- Visit the Imagineering Graveyard

- Now Sailing: "Skipper Stories" - Tales from the Jungle Cruise

- Coming Soon: The biography of Disney animator Jack Hannah

- Coming Soon: A Haunted Mansion anthology

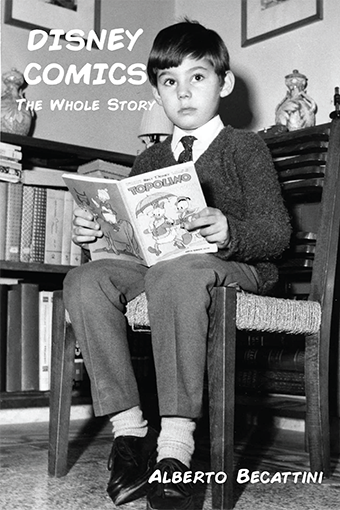

Disney Comics

The Whole Story

by Alberto Becattini | Release Date: August 15, 2016 | Availability: Print

An Encyclopedic Reference of Disney Comics

From the United States to Italy, from France and Spain to Brazil, Turkey, Russia, and beyond, noted comics historian Alberto Becattini traces the evolution of Disney comics around the world in the most authoritative, comprehensive treatment of the "Disney funnies" ever put into print.

Becattini chronicles not just the comics themselves but their creators, beginning with Floyd Gottfredson and Carl Barks and continuing through their countless disciples, including Romano Scarpa, Claude Marin, and Daniel Branca.

With its monumental index and thorough bibliography, Disney Comics is an indispensable tool for researchers and scholars, but also an epic, entertaining read for anyone who has thrilled to the adventures of Mickey, Donald, Goofy, and the hundreds of other Disney comics stars.

Table of Contents

Foreword

Introduction

Chapter 1: More Than Funny Animals: The Disney Newspaper Strips

Chapter 2: Four-Color Daydreams: The U.S. Disney Comic Books

Chapter 3: Custom-Made Mice and Ducks: The “Studio Program”

Chapter 4: God Save the Mouse: Disney in Britain

Chapter 5: Spaghetti Mice and Ducks: Disney Comics in Italy

Chapter 6: The French Connection

Chapter 7: El Ratón Mickey y El Plato Donald: Disney in Spain

Chapter 8: The Scandinavian Way

Chapter 9: The Disney Characters Around Europe—and the World

Chapter 10: High Quality from the Netherlands: Ducks and Mice from Holland

Chapter 11: South of the Border with Disney: Donald & Co. in Spanish-Speaking Latin America

Chapter 12: Blame It on the Samba: Donald Duck Meets José Carioca

Notes

Further Reading

Foreword

Ask an American kid if he knows where Mickey was born and you will hear “in the cinema or on TV.” Ask the same question to French or Italian children and they will undoubtedly answer: “in a comic book.”

You should not be surprised: most European kids learn to read thanks to Disney comics. And this is not a recent phenomenon: the first European Mickey Mouse magazine, Topolino, was launched in Italy in 1932. The French Journal de Mickey was born in 1934. Both are still widely read today. Nor is it only Western Europe that has a long Disney-comics history: the former Yugoslavia counted at least six Disney-related publications in the ’30s; Poland had its Mickey Mouse magazine in 1939; and on it goes.

In 1935, during their European “Grand Tour,” Walt and his brother Roy checked the plans for the upcoming Mickey Mouse Weekly which was about to be launched in the UK, straightened up a sketchy contract situation linked to the newly created Journal de Mickey, and signed a contract with publisher Mondadori to whom they transferred the Topolino license. Disney comics were big business already.

All of this would be limited to a fascinating footnote in the history of Disney publishing and merchandising, though, if it weren’t for the huge amount of Disney comics produced overseas since the 1930s. If you live in the United States you probably already know that many Disney characters were created by artist Carl Barks and born in the comics: Uncle Scrooge, Magica De Spell, Gyo Gearloose, and the Beagle Boys are all good examples. But what you probably do not realize is that many new Disney characters are the figment of the imagination of local Disney artists: Brigitta MacBridge, Scrooge McDuck’s self-appointed girlfriend; Gideon McDuck, a newspaper editor and Scrooge’s brother; and Trudy Van Tubb, Black Pete’s accomplice in crime, to name a few, were all invented by the Italian Romano Scarpa and are alive and well to this day. Superduck, Donald’s alter ego, was created by two other Italians: Guido Martina, and Giovan Battista Carpi. Jose Carioca’s nephews Zico and Zeca, and Jose’s friend Nestor, were invented by Brazilian comic artists. The list is almost endless.

