- Visit the Imagineering Graveyard

- Now Sailing: "Skipper Stories" - Tales from the Jungle Cruise

- Coming Soon: The biography of Disney animator Jack Hannah

- Coming Soon: A Haunted Mansion anthology

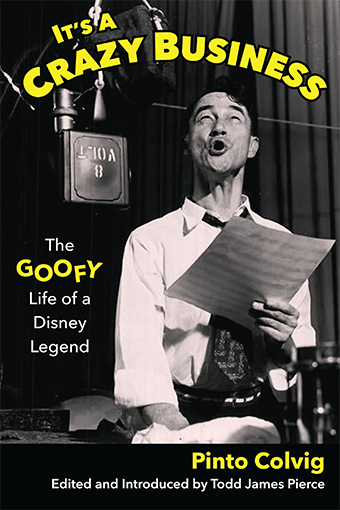

It's a Crazy Business

The Goofy Life of a Disney Legend

by Pinto Colvig | Release Date: July 17, 2015 | Availability: Print, Kindle

The Goofy Life of a Disney Legend

Disney Legend Pinto Colvig, best known as the voice of Goofy, wrote a book in the 1940s primarily about his years working for Walt at the Disney Studio. The book was packed away and forgotten, until now. You've never read anything like it.

Pinto writes in character, elevating his book from mere journal to an important piece of Americana, and allowing him to evoke long-gone people and places with astonishing immediacy. You'll follow him from rural Oregon to Hollywood and the Disney Studio and finally to an institution as he recovers from a nervous breakdown brought on by his vocalization of Grumpy the Dwarf.

It's a Crazy Business includes:

- Pinto's early adventures in Hollywood, writing gags for Mack Sennett and voicing a Munchkin in The Wizard of Oz

- Pinto's arrival at the Disney Studio in the early 1930s, where he worked on gags for Walt and voiced Goofy, Grumpy, and the Practical Pig

- Pinto's vivid recollections of story meetings with Walt and the often eccentric behaviors of early Disney artists and gagmen

- Pinto's nervous breakdown and confinement in the "nut hatch", with surreal fantasies of skeletal Dwarfs and a bedside chat with God

The life of a comedic genius: in his own gag-strewn words!

Table of Contents

Introduction: Pinto Colvig—The Early Years

Author's Note

Chapter 1: Call Me Crazy

Chapter 2: My Life as a Dog

Chapter 3: How I Came to Hollywood

Chapter 4: The Pioneer Days of Sound

Chapter 5: The Foley Game

Chapter 6: I Come to the Disney Studio

Chapter 7: The Disney Gagmen

Chapter 8: The Disney Story Meeting

Chapter 9: Music and Humor at Disney's

Chapter 10: Where Stories Come From

Chapter 11: The VIP Treatment at Disney's

Chapter 12: Improvements

Chapter 13: The Disney Voice Actors

Chapter 14: Early Experiences

Chapter 15: Walt Disney and Snow White

Chapter 16: Studio Work Takes Its Toll

Chapter 17: Paging Mr. Psychiatrist

Notes

Introduction: Pinto Colvig—The Early Years

He was born Vance DeBar Colvig, but because of his freckles he earned the nickname “Pinto”, meaning spotted. It was a name he would later use as a performer, a name that better expressed his carefree sense of humor, his unconventional lifestyle, his ambitions as a cartoonist. Once, in a letter to a friend, he described his early life as being filled with “wild and checkered” experiences. He was a hobo, a circus clown, a vaudeville performer, a boy who—like Walt Disney—never graduated from high school, yet left an enduring mark on the world of animation. He was the youngest of seven children and, even as a boy, yearned for attention. In this way, Pinto was indeed spotted inside and out.

