons like Lambert the Sheepish Lion that had been nominated for an Oscar, and some of the Donalds.

Walter paid Milt’s writing fee. I brought Walter the story and he accepted it right away. I always thought it was very clever that from the moment I walked in as a director, I had my first story all ready to go. It was called Freeloading Feline.

When I left Disney, they were breaking up my whole unit. I took Riley Thompson with me, who was a very good draftsman. He had worked at Disney for years and did a little bit of everything: direction, animation, comic strips. I took Riley as my layout man when I went to Lantz’s.

I also took Ray Huffine and Al Coe, a good all-around animator. Coe did a lot of the Humphrey the Bear stuff for me. He worked out fine in my unit at Lantz’s. Even after I left Lantz, the people I brought over with me stayed on.

Walter once told me he was one of the luckiest producers in the business. He never had a training program or anything like that. He would just find people like myself who had a great deal of experience and catch ’em at just the right time when they were between studios.

He got Dick Lundy, a top director. Fred Moore came along and animated some beautiful stuff for Lantz. Fred was probably one of the most natural animators to ever hit the industry, and Lantz picked him up almost immediately after he left Disney.

Lantz got some of the top talent. I’ve seen cartoons from the Lantz studio done by these guys, and there are a couple of them that were great, top things, and done within budget. Lantz was really lucky, and he never hid the fact.

It was a completely different way of working at Lantz than at Disney. At the Disney studio, you had storymen, a layout man, a background man, and you had all these different departments. But at Lantz, the director practically did everything himself in the laying out of the picture for animation. You did a rough layout, anyway. Paul Smith worked that way. I changed that somewhat when I brought over Ray Huffine.

Lantz didn’t have hired storymen on staff. The directors usually had some background in story and had a lot of input into each cartoon. Walter would contract men from outside the studio to come in and do the stories. Then we’d have a meeting with these storymen telling the story and the director and Walter would sit in. Naturally, Walter would add little gags here and there. He was a pretty good gag man.

He was a gag man back in the old days when the philosophy of animation was “gag for gag’s sake” more than personality-type gags, which Disney was more interested in doing. As long as your animation was entertaining, Walter would overlook minor flaws in the story because of budget.

Right after I got started, Walter had to leave for Europe for a vacation trip or a business trip. I forget which. He asked me if I would be in charge of buying the stories and let Bill Garity know when I had okayed a story, so that the storymen could be paid.

Some of the storymen would get a bit ruffled when I would make ’em go back and make changes in the story before they got paid. Apparently, whoever was handling things before me let these guys get away with murder on some of these shorts, by accepting the first draft without corrections.

Anyway, some of these storymen would get a bit mad at me, because some of them were just knocking out the quickest story they could, so they could get paid. But now they had to go home and make corrections. When Walter got back from Europe, I had about nine to twelve stories all lined up, and he was tickled because he could go right into production without worrying about the story situation.

A few months after leaving Disney and working with Lantz, we all met at the Masquers Club at the testimonial-type dinner for artist Jimmy Swinnerton, a famous cartoonist and landscape painter. I was sitting with Lantz and Disney came over and made a remark, something to the effect of, “Is Jack breaking you, too, by going over budget?”

Walter immediately replied, “No, the first short just came in, and it was right on budget”. And Walt turned away and walked back to his table and that was the end of the conversation. I always got a kick out of that. I was very pleased and proud of Walter for standing up for me like that.

Walter was very supportive, especially when I was directing him in the live-action segments for his show. I think it made me more creative, because I didn’t have the fear of being rejected. So I came out with some ideas I felt were pretty good, and Walter went along with them.

I think there was a lot of good psychology there, because he wouldn’t squelch you right off the bat like Disney, but let you do some free thinking and come up with some new ideas.

Naturally, we could never use all of the ideas. Some had to be tossed out for one reason or another, like time or budget. Disney was a little tougher on you than that almost all of the time. You were afraid to go out in left field with Disney for fear of getting squelched in public.

Continued in "From Donald Duck’s Daddy to Disney Legend"!

About Theme Park Press

Theme Park Press is the world's leading independent publisher of books about the Disney company, its history, its films and animation, and its theme parks. We make the happiest books on earth!

Our catalog includes guidebooks, memoirs, fiction, popular history, scholarly works, family favorites, and many other titles written by Disney Legends, Disney animators and artists, Mouseketeers, Cast Members, historians, academics, executives, prominent bloggers, and talented first-time authors.

We love chatting about what we do: drop us a line, any time.

Theme Park Press Books

The Unauthorized Story of Walt Disney's Haunted Mansion The Ride Delegate 501 Ways to Make the Most of Your Walt Disney World Vacation The Cotton Candy Road Trip The Wonderful World of Customer Service at Disney Disney Destinies Disney Melodies The Happiest Workplace on Earth Storm over the Bay A Historical Tour of Walt Disney World: Volume 1 Mouse in Transition Mouseketeers Down Under Murder in the Magic Kingdom Walt Disney and the Promise of Progress City Service with Character Son of Faster Cheaper A Tale of Two Resorts I Saw Ariel Do a Keg Stand The Adventures of Young Walt Disney Death in the Tragic Kingdom Two Girls and a Mouse Tale Ears & Bubbles The Easy Guide 2015 Who's the Leader of the Club? Disney's Hollywood Studios Funny Animals Life in the Mouse House The Book of Mouse Disney's Grand Tour The Accidental Mouseketeer The Vault of Walt: Volume 1 The Vault of Walt: Volume 2 The Vault of Walt: Volume 3 Who's Afraid of the Song of the South? Amber Earns Her Ears Ema Earns Her Ears Sara Earns Her Ears Katie Earns Her Ears Brittany Earns Her Ears Walt's People: Volume 1 Walt's People: Volume 2 Walt's People: Volume 13 Walt's People: Volume 14 Walt's People: Volume 15

Write for Theme Park Press

We're always in the market for new authors with great ideas. Or great authors with new ideas. Whichever type of author you are, we'd be happy to discuss your book. Before you contact us, however, please make sure you can answer "yes" to these threshold questions:

Is It Right for Us?

We specialize in books that have some connection to Disney or theme parks. Disney, of course, has become a broad topic, and encompasses not just theme parks and films but comic books, animation, and a big chunk of pop culture. Your book should fit into one (or more) of those broad categories.

Is It Going to Make Money?

There's never a guarantee that any book will make money, but certain types of books are less likely to do so than others. They include: hardcovers, books with color photos, and books that go on forever ("forever" as in 400+ pages). We won't automatically turn down these types of books, but you'll have to be a really good salesman to convince us.

Are You Great to Work With?

Writing books and publishing books should be fun. The last thing you want, and the last thing we want, is a contentious relationship. We work with authors who share our philosophy of no drama and zero attitude, and the desire for a respectful, realistic, mutually beneficial partnership.

If you said "yes" three times, please step inside.