None of this should be a surprise when one considers that, over the years, countries like Italy, Denmark, France, and Brazil have generated thousands of pages of local Disney comics. In fact, when I was a small kid, I first became interested in reading and thanks to a French Disney comic book series scripted by Pierre Fallot and drawn by Pierre Nicolas: Mickey à Travers les Siècles (“Mickey Through the Centuries”) which featured a time-traveling Mickey. No wonder I later became a Disney historian…

In other words, if Disney history is only understood as the history of American cartoons and theme parks, you are missing a large part of Disney’s creative history. Twenty years ago, I discovered Alberto Becattini’s newly released book Disney’s Comics, la Storia, i Personaggi: 1930–1995. I knew that I was finally going to be able to start understanding this fascinating creative history. The book was in Italian, however. I speak three other Latin languages and was therefore able to decipher most sections. Yet two big frustrations remained: I wanted to be able to read the book from cover to cover and I wanted to share my excitement with all of my fellow Disney historians. I knew this would only happen if the book were released in English. Twenty years later, thanks to Theme Park Press, this dream becomes a reality … with an added bonus since my good friend Alberto has updated his magnum opus.

Who could wait to start reading?

Introduction

The story behind this book is like the road in one of the most beautiful Beatles songs—long and winding. It was, in fact, in March 1987 that a British publisher asked me to write a book on the classic Disney comics, from 1930 until the 1960s. Of course I accepted with enthusiasm, although I knew from the start that the book would go beyond the limit set by the publisher, as it seemed silly to write a history of Disney comics which would have to stop almost thirty years before current events. So I threw myself headlong into research. At the Disney Archives in Burbank I found a lot of factual information and I got to leafing through pages and pages of publications I had never seen before. After over a year’s work, including revisions, cross-checkings with the Archives, phone calls, correspondence, etc., I had finished writing the book. Release was scheduled for the end of 1988, then delayed to early 1989, then—much to my chagrin, in early 1990 the British publisher went bankrupt and the book entered a long “limbo” from which it only came out in 1995, thanks to Editrice Comic Art, which finally decided to publish an updated Italian version of it.

In the meantime, I had seen bits of my original manuscript being used here and there, only occasionally mentioning the source. But I did not mind. And I was still determined to have the book published in English. In 2014, I offered it to Bob McLain of Theme Park Press, who responded enthusiastically. Yet twenty years had gone by since the Italian version had been published, and a whole lot of things had happened in the “huge Disney comics microcosm.” It took me several months to update the manuscript, while I also rewrote entire chapters and wrote additional ones. The title of the book, Disney Comics: The Whole Story, may be pretentious, but my aim has been to cover Disney comics history from 1930 (when the first Mickey Mouse daily strip appeared in U.S. papers) to date. This is, consequently, a massive book, and I advise you to read it a little at a time, savoring each of its extremely dense twelve chapters, which deal with the development of Disney comics in several countries of the world where a local production has been found to exist or to have existed.

As much as I love the Disney characters, about which I have written hundreds of articles and essays since the early 1970s, this book is first and foremost a homage to the men and women who have been creating wonderful stories with those characters, giving them a new life on paper, which has been often different and even more fascinating than that which they have had on screen. Willing to credit as many as possible of these creative geniuses, I have filled the book with information about them, sometimes leaving them speak about themselves and those they knew in bits of interviews I had with them. I guess that in some spots I have not been able to avoid the “phone directory effect,” yet I also guess that is the price one has to pay when encompassing 75 years of Disney comics history. However, I have tried to balance the purely technical data with anecdotes and critical appreciations. My main aim, however, has been to write (or rewrite) something that would last, which could suit the eager reader and the Disney scholar alike as a reference point for years to come. Just have the patience to read, and judge for yourselves if I have succeeded or not.

Alberto Becattini

Born in Florence, Italy, Alberto Becattini is a high school teacher of English who has been writing about comics, illustration, and animation for over forty years. He has been a contributor to Italian Disney publications since 1992, and has also written for Alter Ego, Comic Book Artist, Comic Book Marketplace, and Walt’s People, among others. An indexer for the Grand Comics Database and the I.N.D.U.C.K.S. project, he has written books about Milton Caniff, Giovan Battista Carpi, Floyd Gottfredson, Bob Lubbers, Alex Raymond, Romano Scarpa, Alex Toth, and Matt Baker.