As an adult, he operated his own animation studio; he was one of the original Keystone Cops; he was a gag writer and actor for early Mack Sennett films, such as those starring Harold Lloyd; he worked with Walter Lantz on early sound cartoons, but his most enduring legacy involves his work for Disney. Pinto joined the Disney studio in 1930, back when it was a small collection of buildings on Hyperion Avenue. There, he worked as a storyman, a gagman, a lyricist, and a voice artist. He provided the original voice of Goofy and invented the various woofs that would form Pluto’s canine language. He voiced two, maybe three Dwarfs in Snow White: he provided voices for Grumpy and Sleepy as well as hiccups for Dopey, the dwarf who didn’t speak. He gruffed out the voice for one of the three little pigs (Practical Pig) and corned up the grasshopper in The Grasshopper and the Ants. From 1935 until 1937, he worked under an exclusive contract for Disney and only separated from the studio because he believed he could earn more money elsewhere. Unlike animators and background painters, Pinto’s work wasn’t exclusively tied to animation. He could create voices and sound effects for radio; he could develop scripts; he could compose songs. He was a man of many talents.

After leaving his exclusive contract, he worked for the Fleischer animation studio, Paramount, and also created the character of Bozo the Clown for Capitol Records. But from 1941 until the end of his life, he returned to Disney on a project-by-project basis, primarily to voice Goofy and to help promote films. His last recording session for Disney was finished on June 2, 1967, for an episode of The Wonderful World of Disney called “How the West was Lost”.

Four months later he died.

This memoir, It’s a Crazy Business, was written in the early 1940s, while Pinto’s youthful experience at Disney’s and other studios was still fresh in his mind. The 1940s brought a type of early fame to Pinto. While he worked for the Fleischer animation studio, the Miami Herald featured a two-page, eight-photo spread of him mugging various comic emotions for the camera. He was profiled in Radio Life, Coronet, and American Magazine. He appeared in Talk of the Town. For weeks, in 1944, to promote a re-release of Snow White, he toured the country with Adriana Caselotti, the voice of Snow White. Together they played large theaters, school auditoriums, and army camps to support the troops, where thousands crowded in to see them. Through these articles and appearances, Pinto came to understand the public’s interest in the Disney studio, in animation, even in himself.

Pinto’s memoir is mostly concerned with his early career in Hollywood, from the Mack Sennett silent, black-and-white comedies to Disney’s first feature-length cartoon, as movies transformed themselves, adding length, color, and sound. But Pinto’s life didn’t simply encapsulate the early transformation of Hollywood. His life story illustrates the revolution of American entertainment in the twentieth century, from neighborhood bands and corner vaudeville theaters to international triumphs of cinema. In a way, the lens of Pinto’s memoir isn’t quite wide enough. It only captures part of this great American picture. To understand the rest of it—how one man could be cartoonist, animator, voice actor, gagman, lyricist, sound effects man, and radio personality, you first need to know a few things about Pinto’s early years, that strange soup of boyhood experiences that eventually formed the man who gave his voice to the cartoons, who watched Hollywood grow up and fill theaters around the world with films he helped create.

Jacksonville, Oregon, a gold-rush town, surrounded by open hills wooded with sugar pine, laurel and oak. It was filled with pioneers and their children, such as the Colvigs, a town with a playhouse, a single row of shops, a blacksmith, a gristmill, and a few restaurants. It was also the town where, in 1892, Pinto was born. He grew up in a musical family and as such learned to play the clarinet at a young age. On holidays, he marched with the town’s Silver Cornet band. In the evenings, sometimes, he would sneak down to the local bar—a place his mother called Al’s “Den of Iniquity”—as Al owned the only phonograph in town. Out back, behind the joint, Pinto would listen to the scratch and hiss of those early records, “Won’t You Come Home, Bill Baily” and “Said the Saucy Little Bird on Nellie’s Hat”, then he’d rush home to write down the lyrics before he forgot them.

Music formed the culture of Pinto’s early life, a culture that he carried to school and also to the playhouse in town. But unlike the other young musicians, Pinto learned that he could make people laugh with music, squeaking out notes with comic precision and forcing his gaze cross-eyed. Often he punctuated his performance with a humorous expression of surprise. He was a vaudeville musician, already understanding comedy touched his soul more deeply than music. About this, Pinto would later comment: “I guess I was just meant to be a clown.”

About once a year a circus came to Medford, just down the road from Pinto’s hometown. “Us kids would collect ‘gunny sacks’ and beer bottles and whisky flasks for weeks to get enough money to go,” Pinto remembers. After each trip to the big top, he thought about the circus for weeks. In particular, he was fascinated with the clowns and other types of performers, much to the irritation of his father, a local attorney who’d earned the nickname “The Judge”. He often talked about becoming a clown, and at the age of twelve, he literally got the chance.

His big break came in 1905 when his father took him to Portland to visit the Lewis & Clark Centennial Expo. The Expo featured pavilions from twenty-one countries and sixteen states, as well as blimp rides, free motion picture exhibitions (a novelty in 1905), and amusement park fare. But Pinto was enchanted with one exhibit on the midway, the Temple of Mirth, which he knew by its nickname, the Crazy House. It was described in one newspaper as “the funniest thing you ever saw…[with curved mirrors that present a person’s reflection] in a thousand distorted views.” Outside the Crazy House was a carnival barker dressed as a clown, beating a drum and huckstering people over with his comic sales talk. “Portland used to have a well-known clown back in those days. His name was Habba Habba and he had a ring in his nose like a cannibal.” After taking a look at the entertainment, Pinto thought he might find a place for himself inside this beautiful ruckus. “I went up to him and said I had a clarinet and when I hit the high notes I couldn’t help looking cross-eyed.”

“OK,” Habba Habba told him. “Come back tomorrow.”

But Pinto, eager to join the midway, collected his clarinet from his father’s hotel room and returned that same day, where he squawked out a few funny notes. After considering Pinto’s performance, a smile appeared on Habba Habba’s face.

“The next day the guy put the clown white on me for the first time. Then he made me put on an old derby, and some big old clothes.” With this, Pinto was transformed into a twelve-year-old tramp-clown. The barker gave his approval and out on the midway he went.

For days, Pinto had the run of the place: rides, exhibits, and even the girlie shows. Because he was good with the pen, he became friends with the man who ran the Egypt pavilion, where he was asked to help with the man’s love letters to one of the dancers because he couldn’t read or write. “I still remember her name,” Pinto told a reporter years later, “Corina. I used to add a little to the letters I read him.”

For each letter he wrote, the man paid Pinto a handful of cigarettes and a few complimentary camel rides.

“Then she’d write letters back, and he’d call [to me], ‘Hey, keed, I got a letter from Corina. You read.’ Then I’d get more cigarettes and camel rides.”

But for Pinto, the carnival events didn’t remain in Portland. Back home in Jacksonville—most likely after his big adventure with the Expo—he started his own backyard all-kid circus. “At one time we had a willow whistle band with Pinto Colvig as conductor,” his childhood friend George Wendt recalled. “[Also] trained dogs, trapeze, snake man, magician…As I remember, the admission was two sticks of gum or 10 marbles.”

When Pinto was thirteen his family moved from rural Jacksonville to the nearby railway town of Medford, where brass bands and circuses continued to perform a few times each year. For the bands, Pinto volunteered to carry banners or hold music as they performed through town, and he never missed a circus performance, especially as they rekindled his memories of working alongside a clown barker in Portland. At school, he was drawn to art, particularly the type of cartooning that appeared in papers. He learned what he could in Medford, and he studied the funny pages, believing he might teach himself how to draw. “I thought it would be mighty nice to find myself on the twenty-fifth floor of The New York Times Building wearing an artist’s purple smock.”

School, however, was never Pinto’s strong suit. He attended elementary school and, up through the age of 15, attended junior high as well. According to local records, he appears to have finished the eighth grade, though did not pass his exit exams. He took them once, on May 14, 1908, receiving high scores in Writing and Reading but low scores in Civil Government and Grammar. He signed up to re-take the exams on June 11, but apparently never did.