Apart from Walt Disney himself, the most prominent figure at Mickey's family reunions would be Floyd Gottfredson, who was thrown the job of drawing Mickey's newspaper strip in 1930, not expecting it to last.

In April 1930, Win Smith left the studio after quarrelling with Walt Disney (who wanted him to take over the scripts as well), and was replaced by a talented 25–year-old inbetweener named Floyd Gottfredson. Hired by Walt as a “temporary replacement,” Gottfredson ended up working on the strip for nearly 46 years, giving the newspaper Mickey Mouse a personality of his own, markedly different from that of his screen persona. Gottfredson’s first strip appeared on May 5, 1930 (his 25th birthday) and two weeks later the artist from Utah was also writing it. Walt continued to supervise his work for a while, but then, apart from occasional comments, he had nothing more to do with the comic-strip production which bore his name. Gottfredson drew, inked, and lettered the first few weeks of strips, but soon realized he would need some help to meet the ever-tight deadlines. Thus, during his first year with Mickey some of his dialogues were rewritten by a Screen Gems story-man whose name remains unknown, whereas his pencils were inked by visiting editorial cartoonist Roy Nelson (1905–1956) as well as by studio artists Jack King (1895–1958) and Hardie Gramatky (1907–1979). (The latter left Disney in 1936 to become a famous children’s book author and a water colorist. In 1948 his Little Toot was turned into an animated section of the Melody Time Disney cartoon feature.)

Starting in a haunted house and ending in the Wild West, Mickey Mouse in Death Valley inaugurated the continuity formula. Thereafter, the Mickey Mouse strip alternated longer stories with one-day gags. Among the characters featured in the longer stories during 1930–31 were the mischievous Mr. Slicker (whose gang robbed eggs from the small farm owned by Minnie’s parents, Marcus Mouse and Mrs. Mouse), Kat Nipp (an addict of Nepeta Cataria), Creamo Catnera (a cat boxer whose name obviously parodied that of Italian boxing champion Primo Carnera), and Butch, a big-hearted bully who was Mickey’s first sidekick. For a time, readers could even write in to claim a free “snapshot” of Mickey with Butch, specially drawn by Gottfredson.

These early adventures were situated mainly in suburban environments—fenced backyards inhabited by domestic animals. (These animals were almost without exception non-reasoning beings, unlike Mickey and his pals, with their proto-humanity.) Outside the yard, the streets were crowded with fat pig-faced men, mustachioed lion-tamers, sailors, milkmen, and monkey-faced blacks. All of these (including the tastelessly depicted blacks) were typical of the funny pages of those times—and, indeed, had been for the previous couple of decades. The Disney strips were competing well with the opposition, but they had yet to become truly innovative.

It was not until 1932 that another full-length outdoor adventure appeared. This was The Great Orphanage Robbery (January 11–May 14, 1932), and it heralded a new tradition in Mickey’s character portrayal. Now he became a sort of man for all seasons, a character who could take on any role that required action. The Great Orphanage Robbery, which featured Pete and Sylvester Shyster, was partly inspired by the cartoon shorts Mickey’s Mellerdrammer (released March 18, 1933) and The Klondike Kid (released November 12, 1932).

In the color Sunday pages, though, Mickey usually retained his original, “everyday” persona. These weekly strips had been appearing since January 10, 1932, although the very first one of them might have been written and drawn several months before by animation story-man Earl Duvall (1898–1969), who was inking the Mickey dailies in late 1930 to early 1931. The evidence in favor of this contention is that the first Sunday page featured a rather rudimentary prototype of Mickey’s dog Pluto, a much more refined version of whom had appeared in the dailies as early as July 8, 1931.

Written and drawn by Floyd Gottfredson and inked by Al Taliaferro (1905–1969) from its second release onwards, the Sunday page was manifestly designed for younger readers—as were most of the other funnies in the Sunday newspapers of that time. It usually featured a string of gags, which were sometimes linked. For instance, from July 31 to August 28, 1932, Mickey and Pluto faced a nasty dogcatcher named Dan, who was in fact Peg-Leg Pete’s alter ego; from September 18 to November 6, 1932, Mickey was kept busy by two pesky little twins, Morty and Ferdie (or Ferdy), after their mother, Mrs. Fieldmouse, had temporarily entrusted them to him. Although the kids called the Mouse “Unca Mickey,” they did not seem to be actually related to him, but when they reappeared in another string of Mickey Mouse Sunday pages from March 31–May 26, 1935, the kinship had been taken for granted.