Two years later, at the age of seventeen, he joined his brother in Portland, where he focused on cartooning. He entered contests and even won a weekly prize given out by Judge magazine. He hoped to formally pursue drawing in the fall with a class taught by political cartoonist Homer Davenport. But his father, the Judge, looked down on many of Pinto’s antics. “My future,” Pinto once explained, “was a serious matter with Dad. He wanted me to become a great lawyer or a great baseball player.” But after long discussions, Pinto agreed to come home from Portland, put off his interest in cartooning, and take an evening job at the Medford train depot. He would soon turn eighteen years old, and he bristled at the prospect of dull, adult responsibility.

One of his jobs was to check every car on the sidetracks and enter it into a log. But this type of tedious work simply couldn’t hold Pinto’s interest. “One evening, with time to waste,” he once told a reporter, “I made the entry by drawing a picture of the [train] car, putting a hobo on top of it with a brakeman kicking him off.” A week later, his boss complained, telling Pinto that he “was working for a railroad, not a comic supplement in a newspaper” then pointing out that he should know the difference.

Pinto objected to the way the man talked about his drawing. Likely using this moment to leave a dull job, Pinto ended the disagreement by simply quitting.

After the depot, Pinto briefly took a job with York’s concert band—a traveling outfit that soon folded, leaving him broke once again, riding with an impoverished freedom as “the tramp cartoonist” on top of boxcars. From there he traveled to Corvallis, Oregon, where his brother and some of his childhood friends were attending Oregon Agricultural College (now Oregon State University). Pinto’s plans didn’t necessarily include college, though this, of course, was what his father wanted. As he would later explain: “[I] landed in Corvallis October 10, 1910 (10-10-10), where I met a lot of my hometown Medford guys. I was on my way to San Francisco to join a band en route to Australia; but when Cap’ Beard learned that I played E-flat clarinet, he encouraged me to sign up for a course in [the] art department so I could play in the band… OAC had a good band in those days. About 60 pieces. No girls! No slick chick drum majorettes! Dammit! But we had fun—especially on tours to Roseburg Strawberry Festival each spring. On weekends (weather permitting) I’d get the urge and take off on hobo trips; returning Monday a.m. in time for first period.”

As he did not have a high school education, he was admitted to OAC as a “special student”. To friends, later in life, he would make many jokes about college. To some, he claimed that in college he primarily learned to roll his own cigarettes and row a canoe. For his college alumni magazine, he joked that he “majored in campustry and canoe-ology!” But clearly Pinto loved some of his studies at college. He enjoyed ancient history taught by “dear old ‘Jackie’ Horner”, a man Pinto would later describe as “an interesting and likable character”, even though Pinto knew so little that for one exam he simply drew “cartoons of famous old Greeks and Romans”. He loved band. He also loved art, especially as the college allowed him to pursue his interest in cartooning.

In college, Pinto studied drawing and illustration and worked toward becoming a commercial cartoonist. Outside of his classes, he developed skills as a caricaturist and even put together his own “chalk-talk routine”. In the early part of the twentieth century, a chalk-talk routine was a vaudeville act where an artist created drawings for his audience while delivering jokes or laying down a funny story. For this act—likely first delivered on the OAC campus sometime in the autumn of 1912—he billed himself as “Pinto, the Nightmare of Caricature”.

According to the campus paper, Pinto created quick and amazing drawings using nothing more than “mustache blacking and graphite—so he said”. For fifteen or twenty minutes, he captivated the audience by producing humorous drawings of professors and students. The high point of his act was the magical, changing drawing. He would draw one object—such as a wine glass—and then with “a half-dozen strokes made this [wine glass into] a long-nosed greenhorn, new to Oregon, who was sucking cider through a straw. Colvig is a hummer,” the college paper concluded, “with real ability, and his stunt will prove tremendously popular anywhere.”

That December, over Christmas recess, Pinto toured Oregon with the college band, and the musical director allowed him to perform his “nightmare” caricature routine as part of the show. In Medford, the paper explained that his routine kept the audience in “an uproar for 15 minutes”. A little farther south, in Ashland, the paper confirmed that “he is certainly gifted, both as a cartoonist and as a comedian”. The personal lesson for Pinto, however, was larger: he was learning that his humorous, artistic abilities might have value out in the real world.

He was in college for three years, more or less, before wanderlust struck him again in a big way. College was, by far, the longest of his youthful endeavors, with the shadow of his father most likely looming large over his studies. When he first arrived at OAC, he audited a drawing class to learn basic skills as he had little formal training in art. The following term, he took a drawing class for a grade and received a “C”. For a while his college career went reasonably well. But in the academic year 1912‒1913, he signed up for 12 credits and didn’t finish any of them.

Though he would return to college at least once (as his departure date according to an alumni publication was 1915), he again found his freedom in travel and performance: he went north and delivered his “nightmare” chalk-talk routine to vaudeville audiences on the Pantages circuit. For his act, he billed himself as “the human leopard, wandering minstrel and society tramp”. In ways, this was the perfect act for the young Pinto, an act that would confirm his ability as a humorous artist, one who could also lay down a funny story. His path from college to cartooning might’ve been more direct, except while in Seattle the fanciful notes of a calliope brought him back to the circus once more. After arranging a job in a traveling circus band, Pinto traded in his vaudeville rags for the white gloves and baggy overalls of a clown. He was officially a member of the Al G. Barnes Big 4-Ring Wild Animal Circus.

Later in life, Colvig would present this escapade as “running away with the circus” which wasn’t entirely true. He may have been running away from responsibility or running away from the work-a-day life of an average Joe, maybe even running from the endless exams in college. But he was too old to truly run away with the circus. He simply changed jobs, from one type of performer to another.

The circus tour lasted for three months, covering the upper Midwest and also Canada. When the tour finished, he returned to vaudeville, where he now billed himself as “The Eccentric Cartoonist”.

During his final year (or years) of college, Pinto enjoyed a double life, spending part of the year in Corvallis to complete his education in art (probably to satisfy his parents) and part of it on the road. “Come early springtime,” he later wrote, “elephants and Call-of-the-Calliope would lure me back to the circus, where I clowned, played Big Top and often pinch-hit as ‘barker’ when our big show announcer showed up too stewed to spiel!”

The following summer, after touring the country, Pinto returned home, where he found his father reluctantly proud of him “in spite of the original way which the latter chose to obtain an education”. For a local paper, his father would explain that Pinto “learned more from a circus than he did from college”. That same summer, Pinto received his first full-time job offer as a cartoonist, working for a newspaper in Nevada, the Rockroller. The job only lasted a few months as the paper folded when the publisher took ill. From there, two more summer tours with the circus. And from there, after marriage (to Margaret Slavin of Portland), he made his way to California, where he found work with the Animated Cartoon Film Corporation of San Francisco. Though the Animated Cartoon Film Corp mostly produced ads, this was Pinto’s entry into the movies, the moment, more or less, that begins his memoir.

Pinto’s story is a large one, how a tramp-illustrator-lyricist-clown would help create cartoon characters that would endure far beyond his life. The memoir features Pinto, dozens of animators and directors, and celebrities that would shape popular culture in the early decades of the twentieth century, celebrities such as Jack Benny, Charlie Chaplin, Leopold Stokowski, and of course Walt Disney. Without further delay, then, in Pinto’s own rustic tones, are the years that changed his life and lifted Hollywood from silent one- and two-reel curiosities to classic films that are still screened around the world.

Note: The introduction is annotated with copious footnotes which don't appear here, but do appear in the book.

Pinto Colvig

Pinto Colvig ran off to join the circus as a child and then went on to become a vaudeville actor, radio actor, newspaper cartoonist, and voice performer, known in particular for his iconic portrayals of such Disney characters as Goofy and Grumpy. His autobiography captures his eccentricity and brilliance in a uniquely American tale.