As Floyd Gottfredson was given co-writers, the Mickey Mouse Sunday pages started to feature continuity series. The first one was The Lair of Wolf Barker (January 29–June 18, 1933), which saw Mickey, Minnie, Clarabelle Cow, Horace Horsecollar, and Dippy Dawg (created by Charles Philippi for the animated shorts, Dippy had just recently made his comics debut on January 8, 1933, soon to become more widely known as Goofy) go out west to manage Minnie’s uncle Mortimer Mouse’s ranch while he was on a business trip in Australia. All in all, only a dozen full-length stories appeared in the weekly pages, among which The Robin Hood Adventure (April 26 to October 4, 1936) stood out, as it was the only Sunday sequence that Floyd Gottfredson plotted, partly inspired by the cartoon shorts Mickey’s Garden (released July 13, 1935) and The Worm Turns (released January 2, 1937). Written by Hubie Karp (1914–1953) and drawn by Bill Wright (1917–1984), The Professor’s Experiment (November 21, 1943–March 12, 1944) was Mickey’s last Sunday continuity.

From 1932, with Gottfredson in charge of not only the art but also Disney’s Comic Strip Department, the Mickey Mouse daily and weekly strips were written by various story-men from the Disney animation studio, although Gottfredson continued to plot all the daily continuities until June 1943. Iowa-born Webb Smith (1887–1951), who scripted many Mickey Mouse animated shorts during the early 1930s (and who is credited with the invention of the storyboard), wrote Blaggard Castle (November 12, 1932–February 10, 1933), a “horror” story in which Mickey and Horace Horsecollar were trapped in a dark castle by a trio of mad ape scientists—Prof. Ecks, Doublex, and Triplex (all modeled after actor Boris Karloff as the “dumb” butler Morgan in the 1932 The Old Dark House horror movie). The plot bore some resemblance to the January 1933 Disney short The Mad Doctor, which had Webb Smith among its writers. One scene—where Mickey had a close shave in an alligator pit—was sufficiently graphic that King Features came close to insisting that it be excised.

Blaggard Castle was apparently the first Disney strip to be inked by Ted Thwaites (1886–1940), an Englishman who had joined Disney in November 1932. Until his death in November 1940, he inked and lettered all the best of the daily Mickey Mouse strips as well as many of the Sunday pages. He was very popular around the studio but he was, by all accounts, extremely gullible, and was therefore the target of many a practical joke. One of the classics was perpetrated by story-man Hubie Karp. Karp, although he could not speak any foreign languages, was brilliant at imitating foreign accents. He connected a microphone in his office to the radio on Thwaites’ desk. Every day, Thwaites tuned in to the BBC to hear the news—especially once World War II had started. Karp’s practice was to pretend that he was broadcasting from London—“Hello, America, this is the BBC!”—and then to come out with spurious stories. Once he modulated from his crisp English tones to Germanic ones, announcing that he was the captain of a U-boat currently negotiating the Thames with the intention of bombing London. Thwaites rushed from his office screaming: “They’re bombing London!”

Continued in "Disney Comics"!

Some of the best Disney comics have been created by Italian story-men and artists little known to American fans. Of these talents, none stood higher than Romano Scarpo.

Ever since the days of Pedrocchi’s first attempts on Paperino there have been purists who have regarded the “Italian contribution” with considerable disfavor. Many of these were people who had relished the memorable Mickey Mouse continuities created by Ted Osborne and Floyd Gottfredson, and who found it hard to stomach this “new wave” of domestic stories. One such reader was Romano Scarpa, who as a boy (he was born on September 27, 1927) had often contributed to the Topolino letters column his intelligent observations concerning Gottfredson’s work—even though, like everyone else in those days, he did not know the artist’s name. Later Scarpa realized his great dream by becoming an animator. Animation remained his primary interest; between 1943 and 1953 it was his main occupation in his home town of Venice, where he even opened his own studio; and much later, in 1988, he was allowed to animate a 30–second sequence for DuckTales, although this was never used.

Yet he never stopped reading his beloved U.S. Mickey Mouse continuities, as reprinted in the digest-sized Topolino from 1949 onwards. When he was hired by Mondadori in 1953 to work on Topolino he had acquired a perfect grasp of Bill Walsh’s narrative style and Gottfredson’s graphic technique of scanning scenes, and he had developed these ideas in the light of his own experience as an animator. His very first Disney story, a 51-pager for Topolino called Biancaneve e Verde Fiamma (“Snow White and Green Flame”), written by Guido Martina (issues 78–80), astonished the editors at Mondadori and showed immediately his enormous and already mature talent.