Todd James Pierce

Todd James Pierce is a professor of English at Cal Poly University. He is the author of the novel The Australia Stories (MacAdam/Cage, 2003) and the story collection Newsworld (University of Pittsburgh Press, 2006), which won the Drue Heinz Literature Prize and was a finalist for the John Gardner Book Award and the Paterson Prize. His work has been published in over 75 magazines and journals, including Fiction, The Georgia Review, The Gettysburg Review, Harvard Review, Indiana Review, North American Review, Shenandoah, and The Sun.

Pinto pulls back the curtain on what goes on during the infamous Disney story meetings.

There is no sadder scene than to peek in on a group of gagmen in the throes of bearing down on a comedy situation. A morose and worried lot. One would believe that each of them had just received a message that his home had burned or some other such calamity.

Now and then, in the quietude of meditation, one of them will suddenly leap to his feet, snap his fingers, and with a spurt of smiling enthusiasm, blurt out some asinine line of meaningless chatter, only to be followed by what Robert Service so wonderfully describes as “a silence you most can hear”. These lulls, however, can last only so long. Otherwise, high-pressured brains (if any present) might snap and go berserk. These pressure-lulls are usually broken and eased by one of the “side trackers” telling an off-color story or an incident in his life that has nothing to do with the story in question. That’s the spot where a Koster-in-the-Can-in-the-Kiester narrative or an “Otto-type” will tell about a lecture he had attended pertaining to The Inter-changeable Sex Life of the Carnivorus Hyaenidae. (Hyena to you!)

These “side-tracking” recesses are sometimes bombshelled by an abrupt exclamation from one of the group, “Heads up, gang, here comes Walt!”

Then, a general jabbering from all, enhanced by a commotion of counterfeit enthusiasm with a lot of wild, impromptu flashes such as, “How about having Pluto swallow an alarm clock?”

“Naw,” cuts in another, jumping up, laughing, “Make it a magnet—ploossh! He swallers it!”

“Yeah!” cuts in another. “An’ everything metallic that Pluto runs past zooms and bongs him on th’ fanny!” All laugh loud—all but one. He’s the serious, frowning, non-enthusiastic, deadpan, wet blanket, meditationist (all right—it’s ME) who monosyllables dryly, “How yuh gonna get it outta Pluto’s stummick?”

Silence…and wilting looks.

Walt’s left eyebrow crooks its usual thoughtful droop—his lower jaw drops. Men with blank expressions gape out the window or bury their heads in their arms.

Soon the silence is broken when one of them jumps to his feet, snaps his fingers, and shouts, “I GOT IT!” Everyone comes to life expectantly. His face wilts. “Nope!” he mumbles. “It won’t do.” He flops dejectedly into his chair.

“Out with it!” bawls Walt. “How in hell we gonna get anywhere if you guys keep your thoughts a secret? We’re not mind readers!”

“Aw, it wasn’t anything,” says the dejected one. “Anyway, we did it in Playful Pluto on the spotlight gag.”

“Did what?” Walt demands impatiently.

“Aw, th’ hiccups,” he answers with a taste-of-nastymedicine expression.

Silence and more mournful meditation.

Then Walt’s voice. “Y’know, that hiccups gag reminds me of one time over in France. My buddy and I had leave-of-absence and went to Paris for the weekend. We were taking in the sights and became separated. The damn fool met up with a strange French babe at the carnival grounds; she put a Mickey Finn in his highball, took him up in the world’s largest Ferris wheel at closing time, pinched his wallet, and had her real boyfriend (the Ferris wheel operator) let her out. Then they strapped him in his seat and left for the night. At daybreak my buddy woke up alone, 110 feet above the ground in a drizzly rain, with not only a hangover, but with no money. He had to wait up there until noon when the carnival opened and enough steam brewed in the boiler to bring him back down to earth. The dame wasn’t anywhere around and the French Ferris wheel operator “no-spikka-ze-Eenglish”, so with nothing else that he could do about it, he went back to headquarters, a sadder but wiser soldier.”

“Well, what in hell’s that got to do with th’ hiccups!” challenges one of the group.

“Well, nothing,” returns Walt. “But, y’know,” he brightens, “there might be a thought there…why can’t we have…Mickey get mixed up—”

“Brrrrr-r-r-r-r-ring!” The telephone.

“For you, Walt.”

It’s Dolores, Walt’s secretary. Silence. Walt bangs down the receiver. “Dammit!” he burns. “I’ve got to go back to the office…and just when we were getting hot on an idea, too. Okay, fellas, go ahead an’ see what you can do with it. Or, maybe we could get something funny with Goofy and the Duck out fishing… Anyway, I’ll see you all in the morning.”

Continued in "It's a Crazy Business"!

Pinto explains how some of the Seven Dwarfs in Snow White got their names.

During discussions at story meetings, a great deal of stress was put on the question of characterization—particularly of the dwarfs. Unlike the cartoons of old, we didn’t want just another cycle-group of figures running around in unison. Therefore, it was agreed that each dwarf must have an individual personality all his own; we listed a group of names that obviously would suggest the personality of each one of the dwarf characters. In this, we felt that the group needed a comedy leader, or learned man, so the name “Doc” seemed to fill the bill. “Happy” and “Bashful” were names that came easily. Walt, lover of pantomime that he is, suggested “Dopey” and he analyzed and explained what this character should be—a cute, lovable, dumb little punk, younger than the rest and always getting in Dutch. A sort of composite of Stan Laurel, El Brendel, and Harry Langdon. A sympathetic comic. Walt’s judgment was right and, from the start, we all had the feeling that Dopey would eventually “steal” the picture. And there is no doubt that he did. In fact, we played the situations and gags right into his lap while we were constructing the story.

“Sleepy” was another name that seemed suitable for a character. The one who occasionally wakes up and always says the right thing at the right time. I was chosen to do this voice and model for Sleepy. I guess it is because in real life I fit the character perfectly—the sleepy part, but not the “saying the right thing at the right time”!

Now there were two names to go. “Deafy” was suggested, but later turned down because it might offend those so afflicted.

For once, during the meeting I got a bright idea. I love old men characters of all kinds and in my boyhood at Jacksonville I hob-nobbed around with a bunch of grand old cronies and G.A.R. Civil War veterans—played horseshoes with them, bummed them for chewing tobacco, and entered into many of their whittlin’ contests. Jacksonville had a wide assortment of old codgers of every description—rich, poor, bewhiskered, sideburned, tall, fat, weasened, and bent.

While I was particularly fond of the laughable, happy type, I also got a kick out of the harmless old fussbudget type—those stubborn, cranky old hellraisers who always oppose everything that is said and done. Indeed, the kind who are always writing letters to local newspaper editors and signing them “A. Taxpayer”.

It was natural, then, for me to suggest, for the sake of contrast to the other dwarfs, the name “Grouchy”. I went into character and imitated an old man of my boyhood acquaintance named Stoten Stonewall. How he would gesticulate and fight for his rights at the weekly horseshoe tournaments, or how, when he’d catch us kids smoking behind his barn, he would storm and yell, “Git that cigaroot outta yore mouth, young man! Enny body that’d smoke them god-damn things would suck aigs!” Then he’d squint one eye and speak pointedly to us with his cane, “Look at poor Yock Tatum standin’ over there—fingers all yella, chest all sunk in, lungs all cooked—hmmph! Mark my words, he’ll be deadern a door-nail inside o’ three months…an’ d’ye remember Jim Lowe?” he would further warn. “I seen him on his death bed th’ night he died—yessir!—old Jim Lowe—a-layin’ right there with a cigaroot in his mouth—stark dead!” And while old Stoten was “layin’ down the law” to us, he’d be puffing on an old pipe, one whiff from which would almost kill a mule. When he finished storming, the old gentleman would mosey up to Bum Neuber’s Banquet saloon and drink hot toddies, cuss the Democrats and all wimmin’, and “allow as how th’ whole damn’d country was goin’ to th’ dawgs!” Then he’d mosey back toward home and, if he chanced to meet some of us kids along the way, he was always good for a few Triple-X peppermints that he carried in his vest pocket. His wife just couldn’t stand a man who smelled of booze…and Stoten knew it.