In the following year, 1954, when he did art for one of Martina’s zaniest tales, Paperino 3–D (“3–D Donald Duck”), which appeared in issues 97–99 of Topolino, he drew the “Walt Disney” signature into the last panel, which otherwise showed Uncle Scrooge chasing Donald around the rings of Saturn. Indeed, over the next 15 years, until Scarpa’s name was finally made public, most readers assumed that the stories he illustrated had originated in the United States.

The misunderstanding was justified, as it has to be said that Scarpa himself did his very best to reinforce it. For example, his second Mickey Mouse story, written by Martina, which he drew in 1955 (Topolino issues 116–119), had a plot filled with cloak-and-dagger situations, very much in the mode of the U.S. newspaper Mickey Mouse tradition of the late 1940s and early 1950s.

This story was Topolino e il doppio segreto di Macchia Nera (“Mickey Mouse and the Phantom Blot’s Double Secret”) and starred, in addition to the sinister black-caped villain, Goofy, Eega Beeva (as Eta Beta), Chief O’Hara (as Commissario Basettoni), Mr. Casey (as Manetta), and even Alice in Wonderland’s Mad Hatter as a hat-shop owner.

It was a matter of destiny that, when in 1955 the newspaper continuities in the United States were terminated, thereby cutting off Topolino’s access to outside material, Scarpa should be there to pick up the mantle and carry on in the Disney tradition which he so much respected. Throughout his career he strove to keep any taint of “provincialism” out of his stories, seeking instead, almost monomaniacally, to reproduce what was to him the perfect expression of what a Disney comic story should be—in other words, a story in the original U.S. style, rather than one in the new-fangled Italian style.

His next Mickey Mouse story, Topolino e il mistero di Tapioco Sesto (“Mickey Mouse and the Mystery of Tapiocus VI”), which appeared in Topolino in 1956 (issues 142–143), was written and drawn in daily-strip form, just as if it were designed to appear in the U.S. newspapers. Later it was reframed by Scarpa himself with scissors and glue in order to fit Topolino’s six-panel-per-page format.

Scarpa asked for and received permission to reproduce his “Walt Disney” signature every now and then in these pages, and on occasion he included in the background a sign or a billboard lettered in English. Most of his earlier stories, published between 1955 and 1960, include also his initials, “RS”, on the opening or final panel—sometimes both.

In 1957 he was inspired by what he considered his favorite U.S. story, Mickey Mouse in the World of Tomorrow (1944), to produce Topolino e la nave del microcosmo (“Mickey Mouse and the Microcosm Ship”), which appeared in Topolino no. 167. In this story Mickey and Eega Beeva travel on a spaceship strongly reminiscent of those used by Brick Bradford for his voyages through atoms and time. In the same year he came out with his own version of the Flying Dutchman legend—only this time with a Flying Scotsman—a theme to be picked up only a couple of years later by Carl Barks in one of his great Uncle Scrooge stories (Uncle $crooge no. 25, March-May 1959; completed by Barks in April 1958). Scarpa’s Ducks owe much to Carl Barks’. As the Venetian author pointed out:

What has always fascinated me about Barks’ stories is how he built them up and how he developed the different characters’ personalities—not only Donald Duck’s, which he greatly enriched. In Barks’ stories it was the whole approach that was different compared with Donald’s older, shorter adventures.3

Another Scarpa masterpiece appeared in Topolino issues 183–184 (1958), Topolino e l’unghia di Kalì (“Mickey Mouse and Kali’s Nail”), a thriller in the best traditions of Agatha Christie. Here Scarpa made much use of grey tones, thereby emphasizing the illusion that the story was a newspaper continuity.

However, he probably reached the pinnacle of his art with his 1959 story Topolino e la Dimensione Delta (“Mickey Mouse and the Delta Dimension”), which ran in issues 206–207 of Topolino. For this adventure he revived Dr. Einmug (known in Italy as Dottor Enigm), the atomic scientist who had first appeared in Floyd Gottfredson’s Mickey Mouse on Sky Island (1936–37). Scarpa introduced a character of his own in this tale, an enlarged and humanized atom called Atomino Bip-Bip, created by Einmug and endowed with extraordinary powers. Atomino eventually became a regular guest star in Topolino’s pages.