My suggestion was accepted and when I explained further that the character was somewhat on the order of “Grumpy”, a character once played by the English actor Cyril Maude in a play by the same name, Walt brightened.

“Grumpy!” he said. “That’s a better name than Grouchy.” So Grumpy it was.

Now for a name for the remaining dwarf. Many were suggested, but none seemed to fit. Finally, Les Clark, an animator, remembered a man named Wildhack who had worked for Disney’s as a cartoonist, but who in recent years has become proficient as a delineator of snores and sneezes.

“Why not name the seventh dwarf “Sneezy”? suggested Les.

Sneezy! said Walt. “That’s a good name.” Then someone else mentioned that the comic Billy Gilbert also had a “vocabulary” of funny sneezes. So, the name Sneezy was chosen, with Gilbert doing the part.

To watch and hear Bill Gilbert do one of his loud “synthetic” sneezes is one of the funniest things imaginable, but once I saw him actually sneeze legitimately and scarcely anything happened—just a little pfft!

Continued in "It's a Crazy Business"!

About Theme Park Press

Theme Park Press is the world's leading independent publisher of books about the Disney company, its history, its films and animation, and its theme parks. We make the happiest books on earth!

Our catalog includes guidebooks, memoirs, fiction, popular history, scholarly works, family favorites, and many other titles written by Disney Legends, Disney animators and artists, Mouseketeers, Cast Members, historians, academics, executives, prominent bloggers, and talented first-time authors.

We love chatting about what we do: drop us a line, any time.

Theme Park Press Books

The Unauthorized Story of Walt Disney's Haunted Mansion The Ride Delegate 501 Ways to Make the Most of Your Walt Disney World Vacation The Cotton Candy Road Trip The Wonderful World of Customer Service at Disney Disney Destinies Disney Melodies The Happiest Workplace on Earth Storm over the Bay A Historical Tour of Walt Disney World: Volume 1 Mouse in Transition Mouseketeers Down Under Murder in the Magic Kingdom Walt Disney and the Promise of Progress City Service with Character Son of Faster Cheaper A Tale of Two Resorts I Saw Ariel Do a Keg Stand The Adventures of Young Walt Disney Death in the Tragic Kingdom Two Girls and a Mouse Tale Ears & Bubbles The Easy Guide 2015 Who's the Leader of the Club? Disney's Hollywood Studios Funny Animals Life in the Mouse House The Book of Mouse Disney's Grand Tour The Accidental Mouseketeer The Vault of Walt: Volume 1 The Vault of Walt: Volume 2 The Vault of Walt: Volume 3 Who's Afraid of the Song of the South? Amber Earns Her Ears Ema Earns Her Ears Sara Earns Her Ears Katie Earns Her Ears Brittany Earns Her Ears Walt's People: Volume 1 Walt's People: Volume 2 Walt's People: Volume 13 Walt's People: Volume 14 Walt's People: Volume 15

Write for Theme Park Press

We're always in the market for new authors with great ideas. Or great authors with new ideas. Whichever type of author you are, we'd be happy to discuss your book. Before you contact us, however, please make sure you can answer "yes" to these threshold questions:

Is It Right for Us?

We specialize in books that have some connection to Disney or theme parks. Disney, of course, has become a broad topic, and encompasses not just theme parks and films but comic books, animation, and a big chunk of pop culture. Your book should fit into one (or more) of those broad categories.

Is It Going to Make Money?

There's never a guarantee that any book will make money, but certain types of books are less likely to do so than others. They include: hardcovers, books with color photos, and books that go on forever ("forever" as in 400+ pages). We won't automatically turn down these types of books, but you'll have to be a really good salesman to convince us.

Are You Great to Work With?

Writing books and publishing books should be fun. The last thing you want, and the last thing we want, is a contentious relationship. We work with authors who share our philosophy of no drama and zero attitude, and the desire for a respectful, realistic, mutually beneficial partnership.

If you said "yes" three times, please step inside.