Scarpa was much more than just another cartoonist. In 1961 he wrote an drew a story called Paperino e il colosso del Nilo (“Donald Duck and the Colossus of the Nile”), which appeared in Topolino issues 292–293. In this story Uncle Scrooge, interested in a uranium deposit located under gigantic Egyptian monuments, decides to cut the statues into numbered blocks; he has these transported to a plateau and reconstructed so that the monuments are exactly as they were before. This very technique was used in 1966–67 to preserve the ancient temple of Abu Simbel when the area behind the Aswan High Dam was flooded.4

Scarpa drew and often wrote hundreds of stories featuring the Disney characters, creating some important ones himself. Among these we can note Trudy, Pete’s partner in life and crime, who made her debut in Topolino e la collana Chirikawa (“Mickey Mouse and the Chirikawa Necklace”, 1960), a great story in which Scarpa paid homage to one of his favorite movie directors, Alfred Hitchcock, drawing inspiration from Spellbound (1945) and Vertigo (1958) for the scenes in which a hypnotized Mickey relives a shocking episode in his childhood. In 1977, Scarpa would give Pete and Trudy an accomplice—a cat criminal scientist called Plottigat, who happened to be Pete’s cousin. As regards Duck stories, Brigitta MacBridge (whose blonde hair is heart-shaped) was first seen in Zio Paperone e l’ultimo Balabù (“Uncle Scrooge and The Last Balaboo,” 1960), and since then she has used every conceivable ruse to ensnare old Scrooge in matrimony.

Continued in "Disney Comics"!

About Theme Park Press

Theme Park Press is the world's leading independent publisher of books about the Disney company, its history, its films and animation, and its theme parks. We make the happiest books on earth!

Our catalog includes guidebooks, memoirs, fiction, popular history, scholarly works, family favorites, and many other titles written by Disney Legends, Disney animators and artists, Mouseketeers, Cast Members, historians, academics, executives, prominent bloggers, and talented first-time authors.

We love chatting about what we do: drop us a line, any time.

Theme Park Press Books

The Unauthorized Story of Walt Disney's Haunted Mansion The Ride Delegate 501 Ways to Make the Most of Your Walt Disney World Vacation The Cotton Candy Road Trip The Wonderful World of Customer Service at Disney Disney Destinies Disney Melodies The Happiest Workplace on Earth Storm over the Bay A Historical Tour of Walt Disney World: Volume 1 Mouse in Transition Mouseketeers Down Under Murder in the Magic Kingdom Walt Disney and the Promise of Progress City Service with Character Son of Faster Cheaper A Tale of Two Resorts I Saw Ariel Do a Keg Stand The Adventures of Young Walt Disney Death in the Tragic Kingdom Two Girls and a Mouse Tale Ears & Bubbles The Easy Guide 2015 Who's the Leader of the Club? Disney's Hollywood Studios Funny Animals Life in the Mouse House The Book of Mouse Disney's Grand Tour The Accidental Mouseketeer The Vault of Walt: Volume 1 The Vault of Walt: Volume 2 The Vault of Walt: Volume 3 Who's Afraid of the Song of the South? Amber Earns Her Ears Ema Earns Her Ears Sara Earns Her Ears Katie Earns Her Ears Brittany Earns Her Ears Walt's People: Volume 1 Walt's People: Volume 2 Walt's People: Volume 13 Walt's People: Volume 14 Walt's People: Volume 15

Write for Theme Park Press

We're always in the market for new authors with great ideas. Or great authors with new ideas. Whichever type of author you are, we'd be happy to discuss your book. Before you contact us, however, please make sure you can answer "yes" to these threshold questions:

Is It Right for Us?

We specialize in books that have some connection to Disney or theme parks. Disney, of course, has become a broad topic, and encompasses not just theme parks and films but comic books, animation, and a big chunk of pop culture. Your book should fit into one (or more) of those broad categories.

Is It Going to Make Money?

There's never a guarantee that any book will make money, but certain types of books are less likely to do so than others. They include: hardcovers, books with color photos, and books that go on forever ("forever" as in 400+ pages). We won't automatically turn down these types of books, but you'll have to be a really good salesman to convince us.

Are You Great to Work With?

Writing books and publishing books should be fun. The last thing you want, and the last thing we want, is a contentious relationship. We work with authors who share our philosophy of no drama and zero attitude, and the desire for a respectful, realistic, mutually beneficial partnership.

If you said "yes" three times, please step inside.